When you think about ancient gladiators, you likely have a certain vision that comes to mind: slaves forced to fight to the death for the entertainment of bloodthirsty Romans.

But much of what we think we know about gladiators is actually wrong.

Today on the show, Alexander Mariotti will separate the just-as-fascinating fact from popular-culture-derived fiction when it comes to gladiatorial combat in ancient Rome. Alexander is a historian and an expert on gladiators who’s served as a consultant for shows and films like Spartacus and Gladiator II.

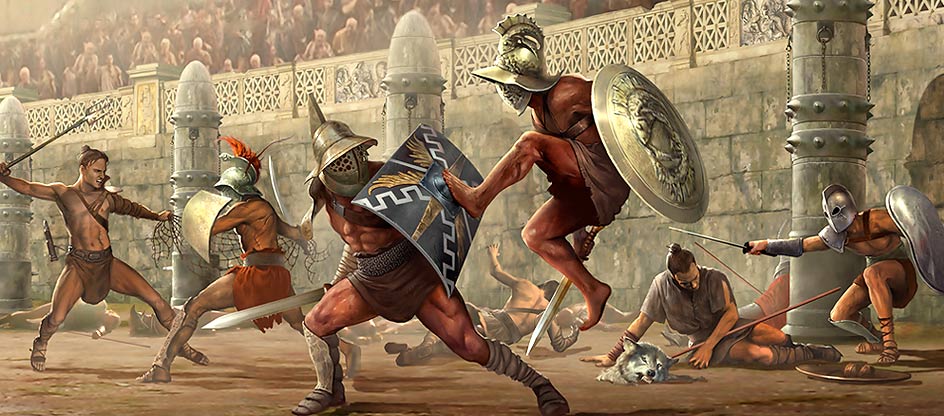

In our conversation, Alexander explains how gladiatorial games evolved from funeral rites into professional sporting events featuring the greatest superstar athletes and sex symbols of the day. We discuss the different types of gladiators, their rigorous training regimens, why gladiators fought in their underwear, and whether they actually fought to the death. Alexander describes what a day at the Colosseum was really like, complete with elaborate special effects, halftime shows, souvenirs, and even concessions. And we talk about the connections between the gladiatorial games and the sports and spectacle culture of today, and why, despite the passage of two millennia, these ancient athletes continue to captivate our imagination.

Resources Related to the Podcast

- AoM Article: Lessons in Manliness from Gladiator

- AoM Article: The Men in the Arena–A Primer on Roman Gladiators

- Gladiator

- Gladiator II

- Spartacus series

- “Gladiator 2 History Consultant Hits Back at Inaccuracy Claims”

Connect With Alexander Mariotti

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of the Art Of Manliness podcast. When you think about ancient gladiators, you likely have a certain vision that comes to mind. Slaves forced to fight to the death for the entertainment of bloodthirsty Romans. But much of what we think we know about gladiators is actually wrong. Today on the show, Alexander Mariotti will separate the just as fascinating fact from popular culture-derived fiction when it comes to gladiatorial combat in ancient Rome. Alexander is a historian and expert on gladiators who served as a consultant for shows and films like Spartacus and Gladiator II. In our conversation, Alexander explains how gladiatorial games evolved from funeral rites to professional sporting events featuring the greatest superstar athletes and sex symbols of the day. We discuss the different types of gladiators, their rigorous training regimens, why gladiators fought in their underwear, and whether they actually fought to the death. Alexander describes what a day at the Coliseum was really like, complete with elaborate special effects, halftime shows, souvenirs, and even concessions. And we talk about the connection between the gladiatorial games and the sports and spectacle culture of today, and why, despite the passage of two millennia, these ancient athletes continue to captivate our imagination. After show is over, check out our show notes at aom.is/gladiators. All right, Alexander Mariotti, welcome to the show.

Alexander Mariotti: Brent, thank you so much for having me. What an immense pleasure.

Brett McKay: So, you are an expert on the history of gladiators and you’ve taken that expertise. You’ve done a lot of research writing about gladiatorial combat in ancient Rome and you’ve served as a history consultant for shows like Rome, Spartacus. You’re there to make sure that the scenes they depict in those historical shows are as accurate as possible. How did you make a career out of researching and consulting about the history of Roman gladiators? Because I’m sure for a lot of guys, this sounds like a dream job.

Alexander Mariotti: It certainly is a dream job. I think it starts with the most important part, which is the lonely childhood. And a lot of time spent alone, thinking about weapons and armor and gladiators and Caesars and all that kind of stuff. And I was very lucky because my parents were immensely into history and I grew up playing in the Coliseum. So the Coliseum for me was just a little place that my brother and I would go hang out and kick a football. There really wasn’t, I think, such a vested interest in the gladiatorial world as there is today. So as I went on and I studied I think it’s just a world that kept calling me back and the more I got into it the more I was fascinated by it and it’s just the complexity of the sport, of its origins, of what it meant was just so immense, that it’s just one of these topics that when you go in, you just go down the sinkhole.

Brett McKay: Well, I hope in this conversation we do today, we can let our listeners know more about ancient gladiatorial combat and dispel a lot of myths because I think we’ll talk about this thanks to popular culture movies in particular there are a lot of myths about how gladiators fought and what it was like to be a gladiator. Let’s start with this basic question. What are the origins of gladiatorial combat? How do they end up with this thing where they built a giant arena so they could watch people fight. What’s the origins of it?

Alexander Mariotti: Well, the interesting thing is that there’s sort of various stages and what’s happened is that it’s an amalgamation of different pieces of historical context put together. So you know, as far as kings and feuding warfare has existed, there’s always been the sense of when there’s a funeral to put on a sort of, or the death of some very important person, to put on a very grandiose funeral. This usually would involve combat or bloodletting or sacrifice. You can go back to the first kings of Egypt. But in the history of gladiatorial combat, it comes from ancient Greece. So the Greeks were quite prone to when great heroes or important people passed, they would have games at the funeral. And I mean, these games involved boxing and javelin throwing and wrestling, but also fighting with weapons. And then you also had sacrifice. So if you take, for example, the Iliad, which is a piece of historical fiction, but it’s got a lot of historical notes in it, Achilles actually does that for Patroclus. He puts on a funeral in Book 23, and he’s got, you know, the soldiers, the Greeks are fighting in combat, but they’re doing it in a sort of sporting way to honor the dead. And he also sacrifices these Trojans.

So that kind of culture mixed in with the Greeks, you know, starting the Olympics, so having professional combat sports, you start to see the sort of very very beginnings, the seeds of gladiatorial combat. And what happens is the Greeks conquered in the 8th century, they start moving towards the south of Italy and colonizing it. So they bring their culture with them. So by the time that the Romans start to become a force of nature, they’re really infused in Greek culture. They’re infused with the culture that when there’s a funeral, they have bloodletting, there’s combat sports that they’ve inherited. And so, slowly but surely, that’s where the sport of gladiatorial combat starts to come from.

Brett McKay: Okay, so the seeds of gladiatorial combat came from the Greek tradition of holding combat games at funerals to honor the dead. And then wealthy Romans adopt this practice. How did these funeral combatants differ and how did things then evolve into the gladiatorial games that we think of when we think of gladiators?

Alexander Mariotti: So you would have these people fight over the funeral, but these aren’t really, I wouldn’t define them gladiators because gladiators are what comes afterwards. They’re athletes, they’re sports figures. These guys are called Bestiarii, which means they come from the bustum, the fire. So they’re the sort of, you know, because obviously you cremated people back then, and these men would fight amongst the fire or alongside the fire. Think of them almost as professional grievers. They’re there to put on a show to spill blood, to honor the dead, and it’s tied into two parts of Roman religion. The first is that the Romans believed as long as someone spoke your name, as long as you’re remembered, you continue to exist. So in putting on a very lavish funeral, you will be remembered because people say, well, I had this great feast at this funeral, but I also saw these incredible examples of combat. The other thing was that they believed that when you died, you became a shadow.

So to allow you to gain enough strength to pass the underworld, you needed blood of someone living. So the spilling of blood, not necessarily death, but just the spilling of blood was enough to go forward. So that’s where it is in Rome, but it takes someone very astute by the name of P. Rutilius Rufus, Publius Rutilius Rufus, and in 105 BC, this guy just obviously has observed how much people reacted to the fights. Because what we see is that initially the funerals were a feast, there was mourning, there was the fighting. The fighting starts to become the most prominent part because they realize that anyone who comes to these events, that’s what they’re really talking about. And Rufus understands this and what he does is he puts on the first gladiator fights, which are purely for sport. And from that moment on, the gladiatorial phenomena really starts to build because it’s a sport of its own. It’s born out of its own and it’s nothing to do with funeral rights and it’s nothing to do with death necessarily. It’s to do with show, with spectacle.

Brett McKay: And when did that happen?

Alexander Mariotti: That’s one of 105 BC. So you’re talking again, 180 years before the Coliseum’s even built, just to show you how much it progressed and how quickly. But another thing about Rufus which is interesting is he tells us just how well-trained these guys are. Because about 30 years previous, Rome had just got its professional army. So before that, the Roman army was a sort of series of people that were conscripted, brought together. They would fight the war and they would disband. So Rome didn’t really have a standing army. This is changed by Julius’s uncle, a man called Gaius Marius. So at the time of Rufus, the army is only 30 years old. And he actually realizes that these guys are so well trained, these athletes, these gladiators, that he goes to gladiator school in Capua and he hires the gladiator trainers to train the army. And from that moment forth, he produces basically super soldiers because any part of the military training from that point on is actually influenced by gladiatorial training. That’s how well trained these guys were in 105 BC.

Brett McKay: Okay. So brief recap there. Gladiator game started off as a funeral rite and then it shifted to just the fight itself. They became just public spectacle. It was basically like an MMA fight today.

Alexander Mariotti: It’s exactly, well, an MMA fight today is gladiatorial combat. It just doesn’t have the weapons. We’re not there yet. I’m sure in a couple of years, someone will say, why don’t we put weapons with these guys? And what a great idea. And then we’ll have come full circle to the Romans. But I mean, the fact that MMA exists speaks to sort of just how much we are like the Romans. We shouldn’t be surprised at this. Human nature hasn’t changed profoundly in the last 2,000 years. The desires that man holds, whether to be successful, to be remembered, to be loved, to be powerful, these are sort of universal themes that repeat themselves because ultimately people repeat themselves. And so it shouldn’t be surprising that in our culture, despite how civilized we think we are, we still find that one of the biggest sports in the world involves two men in front of, you know, 80,000 people in an arena, you know, beating each other out to see who’s the most primally powerful.

Brett McKay: What role did gladiatorial games play in Roman social and political life?

Alexander Mariotti: Oh, they played an immense part. Actually, that’s one of the things that fascinates me so much about the gladiatorial phenomena is that it was responsible for the Roman Empire. I don’t think you would have had the Principate the emperorship without gladiators because when you look at the Emperor and you look at the poorest in Rome, you know, most people did not live like the 1%. So what does the 1% have in common with the 99%? Well, they have nothing in common because the emperor lives in a palace. He has immense wealth. He eats what he wants. He drinks what he wants. Nothing is close to him. That’s not the reality of most people in ancient Rome. But what did they have in common? Well, what they had in common is that periodically they would meet in an arena and they would watch this sport. And that’s how the emperor won the people because he built the Coliseum. He built an immense stadium and he gives you tickets to come.

And for a brief moment of your life, that hardship that you live, you get to forget it. You get food, you get wine, you get games, you get beast hunts, you get gladiator fights, you get ship battles in the coliseum and all because of this very gracious and you know generous figure and so you love the emperor and exchange he rules. And that’s really not a relationship that’s that different from today, because, you know, if you take the NFL or any sort of sporting body, they do the same thing. They build the stadiums, they put on the shows, and in exchange, they ask you to buy a product. In ancient Rome, the product was the emperor’s power. Today it’s some sort of product placement, but it’s the same relationship we have with our sports today.

Brett McKay: And what’s interesting too, I did some reading in preparation for this, is that even the emperors who weren’t really fond of the gladiatorial games they just, they added a version to it. Like Marcus Aurelius, for example, he wasn’t keen on them. He put limits on the gladiatorial games, but he still put them on because I guess he thought it was just something he had to do to maintain his power.

Alexander Mariotti: Oh yeah, it’s part of it. You know, the power of celebrity is something that’s universal. You see it today whenever, you know, we recently had elections and you see how celebrities roll out for their candidate and they use their sway and their popularity for a cause. Well, you know, it wasn’t that different if you had the top gladiators saying that you were the best Emperor and what a kind guy and out comes a champion gladiator and the Emperor lavishes him with gifts and he says what a great Emperor we have. Well, it’s the same concept really.

Brett McKay: And it seems like there’s also, even at the peak of gladiatorial combat in the Empire, in the Roman Empire, there were a lot of criticisms of it. You could find criticisms, just as you’d find criticisms today of MMA fights.

Alexander Mariotti: Oh, absolutely. There’s an interesting notion, which is that great Roman philosophers complained more, not so much about the sport. I mean, the sport was seen as a very vulgar sport by the great minds. I mean, Marcus thought it was a vulgar sport. He loved wrestling. He thought wrestling was a very noble sport. He didn’t think gladiatorial combat was. But it was more about the effect that it had on the people. That’s the interesting part because they’re more concerned that these games bring out the brutal side of man. And the Romans, just like the Greeks, had a great philosophy about man being in constant battle with his urges. So you see things like the centaur or the story of the hydro with Hercules. They’re really metaphors for man being half beast, half divine and in a constant battle to fight your urges. So you really should try and become more divine. But the games brought out the beast in you.

And that’s what Christians had a problem with gladiator games. We always think that the gladiator games stopped because the Christians were so noble and they wanted to save the lives of gladiators. Well, the truth is the gladiators weren’t dying. That’s not the problem. The problem is that Christian writers say that the games turn men into beasts. And I don’t think that’s really hard to see if you go to a UFC fight you see what it does to the crowd. If you’re in the crowd it’s not a calm intellectual crowd. It is rowdy bestial pumped up adrenaline testosterone pumped crowd fueled by the games.

Brett McKay: Yeah, Seneca, the famous Roman stoic philosopher, he’s also the the assistant to Nero. He had a lot to say about gladiatorial games. He had a lot of things that you were mentioning there about how it just sort of depraves you and makes you feel less human. He talked about how you felt like less of a man after you watched the gladiatorial games, less human. But then he also at the same time, he’d say like, but it was so hard not to watch because it is.

Alexander Mariotti: Oh, but it is. And isn’t that true though? I mean, it’s funny. There’s a great story by a Christian writer about a friend of his who’s studying in Rome, and he’s dragged by some friends to the Coliseum. And, you know, he’s like, oh, no, he refuses. And then he sits there in the crowd and he covers his eyes with his hands. Then he hears a roar and then he hears a clang and then all of a sudden he pulls his hands back and he peeks a little bit and not before long he’s just there cheering with the others and he says he gets drunk on the Furies. And I think that’s very true if you watch, you know, when we watch these sports, it does bring out a side of us that’s primal, that’s sort of genetically in there. And it’s meant to, I mean, it’s meant to then the purpose of the games is whether it’s MMA or gladiatorial combat, it’s about the toughest. It’s about survival. It’s about an example. And that’s when you reach the philosophical side of gladiatorial combat, which is that they represented to the Romans this great philosophy, which I think would be perfect for a podcast called the Art Of Manliness because the manliness to the Romans was virtus.

And what virtus was was a physical and mental endurance that you basically could survive anything physically and mentally to be the toughest of the tough. And gladiators were that because they were incredibly well trained, they were physically brilliant, they were courageous because they fought in a fight that you could die from. You could die from your injuries. I mean, you weren’t joking around. But you also were a great sign of resilience mentally because in the midst of battle when the referee told you to stop you stopped. That takes great self-control. So we don’t really see the gladiators as such but they are a wonderful example of self-control because they are obedient to their trainers, to the referee, to the emperor, and not to their instinct and their adrenaline. That’s virtus. We don’t have this philosophy spoken of today, but it does exist because we see it in our MMA fighters. We see it in our first responders. That’s manliness to the Romans. That’s virtus.

Brett McKay: I love that. That’s really interesting. Let’s talk about the gladiators themselves. I think the popular idea is that the gladiators were criminals, slaves. Is that true?

Alexander Mariotti: They were, but they were also free men. They were also athletes. They were also hunters. Basically you’ve got to again, look at the period of history, right? What opportunities do you have afforded to you 2000 years ago? So, you know, there’s no public education. So if you aren’t lucky to have an education, how are you going to make your money? How are you going to survive? Well, if you’re physically, you know, in a good shape, you could become a soldier. But again, that’s only opened to the poor by Caesar’s uncle in about 130 BC. So what else could you do? And again, being a soldier, it’s not like you’re going to survive. You might die, but you get three square meals and you get taught trade, but you looking at 16 to 25 years of your life. And though of course you gonna get paid is not lucrative, you’re not gonna get rich. Gladiatorial combat offered you another avenue which is that you train to be a gladiator.

You did a two year stunt as a rookie, which was the time it took to train them. And then after that, you took a five year contract, which stipulated how many fights you did per year, but also how much you’re gonna earn. And what we know from Marcus Aurelius’ time, because he passes some laws, which effectively ended the gladiatorial combat because he took the money out of it, is that these guys were making a fortune, an absolute fortune. You’re talking about anything up to 17, 18, 19 times the annual salary of a soldier in a single fight. So you do one to three fights a year, you’re set. And you know, they didn’t have long careers. Of course they didn’t, just as MMA fighters don’t because it was physically taxing. You are still fighting, you’re still beating each other up and you’re still putting the body through immense stress.

Brett McKay: So the gladiators themselves made that money or did it go to their trainer?

Alexander Mariotti: It was a split. Of course it was a split, but you had in your contract stipulated how much you earned.

Brett McKay: That’s fair. I didn’t know that. I always thought it was just like they were just slaves.

Alexander Mariotti: Well, no, but that’s because the slave part is more interesting. You know, if you made a movie about a guy who was out of work, became a gladiator, made a fortune, bought a villa and retired. I mean, that doesn’t sound like a great movie. You want a guy who’s a general who gets his families massacred by, you know, a corrupt emperor. He’s sold into slavery and he has to fight to win his freedom. That’s a story. And those are the stories we pick, but we also create them because they sound good. But that’s not reality. Gladiators were about a split 50-50 of slaves and of free men because people were drawn to the arena. Who wouldn’t be? I mean, you know, you get to stand in front of 80,000 people cheering your name. The Emperor of Rome cheers your name. Who else can say that? And no wonder people were drawn to become gladiators.

Brett McKay: So what was the social status of a gladiator in Ancient Rome? So it sounds like they’re, I mean, the way you’re describing it sounds like they were a professional athlete today.

Alexander Mariotti: Oh, They were. They were the first superstar athletes of their time. More so than, you know, any time I say that someone on the comments section starts going on about the Olympics. The Olympics did not have the reach. The athletes did not have the careers nor the money that gladiators did. When you look at sports stars today, their rich throughout the world, the wealth that they amass, the popularity they have, the only thing akin to that throughout all of human history is the gladiator. They’re the first superstar athletes. Because when you were known in Rome, you were known in the Roman Empire. 60 million people knew who you were. Your fame did not just extend to the regions, it extended to the entire empire from the north of Scotland to the north of Africa. Now socially, yes, you lost your social rights because the Romans did not see… They were very against people making a spectacle of themselves or showing off. So if you are pimp, an undertaker, an actor, you were declared an infami, so you had no political or social standing.

You’re kind of the lowest of the low. But it did really matter. I don’t think people have a great view of Conor McGregor or any of the MMA stars today socially. They rub shoulders with the bigwigs because of their popularity, but they’re not seen as intellectuals. You certainly wouldn’t imagine an MMA fighter becoming a president or a prime minister. And gladiators were the same, but they didn’t really care because they were absolutely adored. I mean, sexually no one else is more desired in the entire Roman Empire than the gladiator. He is the ultimate sex symbol of ancient times, more than the emperor.

Brett McKay: Okay, so half the gladiators were slaves and then half were freemen who volunteered to become gladiators because, I mean, they just wanted a chance at the lifestyle. They wanted fame and glory. And then with the slaves, it was a way for the owners of the slaves to gain prestige in financial gain through their slaves who were gladiators. ‘Cause if they won in the arena, they would get the fame and glory for that. And it was still a selective process cause the owners they would pick from among their slaves, the best of the best. And then they would train them and manage them. It was kind of like investing in racehorses.

Alexander Mariotti: Yeah, you know, well, the gambit of people who would become gladiators, I mean, you had to be tough, let’s be honest. You have to be physically exempt. You have to be really the sort of physical specimen of perfection because you have to have the body to do it. Not everybody became gladiators. You know this notion that poor slaves were thrown into the arena and told to fight is just utter nonsense. Because you’re talking about a war like society who knew combat, who saw war, who saw carnage. So the shows had to be better than the battlefield. And it’s true because the battlefield was scrappy. It was ugly. The battlefield was not beautiful. It was murder. We sort of sanitized combat for show, because when we watch movies, these great battles with these great moves, it wasn’t. It was people hacking each other like animals. The arena was different. It was skillful. It was elegant. It was craftsmanship. It was people studying each other the same way that, you know, boxing and MMA is not the battlefield. It’s not what war looks like and not, it’s not what a street fight looks like. It is about people who know their craft, who’ve studied. So the gladiators kind of gave people the sort of show that they wouldn’t have seen anywhere else.

Brett McKay: Something else that I’ve read, and you can correct me if I’m wrong on this with the idea that some gladiators are criminals because it gets kind of confused or conflated Because criminals could be sentenced to fight in the arena as a form of capital punishment. This included Christians because Christians were considered criminals. So it was like, we’re going to pit these people against the lion. But that wasn’t gladiatorial combat, right?

Alexander Mariotti: No, no. So there’s three very specific categories, which always get sort of amalgamized into one and, you know, later writers, especially Christian writers, kind of confound things that they’d never seen. They’re, you know, it’s kind of like people studying today, studying me. If I write a book about Napoleon, like a source, like, you know, and me telling you, well, Napoleon looked like this and he did that. I mean, I can hypothesize, but you know, I’m 200 years from Napoleon. And when you’ve got writers, 2, 3, 4, sometimes 500 years after the gladiator games, talking about gladiator games, they don’t know really what they’re talking about. They’re talking about something that’s sort of a whisper that’s kind of come along. So you’ve got beast hunters which were bestiarii or venatores. So you had guys who basically were hunters, professional hunters who fought animals or people who kind of tried their luck and were forced to fight against animals. But gladiators do not fight animals for the simple reason you cannot control an animal.

So when you’ve trained a guy and you’ve spent money feeding him and clothing him and housing him and you know having a doctor on call as gladiators did. And then you put them against the lion, the lion is probably going to destroy your asset. Then you’ve got noxii and noxii are criminals. So at half time show, the half time show involved criminals being executed. Now that’s simply because logistically the Emperor has now the attention of 80,000 people who have come to see him. So here’s a little bit of an interesting part of someone fighting a lion. Excellent. Now I’ve got your attention. Here’s a bit of music, here’s some fire-eaters, and now we’re going to condemn the criminals because I want you guys to know that if you cross the lines, if you defy me and defy my rules, this is the consequences. So it’s public execution. And those people were people thrown into the arena, told to fight to the death or pitted against animals, but they are not gladiators. The gladiators come afterwards in the afternoon and they are again professional athletes who’ve spent two years or more training, who’ve been fed, clothed, skillfully trained and sort of brought up in a social way to get us a following, which is still important today, so that when they perform, you want to see them, but they are nothing to do with the other two categories.

Brett McKay: Okay. That’s interesting. I think that’s a good clarification there. We’re going to take a quick break for a word from our sponsors. And now back to the show. One thing I thought was interesting is that there are different types of gladiators. So you have this section of guys who fought one-on-one, but there was different types, just like there’s different positions in American football, like a linebacker or running back, the same thing with gladiators. Well, what type of gladiators existed?

Alexander Mariotti: Well, I would equate it more to the fact that they were the first mixed martial artists because they’re basically mixed martial artists. You’ve got different styles. Just as today you get the Brazilian jiu-jitsu guys and they fight against, you know, people have a taekwondo background with some grappling skills. What you have is you’ve got different categories of gladiators and they have different fighting styles. And this is predominantly based off the type of armor they have. So basically you get two definitive types of gladiators. You get scutarii and parmularii, which are ones with a large shield called a scutum. It’s about a four foot shield and it’s the one that’s used by the Roman soldiers. The parma is a smaller shield, usually square, sometimes round, and depending on the type of armor, the type of category of gladiator, they’re going to have very specific helmets. And that’s going to change the way they fight. So some of the most famous are, for example, the retiarius. He’s the net man. He’s the only gladiator who didn’t have a helmet. He had only a shoulder guard, and he had a net and a trident, and sometimes a small dagger.

But he’s got no armor whatsoever, except for the shoulder guard called a Galera. So you think that’s fairly unfair because again, any strike, any sort of blow he’s going to get, is going to give him a wound. And he’s going to fight against someone like a Secutor. Secutor’s had very large helmets, looked a bit like a fish, very small eye holes, a fin on the top. He had a mannica, which was basically segmented armor, much like you see in the roman soldiers covering his sword arm he has a large shield called the Scutum and he’s got greaves called ocreas. So very well armored guy against a unarmored guy. Well that’s because the guy without the armor, without the helmet is gonna be very quick very nimble and his fighting style is gonna be sort of jabbing a lot keeping his distance with the trident, swinging the net to confuse him and eventually sort of tires his opponent out and win points. Whereas the Secutor being very heavily armored is gonna be a thicker set guy, more muscular. He’s going to be slower, but more powerful. So he really has to study his moves because he’s got to work on the expenditure of energy. And think how exciting where you do have guys with different skills, different armor, different physiques fighting it out because you, you know, you’ve got your favorites, but you also see the skill of the fighter.

Brett McKay: And something about the armor. Didn’t all gladiators fight bare chested or just had like a toga? Some of them had like they had greaves, but other than that, that was pretty much it.

Alexander Mariotti: Well, it’s an interesting thing. In 174 BC gladiators appear in underwear. Now you can see this in a place called Paestum in the south of Italy, in these beautiful fourth century BC frescoes. So they’re the first images of gladiatorial combat we have in Italy. And they look just like a Greek, I mean, again, they’re a copy of a Greek funeral. So they look just like what you see in the Iliad. But what you see is these guys are in underpants, which is called subligaculum. It was a piece of linen fabric that was sort of tied in a triangular fashion around you, basically like briefs today. And the reason why gladiators are placed in them is because they’re trying to save their lives. So it’s interesting that these guys always fought in their underwear. And the reason why is because if you were a tunic and you got a wound, The wool or the linen, if any of those scraps went into your wound, you had a very high probability of infection and dying. The Romans knew this 2000 years ago. You know that’s one of the major cause in the American Civil War was death by infection because of the wool tunics that kept going into the wounds. So the Romans to mitigate this already know this 2000 years ago and they have gladiators fight basically in their underwear for the entire time to preserve them, to save them, which tells you that the whole thing of a gladiator dying is not what we think it is. It’s nonsense.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I wanna dig more into that myth that they fought to the death. But before we do, let’s talk about the just sort of daily life of a gladiator. So if you became a gladiator, you had to go to a school. It’s like a training camp and you basically spent your life there. What was life like in a gladiator school?

Alexander Mariotti: Well, you know, it was, let’s not joke around. The moment you went into gladiator school and you took the oath, whether you were free man, whether you’re a criminal, whatever you were outside was irrelevant. You became clay to be molded by the lanista and the doctores, the gladiator trainers. So you can expect that their lives are most like professional athletes today. Think of MMA fighters. You are taught combinations, you’re doing physical training to build yourself up, so weight training. So they had a very intense system called the Tetrad system, which was a four-day training program that was invented originally for the professional athletes of the Olympic Games. And so basically the first day you have like a preparatory day. So you do sprints, you do some light weights, you do some jumps. The second day was like the intense training day. So you would have done weights, you would have done combinations, you would have lifted like medicine balls. And I’m talking still ancient Rome, by the way, I know this sounds modern, but this is what the Romans were doing.

The third day was a rest day, which is very important. So you ate a good meal. You might have had a bath. You might have had like a sauna or a steam room, which the Romans had. And then on the fourth day, you did specialized training. So that would have been the day that you would have done weapons training, tried out your combinations, had your trainer do your one-twos against the post. All right. So if I strike you with the left and I come with a shield you’re gonna duck at this point come back with a shield hit. So that’s what would have been their sort of daily, you know, or their week to week. And when they were coming up for a fight, the intensity of the training would increase. And then when they were off season, they would bulk, they would eat, they would train lighter, and they would prepare for the next fight. Exactly like professional athletes today.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that sounds exactly like a professional athlete training. Speaking of their diet, I’ve heard that they ate so much grain that they were called barley men. Is that accurate?

Alexander Mariotti: No, I mean it’s accurate and it’s not accurate. Yes, they were called barley men. They did obviously have a… Look, you’ve got to take people and give them a diet, right? So they’re going to do a lot of weight training. They’re going to do a lot of physical exercise. People have tried to use this politically to say that, you know, gladiators are vegetarians. Nonsense. If you can find a vegetarian heavyweight box of the world, I’d love to meet them. You needed protein, of course. So they had a thing called puls, which is like a barley spelt stew, which would have been the main basis. A little bit like if you imagine for sumo wrestlers, they give them like a big sort of stew to beef them up, right? Because you’re taking someone off the street and you’re like, right, I’m going to make you into gladiator. How do I do that cost effective? But they will have, of course, eaten meat and fish and cheese and pretty much everything.

Brett McKay: Okay. So yeah, these guys, they were professional athletes. And so they were trained like professional athletes.

Alexander Mariotti: Right.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about the arena where they fought. I think the most famous gladiatorial arena is the Colosseum in Rome. But were there other places that they fought in the Roman Empire?

Alexander Mariotti: Oh yeah, I mean there was amphitheaters all around the Roman Empire. It’s why I think we are so Roman today is that, you know, if you go back 3, 400 years ago, there was no stadiums around the world. The stadiums started popping up because of the popularity of baseball in America and cricket in England in the 1800s, end of the 1700s. And so they started building stadiums. But 80,000 spectator stadiums, you know, they only started propping up about 80 years ago. So nowadays you can go anywhere in the world and there are stadiums for all sorts of sports. And that’s very much indicative of the Roman world where you could go to North Africa, you go to Spain, you go to Gaul, Germany, Scotland, and they were amphitheaters of various sizes. The oldest surviving amphitheater dates to 70 BC. It’s found in Pompeii. It’s an incredible place. It’s only a 20,000 spectator stadium, but still not bad for a small town.

But yes, the Coliseum is, you know, it’s the Super Bowl. It’s the place you want to fight at when you’ve, I mean, who wouldn’t? Again, you know, 80 to 80,000 people, some say 50, but I tend to think they were more in the higher region because we don’t have any seating, so we don’t know the exact size. But nevertheless, you know, 55,000 to 85,000 people cheering for you. I mean, what a sensation, what a feeling. Imagine coming out of those undergrounds and a tunnel and someone cheering your name and 85,000 people erupting. And it’s such an intense feeling that people chase it today, you know, and very few of us get to experience it. But imagine what it must’ve felt like 2000 years ago.

Brett McKay: Did it work like how you see in the movie Gladiator where, you know, there were gladiatorial arenas in different parts of the empire, like North Africa. Did you like work your way up until you got to the Coliseum? Is that how it worked?

Alexander Mariotti: You could do, yeah. Or you could do the reverse, which was that once you were kind of a veteran, you know, and you’re kind of a little bit past your date, you could still go fight in the lesser provinces. Just as you see sports stars today, you know, when they kind of hit their heyday, they go to different leagues and maybe a little bit lesser prestigious leagues, but still, you know, your name kind of rang true and was still a draw. So I mean, I could give you a great example, you know, Mike Tyson, you know, we recently saw Mike Tyson fight. Who’s he fighting against? Who cares? It’s Mike Tyson, you know, has he fought in a while? No. Does it matter? No, it’s Mike Tyson. His name is legendary. Imagine applying that to Gladiator. You’re the guy who won the fight in the Coliseum in 97 AD. Okay, that was 20 years ago, but still, you’re in relatively good shape. You can go to North Africa, you’re a little bit overweight, you’re not quite the guy you used to be, you’re not quite as fast, but people still know who you are. They want to see you fight.

Brett McKay: Speaking of the Colosseum, is it true that they filled up the Colosseum with water to do naval battles?

Alexander Mariotti: Yes, absolutely. And that’s in the beginning. And it’s to do with a little piece of Fortuna’s history, which was that the building of the Colosseum incredibly came out of some very bad luck for the Emperor Nero, which was the misfortune of the fire of 64 AD. So natural disaster changed the world politically, socially, and culturally, because the fire made Nero unpopular. It wasn’t his fault, but his political rivals blamed him for it. Four years later, he plunges a knife into his neck. He kills himself. And the next emperor that eventually comes after a year of civil war is a sort of down-to-earth guy called Vespasian of the Flavians. And he says, okay, so the emperorship’s in trouble, how do I win popularity? Well, I’ll tell you what, let me take this a piece of Imperial land. I’m going to build a free cinema, theater, sports stadium all into one out of my own pocket. And I’m going to give you guys free tickets and you’re going to see the greatest show on earth. But where they built it was on an artificial lake that Nero had built. So they drained the lake, but they used the drainage system for the Coliseum.

So in the beginning of the Coliseum when it was first opened there was no underground. There were no lifts, trapdoors and pulley systems, that all comes afterwards as the games get more elaborate. But they did have the drainage system so they could drain it. And they could pull the water from the aqueducts and then dump it into the river and have ships come out and do mock naval battles. But eventually the Coliseum games got so elaborate that they had to build under the sands a series of trapdoors and lifts and pulleys and they moved them to a lake called Nemi because it’s just easier to do.

Brett McKay: The guys who took part in these naval battles, were they your typical gladiator or were they another genre or breed?

Alexander Mariotti: They tend to be criminals. They tend to be criminals because it was, again, particularly dangerous. You’ve got to think of actors and stuntmen, you know? Your actor is the asset. He’s the guy that you just can’t take a risk with, so you use the stuntmen. Kind of the same way you’d use criminals. And in fact, it’s from criminals and from a naval battle that we get one of the most famous misconceptions of gladiators, which is that during the time of the Emperor Claudius, they basically organized a naval battle and these guys, these criminals knew that there was no chance they were going to survive. So at least you got to give a criminal chance and say, look, if you fight, you might win your freedom. But they knew they had no chance. So they shouted to the emperor, hail Caesar, those who are about to die salute you. But they were being facetious. It was almost like saying, well, thanks very much. You know, we’re about to die. Hail to you, great Caesar. You know, what kind of a person are you?

And Claudius finds this funny and he actually retorts or not. And so they take it as a pardon. They take it that the emperor has pardon them and he has to hobble down because he had a medical condition and he has to try and convince them to keep fighting to put on show for the spectators. And that whole line, those who are about to die salute you, was never said by gladiators. It’s never recorded again and actually has nothing to do with gladiators, but it does sound cool and that’s why it’s attached.

Brett McKay: Oh yeah. So that’s a myth. I think there was a famous book about gladiators that had that title. Those who are about to die salute you.

Alexander Mariotti: There’s a series I just worked on last year on Amazon and that’s the title of it. And the joke, my joke is always a terrible joke. It’s a history nerd joke, but my joke is if it’s called those who rarely die, you wouldn’t want to watch it. You’re like, that doesn’t sound particularly good. You know, you want high stakes. You want the fact that your hero might meet death and is courageous enough to go and fight.

Brett McKay: So yeah, this leads to our next myth that I want to hopefully debunk here. Gladiators, did they really fight to the death?

Alexander Mariotti: So gladiators fought very rarely on, I mean, an absolute occasion to the death. But again, it’s an absolute rarity. Death did occur and it wasn’t that the gladiators didn’t accept death. They very freely accepted death that they knew that there was a possibility. In the same way that when MMA fighters go and fight, they know there’s a huge risk of being, you know, you might end your life, you might get life ending or life altering injuries. The gladiators accepted that, but they also accepted that because by the time the gladiator sports start to flourish, you know, Greek sports were close to 900 years old. So, you know, people like boxers, pankration fighters, wrestlers, when you look at how brutal they were in the Olympics, the rules, we have recorded deaths of Olympic fighters, of boxers meeting death, of pankrationists killing each other. We also have a huge amount of severe injuries that these guys sustained. So that was kind of generally accepted in the ancient world and gladiators were no different. They accepted that if they stepped into the arena, they could die. Predominantly gladiators will have died from injuries and from infection.

But one of the greatest doctors, actually the sort of great grandfather of modern medicine, a guy called Galen of Pergamon, he became the doctor of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius. And his writings, by the way, are the basis of modern medicine. We wouldn’t have modern medicine to the degree if it wasn’t for his writings, which still survive today. And he learned from working in a gladiator school. So we know the gladiator schools actually employed doctors. And because we found the gladiator cemetery in Turkey, and we can study the bones, we see that these guys have injuries that have been treated and that they’ve recovered from the injuries including medical amputations. So you see that death is not the purpose of the gladiator. Everything is being done from the way they dress, even their armor. I mean what’s the point of having a helmet that fully encases your head? You don’t see that on the battlefield. That’s really not, you know, imperative having a big can over your head with a couple of grades, sort of holes for your eyes, but it’s to protect the head of the gladiator and make him look cool at the same time. But you don’t see that in the battlefield.

Brett McKay: Yeah. So the goal of these bouts wasn’t to kill each other. It was to put on a good show.

Alexander Mariotti: The purpose was absolutely not death. No, it was to put on a good show. And in fact, there’s historical evidence that they didn’t fight with sharpened weapons. We have an inscription of somebody asking special dispensation from the emperor, an emperor called Alexander Severus, to be able to use sharpened weapons because it was such a risk and because the gladiator sport was monopolized by the Emperor. The Emperor owns the schools and everything. It’s all under the emperorship. So they have to ask permission to have the gladiators fighting using weapons that are sharpened weapons because of the degree of risk. And we know that even Marcus Aurelius makes gladiators fight with wooden weapons because he didn’t like the injuries.

Brett McKay: Oh, so if these guys didn’t fight to the death, like that wasn’t the goal. How do they know when a battle was over? Like how long do these things last?

Alexander Mariotti: Same as MMA. You know, it’s interesting that we’ve worked out through how many games went on in an afternoon that your bouts were between three to five. You had rounds first of all because you had referees, you had one in the middle one in the side, the rudis and the secunda rudis. So exactly like today you had a guy in the middle of the fight, guy in the outskirts kind of giving you the opinion. They fought in rounds because again once this is the sort of interesting part of my work is when I was younger I spent a whole period, you know, I was an ex-athlete so I was very physical and I worked at the museum where we’ve rebuilt all the armor the weapons and we said, right how do these work and tried on the helmets. And I can tell you that when you’ve got one of these helmets on, and I played American football, it’s hard to have everything on. You know, you do short bursts because otherwise you’d be exhausted. So you got to take the helmet off.

So the gladiators would have been the same because your breathing is hugely restricted. Your vision is hugely restricted. They’re very uncomfortable helmets, even with padding, the weight of the armor bears down on you and you’re fighting in the Mediterranean heat. So they fought in rounds and they had points and the referee would of course then go ultimately to the crowd and say who won and people would give their opinion and then you would name the winner. So you know just the same way how does somebody win a boxing match or an MMA fight?

Brett McKay: Kind of give us an idea what the games are like. So if I were a citizen in Rome and I heard okay there’s games planned for this week, what would Rome be like? What would the Colosseum be like on that day of the games?

Alexander Mariotti:Well, I want everybody who’s listening to this to appreciate one thing. We live in a time where we can go to stadiums of 80,000 people. So we’re at a huge advantage that anyone has been throughout history to understand the gladiator games because we know what the sound of 80,000 people sounds like. We know when we go to the games that it’s an all day thing, just as it was in ancient times. And by the time you’re walking towards the arena, you can see it in your vision. You’ve got a whole bunch of very excited people. There’s that sort of energy in the air. You’re ready to go to some tailgating, some cooking and eating, which is what the Romans would have done. You’ve got your ticket in hand, which is called a tessera. It’s a coin. It has a number on it. So it doesn’t matter if you speak Latin or not. You can still today on the Coliseum, when you see the arches, it has numbers that correspond to tickets. So they had a gated ticketed system in 81 AD already. When you walk through the store, there’s a guy who checks your ticket, lets you through, you go up some stairs, and as you come out of the second set of stairs, you walk out onto the arena, onto the stands.

You find your seat, you get some food and drink, there’s somebody passing by that’s serving food, they’re serving wine. You’ve passed the souvenir stalls, you’ll probably go to that later depending how the game goes. You might have bought a flag for your team and you’re sitting there with your friends and all of a sudden the announcer starts playing music and announces the entry of the Emperor. So think how exciting you get to spend a whole day with the most powerful and important person in the world, the Emperor of Rome, there he is right there with you. And they tell you where the games are on. And as they tell you the reason for the games, the music begins and suddenly popping out of the ground are trees because underneath the sand of the arenas are 50 odd trap doors and lift and pulley systems. So they put trees on them so trees would be popping out of the sand and transforming the entire arena into a jungle. Because you are never going to visit the jungles of India, but you don’t need to because the Coliseum brings the empire to you.

Suddenly a beast hunter pops out of a trapdoor, lions pop out of another, and with an aerial view and music playing, a whole soundtrack, you’re going to watch a hunter hunt a lion. So the lion’s stalking him, you see it getting closer, the music builds and he turns around at the last minute, he starts stabbing the lion and the music builds, crescendos, he kills the lion, the games are over, the trees stop popping down the ground, sand, and it’s time for the halftime show. Acrobats, dancers, executions, and best of all, a raffle. You’ll get thrown to the stands, little wooden balls, open them up. If there’s a coin inside, there’ll be a number, keep a hold of it, and later they’ll call that number and you can win a horse, grain, even a villa. What a great guy the Emperor is. You start to see that democracy is overrated, you don’t get free stuff, But when you’ve got an emperor, you get free tickets, free food, free wine, free things. And the best part is yet to come. Because when 4 o’clock reaches and the weather gets a little bit more moderate, that’s when the gladiators start.

So music plays and out comes from the dugouts. You know, the lesser known guy build up the title fight. That’s why we’re here. This is the trilogy match between two gladiators. You know, one’s won one battle, one’s won another. This is the epic third that’s going to settle it. Who is the champion gladiator of the Coliseum? And as the music plays, a guy comes out, people cheer, music plays, another guy comes out, people cheer. And with music playing, you get to watch them fight. And then at the end, when your team wins and the crowd erupts, you get this feeling of euphoria, or you might be on the other side and get the feeling of absolute dejection. But then you leave, and for one entire day of your life, you aren’t an accountant, a lawyer, you were a champion gladiator, a beast hunter, you were somebody who got to spend time with the emperor, and then you go back to your normal life. And when we go to stadiums or we go to cinemas, we reenact all of that. That’s why we go to the cinemas to see gladiator, because we want to see these things, and we’re in a period where we can and we can experience them exactly as the Romans did.

Brett McKay: As you’re describing that, I was just thinking about the professional sports games I’ve been to. I mean, the big picture is the same thing, like the raffle, you know, if you’ve been to a sports game, you’ve done that. We don’t win villas. You might win some free Arby’s after the game.

Alexander Mariotti: You might get a t-shirt.

Brett McKay: You might get a t-shirt. Right. And then also the souvenirs. Like you always you got to pick up a souvenir. You can get a flag. Were there like souvenirs of like the specific gladiators? Could you buy like a mug with them?

Alexander Mariotti: Oh, yeah. Yeah. And there was also like retro ones, like vintage ones. So you’d go to the stalls and you’d be like, oh man, I remember this. My dad saw this one. This is a cool one. This is a collector’s piece. I’ll take this one. But you had statues and lamps and dolls of specific gladiators. You had commemorative bowls and so on of particular fights. So yeah, not, not any different, not any different at all. And of course you could buy food and people then the animals actually were butchered and then they were given to people and people, they did actually tailgate, they would cook their food while they were watching the games.

Brett McKay: That’s really interesting. All right. So the gladiatorial games, the gladiator games were huge. It was basically like NFL MMA for Roman and wrestling for the Roman Empire. Yeah.

Alexander Mariotti: Were put together. Like all our sports today have an element of it. Like I look at, you know, American football and it’s probably why I loved it so much and why I played it was because it kind of reminded me of being a gladiator. The helmets, the armor, the sort of clashing. But even MMA, of course, that’s ultimately the heart of what gladiatorial combat was, but wrestling’s like it because wrestling involves super humans. You look physically what the wrestlers look like. They’re not like us. I’m speaking for myself. There might be people who are 6’7″ out there and how many hundred pounds, but most of us aren’t. So, you know, when you were gladiator, you were the physical exception. You would have been six foot in a time when people were between 4’6″ to five foot, just as wrestlers today are six foot something and seven foot. You had music playing as you came out. There was an element of the fight, which wasn’t really real. You know, you weren’t aiming to kill each other. You were aiming to put on a show. I think that’s the sense of wrestling.

Brett McKay: Oh yeah. So when you say wrestling, you’re talking about like professional wrestling, like WWE or WWF wrestling.

Alexander Mariotti: WWE. That’s right. Yeah. I’m talking about The Rock. Like, and again, even the names, like the names of gladiators really mimic perfectly the names of wrestlers or wrestlers mimic the names of gladiators, you know, The Rock, The Undertaker. These are fantastic names because they evoke a feeling, an image, a persona and you had it with gladiators as well. You know, you just need to say Spartacus. Oh, wow. Okay. That’s a great name. Blade. We had one called Flamma, Fiamma, the Blaze. I mean, you can imagine a wrestler called Blaze and there was a gladiator called Blaze.

Brett McKay: That’s really cool. So why did they go away?

Alexander Mariotti: Well, they went away for the same, you know, the three things that changed the world, money, politics, and religion. So basically what happened was throughout the Roman Empire, because there was so many arenas, the priests of the Imperial cult, which is imagine it from an administrative point of view, you have people out in the provinces because the emperor doesn’t actually physically go there most of the time, who represent the emperor. And to show the locals that you are lucky to be in the Roman Empire, you get all the benefits, you know, like you do the sort of Starbucks of ancient times, you get civilization you get a Starbucks, a McDonald’s. Well in Roman times you get baths and you get a library you get a senate house and you get an amphitheater. And periodically the priest will put on games in honor of the Emperor. So the locals will be, you know, fantastic. I’ve got a local amphitheater and I’ve got people fighting for me because the Emperor is so kind. But the problem is that the people had to pay for them.

So Marcus Aurelius, to stop people ruining themselves financially to do this, puts a limit on how much money you can spend on a game, how much money the gladiators can earn. He basically puts gaps on them. And by the way, I feel that our modern sports are going to hit something very soon just like that. When you look at the astronomical quantities that players are paid, games cost to put on. You know, the Super Bowl, I was looking at the numbers, I mean, gosh, the amount of money that it takes to put on a Super Bowl is going to reach a level when the amount of money it costs is going to exceed the amount of money it makes. And then that’s when you’re going to have problems. That’s what happened with gladiatorial combat is that there were limits on how much people earned, how much the games could be, how much could be spent. So all of a sudden it wasn’t lucrative like it was. So the sort of heyday started to pass after 180 AD. It still goes on to 430 AD, but it doesn’t have the prestige it used to.

And I think a good example of this is baseball, where I don’t think baseball is quite as prestigious as it was, because the money’s kind of gone out of baseball. So, you know, if I’m an athlete, do I want to be a baseball player or do I want to be a basketball or an NFL player? Well, who makes the most money? Yeah, I think I’ll be an NFL player, thanks. And religion is ultimately, yeah, socially things change because Christianity came in, but again, the Christians were not so concerned with the well-being of the gladiators, the athletes, they couldn’t care less. They were more concerned that they wanted people to be less animalistic. And they felt that the games brought out the worst in people. So it just basically just faded away. And politics is because Rome was, of course, the capital of the empire. But the Emperor Constantine moved this to Turkey to Istanbul. And when Constantinople was founded, the public really had no power in Rome anymore. So the point of putting on the games is to win people over politically, to keep them happy, you know, distract them. But when they had no political sense anymore, political power, it made no sense. And they didn’t do it for them anymore. And of course, that’s where the Coliseum was. So it faded into history.

Brett McKay: So there’s been a lot of movies made about gladiators, and you’ve consulted on shows about gladiators. Do you have your like top three favorite gladiator movies?

Alexander Mariotti: My top movie, you know, I like, I love them all. I love them all because they all have aspects that I love. Obviously like Gladiator I was amazing because it brought the Coliseum to life. I don’t think anyone really had a sense of what the games were like visually until Gladiator came along. There’s this great shot where Maximus is fighting Tigris in the middle of the arena and it’s like a wide shot and you just see the whole arena and you realize people were just concentrated on two little figures in the middle. You know, I do love the series Spartacus because I think it gives you a real sense of what the gladiator was, his life was like, you know, the sort of sex, drugs and rock-a-roll of its time or sex, wine and I guess harp music, whatever the equivalent was in antiquity, probably opium, I suppose. But it really showed the sort of life of the gladiator inside the lotus. I thought that was great. And of course the sex involved because that was a huge draw.

You became a sex symbol, you know. Sex is a major drive for anybody and being a gladiator was a sure way to be just an object. And it’s amazing how many objects we find related to gladiators and sex from antiquity. So I like different shows for different aspects. And even Gladiator II. I have to say I really loved Gladiator II as well. I did some work on Gladiator II and I thought just the views of the Coliseum. Who’s ever seen a naval battle? We just got to sit and watch a naval battle in the Coliseum, brought to life with our technology. And how fascinating that to us it’s amazing. And then you think, imagine what it was like when you saw it in real life 2000 years ago. If it amazes us who have all sorts of spectacle to blow us away in technology, and yet we can still sit and see two ships in a Coliseum and go, wow, that’s cool. Imagine when you saw it in the amphitheater 2000 years ago.

Brett McKay: Last question, why do you think people continue to find gladiators so compelling, even in the 21st century?

Alexander Mariotti: I think it’s an easy one. I think there’s a variety of reasons. The first is because we still admire virtus, because we still admire strength and courage and resilience. Just like the Romans did. You see it in our superstars and our sports stars, our superheroes. The gladiators were the first version. I think second reads because we see ourselves more as the gladiators. They’re the most relatable of all the characters of antiquity because we don’t see ourselves in emperors or nobles. Very few of us do. We don’t live that life. But the gladiator is the commoner. It’s the guy who comes from nothing and makes his way up the ranks and makes fortune and fame and success. I’m still talking about them. But I also think that especially personally, and I think most people can sort of associate with it, is that there’s a great level of psychology. The arena was a representation of life. So when you saw animals fighting people, that was the savagery of wild and how man can confront even a lion.

It’s terrifying, but you can do it. You know, you have to be brave, you have to be full of virtus. When you saw criminals getting executed, you saw this chaos, but there’s order and bring order. And when you saw the gladiator, you saw a representation of how we live. We all find ourselves in a fight at some point in our lives. Not a physical fight. It can be an emotional or a mental struggle. It’s still battle. Life is war. It’s a fight. And somebody ultimately holds our fate in their hands. So really, if you look at it, you know, it’s a sort of metaphor there. The gladiator is us, the arena is life, and the emperor is whatever we’re fighting, whether it’s health or bad luck, who’s going to hold sway of our lives. And they inspire us to fight and to succeed, to face death and overwhelming odds of courage. And who cannot be inspired by that?

Brett McKay: Well, Alexander, this has been a fascinating conversation. Where can people go to learn more about your work?

Alexander Mariotti: Oh, that’s very kind of you, Brett. Thank you. You can find me on my website, alexandermariotti.com, or follow me on Instagram as thegladiatorhistorian. I usually put out all sort of my talks or appearances, or come visit me in Rome. I’m in Rome. I do some work over there. So whether Rome and London, you can come and find me at the British Museum or usually around the Coliseum somewhere.

Brett McKay: Well, Alexander Mariotti, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Alexander Mariotti: Brett, as they say, strength and honor. And thank you so much.

Brett McKay: My guest today is Alexander Mariotti. He’s a gladiator historian. You can find more information about his work at his website, alexandomariotti.com. Also check out our show notes at aom.is/gladiators. Where you can find links to our resources we delve deeper into this topic. Well that wraps up another edition of the AOM Podcast. Make sure to check out our website at artofmanliness.com, where you find our podcast archives, and check out our new newsletter. It’s called Dying Breed. You can sign up at dyingbreed.net. It’s a great way to support the show directly. As always, thank you for the continuous support, until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding you to not listen to the AOM podcast, but put what you have heard into action.