A lot of self-improvement advice and content feels empty. And there’s a reason for that. It often offers routines and habits to practice, but doesn’t offer a strong, overarching reason to practice them.

That’s why the self-improvement advice of the Founding Fathers is particularly compelling. Though they were imperfect men, they had a clear why for trying to become better than they were. For the Founders, life was about the pursuit of happiness, and they equated happiness with excellence and virtue — a state that wasn’t about feeling good, but being good. The Founders pursued happiness not only for the personal benefit in satisfaction and tranquility it conferred, but for the way the attainment of virtue would benefit society as a whole; they believed that political self-government required personal self-government.

Today on the show, Jeffrey Rosen, a professor of law, the president of the National Constitution Center, and the author of The Pursuit of Happiness, shares the book the Founders read that particularly influenced their idea of happiness as virtue and self-mastery. We talk about the schedules and routines the Founders kept, the self-examination practices they did to improve their character, and how they worked on their flaws, believing that, while moral perfection was ultimately an impossible goal to obtain, it was still something worth striving for.

Resources Related to the Podcast

- AoM’s series on Benjamin Franklin’s 13 Virtues

- Ben Franklin Virtues Journal available in the AoM Store

- AoM Article: Young Benjamin Franklin’s Plan of Conduct

- AoM Article: Thomas Jefferson’s 10 Rules for Life

- AoM Article: The Libraries of Famous Men — Thomas Jefferson’s Recommended Reading

- AoM Article: The Best John Adams Quotes

- AoM Article: George Washington’s Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation

- AoM Podcast #366: Teach Yourself Like George Washington

- AoM Article: The Spiritual Disciplines — Study and Self-Examination

- Tusculan Disputations by Marcus Tullius Cicero

- The Golden Verses of Pythagoras

Connect With Jeffrey Rosen

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. A lot of self-improvement advice and content feels empty, and there’s a reason for that. It often offers routines and habits to practice, but doesn’t offer a strong, overarching reason to practice them. That’s why the self-improvement advice of the Founding Fathers is particularly compelling. Though they were imperfect men, they had a clear why for trying to become better than they were. For the Founders, life was about the pursuit of happiness, and they equated happiness with excellence and virtue. A state that wasn’t about feeling good, but being good.

The founders pursued happiness not only for the personal benefit and satisfaction and tranquility it conferred, but for the way the attainment of virtue would benefit society as a whole. They believed that political self-government required personal self-government. Today on the show, Jeffrey Rosen, professor of law, president of the National Constitution Center, and the author of The Pursuit of Happiness, shares the book the founders read that particularly influenced their idea of happiness, of virtue, and self-mastery. We talk about the schedules and routines the founders kept, the self-examination practices they did to improve their character, and how they worked on their flaws. Believing that, while moral perfection is ultimately an impossible goal to obtain, was still something worth striving for. After the show is over, check out our show notes at aom.is/pursuitofhappiness.

All right, Jeffrey Rosen, welcome to the show.

Jeffrey Rosen: Great to be here.

Brett McKay: So you got a new book out called The Pursuit of Happiness, How Classical Writers on Virtue Inspired the Lives of the Founders and Defined America. And this is a really fantastic book. I really loved reading it. It was great getting into the minds of the founding fathers. And what you do is you take readers on a journey through the books that the founding fathers read that shaped their thinking as they were trying to figure out what is this new government gonna be in the United States. And specifically, you wanted to figure out what Thomas Jefferson meant by the pursuit of happiness in the Declaration of Independence. What led you to take this exploration?

Jeffrey Rosen: It was a series of synchronicities during COVID that led to this project. First, I was rereading Ben Franklin’s attempt to achieve moral perfection in his 20s. He made a list of 13 virtues that he tried to live up to and practice every day. Classical virtues, industry, temperance, prudence. He saves the ones he finds hardest for last, which is humility, and puts X marks next to the virtues where he fell short. He tried it for a while. He found it was depressing ’cause there were so many X marks, but he was a better person for having tried. I noticed during COVID that he chose as his motto, a book by Cicero that I’d never heard of called The Tusculan Disputations. And he said, without virtue, happiness cannot be. A few weeks later, I was at the Boar’s Head Inn in Charlottesville, Virginia, which is on the UVA campus. And on the wall, I noticed this list of 12 virtues that Thomas Jefferson had made for his daughters.

They looked a lot like Franklin’s silence, resolution, industry, and so forth. Jefferson leaves off one that’s on Franklin’s list, which is chastity. But Jefferson chooses as his motto also this Cicero book, The Tusculan Disputations. So basically during COVID, I thought I’ve got to read Cicero ’cause it’s so important to Hamilton, or rather to Franklin and to Jefferson, but what else to read? And then I found this amazing reading list that Jefferson would send to anyone who asked him when he was old how to be educated. And it’s very comprehensive. It has literature and political philosophy and science and history and a very rigorous schedule about when you read which books at what time.

It’s kind of 12 hours of reading starting before sunrise and going until evening. But what caught my eye was the section called moral philosophy or natural religion or ethics. And there was Cicero, The Tusculan Disputations, along with Marcus Aurelius and Seneca and Epictetus, other stoic and classical philosophers, as well as Enlightenment philosophers like Francis Hutcheson, and Bolingbroke, and David Hume. So basically, I thought, I’ve got to read these books. I’ve had this wonderful liberal arts education. I’ve studied history, and politics, and English literature, and American literature, and law with great teachers in wonderful universities.

I missed these books ’cause they’d just fallen out of the curriculum by the time I was in college. During COVID, I resolved to read the books. I followed Jefferson’s schedule, got up before sunrise, read for an hour or two, watched the sunrise. And what I learned transformed my understanding of the pursuit of happiness, how to be a good person and how to be a good citizen. And all of these books confirmed what Cicero said that for the classical philosophers, happiness meant not feeling good, but being good, not the pursuit of immediate pleasure, but the pursuit of long-term virtue. And they defined virtue as self-mastery, self-improvement, character improvement, being your best self, and mastering your unreasonable passions or emotions so you could achieve the calm tranquility that for them defined happiness. So that was a wonderful experience in rediscovering Jefferson’s understanding of the pursuit of happiness.

Brett McKay: Okay. So, I hope we can dig into some of these books and their schedules. It was really fascinating to get a peek at how these guys thought about self-improvement, how they scheduled their days in order to fulfill those goals. But let’s talk about the intellectual environment these guys were growing up in that caused them to turn to classical writers in order to figure out what it means to live a good life. So they were products of the Enlightenment. How did the Enlightenment shape the founders’ reading habits?

Jeffrey Rosen: It shaped it completely. All of their reading habits, their whole worldview, their political and their moral philosophy is based in this shining faith in the power of reason and the ability of individuals thinking for themselves to discover the truth and align their lives with divine reason, which they thought was a synonym for the divine. And there’s just such a inspiring faith in the power of reason, the ability of reason to be reconciled with faith, and the ability of reason to achieve self-mastery. This antithesis that you find constantly in the Enlightenment literature between reason and passion comes from Pythagoras, of all people, in addition to reading the triangle and inventing the harmonic system of triads and fifths.

It was Pythagoras who drew this antithesis between reason in the head and passion in the heart and desire in the stomach. And he said the goal of life is to use our powers of reason to moderate or temper our unreasonable passions and desires so that we can achieve calm tranquility, self-mastery, and live according to reason, which is not only a right but a divine duty. And the Enlightenment philosophers like Locke and Hutcheson and The Whig critics of the English tyranny all pick up this antithesis between reason and passion. Sometimes they disagree about whether or not reason is strong enough to overcome passion in particular circumstances. But it’s all in the service of moderation, the Aristotelian mean. They’re not saying that we should avoid passion or emotion, but just that we should moderate our unproductive passions or emotions, in particular, anger and jealousy and fear, so that we can achieve productive emotions like tranquility, prudence, justice, and fortitude.

Those are the classical virtues that were so important to all the founders. So just this wonderful consonance between the classical and the Enlightenment faith in reason, and a tremendous belief that the individual applying his or her powers of reason is able to achieve calm self-mastery.

Brett McKay: And another theme you see in the Enlightenment, they pick this up from the ancient writers from Rome and ancient Greece, was that you had to… I don’t wanna say, maybe, yeah, you had a duty to improve yourself because you wanted to live a flourishing life yourself. But the idea is that as individuals pursued this idea of excellence or Arete, eudaimonia, of flourishing, that will allow for a flourishing society.

Jeffrey Rosen: Exactly. You’re so right to phrase it as a duty to improve yourself. And arete, as you say, is the core of Aristotle’s famous definition of happiness. In the Nicomachean Ethics, he defines happiness as an activity of the soul in conformity with excellence or virtue. And because the phrase excellence arete is not self-defining and nor is virtue, it can be confusing to us. But it really means an excellence of the soul, a moderation of the soul, a self-control, so that, as you say, we can achieve our potential. And we have not only a right to achieve our potential, but a duty to use our gifts and talents as best we can so that we can be our best selves to use the modern formulation of it, and to serve others. And in so doing, we’re living a life according to reason, aligning ourselves with the divine harmonies of the universe and fulfilling our highest purpose.

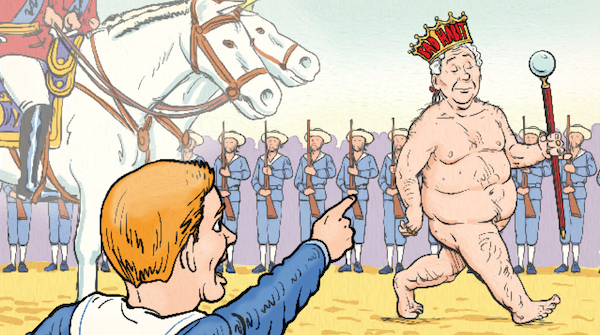

Brett McKay: And going back to the social element of this, I think the founders were thinking, we’re gonna try this Republican form of government where there’s more direct participation by individuals in their government. In order for that to work, we need everyone to be like, I think Jefferson called this, like you had to be kind of an aristocrat of virtue and an aristocracy of virtue and talent. You couldn’t just be this sort of dolt who just like passively lived life. If you’re going to participate in government, you yourself had to have sort of this aristocracy of the soul.

Jeffrey Rosen: Absolutely. Very well put. And it’s this deep connection between personal self-government and political self-government. I really hadn’t understood this before reading the moral philosophy. But the founders think that unless we can achieve a harmony of soul in the constitution of our own minds, we won’t be able to achieve similar harmony in the constitution of the state. And more specifically, unless we can restrain ourselves from being our angriest selves and tweeting and attacking and retreating into our tribal factions, we won’t be able to deliberate in common and pursue the common good. The founders are not at all sure that the experiment will work. Never before in human history have, as a nation, tried to test the experiment of whether we can be governed by reason and conviction, not force or violence, as Hamilton says. But that’s the whole purpose of the experiment. And it’s all based on Republican virtue.

Brett McKay: Okay. So the founders believed this idea that you could develop yourself, you can improve yourself through reason, and they called it faculty psychology, where you try to use reason to temper your passions. You don’t kill your passions. You use reason to direct your passions to the good. Let’s talk about some of these books that influenced their thinking. Let’s talk about that first one you mentioned, Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations. All the founders read this book. A lot of them quoted from it in their commonplace books or in letters. Tell us about this book. Who was Cicero and why did he write Tusculan Disputations?

Jeffrey Rosen: Cicero, the great orator and political philosopher and moral philosopher of the Roman era, writes the Tusculan Disputations to console himself after the death of his daughter, Tullia. He’s also out of political favor and he retreats to his villa in Tusculan and sets out to write a manual. Amazingly, it’s on grief and on the management of grief. And it’s really striking that the central source for the founder’s understanding of The Pursuit of Happiness was a book about grief management. And it is divided into chapters about how to focus on controlling the only thing we can control, which is our own thoughts and emotions and not the activities or fate that befalls others.

This is the famous Stoic dichotomy of control. And Cicero is applying it to try to console himself after the death of his daughter. In its most rigorous form, the Stoic advice about death was even grief over the loss of a loved one is not reasonable because if you look at things reasonably, you want to accept whatever is as it ought to be and be grateful for the happy times you had with your daughter and recognize that things cannot be in any other way. This is unrealistic for most people. Abigail Adams thought that the Stoic advice of completely overcoming grief was too rigorous. But Jefferson finds it very consoling when his dad dies. And he’s about 14 years old, and his beloved father, Peter Jefferson, has just died. And Jefferson copies out in his commonplace book passages from Cicero to console himself. And it’s just remarkable to watch his mind work as he copies out these passages, including the famous passage about how happiness is virtue, which is tranquility of soul, which is an old man in his 70s. He would send out to young kids who wrote to him asking about the secret of happiness.

Brett McKay: How did you think this book influenced Thomas Jefferson when he was developing the declaration of independence?

Jeffrey Rosen: Well, when Jefferson was developing the Declaration, he said he wasn’t doing anything original, but was just channeling the philosophy of the American mind by distilling ideas that were commonplace from public writers such as, and he cited in particular, Cicero, Aristotle, John Locke, and Algernon Sidney. What I did is set out to read all the sources that Jefferson relied on by looking first with the moral philosophy on his reading list and doing word searches for the pursuit of happiness. And what just really was striking is that almost all of those sources, the Stoic and the Enlightenment sources, actually contained the phrase, the pursuit of happiness. And defined it as virtue rather than pleasure-seeking.

And then I set out to read the other documents that Jefferson had in front of him when he wrote the Declaration that talked about happiness, including George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights and James Wilson’s Reflections on the Extent of Legislative Authority in Britain. And they also contain the phrase pursuing happiness or pursuit of happiness and defined it in this sense of virtuous self-mastery. So what’s so striking is Cicero is just one example, and really the most frequently-cited example, ’cause so many of the Enlightenment sources themselves cite Cicero. But one example of overwhelming consensus about the understanding of happiness as virtue, shared by the classical sources, the Christian Enlightenment sources, Whig revolutionary sources, and civic Republican sources, and Blackstone, the legal commentator. In other words, this is everywhere. It’s completely a ubiquitous, universally-shared understanding of happiness, but Jefferson roots it in Cicero.

Brett McKay: Okay, so Cicero had a very stoic idea of virtue. And I think it’s interesting that he used in these other classical philosophers as well as Enlightenment philosophers and later Thomas Jefferson, they said the pursuit. It wasn’t achieving happiness. It’s the pursuit. There’s a virtue in just trying to be virtuous. And if you think of virtue or having a flourishing life as a practice instead of an acquisition, that’s what we’re going for.

Jeffrey Rosen: Exactly. And Cicero himself says that the goal, the quest is in the pursuit, not in the obtaining. ‘Cause by definition, perfect virtue is unattainable. Jesus enjoins us to attempt to be perfect, but only Jesus can be perfect. Or Socrates, or Pythagoras, a handful of sages throughout history can approach perfection. But for ordinary humans, it’s just the quest. And every day you’re gonna fall short and fail, but you can attempt to be more perfect as Franklin so memorably said when he imagined life like a series of printer’s errors that he hoped could be corrected in a future edition by the author. It’s a very humane, but also demanding philosophy. We have a duty, as you said, to try to become more perfect, not only every day, but every hour of the day to try to use your talents, your time to stay focused, live in the present so you can achieve your potential all the time, recognizing that we’re gonna fall short and that the quest itself is the pursuit of happiness.

Brett McKay: So one of the things that most of the founding fathers did in this pursuit of happiness, in this pursuit of using reason to temper their passions, is they did self-examinations, daily self-examinations. You mentioned Ben Franklin’s, we can get into this a little bit more, but the guy that inspired these daily self-examinations was Pythagoras. Tell us about the Pythagorean self-examination and what the founding fathers took from that.

Jeffrey Rosen: Pythagoras is so inspiring. And I hope listeners will check out his 76 golden verses, ’cause they were really well-read in the founding era. They’re really accessible and just good practical advice about how you can try to be more perfect. And the core of the Pythagoras system is daily self-examination. Every night before bed, Pythagoras says, make a list of how well you’ve done and how well you’ve fallen short of trying to achieve the virtues of temperance, prudence, courage, and justice, and try to do better the next time. Pythagoras I thought of him as the triangle guy, but he lives on the Isle of Croton as a guru, as a divine figure.

He’s surrounded by disciples who emulate his rigorous asceticism in drink and eating. He’s a very committed vegetarian, as Ovid describes in his great account of Pythagoras in the Metamorphosis. He has this weird exception for beans. You’re not allowed to touch beans, and his disciples rather die than touch beans, which he thinks resemble fetuses and have the spirit of life in them. But it’s all about trying to achieve perfection as a human being. Pythagoras tells his disciples to first be good and then live like gods. And the way that you live like gods is by reverencing yourself. That’s Pythagoras’s motto. And you do that through extraordinary mindfulness and self-discipline and moderation. And that was his contribution and his central distinction between reason and passion, as I said, ends up being the core of classical moral philosophy.

Brett McKay: We’re going to take a quick break for a word from our sponsors.

And now back to the show.

Well, tell us about some of the founding fathers, Pythagorean self-examinations they did. So Ben Franklin famously had his 13 virtues and even developed this chart to track how he was doing. We did a whole series. When I first started AOM back in 2008, we did a whole series about Ben Franklin’s 13 virtues. I even made a Ben Franklin’s virtue journal that people could buy. But tell us more about this for those who aren’t familiar.

Jeffrey Rosen: That’s so great that you did that. I first encountered the virtues a few years ago in the Hebrew version. It turns out there was a Hasidic rabbi in 1808 who really admired Franklin and translated the virtues into Hebrew and offered them up for Jewish Seekers of Character Improvement, or Mussar, which is the Hebrew word. And a local rabbi in Washington, DC recommended it to a friend and I, and we tried it for a bit making a list every night of how we’ve fallen short with the various virtues of temperance and prudence and so forth. Like Franklin, we found it really depressing ’cause you’re always losing your temper and falling short every day. But it was helpful in creating mindfulness about how to live.

And Franklin got it not only from Pythagoras, but also from John Locke, whose book on education recommends a kind of self-examination and virtue. This led Franklin to form his famous club or junto to join of men who were devoted to self-improvement in the hope of creating a united party of virtue of fellow self-improvement seekers around the world. And the basis of it is they’re kind of support groups. You’re supposed to do it with friends and look closely at yourself and share what you find with others and try together to engage in self-improvement. Franklin, although he gave up the Virtues Project in his 20s ’cause he found it so rigorous, never abandoned his hope of writing a book called The Art of Virtue. And to the end of his days, he hoped that he would bring all of his wisdom into one place. He never quite did, but the Virtues Project is the most enduring legacy that he could give us ’cause it tells us in a practical way how to practice the art of virtue.

Brett McKay: Yeah. So he had these 13 virtues that he focused on and he developed a chart for himself where he would put a black dot if he didn’t live up to that virtue. And the idea was to have the chart as blank as possible. The more dots on it, the more bespeckled his character was. And so, yeah, the 13 virtues, for those who aren’t familiar, we had temperance, silence, order, resolution, frugality, industry, sincerity, justice, moderation, cleanliness, tranquility, chastity. Then he added humility at the end. And as you said, Thomas Jefferson had a similar set of virtues he tried to live in his own life. And the other thing that Franklin did in addition to developing this virtue chart and kind of being very rational about his moral development, he had a schedule that he set for himself and as part of his daily examination in the morning, he would ask himself, what good shall I do this day? And then at the end of the day, he would ask the question to himself, what good have I done today? And he was just, he’s trying to do that Pythagorean thing. It’s like, how have I gotten better throughout this day? And again, Thomas Jefferson did a similar thing as well.

Jeffrey Rosen: So true. And it’s all about the schedule. That’s the most striking practical takeaway from the way all of these founders lived. They were very mindful of time and would make lists of their schedule and would stick to the schedule. They develop habits starting in youth about waking up early. Franklin famously, early to bed, early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise. He kind of condenses that from a more lugubrious version in an English virtue source. And Jefferson’s reading list has a really demanding schedule associated with it. And all of the founders keep up this mindful schedule of rigorous reading and writing until the end of their days. And there’s something so moving about seeing Jefferson and Adams as old men still getting up early, doing their reading, trading ideas about the latest books that they’ve read, keeping up their correspondence. They fell short on so many levels in the pursuit of virtue as we all did. But the one virtue that many of them practiced until the end was industry just ’cause they developed the habits ever since they were kids.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I found that the most inspiring thing from this book is how these guys really believe they can improve themselves and they set their time, their schedule to make that happen. A lot of times we have these sort of vague ideas like, oh, I wanna become better. And it doesn’t go anywhere ’cause we don’t make it concrete. All these guys set a very strict schedule for themselves. Yeah, Ben Franklin, he had a schedule. He was up at 5:00. He says, rise, wash, and address powerful goodness. Contrive business and take the resolution of the day. That’s when he asked himself, what good shall I do this day? That was from 5:00 until 7:00. 8:00 till 11:00, he worked. From 12:00 to 1:00, he read and overlooked his accounts, did some lunch, had a working lunch. 2:00 to 5:00, did some more work. And then 6:00 to 9:00, he was kind of putting things in their place, supper, music or diversion or conversation, and then do his examination of the day. And then from 10:00 to 5:00, he slept. And then Thomas Jefferson, like you said, he had this schedule that he started when he was a kid. He was up early. And not only was he doing the reading that he set for himself, he also scheduled physical exercise.

Jeffrey Rosen: Absolutely. That’s the most inspiring thing for me too. It’s so remarkable to see how much these guys accomplished by mindfulness about time and keeping up their youthful schedules. And it changed my life. I followed the Jefferson schedule, got up, did my reading, watched the sunrise. I found myself writing these weird sonnets to kind of sum up the wisdom that I’d learned just ’cause I wanted to kind of encapsulate it in some form and found that lots of people in the founding era wrote sonnets or poems about this literature. And since finishing the book, I’ve tried to keep up a version of the Jefferson schedule.

And the simple rule that I’m carrying forward is I’m not allowed to browse in the morning until I’ve done reading or some other creative work. And there’s a difference between reading books and browsing blogs and just being not allowed to check email or do anything else until I’ve read a real book. It’s changed my life ’cause I’ve gotten out of the habit of reading for stuff that was outside of my immediate deadlines. And now reading books just to learn is transformative. And this is what so inspired me about the founders. I mean, just Adams and Jefferson, just think of it in their 70s and 80s, still excitedly learning about Pythagorean moral philosophy and Adams exploring the connections between Pythagoras and the Hindu Vedas. And they never stopped learning and growing. And that for them was the definition of the pursuit of happiness, being lifelong learners.

And if they could find time with all the depredations of 18th century living and the freezing cold and the disease and just the sheer difficulty of life and the difficulty of having access to books, which they just had to yearn for to get imported, and then I contrast that with the fact that I was able to write this whole book sitting on my couch because all the books in the world are free and online. And all I need is the self-discipline to actually read them and to swipe left to the Kindle and not right to the blog or to email. So it’s very inspiring. The founder’s schedules in their own lifetime inspired others. And I’m so grateful to have encountered their mindfulness about time.

Brett McKay: So yeah, I think the big takeaway from the founders that I got is like, yeah, if you have a goal of self-improvement, you got to put it on the calendar. If it’s not on the calendar, it’s not gonna happen. What I thought was interesting too, and you do this in the book, is you focus on a founder in each chapter. And it seems like each founder had their own personal issues that they were trying to sort out and master with their reading. Let’s talk about John Adams. What was John Adams’ biggest flaw that he worked on during his entire life? And then we’ll talk about how his reading helped him conquer that or master it.

Jeffrey Rosen: His biggest flaw was vanity. Anyone who’s a fan of the old musical 1776 remembers, I’m obnoxious and disliked, that cannot be denied. And he’s constantly ridiculed for his self-importance. He wants the president to be called his elective majesty and people mocked Adams as his rotundity. And he’s losing his temper all the time and storming that he’s not getting enough credit for the revolution. He says Adams was the actual author of the Declaration of Independence. He speaks of himself in the third person. And it’s not fair that Jefferson and the Grand Franklin are getting all the credit. And his wife Abigail recognizes this as his flaw. When they’re courting, they decide to make a list of each other’s faults, which is a dangerous dating strategy, but they, in the Pythagorean spirit, do that.

And the flaws that Abigail notes for John are that people think that he’s intellectually intimidating and haughty ’cause he’s so brilliant. You know, she puts it in a generous way. And then he counters, well, your flaws are you’re not practicing the piano or reading enough and you’re pigeon-toed. And she says, “Well, a gentleman shouldn’t comment on a lady’s posture.” But Adams recognizes his own vanity and self-importance and is constantly trying to subjugate it ever since he was a student, a young student in college and copying passage from the classics into his diary.

And the most endearing thing about Adams is that he wears his heart on his sleeve and he, in the end, does conquer this ruling passion of vanity. He has terrible blowouts with two close friends, Mercy Otis Warren, the anti-federalist, and Jefferson, who he fights with in the famous election of 1800. But the most significant thing is that he reconciles with both of them. And after falling out over politics, he gets back together with Mercy Otis Warren and certifies to her poetical genius in writing the plays that sparked the revolution. And with Jefferson, it’s just incredibly moving that he’s able to set aside all the partisanship that divided them in that election and to have this spectacular correspondence as old men where they confess, Jefferson says, “I love you.” It’s really very striking and beautiful. So that’s Adams. And he is quite relatable, to use our phrase, in both his struggles with his own vanity and ultimately his success in overcoming it.

Brett McKay: In his diary he talks about this. He says, “Vanity, I am sensible is my cardinal sin and cardinal folly.” And then he says this, “Oh that I could conquer my natural pride and self-conceit acquire that meekness and humility which are the sure marks and characters of a great and generous soul and subdue every unworthy passion.” Yeah, he was very self-aware and I think that’s the big key with all the founding fathers, they were self-aware of their flaws. They might not have been successful all the time in conquering them, but they kept working at it. And I wanna talk more about Abigail Adams ’cause I thought it was really interesting. Their marriage is… We have all their letters so we could see their correspondences. And a lot of the times they were talking about moral philosophy and how we can become better people so that we can form this new country that we’re trying to do here. The takeaway I got from there is the importance of another person in your own personal development. You can’t do it on your own. You can’t do it in a vacuum.

Jeffrey Rosen: That’s a great way to put it. Yeah, it’s so moving to see John and Abigail engaged in this mutual quest for self-improvement. They have a romantic partnership and intellectual partnership and a joint commitment to self-improvement. And Abigail gets it from the same classical moral philosophy and the same Enlightenment novels and poems that John does. And she’s not allowed to go to Harvard the way the guys are but she educates herself by reading books of the classics recommended by John and by his friend, Richard Cratch. And she takes from her reading of Alexander Pope and Lawrence Sterne, one of her favorite novelists and others, the central importance of using your powers of reason to subjugate your passions. And she’s always exhorting John and their son, John Quincy, and their other kids to be perfect. And I thought that having a Jewish mom was tough. Having a Puritan mom was even tougher for John Quincy Adams ’cause she’s constantly telling him, “Subjugate your passions.” She loves to quote the proverb, “He who’s slow to anger is greater than he who’s conquered a village,” and endlessly telling her kids, her husband and herself to be better all the while rooted in this great moral philosophy.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Abigail and John’s marriage is very inspiring and again that idea of bringing in another person into your personal development, you see that with Ben Franklin, you mentioned he started the the Junto or the Junto. It’s like a mutual self-improvement club where everyone got together and they shared, here’s what I’m working on, how can I get better? So I think we’re coming up with a great formula here for like the founder’s guide to self-improvement. One, read great books. Two, practice daily self-examinations. And then three, make sure you have another person. You’re doing this with other people ’cause you can’t do it on your own.

Jeffrey Rosen: Exactly, that’s just it, and read every day and read deeply and rediscover the radically-empowering practice of deep reading.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about George Washington so we think of George Washington, we see pictures of them or statues and he’s very regal, stoic-looking, unflappable but this guy, he’s a redhead.

Jeffrey Rosen: Sure.

Brett McKay: We see him in his white wig but he was a redhead. He had a fire, he was passionate. Tell us about how the classics helped Washington get a handle on his temper.

Jeffrey Rosen: Washington loves Seneca, whose essay on time is so inspiring. Time is a gift repaid by industry by squandering it. What fools these mortals be, says Seneca in the famous phrase quoted by Shakespeare. And Washington is obsessed with time. He’s got clocks everywhere at Mount Vernon. He keeps up a rigorous daily schedule, always eating and exercising and doing his work at the same times and he struggles ever since he was a kid to control his temper. He’s got a very critical mother, and Ron Chernow, his great biographer, thinks it may have been Washington’s effort to control himself in the face of his mother’s nagging that led to his devotion to self-mastery.

He’s observed to lose his temper in public on very few occasions. It’s so notable ’cause it’s so rare, both on the battlefield and in the White House or in the presidency and his power comes from his self-mastery, and the moments when he’s viewed as greatest are these moments where he’s mastering himself. At Newburgh, when the soldiers are rebelling, he exhorts them to achieve patience in not mutinying, but waiting for Congress to make them whole and give them their back pay. And he mounts the temple of virtue and makes an appeal for self-mastery and the soldiers weep because they’ve never seen him confess weakness before as he does when putting on his reading glasses. And really, it’s just the force of Washington’s towering character that makes him the greatest American of his age by all accounts. He presides over the Constitutional Convention. He doesn’t say much. He practices silence and self-control, but it’s the self-mastered presence of his towering authority that allows the whole convention to create a strong presidency ’cause they know he’s gonna be the president, and they trust him and they revere him. So Washington really appears almost greater, the closer you look at him, and his greatness comes from his self-mastery.

Brett McKay: So one character that I found incredibly relatable was John Quincy Adams. This is John Adam’s son. Tell us about John Quincy’s personality and disposition.

Jeffrey Rosen: I think he’s my favorite of the bunch because he’s both so relatable and so transparent about his own struggles to master his passions and to achieve his potential. As we said, he’s got his mom just on his case from the very beginning, telling him to master his passions. And this creates this lifelong sense that he’s not doing enough. There’s that amazing moment when he’s in his early 30s. He’s just turned down a Supreme Court appointment. He’s ministered to St. Petersburg and he writes in his diary, “I’m 30 something years old. I haven’t achieved anything. I’m not working hard enough, I’m spending too much time at the theater and I’m drinking too much. If only I could have more self-discipline, I might have ended war and slavery.” He puts a very high bar for himself.

But then he has this incredible challenge as these knights of the soul. He’s in the White House, and his oldest son, George Washington Adams, commits suicide. The boy can’t take the pressure of the name George Washington Adams and also being Adams’s oldest son. And he descends into alcoholism and jumps off a steamship. And Adams is crushed by the extraordinary sorrow of this loss. And he doesn’t know if he can continue. What does he do? He spends a year re-reading Cicero in the original, in particular, his favorite book, The Tusculan Disputations. He writes sonnets in the morning based on his reading. And he emerges from this after losing the presidency and determines to reinvent himself as the greatest abolitionist of his age. And he denounces slavery on the floor of Congress. He introduces a constitutional amendment to end slavery. And he dies on the floor of Congress after voting against the Mexican War, he collapses of a stroke. And while he’s on a couch, his last words, which he murmurs are, “I am composed.” And he gets this from Cicero, from the Tusculan Disputations, that the perfectly composed man is he who’s achieved the tranquility of soul that defines virtue and happiness. It’s this incredibly mindful, brave. And virtuous life and death, all within the framework of classical moral philosophy.

Brett McKay: I think John Quincy, he probably had depression. He seemed like he was a depressive. He was focused on the negative a lot. You can see that in his diary entries. He did a lot of rumination. He’s like, “Oh, I’m a total screw-up. I wasn’t a Supreme Court justice. What’s going on?” And I think that’s relatable. That’s another thing about John Quincy is he used his diary or his journal as another tool in his self-improvement. All the other founders did this as well. They used their diary as almost like a therapist. They used their writing as a way to use reason to temper their passions.

Jeffrey Rosen: Completely. I completely agree about how relatable he is. And it’s perhaps the greatest diary of any American president ’cause it’s so candid and so transparent. And so he’s really hard on himself, but he is always trying to do better. He did struggle with depression. And as you said, he does use the diary as an antidote to it. And he also uses Cicero as an antidote to depression ’cause the whole point of the philosophy, of course, is to view things realistically, to focus on controlling your own thoughts and emotions, which is all that you can control. He’s the Boylston professor of rhetoric at Harvard and gives lectures on how to control the passions to be an effective advocate as well as to be a happy person.

He uses those lectures and those tips in arguing the great Supreme Court Amistad case, freeing the Amistad captives, which folks may remember from a recent movie. And he hadn’t been a abolitionist before his reflection, but he becomes convinced that slavery violates the Declaration of Independence and the Bible. And he reads the Bible very closely and chooses a passage where Jesus promises liberty to all the captives and says that that’s a prophecy of the end of slavery.

There’s also this amazing speech that Adams gave on the Jubilee of the Constitution in 1839 about the urgent importance of studying the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution to save the Republic. And he says, he quotes the book of Deuteronomy and says, “Take these principles of the Declaration and the Constitution and put them as frontlets between your eyes, whisper them to your children before you sleep and while you wake and make them the very keystone of the arc of your salvation.” It’s done with such messianic fervor. And he really believes that these principles are key to ending slavery and preserving the republic…

Brett McKay: Okay. So, the founders we’ve talked about, it’s all about developing your own personal virtue. But the idea is that as individuals pursue this idea of excellence or flourishing, that will allow for a flourishing society. So like we said, take away, read great books, never stop reading, reread them, set a schedule for yourself for your own virtue development, have friends who can help you in that process. And I think from John Quincy, we can learn keep a diary, use your diary as a way to work through this stuff. I wanna go back. I just saw, I just came across this. You mentioned that Jefferson had this list of books that he would recommend over and over again. And here they are. We’ll put a link to this in the show notes as well. But you have a selected list here. There’s 10 books.

You have Locke’s Conduct of the Understanding in the Search of Truth, Xenophon’s Memoirs of Socrates. Epictetus, a Stoic philosopher. Marcus Aurelius, another Stoic philosopher. Seneca, another Stoic philosopher. Cicero’s Offices, another Stoic. Cicero’s Tusculan Questions or Disputations. Number eight, Lord Bolingbroke. I like that name. Bolingbroke’s Philosophical Works. Hume’s Essays and Lord Kames’s Natural Religion. Those are those 10 books those who wanna check that out. Well, Jeffrey, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book and your work?

Jeffrey Rosen: Constitutioncenter.org. It’s the most amazing platform that the National Constitution Center offers. The core of it is an interactive constitution that’s now gotten 70 million hits since we launched in 2015 and is among the most Googled constitutions in the world. You can click on any clause of the constitution and find the greatest liberal and conservative scholars, judges, and thought leaders in America exploring areas of agreement and disagreement about every aspect of the constitution. There’s the weekly podcast I host, We the People, which brings together liberals and conservatives to talk about constitutional issues in the news and throughout history, Constitution 101 classes for learners of all ages, and primary source documents, which are so crucial in learning and spreading light. So it’s just so meaningful to work at the Constitution Center and to offer up all these great free resources. And it’s great to meet your listeners and to be part of their quest for self-improvement.

Brett McKay: Well, Jeffrey Rosen, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Jeffrey Rosen: Thank you.

Brett McKay: My guest here was Jeffrey Rosen. He’s the author of the book, The Pursuit of Happiness. It’s available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find more information about his work at his website, constitutioncenter.org. Also check out our show notes at aom.is/pursuitofhappiness, where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM Podcast. Make sure to check out our website at artofmanliness.com where you can find our podcast archives, as well as thousands of articles that we’ve written over the years about pretty much anything you think of. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate it if you’d take one minute to give this review on Apple Podcasts or Spotify. It helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you think will get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay reminding you to not only listen to AOM Podcasts, but put what you’ve heard into action.