The United States currently finds itself in a rancorous political moment, with partisan name-calling on the one hand and much hand-wringing about the classless nature of the debate on the other. Those in the latter camp seem to think that politics has devolved from an unspecified golden age in which politicians sipped tea and talked about their issues with solemn decorum.

In truth, politics has always been a rowdy arena, and if one looks to our founding period for a bastion of politeness, they will not find it there.

Men in public life called each other, not just the traditional ‘liar,’ ‘poltroon,’ ‘coward,’ and ‘puppy,’ but also ‘fornicator,’ ‘madman,’ and ‘bastard;’ they accused each other of incest, treason, and consorting with the devil. —Gentlemen’s Blood: A History of Dueling

Political tensions ran especially high in the 19th century because men found it difficult to separate political disagreement from personal insults:

In our early years a man’s political opinions were inseparable from the self, from personal character and reputation, and as central to his honor as a seventeenth-century Frenchman’s courage was to his. He called his opinions “principles,” and he was willing, almost eager, to die or to kill for them. Joanne B. Freeman, in Affairs of Honor, writes that dueling politcos ‘were men of public duty and private ambition who identified so closely with their public roles that they often could not distinguish between their identity as gentlemen and their status as political leaders. Longtime political opponents almost expected duels, for there was no way that constant opposition to a man’s political career could leave his personal identity unaffected.’ —Gentlemen’s Blood

Refusing a challenge to duel would effectively end a man’s political career. Dueling proved to a man’s constituents that he had the requisite honor, courage, and leadership to represent them in Washington.

And thus you had governors and legislators, Congressman and judges squaring off not through bumper stickers and robo-calls, but on the field of honor. Here are a few of the most famous of these single combats in American history.

3 Famous Duels That Actually Occurred

The Burr-Hamilton Duel

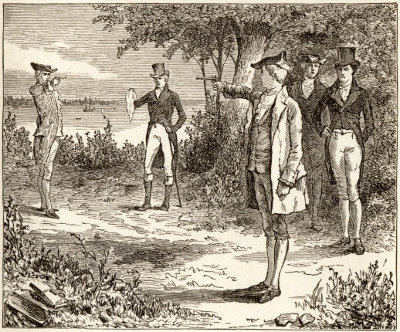

The most famous duel in American history is unquestionably that which occurred between Vice President Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton, who greatly influenced the founding of America’s economy and was possibly on track to become President himself. Burr and Hamilton had long been political enemies by the time they met on the field of honor. Hamilton had been instrumental in preventing Burr from winning the Presidency when Burr tied Thomas Jefferson’s vote count, leading to Burr’s eventual appointment as VP. The two men continued to square off politically until rumors that Hamilton had been saying “despicable” things about Burr led the slandered veep to issue a formal challenge to duel.

The two men met on the field of honor in Weehawken, New Jersey on the morning of July 11, 1804. Interestingly enough, Hamilton’s son had fallen to a mortal blow in a duel at the very same place just two years before. The same guns used in his duel were also used in his father’s.

The accounts of precisely what happened are conflicting, but it is generally thought that Hamilton fired first, aiming high and missing Burr completely. Burr then aimed squarely at Hamilton’s torso and returned fire. Hamilton fell, the bullet lodged in his spine, and he died the following morning.

Whether Hamilton’s miss was intentional or not is debatable. Hamilton had recorded in a letter the previous night that he intended to purposefully miss Burr in an effort to end the confrontation without bloodshed. Still, other believe that Hamilton so detested Burr that he shared this sentiment simply to paint Burr as the villainous shedder of innocent blood, thus forever besmirching his character.

If that truly was his wish, it was certainly granted. Though murder charges were levied against Burr, he was never brought to trial. But the ensuing political fallout undermined Burr’s political clout and brought a swift end to his career.

The Jackson-Dickinson Duel

Prior to his presidential career, Andrew Jackson was known for his inclination to invoke violence in defense of his honor; he was the veteran of at least 13 duels. These showdowns left his body so filled with lead that people said he “rattled like a bag of marbles.”

The most famous of Jackson’s affairs of honor was his confrontation with prominent duelist Charles Dickinson. Dickinson, rumored to be the best shot in the country, had insulted the future President by alleging that he cheated in a horse racing bet between Jackson and Dickinson’s father-in-law. Insults were exchanged, culminating with Dickinson insulting Jackson’s wife. Slandering Jackson’s wife was “like sinning against the Holy Ghost: unpardonable.” Biographer James Parton claimed that Jackson “kept pistols in perfect condition for thirty-seven years” to use whenever someone “dared breathe her name except in honor.” Jackson had no choice but to issue a challenge to duel.

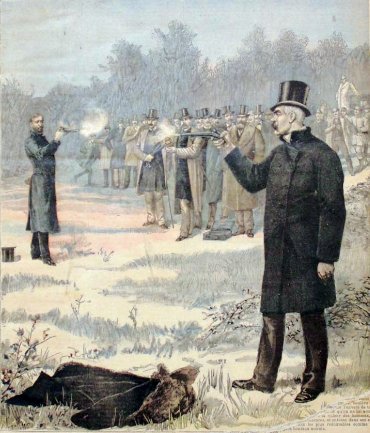

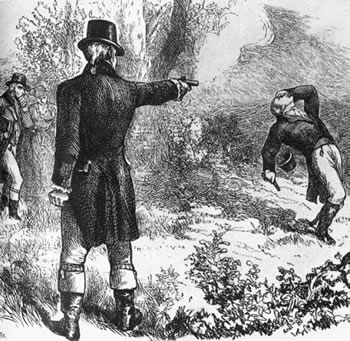

Jackson and Dickinson met at Harrison’s Mill on the Red River in Kentucky on May 30, 1806. The men were to stand at eight paces and then turn and fire. Dickinson was a well-known sharpshooter and Jackson felt his only chance to kill him would be to allow himself enough time to take an accurate shot. Thus he calmly allowed Dickinson to fire into his chest. The bullet lodged in his ribs, but Jackson hardly quivered, calmly leveling his pistol at Dickinson. But when the trigger was pulled the hammer of his gun only fell to the half-cocked position and did not fire. According to dueling etiquette, this should have been the end of the duel. Jackson, however, was not finished with Dickinson. Re-cocking his pistol, he aimed and fired, striking Dickinson dead.

It was only then that Jackson took heed of the fact that blood was dripping into his boot. Dickinson’s musket ball was too close to his heart to be removed and forever remained lodged in Jackson’s chest. The wound would lend him a perpetual hacking cough, cause him persistent pain, and compound the many health problems that would beleaguer him throughout life. But Jackson never regretted the decision. “If he had shot me through the brain, sir, I should still have killed him,” he said.

The Clay-Randolph Duel

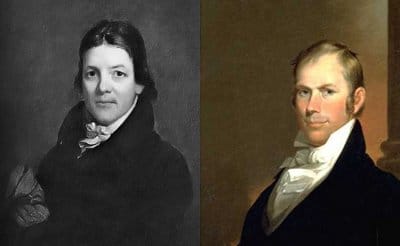

John Randolph was quite a character. He fought his first duel at 18, seriously wounding a fellow student over his mispronunciation of a word. His volatility continued as a Congressman; “he called Daniel Webster “a vile slanderer,” President Adams a “traitor,” and Edward Livingston “the most contemptible and degraded of beings, whom no man ought to touch, unless with a pair of tongs.” When he wasn’t hurling insults at his associates, he was challenging them to duels.

Following a slanderous speech on the Senate floor in which he accused sitting Secretary of State Henry Clay of “crucifying the Constitution and cheating at cards,” Senator John Randolph found himself the recipient of a formal challenge to duel. While comfortable with assailing the man’s character, Randolph, an experienced marksman, had no intention of robbing Clay’s family of their patriarch (and suffering the political fallout of slaying the Secretary of State). Several days before the duel took place, Randolph confided in Senator Thomas Hart Benton that he was unwilling to kill Clay, but did not want to sacrifice his personal honor either, so he would instead purposefully aim high when the time came to fire.

When the day of the duel arrived on April 8, 1826, both men met on the field of honor. As preparations for the start of the duel were still being made, Randolph accidentally fired his gun, which was pointed at the ground. Clay accepted that the misfire was an accident and allowed the duel to proceed. Marching the agreed upon number of steps in opposite directions, both men turned and fired. Randolph, apparently motivated by the humiliation of his misfire (and his missed chance to come off as the magnanimous one), made no effort to aim high, although he still just missed his intended target, the bullet perforating Clay’s coat. Clay also missed, and having gained no satisfaction, demanded another go around. This time Clay missed again, and Randolph followed through on his promise to Benton by firing into the air. Moved by the sentiment, Randolph met Clay at midfield for a handshake to end the duel, noting to his opponent that he owed him a new coat. Clay simply replied “I am glad the debt is no greater.”

A Couple of Close Calls

Not every challenge to duel ended with gunfire. Here are a couple of noteworthy near misses.

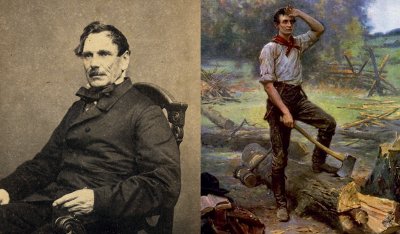

The Lincoln-Shields Duel

As an elected official in the Illinois State Legislature, future President Abraham Lincoln was sharply critical of James Shields’ performance as Illinois State Auditor. Lincoln even resorted to adopting various pseudonyms and publishing many satirical letters criticizing Shields (a common tactic at the time). In an unfortunate twist of fate, Lincoln’s future wife Mary Todd and a friend also wrote several letters. But the women got carried away, changing the tone from satirical criticism to insult. Shields, upon discovering that Lincoln was behind the letters in one form or another, issued an immediate challenge. Lincoln, unwilling to accept the public disgrace that came with refusing a duel, and eager to impress his future wife Mary, accepted.

As the challenged party, Lincoln set the parameters for the duel. It was to be fought with large cavalry broadswords in a deep pit divided by a board which no man could step over. In creating such parameters, Lincoln aimed to disarm his opponent using his superior reach advantage and avoid bloodshed on either side. Furthermore, Lincoln hoped that such ridiculous conditions would force Shields’ withdrawal. But initially, they did not.

On September 22, 1842, the two men met on the field of honor. As the seconds desperately tried to sway Shields’ determination, he looked over and saw Lincoln chopping at the branches of a nearby tree that would be far out of his own reach. Realizing that he was outmatched, Shields agreed to attempt to talk it out with Lincoln. Lincoln’s second convinced Shields that Lincoln had not written the letters, and Lincoln offered an apology for the misunderstanding, which Shields fortunately accepted. Shields went on to become a prominent United States Senator, and Abraham Lincoln went on to become, well, Abraham Lincoln.

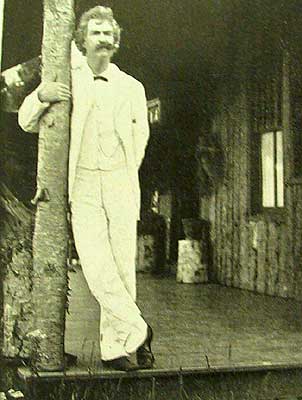

The Twain-Laird Duel

Finally, we end in a duel that neither came to fruition nor is invested with any great historical significance. But it is quite funny.

While living in Virginia City, Nevada, sharp-witted satirist Mark Twain was up to his usual pot stirring, writing such outrageous editorials for The Territorial Enterprise that locals dubbed him “The Incorrigible.” When Twain wrote a piece erroneously accusing a rival paper, The Virginia City Union, of reneging on a promised pledge to charity, the publisher of the paper, James Laird, made such a stink over the false accusation that Twain challenged him to a duel. Twain’s second, Steve Gillis, took Twain to practice his shooting, only to find that the man’s pen was truly mightier than his pistol; Twain couldn’t hit the side of a barn. Filled with fear, Twain collapsed. As Laird and his men were making their way over, Gillis grabbed a bird, shot his head off, and stood admiring the corpse. Laird’s second asked, “Who did that?” and Gillis responded that Twain had shot the bird’s head off from a good distance and was capable of doing it with every shot. Then he gravely intoned, “You don’t want to fight that man. It’s just like suicide. You better settle this thing, now.” The creative ploy worked, and the men reconciled. Tom Sawyer would have been proud.

If you missed it, read part 1 of this series: An Affair of Honor – The Duel