If you were like most boys, you probably went through a karate phase as a kid. When I went through my karate phase as a 5- and 6-year-old, I demanded that my family called me “Daniel-san.” Unfortunately, they did not comply.

There’s one man you can thank for your karate phase: Bruce Lee.

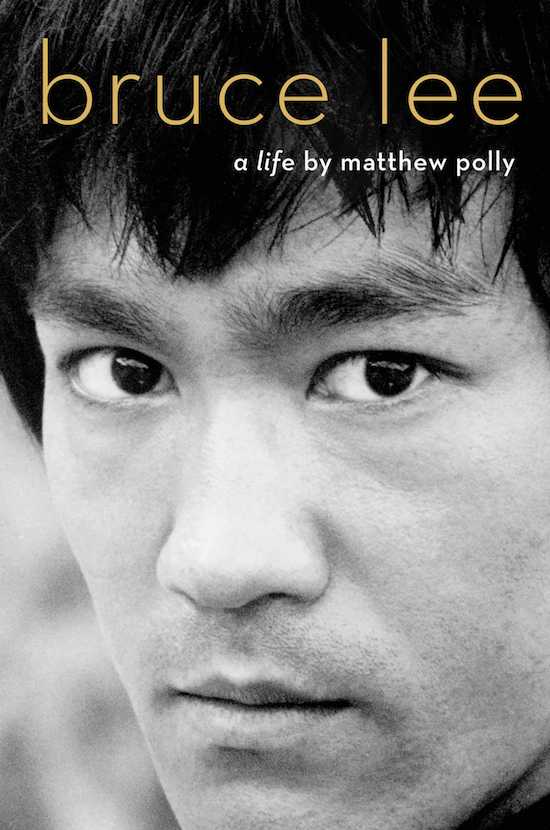

As my guest will show us today, Bruce Lee nearly single-handedly popularized martial arts in America thanks to his breakout Hong Kong kung fu movies in the early 1970s. My guest’s name is Matthew Polly and he’s the author of the new definitive biography of Bruce Lee called Bruce Lee: A Life.

Today on the show, Matthew and I explore the creation of the legend that is Bruce Lee, starting with his unique family history that had him straddling Eastern and Western cultures his entire life. Matthew gives us vignettes into Lee’s early life that show his fire, scrappiness, and love of martial arts, including his rise as a child star in Hong Kong and his love of street brawling. We then discuss how Lee started formal kung fu training as a teenager and how his ambition caused him to bump heads with his teachers. Matthew then shares how coming to America helped Lee refine and reinvent his martial arts practice, how Lee got his break in Hollywood, and how he ended up teaching kung fu to movie stars like Steve McQueen and James Coburn. Along the way, Matthew shares details of Lee’s relentless fitness routine and talks about Lee’s personal library of over 2,500 books that included a lot of philosophy and psychology. We end our conversation discussing Lee’s legacy and how he changed not only cinema, but our idea of manhood in America.

Show Highlights

- Why is there such a dearth of Bruce Lee biographies out there?

- Lee’s interesting familial makeup

- Lee’s lifelong East-West struggle and straddling

- His early life as a child star in Hong Kong

- The street fighting prowess (and style) of Bruce Lee, and the rooftop fights of Hong Kong

- Why Lee had to keep his kung fu training a secret

- How Lee ended up in Seattle, and his early experiences in America

- Bruce Lee, cha-cha king and kung fu instructor

- Lee’s big dreams for his life

- The true acting and martial arts genius of Bruce Lee

- Lee’s obsession with physical fitness/training — lifting weights, taking supplements, etc.

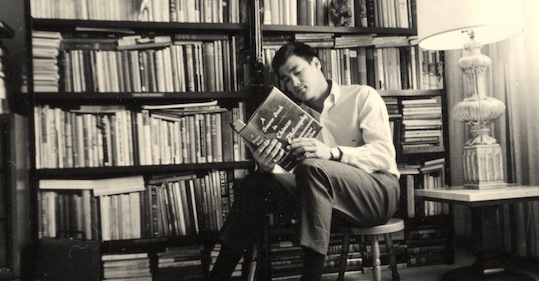

- Lee’s voracious reading habits and voluminous library

- How Lee’s reading influenced his kung fu

- Some of Lee’s famous kung fu students in Hollywood

- The ups and down of Lee’s acting career

- How Lee’s movies changed American cinema and culture

- Some of the life lessons Matt took away while writing the book

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- Enter the Dragon

- The Big Boss

- Japanese occupation of Hong Kong in WWII

- Bruce’s father, Lee Hoi-chuen

- How film critics reviewed Bruce Lee’s movies in his time

- Wing chun

- Ip Man

- Ruby Chow

- Jesse Glover (Lee’s first student)

- Linda Lee (Bruce’s wife)

- the one-inch punch

- The Green Hornet

- Jeet Kune Do

Connect With Matt

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Wrangler. Whether you ride a bike, a bronc, or a skateboard, Wrangler jeans are for you. Visit wrangler.com.

Saxx Underwear. Everything you didn’t know you needed in a pair of underwear. Get $5 off plus FREE shipping on your first purchase when you use the code “AOM” at checkout.

Starbucks Doubleshot. The refrigerated, energy coffee drink to get you from point A to point done. Available in six delicious flavors. Find it at your local convenience store.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Recorded with ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. If you’re like most boys, you probably went through a karate phase as a kid. When I went through my phase as a five and six-year-old, I demanded that my family call me Daniel-San ’cause Karate Kid was my favorite movie. Was also going through a Top Gun, Goonies, and Ghostbusters phase at the same time so the full name was Daniel-San Mikey Maverick Peter Venkman. My family did not comply with that demand.

Anyways, if you went through a karate phase, you got one man to thank for that. It’s Bruce Lee. My guest will show us today Bruce Lee nearly single-handedly popularized martial arts in America thanks to his break out Hong Kong, kung fu movies in the early 1970’s. My guest’s name is Matthew Polly, he is the author of a new definitive biography of Bruce Lee called “Bruce Lee: A Life.”

Today on the show, Matthew and I explore the creation of the legend that is Bruce Lee starting with his unique family history that had him straddling Eastern and Western cultures his entire life. Matthew then gives us vignettes into Lee’s early life that shows his fire, scrappiness, and love of martial arts, including his rise as a child star in Hong Kong and his love of street brawling.

We then discuss how Lee started formal training and kung fu as a teenager and how his ambition caused him to bump heads with his teachers. Matthew then shares how coming to America helped Lee refine and reinvent his martial arts practice, how Lee got his big break in Hollywood, and how he ended up teaching kung fu to movie stars like Steve McQueen and James Coburn. Along the way Matthew shares Lee’s relentless fitness routine, talks about Lee’s personal library of over 2,500 books that included a lot of philosophy and psychology. We enter a conversation discussing Lee’s legacy and how he changed not only cinema but our idea of manhood in America.

After the show’s over, check out the show notes at aom.is/brucelee.

Matthew Polly, welcome to the show.

Matthew Polly: Thanks so much for having me on, Brett.

Brett McKay: You got a new biography out about a man who I would say had just a huge impact on not only American cinema but also Asian cinema and because it’s the Art Of Manliness podcast I would say he had a huge influence on American masculinity as well as Chinese masculinity and I’m talking of course about Bruce Lee. Like every other red-blooded, American boy, I went through a karate phase when I was in elementary school, watched the kung fu movies Bruce Lee did during the 60s and 70s.

He’s always been a big part of my idea of what it means to be a man. The guy who can kick butt no matter whatever situation he finds himself in. It’s about a year ago I was like, “Okay, I want to do a podcast about Bruce Lee. Let’s go look for some Bruce Lee biographies. There’s got to be a ton out there ’cause this guy, of course, changed cinema as we know it.” But, I was surprised by the dearth of biographies about Bruce Lee. What do you think is going on there? Why hasn’t there been that much written about his life and his career?

Matthew Polly: I was shocked as well because Bruce Lee was one of my childhood heroes. I’d read all the martial arts magazines, but I hadn’t really looked at the biographies and when I researched it, there was only one still in print. It was written 25 years ago and it was pretty poorly researched. That’s one of the reasons I felt compelled to write the book.

I think the reasons are two-fold. One, I think it matters that he’s Asian American. We know as pretty much any white guy does anything gets at least half a dozen biographies. Steve Mcqueen has six. James Dean has nearly a dozen. Also, that Bruce was into kung fu which I think is looked down as low brow. If he’d been a painter I think he would have gotten at least a couple good ones.

I think those two factors meant that Bruce, in a weird way, got overlooked. Everyone knows who he is but no one thought he was a serious enough figure to be treated with the kind of respect you need to have for someone to write a 500 or 600-page biography.

Brett McKay: You saw there was a need and you were like, “I’m the guy to fill this need.” I’m glad you did ’cause the biography’s fantastic. I couldn’t put it down. Let’s talk about Lee because, as you said, he’s Asian American. A lot of people think he’s just Asian. He’s just from Hong Kong, but he’s got an interesting background.

One of the things he struggled with, you say struggle, throughout his entire life, is he straddled two worlds. He straddled East and he straddled the West. That straddling, it started even before Bruce Lee was born. Tell us about his family history and how it shaped or may have contributed to how he perceived the world and how he experienced the world.

Matthew Polly: One of the revelations that I came up with in my research was that his background was far more diverse than we had previously known. Everyone who was into Bruce Lee knew he was part Eurasian, that he had a European ancestry, but they thought his grandfather was German Catholic. What I discovered was actually his great-grandfather was Dutch Jewish. A man named Mozes Hartog Bosman, who in the 1850s traveled to Hong Kong, bought a Chinese concubine, and had six kids. Those kids became the richest men in Hong Kong.

Bruce Lee’s grandfather, whose name was Ho Kam Tong, was so wealthy he had 13 concubines and then had an affair with a British woman. That was Bruce Lee’s grandmother. So, Bruce Lee was part Hun Chinese, part Dutch Jewish, and part English. Growing up … Well, first he was born in America, which a lot of people don’t know. His father was an actor who was on tour. He returned to Hong Kong when he was about five months old.

In Hong Kong, he faced discrimination because he wasn’t pure Chinese. Then, when he returned to America when he was 18, he faced discrimination because he was Asian, not white. His whole life was spent being proud of who he was in context in which he was discriminated against. I think that’s part of the reason he was so interested and so successful at bridging the divide between the East and West.

Brett McKay: A lot of people don’t know about this about Bruce Lee is that his acting career began way before he did any of his kung fu movies. He was actually a child star in Hong Kong, I think when he was four or five or six right?

Matthew Polly: Yeah. His father was an actor, so he came from an entertainment family. The first film he showed up in he was two months old. It was filmed in San Francisco whenever he was born and he just appeared on screen. Actually, it was a cross-dressing performance. He played a little girl. Excuse me. His acting career began in earnest when he was six years old and he appeared in nearly 20 films as a child actor up until he was 18. What’s interesting is none of those were kung fu movies.

Brett McKay: He’s was known as, “The Little Dragon.”

Matthew Polly: That’s right. That was his stage name, Li Xiao Long, is how they pronounce it in Mandarin. It’s an appropriate one because of course, Bruce Lee was a fire element. He had a short temper. He was very fiery. He was hyperactive, but yes he was called “The Little Dragon” and that became his symbol and why later he wanted to name his movies, Enter The Dragon because that’s who he was.

Brett McKay: That’s who he was. Well, yeah, you’ve mentioned he’s fiery because I thought that was another interesting aspect of Bruce Lee because this is a guy, Hong Kong, not technically part of China, it was still part of the … under British rule, but Chinese where the culture is typically conformist, emphasis on community. But, you have Bruce Lee here who was very individualistic, more than his siblings, more than his dad. Where did he get that sense of individualism despite growing up in a culture that shunned it?

Matthew Polly: Some aspects of his personality, I think, are just a mystery. Each child gets born with their own soul and, I think, Bruce from the very start was highly individualistic. But, there are certain things that influenced him when he was young. One thing I thought was fascinating is that he nearly died during the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong during World War II. There was a cholera epidemic and he had to fight from the very earliest years of his life just to live. That kind of fighter spirit, I think, infused him for the rest of his life.

Another factor I think was crucial and was underplayed in most Bruce Lee biographies because the family is embarrassed about it, but his father became an opium addict. That it was very common for Chinese opera stars, which his father was, to smoke opium, but in Bruce’s teenage years, the addiction got its claws into his father. I think that affected Bruce greatly and caused him to distrust authority on a certain level because he didn’t trust his father or he had complicated feelings towards his father.

Bruce, from a very early age, refused to accept anyone imposing authority on him. One of the stories, the revaluations in the book is that he was kicked out of this prestigious parochial school he went to called La Salle. For years, no one would admit what really happened, but I ended up talking to some of his classmates in Hong Kong and what turned out that happened was first, he pulled a knife on his P.E. teacher who had struck him and then later, he did a prank on one of his classmates that upset everyone and he got kicked out of school.

So, he really was the kind of hyperactive, troublemaking kid in the back of a class that couldn’t sit still and never did his studies. Was considered a terrible student and his true love was street fighting. From a very early age, he was a pugnacious, rebellious kid.

Brett McKay: Yeah, the street fighting thing was interesting because Bruce Lee’s dad was an actor. He grew up in a relatively affluent … He had an affluent life growing up. Family had servants. He was able to go to these prestigious parochial schools, but the guy loved to fight. Somehow he always ended up the leader of these gangs, which is interesting because you typically think, “Okay, if you’re poor and you come from a rough neighborhood, okay, you end up in a gang because it’s supplying you some sort of sense of security that you’re not getting at home.” That makes sense to us, but it’s like why would this upper-middle-class kid start street gangs so he could just beat the crap out of people?

Matthew Polly: Yes. That was fascinating about him. One, that he came from an affluent background. That’s sort of downplayed. His story, they like to do a rags-to-riches and that’s true when he got to America because his parents cut him off. So, in America, he started at the very bottom, but in Hong Kong, he was at the top. His mother’s family was one of the richest in Hong Kong. His father did very well in real estate and was also a famous actor. So, he had a very affluent upbringing.

I think one of the things I had to get my head around is when we think of Hong Kong, we think of modern Hong Kong which is basically this high-end shopping mall. But, when Bruce was growing up in the 1950s, it was basically a refugee camp run by British businessmen. There were millions and millions of Chinese refugees fleeing the war, the revolution in China and so the streets were an actually dangerous place to be. There were triads, there were gangs. The police were extremely corrupt. There was a lot of gang activity and I think Bruce in his middle-class way was imitating what was going on around him.

Brett McKay: Yeah. The thing that I got a chuckle out of, talking about some of these gangs made up of 10-year-olds and they had knuckle dusters, switchblade knives, and chains. I’m like, “Geez Louise.” My son is seven. I couldn’t imagine him keeping a pair of brass knuckles in his pocket just in case he gets in a fight at school.

Matthew Polly: Exactly. My son’s three and the idea that he has a razor blades stuck in his shoe to use in a fight … it’s a completely different era and I often thought of West Side Story. The Jets and the Sharks, they would go meet and Bruce would go fight with the British kids across town because there was this Chinese British rivalry in the colony.

Brett McKay: Yeah, yeah. There was a lot of that going on. So, let’s talk about his fighting during his street gang years. At this point, he wasn’t really doing kung fu or any type of martial art, he was just punching and kicking and doing whatever. There was no method, right?

Matthew Polly: Yeah. So, Bruce Lee just was a tough kid and one of the other things that was hard to get my head around is you think of Hong Kong and you just think kung fu everywhere, but at the time kung fu was sort of a low, not very respected thing. It wasn’t until he met a classmate or a friend of his names William Cheung who was much better as a fight than Bruce. This drove Bruce crazy ’cause he was a perfectionist and he always wanted to be the best and he wanted to be a leader. This idea that there was this older, bigger kid who was better than him kind of drove him crazy and he wanted to figure out how to be better than William Cheung.

It turned out, William Cheung studied Wing Chun kung fu under the tutelage of the master Ip Man who’s now famous for all of these movies from Hong Kong. So, Bruce only took up Wing Chun to be a better street fighter and to be better than this kid, William Cheung, who it drove him crazy was a better fighter than him.

Brett McKay: This is about when he was 15 years old, right?

Matthew Polly: Yeah, 15, 16. Yeah.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about kung fu ’cause it’s become a catch-all phrase. At the time, it seemed like it was used as a catch-all phrase for pretty much any martial art. You see this when Bruce Lee comes to America and he’s teaching people. People used karate interchangeably with kung fu, but there is a difference. What is kung fu? What separates it from say taekwondo or karate and then after that specifically what was Wing Chun and how is it different from other types of kung fu?

Matthew Polly: Right. So, the way I would think about it the martial arts describes all sort of fighting styles that have a formalized structure where they teach you certain ways to punch or to kick or to throw or to grapple. Boxing can be a form of martial arts. Then, each nation had its own particular type. So, taekwondo is a Korean art form. Karate is a Japanese art form and kung fu was the term the Chinese used for all their different types of martial arts.

Then, within kung fu then there’s the specific styles. So, China has hundreds. You can go on for an entire podcast discussing them. Wing Chun was one style of Southern kung fu and it was actually kind of small and obscure. There were only a couple masters in Hong Kong. There were styles like Hung Ga, who had a far bigger following, but Wing Chun became popular in Hong Kong because its students were particularly good at challenge fights and they would go out and challenge stylists from other kung fu styles. They would win a lot of these fights. If you were a brash street fighter like Bruce Lee and you wanted to be better at it, Wing Chun was the style that you would study.

Brett McKay: Right. Wing Chun was supposedly, according to legend, started by a female monk, right?

Matthew Polly: That’s right. So, every Chinese kung fu style has a legendary story where its origins came from. It’s almost always highly fictionalized, but it tells you a little bit about what they think the style is about. So, Wing Chun is unique because its founder was supposedly a Shaolin nun who had developed the style by making it better for women in the sense of close in contact, low kicks, and focusing on if you were someone who was smaller than your opponent. Since Bruce Lee actually grew up smaller and frailer than his siblings, and his classmates because he nearly died in that cholera epidemic, it was the perfect style for him.

Brett McKay: I imagine because kung fu was looked down upon, he had to keep this as a secret, didn’t tell his parents he was taking kung fu lessons.

Matthew Polly: That’s right. His parents throughout his life were trying to figure out ways to get him on the straight and narrow. It was one of those situations I think is familiar to a lot of families. His older brother, Peter, was the studious ‘A’ student who his father favored and Bruce was the young rebellious troublemaker.

So, Peter was the one they were saving tuition money for and Bruce was the one they were saving bail money for. I thought it was fascinating that Bruce, even though he was rebellious, there was a certain base level of respect he had for his parents. He would hide things from them that he knew would get him in trouble. So, he never told them he was studying Wing Chun until they finally found out and then they blew up and there was a huge argument about it.

Bruce said to his father, kind of hurt, “I’m not a good student, but I’m good at fighting. I’m going to use fighting to make a name for himself.” Of course, at 16 he couldn’t realize that he could eventually become the most famous unarmed martial artist to ever live, but even from an early age, he had this sort of idea that this is the one thing I’m good at. He spent the rest of his life figuring out a way to fit that into society.

Brett McKay: You talked about Bruce had a natural disposition to be individualistic. Kung fu in Chinese martial arts, big on tradition, big on structure, big on rigidity ’cause it derived out of Confucianism where there’s ritual and you do things in a certain way because that’s just the way you do them. Did Bruce Lee bristle at his kung fu instruction? Were there already things like he would just pop off to his instructor or did he respect the process?

Matthew Polly: Well, he wasn’t respectful in this sense. One of the first questions he asked his teacher … Ip Man was his master and Wong Shun Leung was the guy who taught the daily sort of beginners class that Bruce was in. The first thing he asked him was, “How long will it be until I’m better than you?” His instructor, in recalling this, has this great phrase. He said, “He asked too much.” You can just imagine your teaching this punk sort of teenage kid martial arts and he doesn’t know anything and the first thing he wants to know is how long before I can kick your butt?

So, Bruce was pugnacious from a very early age, but I think at the beginning stages he knew so little that he was willing to learn the pattern. He was willing to learn what they taught him, but very quickly, within a few years, he started to branch out and bring other elements into kung fu besides just Wing Chun.

Brett McKay: Did it make him a better fighter, like a better street fighter, like he started winning more of these duels? I thought that was interesting. I didn’t know that went on in Hong Kong where people would be like, “I challenge you to a fight.” You’d have to do it. Did that help him at all?

Matthew Polly: Yeah, that’s a fascinating aspect of Hong Kong culture at that time. It doesn’t go on anymore, but they would go onto the rooftops because there was so little space. That was the only place they could get privacy.

It did make him a better fighter and it didn’t calm him down at first. What he would do is go into the streets and go … One of his stunts was he would wear really traditional clothing in Westernized Hong Kong and if someone looked at him funny or said something about the clothing he was wearing, he would start a fight with them. That’s what eventually got him kicked out of Hong Kong, is he started so many street fights with random strangers that the police came around to his mother and said, “If you don’t calm him down, we’re going to throw him in jail.”

Brett McKay: All right, so this is a man, a young guy who had a chip on his shoulder, man to be reckoned with. Yeah, he finally gets kicked out of Hong Kong. His parents were fed up with him. He got kicked out of school. Doing kung fu and they finally decided, “You’re out. You’re going back to America. You’re going to Washington.” Why Washington? Why did he end up there and what happened to Lee? Did that have an effect on him? Did it turn him around at all?

Matthew Polly: Yeah, it had a profound effect. The reason he went to Washington was because his father had a friend who owned a restaurant in Seattle. So, the Chinese community, it’s always a friend of a friend because they’re living in America where they’re being discriminated against. Like all immigrant communities, they ban together for mutual support.

Bruce was sent to Ruby Chow’s restaurant in Seattle and he was expecting to be treated like an honored guest, but his father was so angry and felt he had been spoiled growing up ’cause his father grew up very poor and he felt like he has this kind of rich son who didn’t respect anything. So, he told Ruby Chow to treat him like a wash boy, a busboy. So, Bruce got stuck in a closet, essentially a converted closet under the staircase, and was forced to do the most menial tasks.

As we mentioned earlier, he was a childhood actor. He never held a real job. He went to night schools. He had an affluent background. He had servants in the household. He never had to wash a dish in his life. So, he’s 18. He’s all alone. He’s in America and he’s washing dishes and he’s thinking, “This could be my future. I might never get out of this restaurant.”

So, that experience worked. He literally was scared straight and it focused his ambition and competitiveness to dream of what he could do to make it I America. In many ways, Bruce’s story is the classic immigrant success story of a young boy who had a troubled past who comes to America and finds his way here.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that moment he decides he’s going to become a doctor. Which is … He didn’t do well in school. I think he wrote his brother or his friend back home in Hong Kong and was like, “Here’s my plan. What do I need to do to … Exactly what do I need to do to become a doctor in five years?”

Matthew Polly: That’s right.

Brett McKay: It was really funny. So, he goes back to school and he gets pretty studious. He buckles down. Does he continue to practice kung fu or do any street fighting or did he leave that behind him for a bit?

Matthew Polly: Well, one of the things we hadn’t talked about was that he was also a dancer and he was cha-cha champion of Hong Kong. So, the first thing he did in America was he taught dance to other overseas Chinese. So, that was his first real job other than washing dishes in the restaurant for his room and board, but at every dance performance he would, sort of in the middle of it, show off some of his kung fu.

Some of the Chinese community, the students who were learning dance from him, were amazed by his incredible Wing Chun talent. They hadn’t seen anything like that before. So, he quickly realized that he could make at least a part-time job out of teaching kung fu and he quickly gathered a group of sort of street toughs from the school he was at, Edison Technical High School in Seattle. His first student was Jesse Glover, an African American and so Bruce Lee was the first kung fu instructor to ever teach a black student, which was a real racial breakthrough because, at the time, the Chinese community and the black community were at odds.

He slowly expanded from Jesse to the point where he had maybe a dozen young students learning Wing Chun kung fu from him. Once he got to college, his dream was to become the Ray Croc of kung fu, that is the guy who founded McDonald’s. He was going to franchise kung fu schools across the country. So, he had this very entrepreneurial spirit from a very early age.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that bit about him being the cha-cha king was interesting because the people that he danced with would say that Bruce could just look at one move and immediately put it into action, which goes to show the guy probably had an innate talent for body awareness, space awareness. He had that talent. He knew how to move his body unlike me who I’m very clunky and I would step on people’s toes if they were to teach me a cha-cha move.

Matthew Polly: That’s right. Bruce Lee’s image is someone who became this incredible martial artist through sheer force of will and that’s partly true. He trained tremendously. He was absolutely obsessed about the martial arts, but he also had a certain sort of genius and that was … I think his girlfriend in college, Amy Sanbo, said that he was a kinetic genius. He could look at a move and just figure out how to do it immediately.

She was a ballet dancer and he could of a pirouette within a couple tries. So, that was Bruce’s great gift is that anything physical he was able to do quite quickly and that gave him this tremendous advantage in the martial arts, particularly learning new martial arts. I’m sure we’ll get to, but one of the things that Bruce is known for is incorporating a lot of different styles into one. Only someone who’s really gifted at learning other styles quickly could have done that.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I thought that was an interesting point. You talk about when he starts teaching kung fu to some of his fellow students at the technical high school. It was very informal. They’d meet in a parking lot or in a park somewhere. And, the way you describe it, it wasn’t really Bruce teaching them, like, “I’m the teacher. Bow to me. Respect me.” It was more like Bruce was actually … He was using them to refine his martial art and these guys that were there, they learned some things along the way. Really Bruce was using this sort of very informal kung fu school that he had as an incubator for himself to refine and melding different types of martial arts. Jesse Glover, I think he had a boxing background, correct?

Matthew Polly: That’s right. Yeah, Jesse was boxing and judo and a lot of these guys were street toughs and so there were a number of amateur boxers. They did judo. What’s interesting about Bruce is he had adapted to the environments that he was in and so I joke that if he had gone to Russia, he would have been the best at Russian martial arts. But, he went to America where boxing and wrestling were the two main forms of sports combat.

So, he quickly started to pick up things that his students knew and that’s one of his great gifts is he didn’t come and just say, “I have the perfect system. Let me just give it to you.” He would look at what they did and go, “Oh, that’s nice. I like that. Why don’t I figure out a way to work that in.” One of the complaints of the students were, is he teaching us or is he actually just using us to make himself better?

He was in part doing both and one of the things I always try to remember when I was writing about Bruce, is that at this point and time, he’s 19 years old. When I was 19, I was pretty self-centered and only interested in my own development. I think Bruce was like that in his early years, so he was more like the gang leader and he had this kind of gang of kung fu students/followers. They would meet together and he would show them some moves, but then get them to spare together so he could make himself better.

In those early years, his primary goal was he wanted to be the best martial artist in the world and they were there to help him as opposed to the other way around.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that was another common theme throughout Bruce Lee’s life, these big ambitious goals he set for himself. It’s like, “I’m going to be the best in the entire world.” Later on, we get to the studio, he’s like, “Well, I’m going to be bigger than Steve McQueen.” The guy just had ambition.

Matthew Polly: Yeah, I think that’s one of the things I sort of admire most about Bruce is that most people get to America from another country and they’re just thinking, “How can I survive?” There’s all these stories of people who are doctors in Iran and they’re driving a cab and then their dream is that their children will do better.

Bruce didn’t want to wait around. He wasn’t going to wait for the next generation to make it in America. As soon as he landed, he was like, “I’m going to be the biggest kung fu instructor in America. I’m going to have schools all over the country and I’m going to be the best martial artist the world’s ever seen.” Then, as you mentioned, when he got a break in Hollywood, he didn’t just think, “I’d like to be a working actor who gets parts here and there.” He was like, “I want to be the biggest movie star in the entire world,” as an Asian guy in 1960s Hollywood, which was completely impossible because Asians barely could get any parts on TV let alone a starring role in a movie. Bruce had an innate self-confidence that’s, in a way, staggering when you look back at it.

Brett McKay: Right. So, these kung fu schools, like he had one going on, that’s where he met his wife, Linda, correct?

Matthew Polly: That’s right. He had given a lecture at the high school where Linda attended and she had noticed him because he’s a handsome guy. He was a flashy dresser. She thought he was kind of big-city … He reminded her of the star of West Side Story. Because she immediately had a crush on him she went and found the kung fu school where he was teaching at the time and became one of his students. She was really sort of a disciple of Bruce’s before they started dating.

Brett McKay: We have this other aspect and we’ll get into this too, Bruce, he was a ladies man. What was surprising at the time during the 50s and 60s, this is a time when there was interracial dating or relationships was looked down upon. It didn’t matter. All women, whether they were from Hong Kong or from Washington, there was something about him that was attractive.

Matthew Polly: That’s right. Bruce had game.

Brett McKay: He did.

Matthew Polly: He was a child actor. He had a tremendous amount of charisma and so, while his brother was the introverted, studious one, Bruce was the life of the party. He was the extroverted, troublemaker and I think that a lot of charisma is a sense of danger and he carried that with him. That kind of excited the coeds around.

So, he never had a problem getting a date. He always dated beautiful sort of flashy girls until he met Linda. She was much more serious and thoughtful than the typical girls that he dated. Yeah, he was a ladies man. He really was.

Brett McKay: So, he started these kung fu schools. In the process too, he also marries Linda because she gets pregnant and that was a big ordeal because her family was dead set against her being married to an Asian-American, but Linda says, “No, I love him. We’re going to do this.”

That’s the other thing. Linda really seemed to believe … As you said, she was a disciple before she was Bruce’s wife. She really believed in what Bruce as doing.

Matthew Polly: I think that’s the most crucial thing to their relationship and what allowed Bruce to have the confidence to succeed during periods when everyone else was telling him it wasn’t going to work, was that Linda was his rock and she believed in him in this almost religious way. She just worshiped him.

She thought she was lucky to get him and that’s fascinating because, as you mentioned, her parents were dead set against it. People forget, but interracial marriage was sort of the gay marriage of that period. It was illegal in 17 states in America for members of two different races to marry. And, it wasn’t until 1967 that the Supreme Court outlawed what they called anti-miscegenation laws.

So, her family, Linda knew her mother wouldn’t approve and she kept Bruce Lee a secret for nearly a year. It wasn’t until she got pregnant and they tried to elope and then got caught. Then, there was this big family pow-wow where they tried to convince her not to marry this Chinese guy, but she was very adamant. She loved him absolutely and I think that was the key to his success later in life is that he had this sort of rock of support and admiration and belief.

Brett McKay: Not only was he a Chinese guy, he was a Chinese guy trying to be a kung fu teacher and they’re like, “What is kung fu?”

Matthew Polly: Yeah.

Brett McKay: It’s like, I’m going to be an Instagram influencer. What in the world? How are you going to support my daughter being an Instagram influencer?

Matthew Polly: That’s right. We forget about it, but no one in America outside of Chinatowns knew the word kung fu. The Chinese community was very small and very isolated and they didn’t interact that much with the white community. So, almost nothing was known about Chinese culture in American in the 1960s.

When they asked him, one of Linda’s uncles asked him, “What are you going to do to support my niece?” and he said, ” I teach kung fu,” and the guy goes, “What?” Same thing. Instagram, at least people knew. It was like I’m going to teach her blah blah blah. He just made up a word. They thought not only had she gotten pregnant by a non-white guy, but she was going to marry somebody who was going to be destitute his whole life.

Brett McKay: All right, so he tries to do this kung fu thing. He starts opening up different schools and it didn’t really pan out. He spread himself too thin. He couldn’t pay the rent. How did he get back into the acting game in America? ‘Cause as you said at the time, during this time there weren’t a lot of parts for Asians. If Hollywood needed an Asian, they typically would take a white person and paint their skin and make their eyes look … Do makeup so they look Chinese. They wouldn’t actually hire an Asian. So, how did Bruce get back into it? How did he think, “Yeah, this is going to be the thing. I’m going to drop teaching kung fu and I’m going to become a kung fu star?”

Matthew Polly: It’s an amazing story. One of the things that I think to understand Bruce is to understand that he was an actor first and foremost. So, even when he was teaching kung fu, his favorite thing to do was to go around giving kung fu demonstrations and he gave them all up and down the West Coast.

That was his great skill is to get on stage, do kung fu, and I felt it was like a standup comic, sort of working his routine and creating a persona. During these years when he was teaching kung fu, he was also really creating this persona of Bruce Lee the kung fu master.

Inevitably, someone noticed. When he was in Long Beach in 1964 at a karate tournament, he was noticed by someone who recommended him to a TV producer by the name of William Dozier. William Dozier wanted to do a Charlie Chan TV series and actually, the radical idea he had was to actually cast an Asian for an Asian part instead of doing the yellow face of casting a white actor and putting him in makeup.

He offered Bruce Lee the lead role in an American TV show, which would have been unheard of. It would have been a complete and total breakthrough and so Bruce was immediately onboard with his tremendous self-confidence. He believed that right out of the gate he was going to be a TV star.

Brett McKay: I think it’s an interesting point to make. He was an actor first, but again, I think some people dismissed Bruce Lee as a martial artist thinking, “Well, he was just an actor,” but the guy was actually … He had chops. He was impressive.

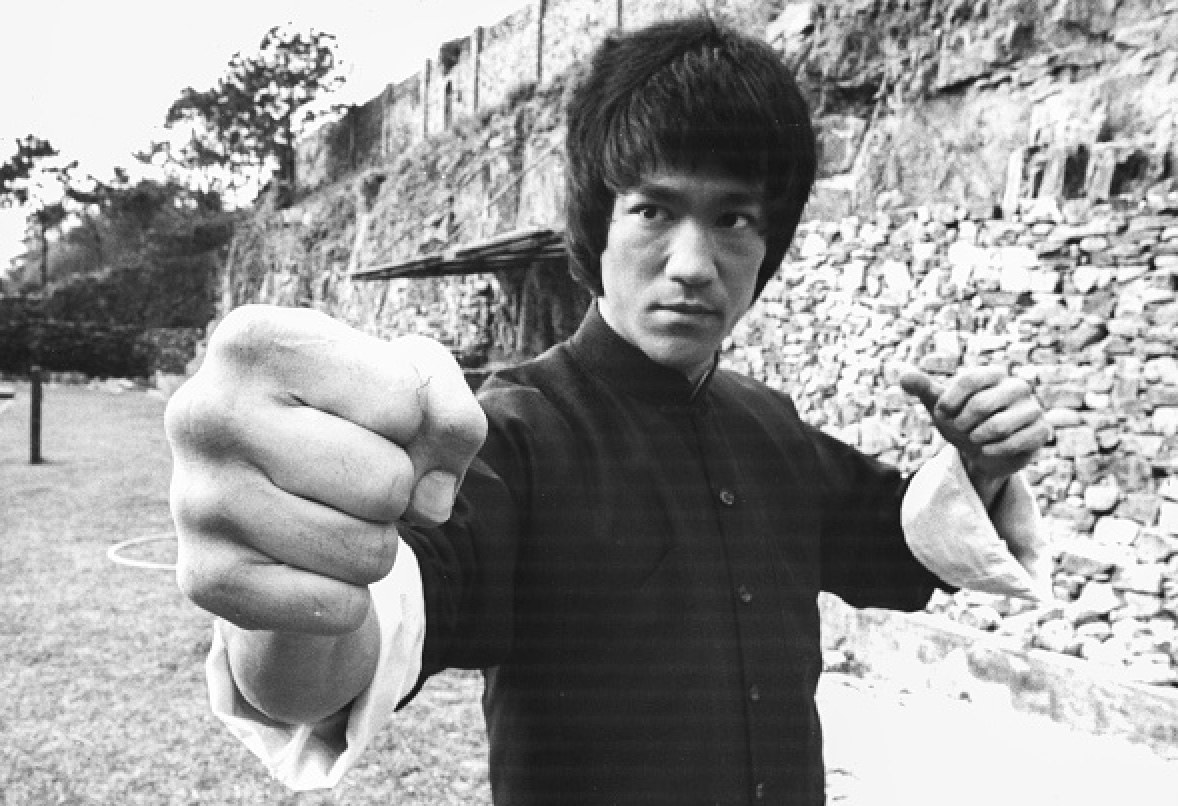

He was doing the one-inch punch that he’s made famous for where he just put his fist an inch away from someone’s chest and then just knock them over a chair. He’d do the fingertip pushup, like the one-finger pushup. He was an actual … He could fight. That was another big takeaway I got from this. It wasn’t just an act. He was the real deal.

Matthew Polly: That’s right. That’s important to state, which is when I make the argument that he was an actor first, I’m speaking kind of chronologically and psychologically, but he was the real deal. He was a genius and that’s why, I think, he’s irreplaceable because you have martial artists, great martial artists who try to be actors or movie stars, but they’re not very good actors. And, you have actors who try to be action stars, but they’re not very good martial artists.

Bruce Lee is one of the few people to be a genius at both. He was a very good actor and he was an unbelievable martial artist and those two abilities that he merged are why we still remember him.

Brett McKay: As you said, he got on the radar in Hollywood and that didn’t work out, but he landed a part with a TV show, The Green Hornet, where he plated Kato. How did that role change the trajectory of his career in Hollywood?

Matthew Polly: Dozier tried to get Charlie Chan’s Number One Son off the ground with Bruce Lee as a star, but it was immediately rejected by TV executives because no one in 1966 thought the American public would accept a Chinese hero on TV. So, Dozier pitched him his second show, which was The Green Hornet. Bruce got knocked down from being the star of the show to being the sidekick playing Kato to the Green Hornet, played by Van Williams.

At first, Bruce was quite upset that he had been demoted, but Dozier convinced him that this was a real opportunity to show the American public real Asian martial arts, which they’d never seen before. That’s another thing that’s hard to remember. There had never been a TV show with a character who was doing actually Asian martial arts on it. It was all the kind of John Wayne punch thing that you saw on TV.

So, Bruce had this chance to show off what he could do and he quickly became more popular than the main character. He got more fan letters and he was really embraced by the very small martial arts community of the time because one of their own had finally gotten on TV to show off their stuff. This set Bruce on the path to becoming a martial arts star by getting this first role playing Kato who was the karate master of the Green Hornet.

Brett McKay: Right. The Green Hornet ended. It didn’t do too well. It had that really bad cross-over with Batman and Robin. When you were describing it, I started laughing because I was like, “That sounds like just a terrible combination there.” Anyways, so yeah, as we were talking about, he starts … Acting’s on the radar again. As you were saying, he’s the real deal. Bruce has this innate talent for physicality, but he amplified it or magnified it by training all the time.

This was another sort of innovation Bruce Lee made. He was big on personal fitness, physical fitness. At the time, in the 60s, lifting weights, taking supplements … Today, it’s very natural, of course, everyone … It’s very mainstream, but at the time, only weirdos did that sort of stuff. Bruce, very early on, embraced physical training. Tell us about his physical training and his physical fitness routines.

Matthew Polly: Yeah, so that’s an important point, which is even the NFL didn’t allow its players to lift weights in the 1960s ’cause they believed it was damaging to an athlete. That’s how sort of different the attitudes were at that period. Martial artists never did anything except do their martial arts.

He was the first person to realize that to be the best martial artist possible, you also had to be strong and fast and in shape. The best way to do that was to specialize your training for that. So, he looked at it and he looked around at what was available. From boxing, he picked up road work. In the mornings he would go out for like three or four-mile runs and he also jumped rope.

Then, he also was, as you said, early into the weightlifting craze. He had all the muscle and fitness magazines of that period and he would buy the supplements that they were selling for his diet. He also had friends give him sort of weightlifting equipment. Every couple days, he would go through a weightlifting routine and jog and run. He trained like a modern athlete long before modern athletes were training like that. In that area, he was extremely innovative.

Brett McKay: Yeah, he got shredded. That’s how he had that … He fought with his shirt off in the movies and he looks jacked and shredded.

Matthew Polly: That’s right. I think he recognized two things. One, what was interesting about Bruce is that he realized very quickly that for the martial arts, you don’t want to be too bulky. All those weightlifting magazines at the time were about size. You wanted to have the huge, puffy muscles and he realized that those slow you down. Speed is what kills when you’re fighting. A quick punch is much more important than a heavy arm throwing it.

Bruce wanted to be slick and slim and shredded and ripped. Then, of course, he was also acting at the time and I think he recognized that for years, for decades, centuries even, Chinese males were portrayed as kind of weaklings and that if he wanted to create this image of a masculine, super-powered, super-heroic, Chinese male character on screen, changing his musculature would be one way to do that in such a visual medium.

Being completely ripped and shredded would convey this power on screen. So, he had two goals. I think, during this period, you can see him pursuing both goals at the same time. He still wants to be the greatest martial artist on Earth and he also wants to be the biggest star on Earth. Whenever he could find a way to do both at the same time, he was happy.

Brett McKay: Right. Another component to his self-improvement during this time, not only was he training hard and exercising, he also, a lot of people don’t know this about Bruce Lee, he was a voracious reader. He didn’t just read dumb books, he was reading Saint Augustine. He was reading Plato. He was reading pretty heavy, philosophical works. What was going on there with Bruce’s reading?

Matthew Polly: Yeah, I think that’s one of the reasons he’s endured is because he wasn’t just a meathead. He just wasn’t some boxer guy who can pound people. He studied philosophy at the University of Washington. He was a college student. He fell in love with philosophy and psychology and also some of the self-help books of that era

His library, he had over 2,500 books, which we know he read very intensely because he has margin notes everywhere. He would write down quotes that he liked from the various authors. He read voraciously, a lot about martial arts, but also Descartes, Hume, Aquinas on the Western side and then he would read Laozi, Zhuangzi, Confucius, Mencius, and the various Chinese scholars and philosophers.

He was thinking about everything he was doing physically and he was an amazing way able to kind of combine the two that most people don’t. You either have the eggheads or the meatheads and Bruce was both.

Brett McKay: I thought what was interesting too was that his reading influenced his martial arts and allowed him to start creating what became known as Jeet Kune Do, which was Lee’s version and he incorporated a lot of what he read to develop. How would you describe Jeet Kune Do? It seems like it’s more of a philosophy towards martial arts and not necessarily a system of movements. Would that be right?

Matthew Polly: I think that’s what he came to. Initially, he was trying to find a better version than what he felt he had from Wing Chun. That was from he had a famous fight with Wong Jack Man that he won, but it didn’t go very well and he was frustrated. He thought he should have won it very quickly and it took a long time and it was sloppy.

So, he had been, for years, working out with these American students who were good at other types of combat sports as we said like boxing and judo, and Bruce started to think about ways to create what he considered would be the ultimate martial arts style. The three things he combined were the kicking from kung fu and the footwork and punching from boxing, but then he added a unique element that no one’s ever done before. He added Western fencing.

His brother was a fencer and had showed him fencing, then, this gets back to his studies, loved reading fencing books because they were highly technical and they were all about these various sort of specific techniques. So, Jeet Kune Do was really sort of unarmed fencing. That’s the way he thought about it at the time, but then after a while, he philosophically began to believe that no style should be formalized.

What he began to preach was that Jeet Kune Do was just a phrase and what it means is to essentially find your own best style and that you shouldn’t be attached to any one system ’cause then you become mechanized and like a robot. Fighting is a fluid thing. You’re always in this moment where you’re going back and forth. If you’re attached to a specific set of movements, you can be easily defeated. That was Bruce’s ultimate message.

Brett McKay: Right. He was the grandfather of mixed martial arts. Take whatever you can and make it work for the situation.

Matthew Polly: That’s right. That’s where you see his Americanness. As you said earlier, it’s sort of Chinese culture was very much attached to tradition and so when you listen to a traditional martial artist and you ask him what you study, he’ll tell you who his master was, who his master’s master was, and the whole lineage. What’s important is that you kept the tradition pure.

Bruce’s approach was totally pragmatic. It was like, “If that works, that’s great. It doesn’t matter if it’s Korean or it’s Japanese or we got it from Brazil. We don’t care where it came from. All we care is that it works in a fight,” and that’s very much what’S become the spirit of MMA, which is mixed martial arts. It doesn’t matter who taught you that punch or where it came from. Did it work in the fight? Did you win or did you lose? That’s all we care about.

Brett McKay: So, during this time he was developing his new type of martial art. It’s a style without a style, I think is how he described it, or a system without a system. He was working with some big karate guys here in American like Chuck Norris, but then he got hooked up becoming a kung fu teacher to some big stars like Steve McQueen, we mentioned. Was is James Coburn was the other one? Yeah, as the other big one, big disciple. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was a student of his.

How did that change Bruce’s career ’cause I imagine being with these guys gave him more of an itch, more of a desire to become a big movie star?

Matthew Polly: Yeah, so when the Green Hornet got canceled after one season, he was in LA with a wife and a young son and he couldn’t pay the rent. He needed to figure a way to do that and what he had learned early on from his experiments with becoming a kung fu instructor, is that teaching kung fu is a hard business because most of the students don’t have that much money. There weren’t that many. People weren’t interested in Asian martial arts at the time, so you couldn’t get a lot of students.

He realized the way he could do this and survive was to teach private lessons to celebrities for an extraordinary amount of money. He has these celebrity students paying him the equivalent of about $800 an hour for private kung fu or at that time Jeet Kune Do lessons with Bruce Lee.

He had two goals in doing it. One was just purely monetary. These lessons allowed him to support his family. But, the second goal was to learn from them how they had become a star and also to use those relationships to advance his own acting career. I think it’s crucial to understanding Bruce’s success later to know that he was essentially a disciple of Steve McQueen and James Coburn.

At the same time, he was also their teacher. He was learning from them as much as they were learning from him and he was learning how do you make it in Hollywood, how do you be a star, how do you conduct yourself, how do you dress, what kind of car do you drive, how do you interact with the directors. In many ways, he went to sort of film school through these private lessons.

Brett McKay: Yeah, the lesson was from Steve McQueen, just be cool. Got to cool, man.

Matthew Polly: That’s right. And, he learned how to be cool from Steve McQueen, how to dress, how to conduct himself, how to interact with women. When he got back to Hong Kong, the people were like, “We’ve never seen anything like this.” That’s because he had spent several years at Steve McQueen’s feet going, “How does this guy do this?”

Brett McKay: Yeah, I want to be cool like Steve McQueen. Everyone wants to be cool like Steve McQueen. So, that’s interesting. He’s in America, but his career … He didn’t become a star in America. He had to go back to Hong Kong. How did that happen? You’d think he came to America, he’d be done with Hong Kong, but why did he end up in Hong Kong and why was that the thing that made him catapult into worldwide fame?

Matthew Polly: After the Kato … Sorry, the Green Hornet in which he played Kato was canceled, he was extremely frustrated because, for the next four years, all he could get was one bit part every eight months on some terrible TV show. He played the karate instructor on some terrible sitcom or he had a bit part in a crappy Western. Those, A, weren’t paying the bills, but B, weren’t advancing his career. He had moved backwards.

What little fame he had gained playing Kato was quickly dissipating to the point where no one knew who he was outside the industry. He was extraordinarily frustrated and he was given an opportunity to go back to Hong Kong and make a movie. The reason why that happened was the American studios released The Green Hornet in Hong Kong and they renamed it the Kato show. So, Bruce was the star of the show in Hong Kong because he was a hometown boy who’d gone off to Hollywood, which was like the magical kingdom and succeeded as far as they could tell.

They had no idea that he couldn’t pay his mortgage and he was struggling. All they saw was, “My God, one of us had actually gotten on an American TV show,” which in 1960s, never happened. It was like, if you were from Botswana and you were the one kid who succeeded, everyone in Botswana would be like, “My God, we’ve made it. We’re in Hollywood.” Bruce was that guy.

They offered him a chance to be in a really low-budget kung fu movie and Bruce wasn’t certain he should do this because he thought the movie probably would be terrible, no one would see it, and it wouldn’t advance his career at all, but he needed the money. He had bought a fancy house in Bel Air and he couldn’t afford the mortgage. So, he went to Hong Kong purely for the cash and then remarkably, the movie he made called The Big Boss, became the biggest box office sensation in Southeast Asian history and Bruce, immediately overnight, became bigger than the Beatles, the biggest star anyone had ever seen. That completely transformed his career trajectory.

Brett McKay: When did those films start crossing over to America?

Matthew Polly: So, those films weren’t released to America until almost right a few months before he died in 1973. What’s interesting about Bruce is his fame outside of Southeast Asia where he was huge, was entirely posthumous because outside of Southeast Asia, no one really knew who he was.

The Big Boss, Fist of Fury, Way of the Dragon, the three Hong Kong movies he made and then Enter the Dragon, which was his Hong Kong/Hollywood co-production, were all released in 1973.

Brett McKay: How did these films change cinema, not only in Hong Kong and America … What was different about these movies that made them so huge?

Matthew Polly: Well, one factor, obviously, is that it had Bruce Lee and Bruce Lee, when you watch his earlier performances, you can see the talent, but he’s not quite a star yet. It’s that undefinable thing. But, by the time he’s in The Big Boss, you just can’t take your eyes off of him. He’s absolutely magnetic. These were the first movies in which you saw a genius at work.

The second factor was nobody in the West had ever watched a Hong Kong movie outside of Chinatown. There was three white guys who would go to Chinatown and watch it and then the Chinese community would watch them, but no one else did. I compare the Hong Kong film industry in the early 1970s to the Nigerian one today, which was very popular within that geographic area amongst that community, but no exposure outside of it.

His movies transformed the world because they introduced the Western culture to what was going on in Chinese cinema.

Brett McKay: As you said, these movies didn’t become really popular until after he died, but they had a lasting impact on American cinema because martial arts movie became a thing and a lot of the stuntmen that worked with Bruce Lee went on to make a lot of popular crossover … They were filmed in Hong Kong, but they aired in America. Jackie Chan is a great example of that. Chuck Norris trained with Bruce Lee. The guy was Walker Texas Ranger. The best Chuck Norris movie was Sidekicks though I got to say.

Matthew Polly: You like sidekicks?

Brett McKay: Of course.

Matthew Polly: I’m a Lone Wolf McCoy guy, but I’ll give you Sidekicks.

Brett McKay: Right. But, it changed American cinema. That became a genre in America after Bruce Lee.

Matthew Polly: It changed American cinema I think in several fundamental ways. One, it brought all this Asian talent over. So, you mentioned Jackie Chan. Jackie Chan was a stunt boy on two of Bruce’s films. You can see him for like a fraction of a second in Enter the Dragon when Bruce snaps his neck. Jackie learned at Bruce’s feet and after Bruce died, they tried to make Jackie the next Bruce Lee and then he realized it would work better if he played a kind of comedic, clown role.

Chuck Norris as well. So, all of this talent that came after Bruce introduced to the world through his movies. It introduced an entirely new genre to the West. Karate, kung fu movies were big in China, but no one had seen them in the West. Suddenly, we had this genre that you later see with the Matrix or Kill Bill of John Wick is a great example of a kind of modern kung fu classic.

The third way I think is crucial, is it totally changed fight choreography. If you go back and you watch 1960s Star Trek, you can see Captain Kirk throwing his bolo, haymaker, John Wayne punch out of right field, missing the guy by three feet and the guy collapses. That was considered acceptable fight choreography. You can’t watch a show today where it’s an action hero, he’s not a martial arts master.

Tom Cruise is kicking and punching and doing jujitsu moves. Batman, Christopher Nolan’s Batman is this kung fu master. Sherlock Holmes, that recent movie. Sherlock Holmes is a kung fu master. So, it completely changed action cinema in the West and that was, I think, probably the deepest impact Hong Kong films and Bruce Lee had.

Brett McKay: Besides impacting America cinema, Bruce Lee, through his movies, impacted American culture. As you said, in the 60s, no one knew hardly anything about Asian martial arts. If you said kung fu, it was like, “Kung what? What is that?” Because of Bruce Lee, now there’s dojos in pretty much every single town in America.

Matthew Polly: That’s right. That why I was shocked that there wasn’t a good biography about Bruce Lee. I think that’s because his image is just this kung fu movie guy who made a couple low-budget films. But, if you think about it, he completely transformed American culture. All these parents in the suburbs whose six-year-old sons are learning Taekwondo are only doing that because of Bruce Lee. No one was doing that back in 1961. The kung fu craze is totally the result of the popularity of Bruce Lee and his films.

Afterwards, millions and millions of young Westerns like myself took up the martial arts. It spread, all the dojos in every small town … There’s a quote in the book from Fred Weintraub who produced Enter the Dragon and he said, “Before Bruce Lee, every small town had a barber shop and a beauty parlor. After Bruce Lee, it also had a karate studio with a poster of Bruce Lee on the wall.”

All of these kind of strip mall dojos that you see today are part of Bruce Lee’s contribution to the world. What’s interesting about him personally is that was his goal. It wasn’t an accident. He set out like a missionary to use the medium of film in order to spread Asian culture to the West. His impact was self-conscious and incredible. That’s why I think he’s an important cultural figure and not just a celebrity.

Brett McKay: So, there’s a lot more we could dig into. We talk about his family life which was complex.

Matthew Polly: Yes.

Brett McKay: There’s also his death. Bruce Lee, he died a young man. He was only 32 and because he died young like a lot of people that die young, there’s a lot of legends around his death. He’s basically kind of like Tupac or Elvis. Some people think he’s still alive, but you, it looks like you’ve uncovered how Bruce Lee really died.

We’ll let people buy the book to find that out, but before we end, I’m curious, after writing … This is a big tome of a book. Were there any life lessons you took away after researching and writing about Bruce Lee?

Matthew Polly: It’s interesting because Bruce Lee influenced my early life, got me into martial arts. I wanted to be like Bruce Lee physically, but as I was working on the book, he influenced me on a kind of emotional level I would say. Very specifically, this book took seven years to write. It was incredibly hard to do. It was only supposed to take 18 months or two years so the advance money ran out. I was living on paycheck to paycheck, just trying to survive.

Brett McKay: You’re like Bruce Lee.

Matthew Polly: Exactly. I’m writing about Bruce Lee starving in Hollywood and I’m starving here trying to write the book about Bruce Lee starving in Hollywood. The way it inspired me was that you should never give up. If you’ve got a dream and the thing that you really love … This is clichéd, but Bruce Lee proves that the impossible is possible if you’re willing to pay the ultimate price.

He did something by becoming the first Chinese-American male actor to ever stare in a Hollywood movie that no one had ever done before and no one at the time, even his closest friends, thought he could do. The only reason he achieved that is because he would not quit. When they told him no, he just got angrier and kept at it.

For me, that was the lesson I held onto which was when I thought I couldn’t finish this and it wasn’t going to work, I just kept at it ’cause I was like, “If Bruce Lee can become the first star, I can finish this biography.” I think that’s a lesson we can all hold to our hearts when times are tough.

Brett McKay: Did you write an affirmation like Bruce Lee did? We didn’t talk about that. I thought that was interesting too.

Matthew Polly: No, we didn’t.

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Matthew Polly: Yeah. His affirmation. He did a lot of self-help stuff from Napoleon Hill and his affirmation was, “I’m going to be the biggest,” used the term Oriental, “superstar the world has ever seen and make $10,000,000,” and just over the top sort of affirmation. No, I didn’t do that affirmation, but I kept it in my heart that I wasn’t going to quit on Bruce Lee ’cause he wouldn’t have given up.

Brett McKay: That’s right. Well, Matthew, this has been a great conversation. Thank you so much for your time. It’s been an absolute pleasure.

Matthew Polly: Thank you, Brett. This was a lot of fun.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Matthew Polly. He’s the author of the book “Bruce Lee: A life.” It’s available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. Check out his website mattpolly.com for more information about his work. Also, check out our show notes at aom.is/brucelee where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure you check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com and if you enjoyed the show, you’ve got something out of it, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give a review on iTunes or Stitcher. Helps out a lot.

As always, thank you for your continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.