Editor’s note: This is a guest post by Tony Valdes.

Welcome back to our series on Greek mythology. In the last post we defined what a myth is and examined the pantheon of Greek gods and goddesses. Today we will leave the lofty heights of Olympus and come down to the mortal world.

Don’t forget, we’re headed towards some ideas for application at the end of the series. That being said, remember that the goal here is not to delve into every detail and variation, but rather to paint with broad strokes to get the big picture.

The Creation of Man

Now that the Olympians were enthroned atop Mount Olympus, the human race could make its debut. The following two myths offer an explanation of how mankind was brought into being.

Version #1 – Metal Men

In this version, the Olympians themselves created men out of metal, starting with gold. These men were upright and perfect. With each generation the gods decreased the quality of the metal, which increased the amount of wickedness men were capable of. The final generation of men was made of iron. One day Zeus will no longer be able to tolerate the wickedness of mankind and will wipe them from the earth once and for all.

Version #2 – The Gift of Prometheus

In the more common Greek creation myth, Zeus put Prometheus and his brother Epimetheus in charge of creating men and animals. In his enthusiasm, Epimetheus gave all the best gifts to animals. Prometheus knew that men would not survive long without any advantage over the beasts, so he compensated by creating men in the image of the gods. In The Greek Myths, Robin Waterfield takes this a step further and describes it as Prometheus’ own essence and intelligence. In addition, Prometheus stole fire from Olympus and gave it to men and tricked Zeus into accepting only the fat and bone of animals as sacrifices, thereby allowing mankind to keep the meat and skin for themselves. With these safeguards in place, Prometheus had ensured that mankind had the means to not only survive, but to thrive. Zeus’ fury was unfathomable; he condemned Prometheus by chaining the Titan to a rock and sending an eagle to tear out his liver. At night, Prometheus’ body would mend itself, which allowed the eagle to feed on him day after day for all eternity. The Greeks believed that the moaning of the wind was actually the agonizing cries of Prometheus as he endured the punishment of Zeus.

The First Woman

The previous myths pertain only to the creation of man. For the creation of woman there is the story of Pandora.

In each version of the Greek creation myth, Zeus had a motive to lash out against humanity. Zeus chose to take out his vengeance on man by creating the first woman, Pandora. She was made to be an irresistible beauty to men. In her book Mythology, Edith Hamilton describes Pandora as “a sweet and lovely thing to look upon, in the likeness of a shy maiden, and all the gods gave her gifts, silvery raiment and a broidered veil, a wonder to behold, and bright garlands of blooming flowers and a crown of gold – great beauty shone out from it” (88). But in addition to these lovely qualities, Zeus also gave her an insatiable curiosity. Before presenting Pandora to mankind, Zeus gave her a jar (later mistranslated as a box) filled with things like disease, pestilence, and sin. Naturally, Pandora’s curiosity got the better of her and she opened the jar, unleashing its horrors into the mortal world. Fortunately, Pandora was able to close the lid on the jar before hope was lost, thereby allowing humanity to limp along though history without completely succumbing to Zeus’ clever punishment.

Why Would the Gods Create Humanity?

Regardless of which myth you choose, the reason behind the creation of man is vague at best. Much of Greek mythology seems to support the idea that the gods’ interest in the human race was almost like a game. Waterfield explains it best, saying, “The gods were truly delighted with their new toys. Every aspect of life on earth came into existence on that day. Goodness was henceforth defined as whether the brief part danced by a creature on the earth’s stage was pleasing in the gods’ eyes. It amused the gods to remind their creatures, in various ways, who their masters were, and to test their goodness. Just when everything was going well, they would cause a flood, or earthquake, or famine, or personal disaster. And they devised more and more complex dances for their toys” (13). This seems like a grim outlook, but it helped the Greeks explain the difficulty, misfortune, and dumb luck that are common in life. It also sheds light on their myth of Pandora: she was both a blessing and curse — a perfect catalyst that would further ensure the survival of humanity and provide generation after generation of entertainment for Zeus and his fellow Olympians.

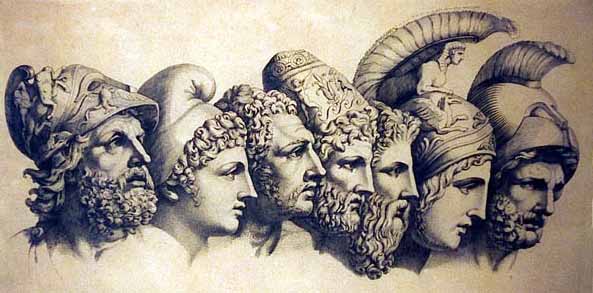

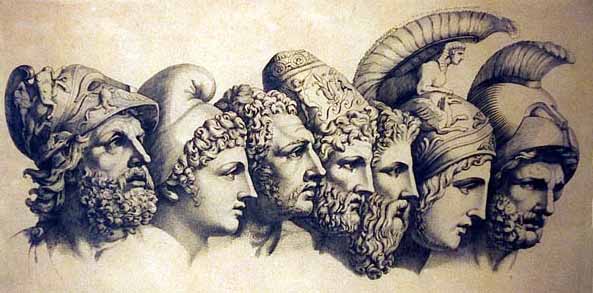

The Heroes of Ancient Greece

The terrors unleashed by Pandora’s jar left a bleak world for mankind to inhabit. Humanity was in desperate need of mighty men and women to inspire them. Thus the Greeks, like all cultures throughout history, were constantly looking for heroes — individuals who experienced the struggles and joys of human life but were also somehow greater than common men and women. The following five were the most revered among the Greek heroes.

Heracles (or Hercules)

The greatest of all the heroes of Greece was Heracles. His story is told by at least six famous Greek poets including Ovid, Euripides, and Sophocles. In the poet Apollodonus’ account the Theban prophet Tiresias says, “[Heracles] shall be the hero of all mankind.” He embodied all that the Greeks valued, namely courage and confidence. However, this son of Zeus and a mortal woman was also plagued by torments unlike any other.

Heracles was not overly intelligent, but he was passionate and impulsive; there was no better man to have as a friend, and no man more terrifying to have as an enemy. He was ruled by his emotions and plagued by outbursts of rage, which could be particularly lethal given that Heracles was the strongest man to ever live. According to the myths, only two things could overpower Heracles: supernatural forces and his own guilt.

Heracles might have been able to live a normal life had it not been for Hera, who desperately hated her son Heracles. He was a reminder of her husband’s unfaithfulness, which was a thorn in the side of the goddess of fidelity. Hera’s fury started when Heracles was an infant when she sent two assassins in the form of serpents to kill the child during the night. Heracles’ foster parents came in to the room and found the infant hero playing with the corpses of the snakes, which he had strangled to death when they entered his crib.

Hera’s diabolical vengeance finally came to fruition much later in the hero’s life. She recognized that Heracles’ weakness was found within his own emotions. She smote Heracles with temporary insanity, which caused him to beat his wife, Megara, and their three children to death with his bare hands. When Heracles was released from his insanity, he saw the bodies of his family and his bloodstained hands. The hero fell into despair and was determined to commit suicide. Quite a different tale than that presented in Disney’s animated Hercules, eh?

Heracles’ good friend and fellow hero Theseus was able to prevent him from taking his own life, but Heracles, overwhelmed by guilt and shame, was now a broken man. Hera, however, was not satisfied. She wanted to utterly destroy her husband’s illegitimate son. When Heracles arrived at the palace of the Mycenaean king seeking punishment for his horrible crime, Hera inspired the king to give Heracles twelve impossible tasks that would surely destroy the guilt-laden Heracles. These twelve tasks became known as The Twelve Labors. Waterfield gives tremendous detail regarding the Labors, but for our purposes here we will simply list the basics of each.

- Heracles fought the Nemean Lion and choked it to death with his bare hands.

- Heracles defeated the three-headed Hydra, who grew two more heads when one was chopped off.

- Heracles captured the elegant Cerynitian Stag after a full year of hunting it.

- Heracles hunted and captured a particularly destructive boar the size of a bull.

- Heracles solved the problem of King Augeus’ filthy and overcrowded stables by using his strength to divert two rivers, and employing this torrent of water to flush out the filth.

- With the help of Athena, Heracles defeated the Stymphalian Birds by making a tremendous racket to drive them from their nests, then shot them all down one-by-one with his mighty bow.

- The Cretan Bull was known for being fierce and untamable; Heracles, of course, tamed it.

- Heracles killed King Diomedes and then fought his man-eating horses and drove them away, thus rescuing the people of the kingdom.

- Heracles was charged with retrieving the golden girdle of Hippolyta, queen of the Amazons. After much confusion and the queen’s accidental death, he succeeded in his task.

- Geryon, a three-bodied brute, shepherded a flock of cattle. Heracles fought the monster and captured the cattle.

- Heracles was charged with retrieving the Golden Apples of Hesperides. Heracles recruited Atlas for help, and after tricking each other back and forth, our hero of course came away with the golden apples.

- Much to the dismay of both Hera and the king of Mycenae, Heracles had succeeded at eleven seemingly impossible tasks. They had to ensure that the final labor killed the hero, so they sent him to retrieve Cerberus, the vicious three-headed, dragon-tailed guard dog of the Underworld. Much to their surprise, Heracles emerged victorious and hefted the horrible beast above his head.

Mythology contains many more adventures of Heracles and Hera’s continued attempts to destroy him, but the Twelve Labors are by far the most enduring. The end of Heracles’ story sees the hero tortured by Hera to the point of death, but Zeus intervenes before Heracles’ soul can enter the Underworld. Zeus snatched his son up to Olympus and commanded Hera to end her vengeful feud against him. Heracles was then granted immortality among the gods, where he presumably found rest and peace.

Theseus

In stark contrast with Heracles, Theseus was no more than a mere mortal. He was the favorite hero of Athens not only because his father was a king there, but also because Theseus was “compassionate as he was brave and a man of great intellect as well as great bodily strength” (Hamilton 225). Theseus was also revered for addressing ordinary problems as well as extraordinary ones. Hamilton speaks to this when she says, “Greece rang with the praises of the young man who had cleared the land of these [common thieves]” (221). His utter humanity and his intelligence make him a sort of Batman to Heracles’ Superman. And like those two pillars of our modern mythology, these two heroes shared a sort of friendship; Theseus, as you will recall, supported Heracles in his darkest hour following the death of his family.

Although he went on many adventures, Theseus is best known for defeating the Minotaur. The Minotaur was a terrible monster – a large bull that walked upright like a man – who lived at the center of an impossible maze called the Labyrinth. Every nine years the citizens of Athens were forced to send seven young men and seven maidens to Minos, the king of Crete, so that the evil king would not burn Athens to the ground. These fourteen tributes would be cast into the Labyrinth were the Minotaur would devour them.

Theseus would not stand for this. To the dismay of his father, he volunteered himself as one of the young men to be sent to Crete. He told his father that he would slay the Minotaur and return home with white sails on his ship in place of the usual black sails.

When Theseus arrived in Crete, Minos’ daughter, Ariadne, fell in love with him and provided him with twine so that Theseus might leave a trail to navigate back out of the Labyrinth. When Theseus reached the center of the maze, he slew the Minotaur with his bare hands and used the twine trail to lead his people to freedom.

There are different accounts of Ariadne’s fate, but ultimately she does not make it back to Athens with Theseus. The hero also forgot his promise to his father and left the black sails raised; believing that his son had died at the hands of the Minotaur, Theseus’ father cast himself off of a cliff into the sea. Thus Theseus accidentally and tragically inherited his father’s throne.

Perseus

Perseus, like Hercules, was a demigod, meaning that his mother was a mortal woman and his father was Zeus. Yet unlike Hercules, Perseus was not persecuted by Hera, but rather by mortal men. Perseus’ grandfather cast out both his daughter and infant grandson after hearing a prophecy that the child would kill him. He placed them in a makeshift boat and cast both into the sea. They would have starved or drowned had Zeus not intervened. He allowed both the mother and child to be rescued by kindly fishermen. Later, when Perseus had matured into adulthood, his mother was courted by Polydectes, who decided he would prefer the young hero dead. He convinced Perseus to retrieve the head of Medusa, a Gorgon, as a wedding gift.

The Gorgons were a gruesome race of creatures with the upper body of a woman, the lower body of a large serpent, and hair made of writhing, venomous snakes. Looking directly at a Gorgon would turn any mortal to solid stone.

Fortunately for Perseus, Pallas Athena and Hermes intervened; Athena gave him a mirrored shield and Hermes gave him a powerful sword. In addition, Hermes helped Perseus win the favor of the Hyperboreans, who gifted the hero with winged sandals, a magical bag that would allow any object to fit comfortably inside, and a magic helmet that would render the wearer invisible. With these tools, Perseus was able to successfully battle Medusa, using the mirrored shield to look indirectly at her horrible visage and slay her. The mighty sword allowed him to decapitate the Gorgon and the winged shoes gave him a means to escape her lair.

On his way home, he intervened and rescued Andromeda, a beautiful princess who was to be sacrificed to a sea serpent. Perseus married Andromeda and returned home. There he discovered the corruption of his father-in-law and used the Gorgon head against him. He pulled the ghastly thing from his magic bag and turned Polydectes to stone.

Perseus’ grandfather, who had cast his daughter and grandchild into the sea in an attempt to save his own life, met his timely demise as well. The prophecy against him was fulfilled when Perseus, who was competing in a discus-throwing contest, accidentally hurled the disc into the audience. It slammed into his grandfather, killing him instantly.

Perseus is rare among the Greek heroes because he is one of the few to settle down after a lifetime of adventure with a wife, have children, and live — as far as we know — happily ever after.

Atalanta

One of the few female heroes in ancient Greece, Atalanta was a formidable huntress and athlete who could out-perform any man. Her story, like many Greek heroes, includes an element of tragedy: her father, who had hoped for a son, abandoned his child in the woods. Atalanta was raised by a she-bear and eventually adopted by kindly hunters. This forged Atalanta into a formidable heroine.

When the Calydonian Boar, a massive tusked beast, terrorized cities and slew hunter after hunter, it was Atalanta who felled the savage animal with her bow. Technically it was a young man named Meleager who dealt the boar its final blow, but Meleager loved Atalanta and let everyone know that she deserved more credit than he for stopping the beast.

Meleager was not the only man to notice Atalanta, however. Her reputation brought men from far and wide seeking her hand in marriage. Hamilton says, “It seems odd that a number of men wanted to marry her because she could hunt and shoot and wrestle, but it was so; she had a great many suitors. As a way of disposing of them easily and agreeably she declared that she would marry whoever could beat her in a footrace, knowing well that there was no such man alive” (248).

It wasn’t until a young man, Milanion, received help from Aphrodite that Atalanta met her match. Milanion received three irresistible golden apples from Aphrodite to distract Atalanta during the race. Milanion was a swift runner and he could keep stride with Atalanta, but any time she started to gain on him, he would toss one of the golden apples off to the side of the path. Atalanta would stop to pick up the apple, having to run faster to close the distance between her and Milanion afterward. When the second and then third apples were thrown, Atalanta could not close the gap and Milanion won the race by a matter of inches, thus winning Atalanta’s hand in marriage. The myth ends with the couple transforming into lions, which seems fitting for someone as fierce and independent as Atalanta.

Jason and the Argonauts

The story of the Greek adventurer Jason contains many elements that we recognize in our modern stories and fairytales. Jason’s father was one of the mighty kings of Greece, however his nephew, Pelias, usurped him. At this time Jason was still an infant and had been hidden safely away for fear of Pelias’ wrath against the rightful heir to the throne.

In exile Jason became a strapping young hero and eventually returned to reclaim his father’s kingdom. Pelias was shocked to see Jason saunter into the throne room, but Jason harbored no hatred towards his deceitful cousin. Jason told Pelias that he could keep all the wealth and spoils that had accumulated during his reign as long as he allowed Jason to return to the throne and rule. Pelias, reluctant to surrender his position as king, crafted a plot to eliminate Jason. He agreed to surrender the throne…but only after Jason had completed a dangerous adventure.

According to Pelias, Jason’s dead father had bid his son to retrieve a valuable treasure known as the Golden Fleece. He gathered the mightiest heroes and set sail in his ship, the Argo. Jason and his Argonauts braved many perils in their quest for the Fleece.

Along the way they fought a horde of Harpies — horrible winged beasts that leave a gut-wrenching stench in their wake strong enough to rot fresh food instantly. The Argo next navigated through the Clashing Rocks — a dangerous nautical obstacle — and snuck past the island of the Amazons.

Eventually Jason arrived at the gates of the Colchian king. The king welcomed the heroes and invited them to a feast, eager to know why they had traveled so far from their home. Jason explained his quest for the Golden Fleece to the king and, in return for the king giving him the Fleece, offered to do anything requested of him.

The king was secretly furious that these foreigners would dare to ask for this great treasure, but he refused to murder his guests in cold blood. So the devious king devised another plan to rid himself of the heroes. He told Jason that he would gladly give him the Fleece if the hero could accomplish a trial of courage to prove his worth. First, Jason would have to yoke two fire-breathing bulls and use them to plow a field.

Next, he would plant the teeth of a dragon into the freshly plowed field. When planted, the dragon teeth would sprout up into a group of bloodthirsty soldiers, which Jason would then defeat in combat.

Jason knew that no man could survive such a trial, but agreed to the king’s terms. Fortunately, the goddess Aphrodite had intervened and caused the king’s daughter, Medea, to fall in love with Jason. Medea was a powerful sorceress and concocted an ointment from the blood of Prometheus that would protect Jason.

The following day, Jason completed the fearsome tasks with the help of Medea’s ointment. The Colchian king was furious and began to plan a new way to kill Jason and the Argonauts. Medea, however, was so overcome with love for Jason that she snuck to his ship during the night and warned him of her father’s plans. She led Jason to the Fleece, which was guarded by a fearful serpent, and used her magic to lull the beast to sleep. Jason then took both the Fleece and Medea to his ship and set sail for Greece.

On their way home, Medea protected Jason and the Argonauts from many other dangers, such as the combined threats of Scylla – a six-headed dragon – and Charybdis – an enormous whirlpool that could consume a ship whole. When he arrived at Pelias’ throne room with the Fleece, he finally learned the full extent of his cousin’s treachery: Pelias had forced Jason’s father to kill himself and Jason’s mother had died of grief. Jason turned to Medea for help, who used her treachery and magic to concoct a horrible death for Pelias.

Now Jason took his rightful place on the throne and Medea, who had betrayed her father and left her home for Jason, looked forward to being at peace with the love of her life. Jason, however, had different plans: “All that [Medea] did of evil and of good was done for [Jason] alone, and in the end, all the reward she got was that he turned traitor to her” (Hamilton 175). After she had borne him two sons, Jason abandoned Medea and went to marry the daughter of the king of Corinth.

Medea used her magic to create a “wedding gift” — a beautiful robe doused in poisons and magic potions — for Jason’s new bride. As soon as Jason’s bride put the dress on, she was consumed by flames and died. Jason recognized Medea’s handiwork. He intended to kill her, but all he could do was curse her name as he watched her ride out of sight on a chariot drawn by dragons.

Today’s Wrap Up

Like cultures all through history, the Greeks were preoccupied with the origin of humanity, the explanation for human suffering, and heroes that could inspire them to rise above their circumstances.

Now that we’ve spent two posts establishing the Greek gods and the mortal world, we are ready to examine two of the most famous pieces of literature in the Western canon, which just happen to be portions of Greek mythology. In the next posts we will look at the story of the infamous Trojan War, and the life of Odysseus, king of Ithaca and all-around manly man.

Primer on Greek Mythology Series:

The Gods and Goddesses

The Mortal World and Its Heroes

The Trojan War

The Odyssey and Applying What We’ve Learned

____________________

Sources and Further Reading:

If you would like more than just the broad strokes presented here, there are some excellent resources to further develop your knowledge of Greek mythology. Here are three of my favorites:

- The Greek Myths by Robin Waterfield has the advantage of including colorful pictures and a lot of detail told in a vivid, story-like way.

- Mythology by Edith Hamilton is considered the authoritative manual on Greek mythology. It is easy to read but at times it can be dry and it lacks some of the vivid detail of Waterfield’s book. It does, however, include a section on Norse mythology.

- Bulfinch’s Mythology by Thomas Bulfinch is another widely regarded book on the subject, though it is not nearly as easy to read as Waterfield or Hamilton. It includes many more direct quotes from the source material and is mired in detail. Go for this one if you are interested in a textbook style exploration of the topic.