It’s a new year, so many men are thinking about making changes in their lives.

Maybe you want to lose weight.

Maybe you want to get up earlier.

Maybe you want to spend less time playing video games.

Maybe you want to be less of a grump.

If you’re like many men who desire to make changes in their lives, you’ve likely attempted personal change but failed.

You’ve started diets, tried workout plans, and created budgets, only to give up on them a few weeks or months later.

What gives?

When we flounder in our attempts to improve ourselves, we typically chalk up the failure to a lack of motivation or discipline. So we read books and watch YouTube videos on increasing our motivation and discipline. But they don’t seem to help much. We might feel an initial increase in drive, but then it peters out after a few days.

Like most men, I’ve had varying degrees of success with different self-improvement goals. Why do I succeed with some and not others? As a father, I’m keen on helping my kids develop noble habits and desires. How can I better nurture their progress? As a guy in the business of “helping men become better men,” I’m always looking for insights that can help me fulfill that professional vision.

So I’ve been thinking and reading about personal change this past year. My study has taken me to psychology and behavioral science, of course. But it’s also led me to philosophy. Personal change isn’t just a matter of neurology or psychology; an element of soul is also involved. Some changes are more soulful than others.

Over the next year, I plan to share some of the things I’ve been thinking about and learning about personal change.

But to kick things off, I want to introduce you to a theory of how personal change happens that has significantly influenced my thinking about this aspect of the human experience.

Change Happens Within a Life Field

Most people approach personal change from a behaviorist approach. We treat ourselves like Pavlovian dogs. If you want to change something, you just need to connect a behavior with a reward or punishment, and then change will happen.

Want to stop procrastinating? Set up an arrangement with your friend where you have to pay him $1000 if you don’t finish a draft for a book manuscript.

Want to lose 20 pounds? Reward yourself with a trip when you meet your goal by the end of the year.

Other interventions get a bit more sophisticated and add to the reward/punishment paradigm of change. For example, you can create or break new habits by understanding the habit loop. But the habit loop model still takes a behaviorist approach. It’s all about stimulus/response. You just need to fiddle with rewards/punishments or change how rewards/punishments are connected to a behavior to effect personal change.

In the early 20th century, a German-American social psychologist took a different approach to personal change. Kurt Lewin thought humans were more than lab rats responding to punishments and rewards. He recognized that we’re complex beings with inner lives — hopes, fears, childhood hang-ups, etc. — that impact our behavior beyond the dynamics of the carrot and the stick. Our innate personality, talents/weaknesses, and unique histories will influence our behavior. Heck, even being hungry or tired can influence how we act.

Moreover, we’re beings embedded in social environments that shape our choices. Our behavior can change depending on the social situation we find ourselves in. For example, you might be able to maintain your calm with an annoying co-worker at the office, but snip at your annoying kids at home — same stimulus (annoying-ness); different behavior due to different social context. Or maybe you notice that you swear less when you’re with one group of friends than you do when you’re with another.

Besides the social environment, our physical environment can impact our behavior. How we act can be influenced by our surroundings, from how we set up our house to the season of the year. If you keep junk food in your cabinets, you’ll likely eat more junk food. You may feel less motivated during the darker winter months of the year.

Lewin called the totality of these internal and external factors that influence our behavior a “life field.”

Our life field is dynamic. It’s constantly changing depending on our circumstances. Consequently, our behavior is continuously changing.

But Lewin didn’t think we were at the mercy of our life field. We’re not just seeds tossed to and fro by the winds of circumstance. Lewin believed that by understanding our unique life fields, we can exercise our agency and manipulate the different factors within them to implement desired behaviors. Instead of being acted upon by our life force, we can act on it.

The Tension of Change: Driving and Restraining Forces

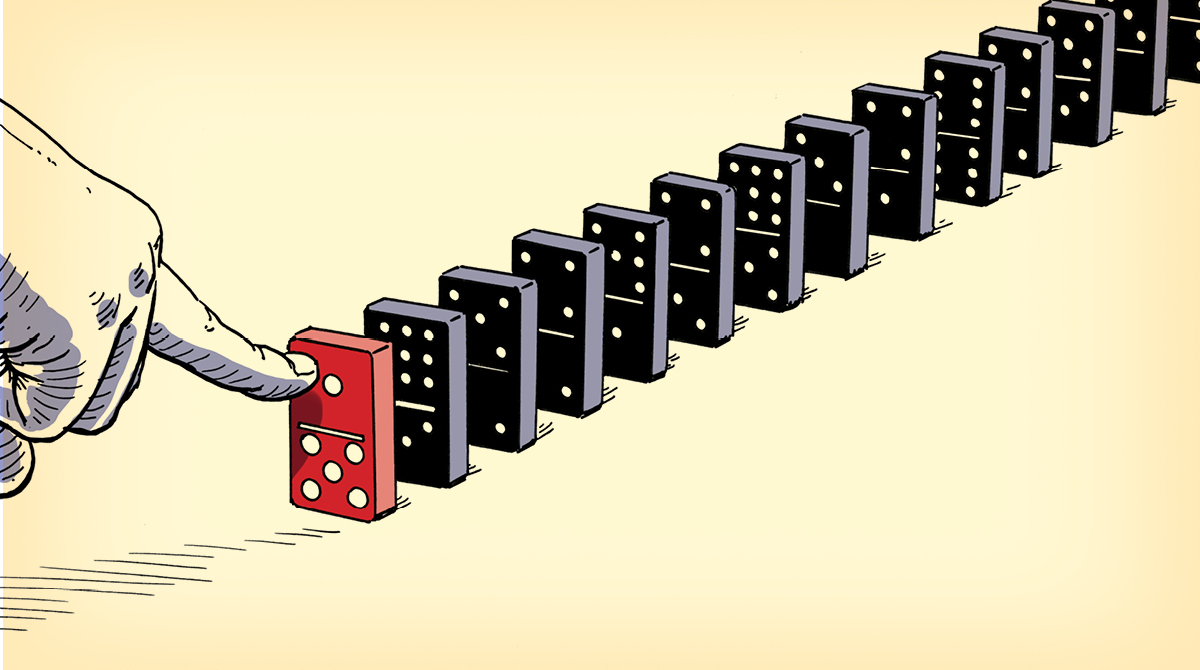

To exercise agency in your life field and change behavior, Lewin believed an individual needed to see that all behavior exists in a dynamic state between driving and restraining forces.

Driving forces are positive forces that propel us towards our goals. Our motivation and willpower are driving forces. So are skills, talents, and positive personality traits. Past successes can be driving forces in that they amplify our confidence. Money can be a driving force. The desire for status can be, too. Supportive friends and family members are powerful driving forces.

Restraining forces impede our progress toward our goals. Being distractible and neurotic are restraining forces. A lack of skills can be a restraining force. Ill health and physical disabilities can be restraining forces. Poverty and chronic stress are definite restraining forces. Living with toxic individuals can also impede your progress toward your goals.

The tension between these driving and restraining forces determines our ability to reach our goals. When our driving forces exceed our restraining forces, we can achieve our desired personal change. By identifying and addressing the different driving and restraining forces in our lives, we can look for ways to strengthen our driving forces, while weakening the influence of our restraining forces.

An Overlooked Key to Personal Change: Decreasing Restraining Forces

When it comes to making a change, we typically think of increasing our driving forces — things like motivation and discipline.

Increasing your driving forces can get you much of the way towards your goals. I’m a particularly strong believer in the idea that motivation — having an inherent desire to engage in a pursuit — is essential in achieving success in any endeavor.

But people often overlook the significance of restraining forces in successfully transforming their habits. Dr. Ross Ellenhorn, the author of How We Change (And Ten Reasons Why We Don’t), compares the interplay between driving and restraining forces to heading out on a road trip: you may have a full tank of fuel (driving forces), but if you run into a traffic jam (restraining forces), you’re not going to get anywhere.

So it’s worth flipping things around from how you may normally think about goal-setting to consider the restraining forces side of the equation.

Kurt Lewin was the intellectual grandfather of the contemporarily influential psychologist Daniel Kahneman of Thinking Fast and Slow fame. In an interview on the Freakonomics podcast, Kahneman described a key insight he got from Lewin about how to help someone else change that also applies to changing your own life:

Diminishing the restraining forces is a completely different kind of activity because instead of asking, ‘How can I get him or her to do it?’ it starts with a question of, ‘Why isn’t she doing it already?’ Very different question. ‘Why not?’ Then you go one by one systematically, and you ask, ‘What can I do to make it easier for that person to move?’

I love that question to ask yourself when you’re troubleshooting failed attempts at personal change: Why am I not doing this thing already?

Why am I not already eating right?

Why am I not already exercising regularly?

Why haven’t I already curbed my drinking?

Maybe perfectionism is holding you back from sticking to a diet. Instead of giving up completely when you don’t keep your diet with exactitude, perhaps you can give up the perfectionist mindset and settle for good enough 80% of the time.

Maybe you’ve overextended yourself in time commitments and don’t have the time to dedicate to a regular exercise routine. Do an audit and bow out of some commitments to free up some time.

Maybe you’re ready to quit drinking, but all your friends want to do is go to the bar every night. Expand your social circle and find new friends who don’t center their socializing around alcohol.

You don’t have to eliminate all the restraining forces in your life. Some restraining forces you’ll never be able to get rid of, like family members or a disability. But you can always find ways to work around them or diminish their influence on a desired outcome. Focus on what you can do, not what you can’t do.

Conclusion

Personal change happens in a life field. That life field is complex and can change based on the social and environmental context you find yourself in. You don’t have to be the nail in your life field; you can be the hammer. Spend time this year reflecting and contemplating your life field and recognize all the driving and restraining forces surrounding different behaviors. Once you do, don’t only think about fueling up on the former factor, but also getting obstacles out of the way so you can fully step on the gas and accelerate your journey toward personal change.