Editor’s Note: Last week my grandfather, who was my last living grandparent and a big inspiration in my starting the Art of Manliness, died. He was someone who I can happily say made me feel bad about myself, and of which people exclaim, “They sure don’t make ‘em like they used to.”

I was asked to give the eulogy at his funeral this weekend, and wanted to share it here on the site in honor of his legacy. I did add one story to this article that my uncle recounted.

_________________________

William (Bill) Daly Hurst passed away on September 29, 2016, just six days shy of his 101st birthday.

And what a life he lived.

My grandfather has always loomed large in my imagination. Even though we were separated by hundreds of miles and sometimes went years without seeing each other, Grandpa’s presence has always been with me. He was an icon for me and almost a kind of institutional figure — an embodiment of the values of the Greatest Generation. In fact, he’s been a big part of the inspiration behind the ideal of manhood that I write about on the Art of Manliness. He was both a good man and good at being a man.

As I look back on his life, three characteristics of my grandpa stick out to me that I hope to emulate: his dedication to service, his unyielding curiosity, and his humility.

As a third-generation U.S. Forester, Grandpa was born into a legacy of service — a commitment to protecting and managing our country’s natural resources.

It started in 1905 when William Hurst (Grandpa’s grandfather) was appointed assistant ranger on the Dixie Forest Reserve in Utah. Three months later, he became a forest supervisor. Gifford Pinchot — the first Chief of the U.S. Forest Service, appointed by Theodore Roosevelt — sent him two full pages of instructions, the most specific being, “As soon as you can get to it, please look up desirable rooms for an office. A full set of blank forms, office equipment, and furniture have been requested to be sent you.” Supervisor Hurst made a formal reply: “I will endeavor to magnify the trust reposed in me and shall discharge the duties imposed upon me in a dignified manner without fear or favor.” This was William Hurst’s rule until he resigned in 1913 as supervisor of the Beaver and Fillmore National Forests, and it was a rule my grandfather followed during his tenure in the Forest Service.

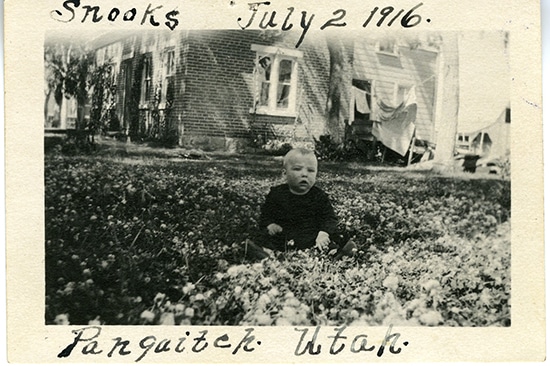

My grandpa at 9 months old. His family nickname was Snooks.

William M. Hurst (my grandpa’s father) started as Assistant Ranger in the service in 1910 in Panguitch, Utah. He was a District Forest Ranger when my grandfather, William D. Hurst, was born on October 5, 1915, in Parowan, Utah.

Think about that for a minute. My grandpa was born a year into the First World War. In his memoir he recounts his memory as a three-year-old of people banging pots and pans and whooping in the streets on Armistice Day. My grandpa was what blogger Jason Kottke calls a “human wormhole.” His long life and the amount of history he saw firsthand provide an embodied reminder of just how connected we are to the past. When I gave my grandfather a hug, I was hugging a man that was hugged by his grandparents who were born during the Civil War. That idea really puts time in perspective for me.

Grandpa was raised in Panguitch, Utah, and graduated as student body president and co-valedictorian of his class at Garfield County High School in 1934. He attended Utah State Agricultural College and graduated with a B.S. in Forestry and Range Management in 1938. During the summer months of his college years, Grandpa worked as a sheepherder, where he accumulated some pretty cool stories. In his memoirs he describes in explicit detail how to castrate sheep; the methodology was just as Mike Rowe famously explained it: a sharp knife and your teeth.

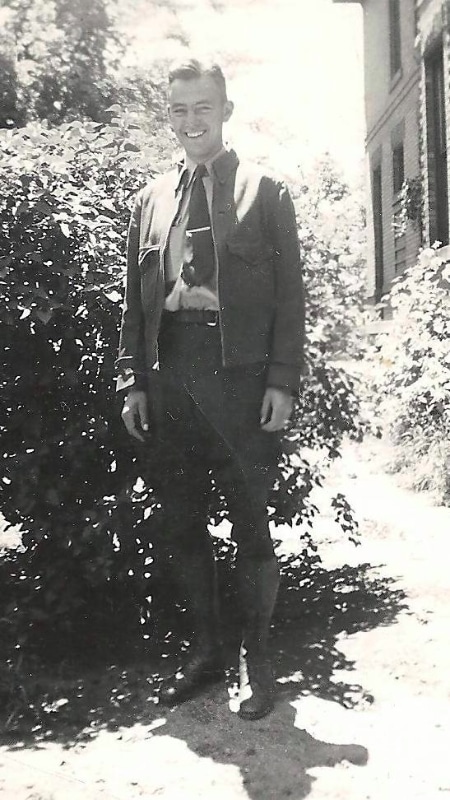

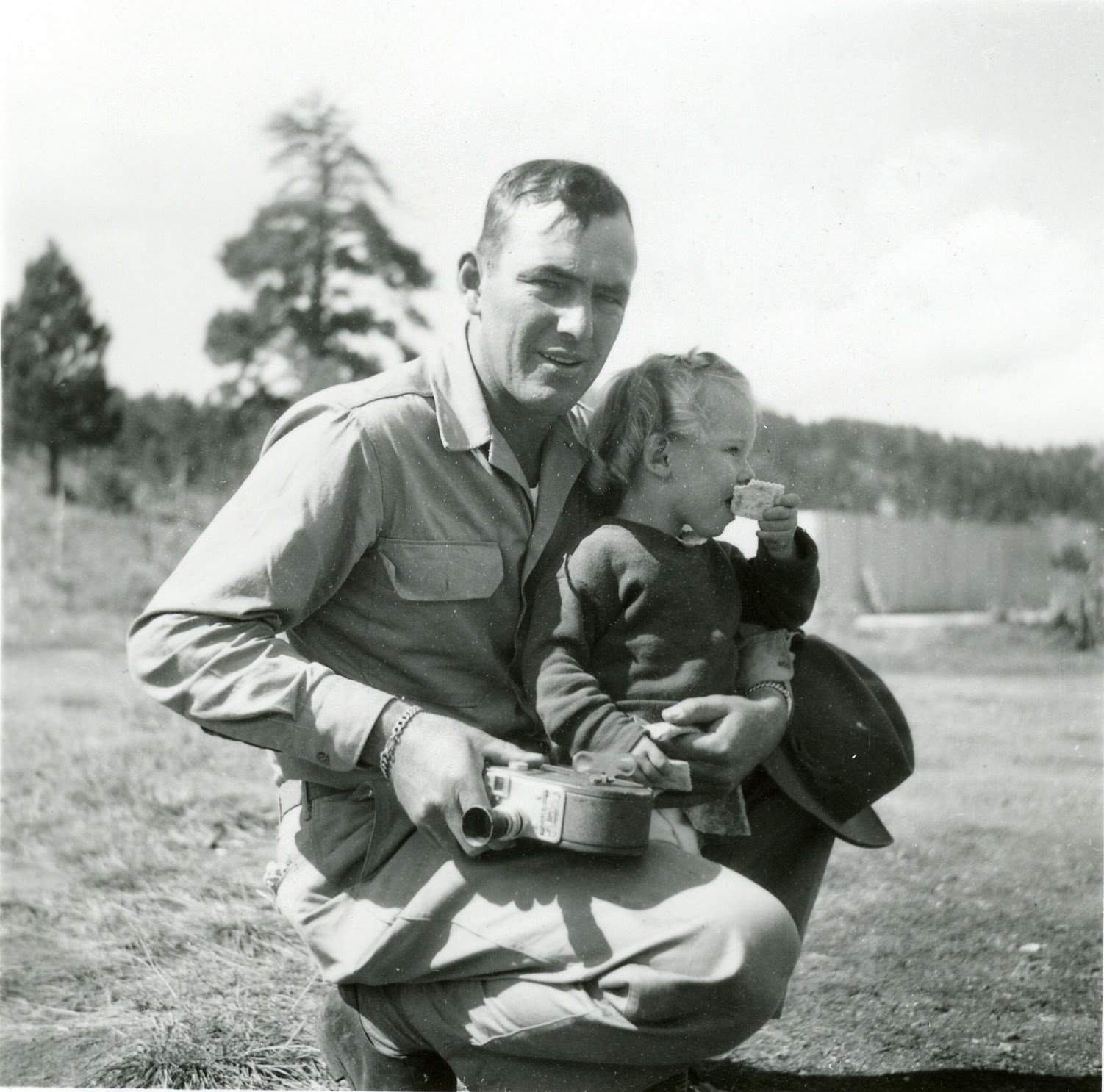

Grandpa’s first day working for the U.S. Forest Service.

During the summer of 1937, he worked for the United States Forest Service as an Administrative Guard in the Stansbury Mountains near Grantsville, Utah. After graduation, he took a permanent assignment with the Forest Service in the same location, thus becoming a third-generation forester in Utah, after his father and grandfather.

Bill and Dolly Hurst.

In Grantsville, he met his sweetheart, Emma (Dolly) Johanson. Grandma worked as phone operator and Grandpa came into town one day to make a phone call. He was immediately smitten and I’m sure started finding reasons to make more phone calls. They were engaged in 1940 and married March 19, 1941.

In 1942, Grandpa became the District Ranger of the Manila Ranger District on the Ashley National Forest.

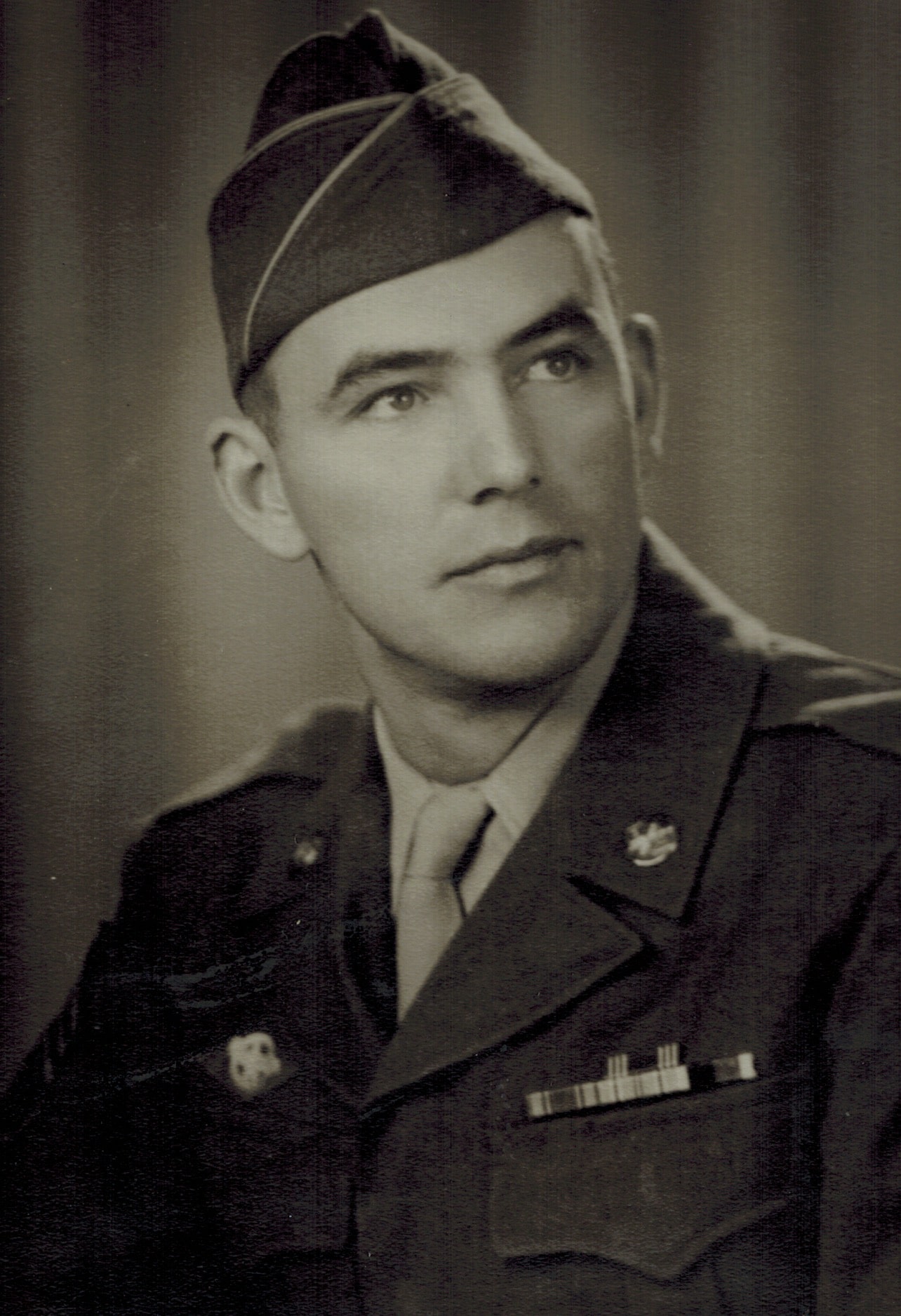

Like millions of men from his generation, Grandpa answered the call to serve and fight for his country during World War II. He served in the Army, training for the invasion of Japan, and then spent one year in that country as part of the occupation forces in 1946.

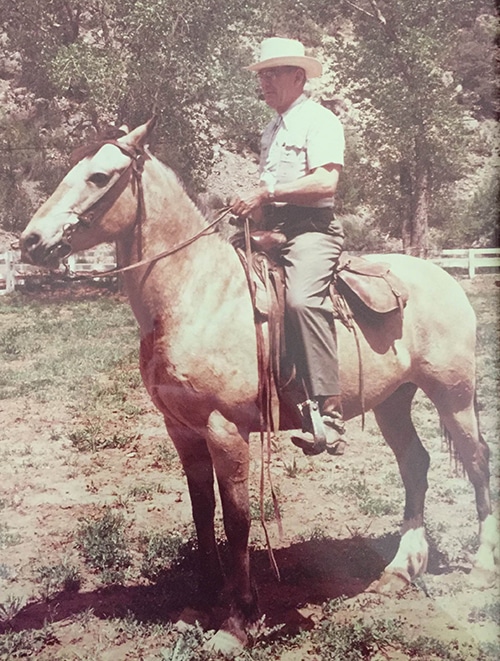

Grandpa riding a horse while serving in the Army in Japan during WWII. 1946.

Grandpa was 31 years old when he began his military service, making him much older than many of the soldiers in his platoon. That earned him the nickname “Pops,” but he took pride in the fact that he could out-hustle and outwork men ten years his junior. After the war, Grandpa continued his service in the U.S. Army Reserves, obtaining the rank of first lieutenant.

Staff at the Ashley National Forest where Bill Hurst served as supervisor from 1950 to 1955. Grandpa’s in the middle holding his hat.

After leaving the military, he became the Staff Officer of the Cache National Forest in Utah. He served as Forest Supervisor on the Ashley National Forest from 1950 to 1955, before going to the Washington office as one of the Assistant Chiefs in Range Management. Grandpa then served as Chief of Range & Wildlife Management of the Intermountain Region from 1957 to 1962. He was the Deputy Regional Forester for the Intermountain Region as well. In 1966, Grandpa was appointed Regional Forester for the Southwestern Region, where he remained until he retired in 1976.

Bill Hurst served as Regional Forester of the Southwest Region from 1966 to 1976. He’s in the middle.

During his appointment as Regional Forester of the Southwestern Region, Grandpa brought not only a keen mind and almost 30 years’ experience, but also a pride in the history and traditions of the Forest Service and a genuine concern for the well-being of the forests and the people who used them. He imparted a level of professionalism to his region that still remains today.

As a Regional Forester, Grandpa didn’t have an ideological axe to grind nor did he have political ambitions within the Forest Service. He just strived to follow his own grandfather’s rule to “discharge the duties imposed upon me in a dignified manner without fear or favor.” Grandpa was a pragmatist. He just wanted things to work and work well for everyone. And that often meant trying to find a middle ground among multiple parties who all had conflicting interests — ranchers, farmers, timber companies, indigenous people, and environmentalists just to name a few. And he was able to walk this line for the most part thanks to his curiosity and humility. He talked to people, asked questions without prejudice or preconceived notions, and researched on his own. But more importantly, Grandpa took action and found solutions and compromises that could prevent gridlock and keep things moving forward. (Note: For those of you interested, Utah State University has digitized diaries, reports, etc. from my grandpa’s career as a forester.)

Grandpa retired from the Forest Service in 1976 and spent his retirement at his home at Bosque Farms — a small ranch in New Mexico. Here he provided idyllic summers and Thanksgivings for his grandchildren, full of swimming and horseback riding. For me, Bosque Farms is where my most cherished memories of Grandpa, and of my childhood, exist.

Bosque Farms was a Garden of Eden. But time eventually drove us all out of this Western paradise. Grandpa got too old to manage the place by himself, and we all got older and busy with our adult lives. But Bosque Farms is a place I still long for. Every now and then, memories of spending time with Grandpa on the ranch hit me like a tidal wave.

I miss the smell of coffee and hotcakes in the morning and the smell of pinyon wood burning in the living room fireplace. I miss the smell of the barn on a clear, crisp Thanksgiving morning.

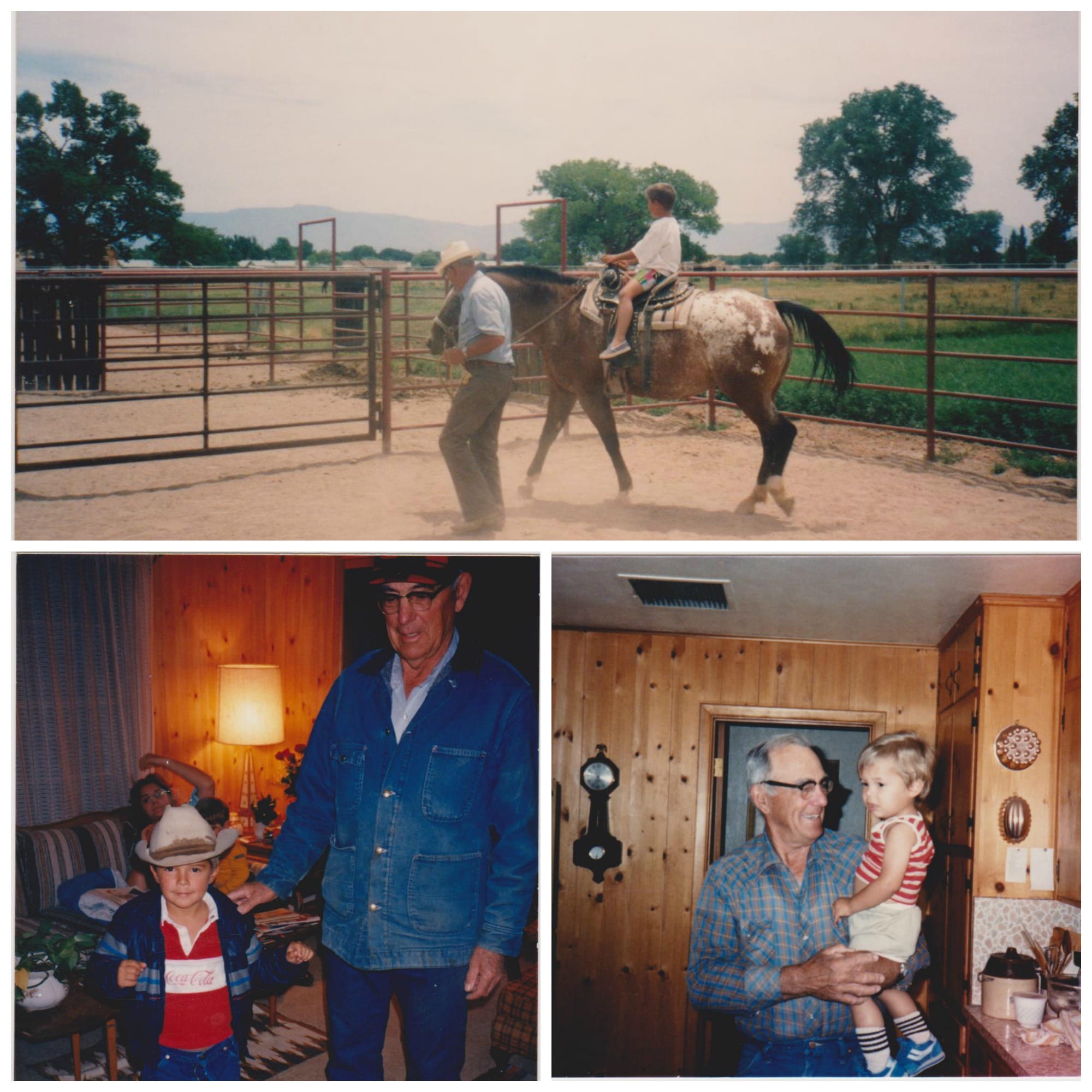

But most of all I miss Grandpa leading me around the corral on a horse, patiently and lovingly telling me how to guide my noble steed.

Pictures of me and Grandpa at various times at Bosque Farms, New Mexico. Still have that hat Grandpa gave me.

It’s a painful yearning to return home. The Greeks called this nostalgia. While my heart aches for that time, it’s a good ache. I’m glad I have those memories and I’m indebted to Grandpa for giving them to me.

Even in retirement, Grandpa continued his dedication to service. If there was a club or organization dedicated to service, he belonged to it. He was a charter member and past president of the Society for Range Management where he continued his work in conserving and managing our country’s natural resources. He was also a member of the Lion’s Club, Rotary, the Society of American Foresters, and the Wilderness Trail Riders of Prineville, Oregon.

Grandpa was active in Scouting and was awarded the Silver Beaver for distinguished service. He was also the grateful recipient of Rotary’s Paul Harris Fellow award, the Jim Bridger Award for conservation achievement, and the Lifetime Achievement Award from Utah State University, as well as the 2004 Frederic G. Renner Award from the Society of Range Management — the most prestigious award given by the society.

Grandpa and my Aunt Kathy.

Grandpa’s service wasn’t only to the public and his community but to his large and ever-growing family as well. Grandpa was always looking out for us and made frequent trips to visit all of his grandkids during retirement. He even drove by himself from Albuquerque to Tulsa when he was 90 years old to come to my wedding. Kate’s grandma thought he was crazy, but Grandpa didn’t think much of it.

Grandpa and Grandma Hurst with their five children.

He is preceded in death by his wife, Dolly, and his sister and brother-in-law, Margaret and Ralph Tingey. He leaves behind his sister and brother-in-law Katherine and Vernon Barney of Panguitch, Utah, five children and their spouses, nineteen grandchildren, thirty-four great-grandchildren, and numerous nieces and nephews.

Grandpa’s entire life was dedicated to service — to his country, to his community, and to his family. If he could help in some way, he was there.

Whether in work or play, Grandpa also stayed curious. It’s one of the most refreshing and vital things about him. He was always reading books to learn more and taking notes in the pocket notebook he kept in the breast pocket of his shirts.

My uncle recounts a story of this note-taking practice: When my grandpa was 90, my uncle found him reading a book, but stopping every now and then to write in his pocket notebook. When my uncle asked Grandpa what he was doing, he said, “I’m writing down the words I don’t know the definition of so I can look them up later.” When my uncle asked him why he was doing that, Grandpa responded matter-of-factly: “To improve my vocabulary, of course.” Ninety years old, and my grandfather was still trying to enrich his treasury of knowledge.

Another example of Grandpa’s curiosity in action can be seen in his retirement, when one of his old phonograph players broke. He learned how to fix it (this was before the internet, mind you), which led to a small side hustle in retirement repairing phonograph players for others. He did the same with antique buggies. He became a self-taught expert on repairing and restoring them, and people started paying him to fix up theirs.

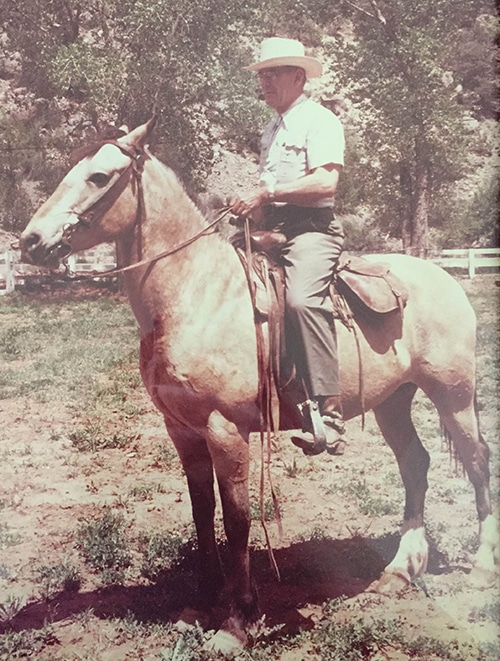

Grandpa was always happiest out in the mountains somewhere on a horse.

Grandpa traveled extensively throughout his life within the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, in addition to China, Panama, Russia, and the U.K., though he was happiest riding his horse or mule on adventures through the mountains of the West from New Mexico to Oregon.

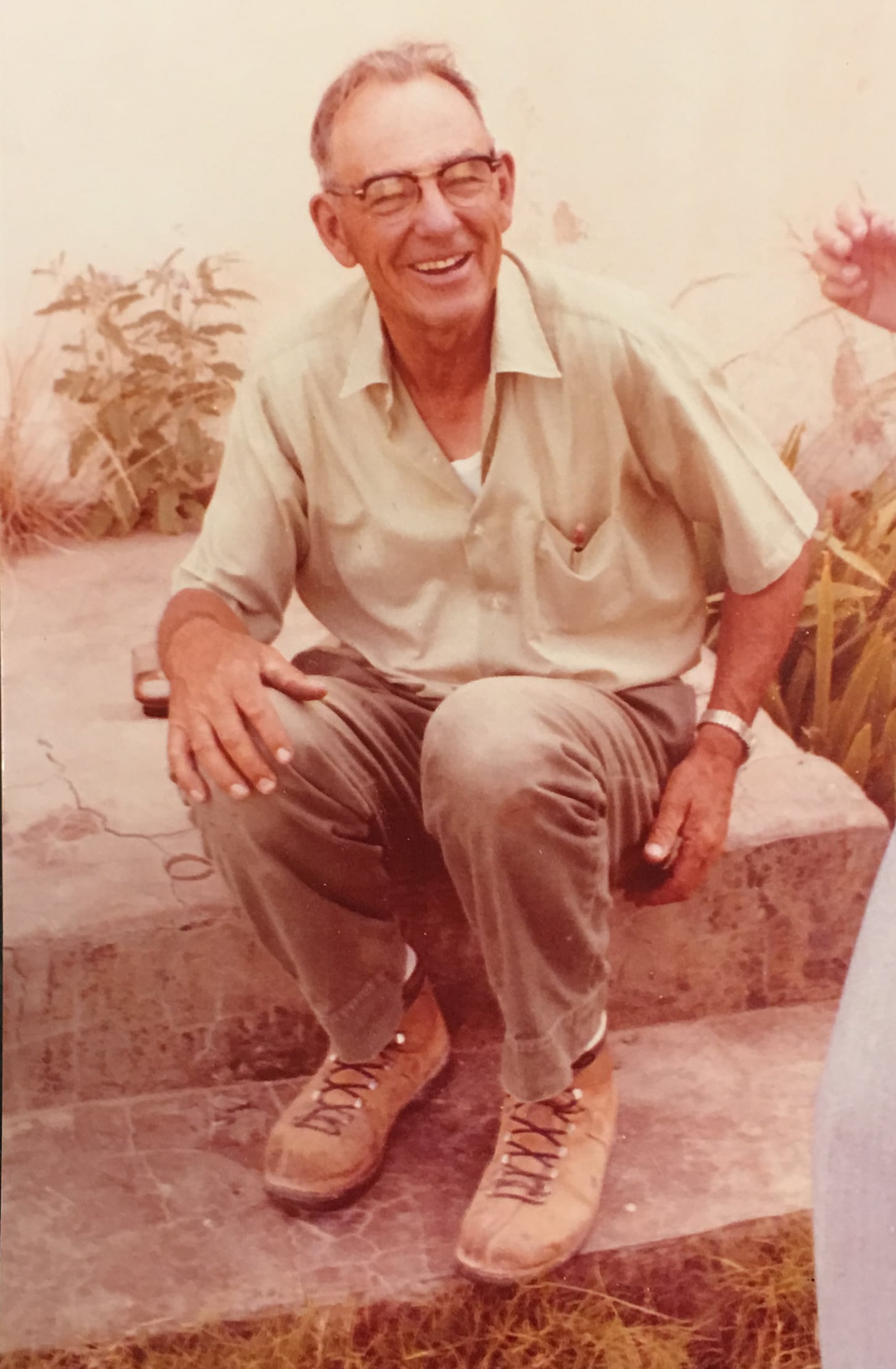

But what I loved most about Grandpa’s curiosity was his genuine interest in others. He wasn’t jaded or cynical about people at all. He sincerely thought every person — no matter their walk of life — had something interesting to say. Grandpa could go anywhere and have a friend because he could make one instantly. As a kid, this interest in others could get kind of annoying. I knew going on quick errands with Grandpa would often result in me standing around waiting for thirty minutes while he talked to complete strangers, sharing stories with them, peppering them with questions, and intently listening while interspersing the conversations with his characteristic chuckle and “Well, I’ll be damned!” or “Well, that’s a hell of a thing!” And he meant it! He was always genuinely surprised by and interested in the things people would share. Like Will Rogers, Grandpa “Never met a man he didn’t like.”

Finally, Grandpa didn’t take himself too seriously. He took his work very seriously, but never himself. There was never an air of self-importance about him. Because of his humility, I sometimes forget about his accomplishments and the amount of influence he has had in public affairs, particularly when it comes to conservation. Grandpa was too busy being useful to worry about being important.

What I’ve spoken of are just the highlights of Grandpa’s earthly sojourn.

Like I said at the beginning…what a life.

He’s been an inspiration to me, and can serve as a pattern for all of us seeking to live the good life.

We will miss Grandpa, but I’m thankful for the example of service, curiosity, and humility that he gave us. I’m looking forward to seeing him again one day, and until then I hope we all will do our best to live up to his legacy.

Bill Hurst’s grandsons were his pallbearers at his funeral. We all wore one of Grandpa’s iconic bolo ties in honor of him. Those of us who had cowboy boots also sported those. My cousin, Tom Hughes, shared this thought about the experience: “My grandfather, Bill Hurst, died last week, 6 days shy of his 101st birthday. As I and my cousins, the pallbearers, stood in a semi-circle, looking at his flag-draped coffin in the back of the hearse, we said almost nothing. We just stood there for several minutes until the funeral director came out, found us standing there, and told us we could get in our cars. I don’t believe there has ever been group of boys–now men–who more loved, admired and revered their grandfather than those of us standing there, wearing his bolo ties. And I know his granddaughters feel the same way. Pity there weren’t more bolo ties for them.”

____________

When my grandpa was 9 years old he encountered a tassel-eared squirrel on the Kaibab Plateau in Southern Utah, an area that’s 20 by 40 miles wide. It was the Kaibab Squirrel — a species not found anywhere else in the world. Since that time, Grandpa took a keen interest in this little critter and strove to protect it in his position as Regional Forester. Nearing his 100th birthday, Grandpa, along with some friends and family, formed the “Friends of the Kaibab Squirrel,” a group dedicated to educating federal and state agencies and citizens about this unique animal, so that pragmatic steps can be taken to prevent population decline. Should you like to honor my grandfather at his passing, you can support Friends of the Kaibab Squirrel by purchasing a lapel pin. Proceeds go to FKS.