We don’t typically think of hospitality as a manly thing. And indeed, it is typically the women in our lives who more often take charge of throwing parties, cooking meals, and preparing the guest room for visitors.

But for thousands of years, offering hospitality was considered an essential part of being a man and living with honor.

While many ancient cultures had a code of honor which required the practice of hospitality, this code was especially typified by the form it took amongst the Greeks.

The Ancient Greek Idea of Hospitality

In the 1970s, anthropologist Michael Herzfeld studied the culture of masculinity in a small mountainous village on the island of Crete that he dubbed “Glendi” (the name was a pseudonym, to protect the confidentiality of its residents). The Glendiots were a pastoral people who, because of the remoteness and hardscrabble nature of their village, had retained much of the traditional code of manhood that had marked cultures around the world since ancient times. One of the things Herzfeld discovered about that culture was “that the height of eghoismos, self-regard, is a lavish display of hospitality.”

The Glendiots’ emphasis on hospitality traces all the way back to ancient Greece, when it was called xenia. Xenia was an honor-based code of etiquette that concerned the relationship between hosts and guests, especially between hosts and guests who were strangers to each other.

So what did good xenia look like in ancient Greece?

Well, a host was expected to welcome into his home anyone who came knocking. Before a host could even ask a guest his name or where he was from, he was to offer the stranger food, drink, and a bath. Only after the guest finished his meal could the host inquire about the visitor’s identity. After the guest ate, the host was expected to offer him a place to sleep. When he was ready to leave, the host was obligated to give his guest gifts and provide him safe escort to his next destination.

Guests in turn were expected to be courteous and respectful towards their hosts. During their stay, visitors were not to make demands or be a burden. Guests were expected to ply the host and his household with stories from the outside world. The most important expectation was that the guest would offer his host the same hospitable treatment if he ever found himself journeying in the guest’s homeland.

Once you understand the ancient Greek concept of xenia, you’ll start to see it everywhere in ancient Greek texts. The Odyssey is basically the Greek bible on xenia. Pretty much every story in it has something to teach about either neglecting or upholding the tenets of xenia.

Circe turning Odysseus’ men into pigs? Bad xenia.

The cyclops eating Odysseus’ men? Bad xenia.

The Phaeacians giving Odysseus a banquet and gifts? Good xenia.

The suitors mooching off Odysseus while he was gone? Bad xenia.

Why Was Hospitality an Important Part of Male Honor?

While xenia particularly emphasized the importance of treating strangers well, the Greek concept of hospitality encompassed one’s treatment of friends, family, and neighbors as well. And the reason the ancient Greeks (and other ancient peoples) elevated hospitality to a prominent place in the manly code of honor range from the social to the practical to the religious:

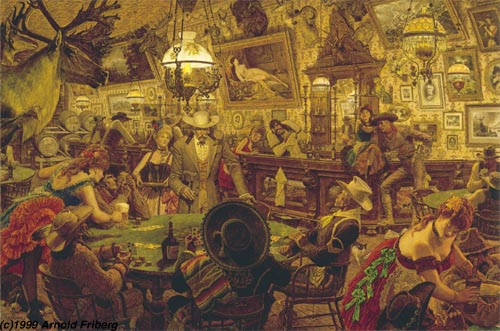

Earning/showing status. Manhood has always been a hierarchical dynamic. Men look for ways to raise their status, and for the ancients, one of those ways was through what historian Nigel M. Kennell calls “displays of competitive generosity.”

In setting out ample spreads for strangers and throwing lavish parties and weddings for family and friends, men demonstrated that they had resources, that, among the 3 P’s that traditionally marked the code of manhood — protect, procreate, and provide — they possessed plenty of skill and prowess in that latter category.

“Glendiot hosts not only vie with each other to treat strangers,” Herzfeld observes in The Poetics of Manhood, “they are also engaged in continual competition with one another”:

In the village houses of the Glendiots, meat is often served out of a large cauldron (tsikali) in which it has been cooked by women. Its preparation, however, is again often begun by men, who do the initial cutting of meat with their personal knives.

. . .

A host who serves only a small amount of meat feels embarrassed since a meal without meat is not considered a meal at all. At wedding and baptismal feasts, huge amounts of boiled and roast lamb and mutton, roast pork, and sometimes also chicken and organ meat are consumed.

In serving a smorgasbord of meat, Glendiot men showed they knew how to hunt, how to steal sheep (which was a big deal amongst this shepherding people), and how to care for and obtain other animals. And in slicing the meat up, they showed they were adept in wielding a knife.

A similar dynamic of competitive generosity can be seen in the ancient Greek city-state of Sparta. Each Spartan man was required to eat all his meals with his syssitia — his dining club or mess. Once the members of each syssitia had eaten their standard rations, members treated their messmates to foods that had to be, as the rules of the syssitia dictated, either raised/grown on their land or hunted themselves, and which could have included wild game, fruits, vegetables, herbs, nuts, eggs, milk, cheese, butter, and bread. “Before serving,” Kennell explains, “the cooks announced the name of the day’s donor to his grateful companions so that they might appreciate his hunting prowess and diligence for them.”

Among the Glendiots, even a situation where a man didn’t have a lot to offer his guests could still be an opportunity to display a different kind of status-elevating skillfulness:

even when large amounts of meat cannot be found quickly enough, the host may be able to emphasize his generosity, and above all his manhood, in another way. He may apologize for the poverty of his table, pointing out that the guests would have to be content with ‘whatever can be found’ (to vriskoumeno). This phrase invokes a crucial principle. Ability to improvise, to make the most of whatever chance offers, is the mark of a true man. It is unthinkable for a Glendiot to refuse to entertain extra guests; on the contrary, he is expected to make the most of what he has.

Building alliances. In being a generous host, a man elevates his status and, as Herzfeld observes, places the guest in a position of symbolic dependence. The host provides; the guest receives. And yet ironically, by treating someone, the host also initiates an egalitarian relationship:

the treat (kerasna or trattarisma) establishes a fleeting advantage for the giver, an advantage which the latter is expected to redress in the ordinary course of village interaction. Yet the same act of establishing a temporary obligation (ipokhreosi) between host and guest also equalizes the relationship between the newcomer and the rest of the company. Once he has sat down and accepted his treat, he is on an equal footing with the others.

When a host offers hospitality, he creates an obligation in the guest to return the favor. This creates a dynamic of back-and-forth treating, of reciprocity, and thus of equality. It ensures future interactions, the development of increasing familiarity, and ultimately, the building of trust.

Offering hospitality was thus a central way for ancient men to build alliances and enhance their social network. As Joe Keohane, author of The Power of Strangers explained on the AoM podcast, having this kind of network was crucial in a period and landscape that was less organized and secure:

the reason why [hospitality] is so sacred, that it was so important to the Greeks, is because it was a chaotic world; you didn’t have central institutions; you didn’t have national armies or police or governments or things like that, necessarily. There was a great deal of conflict. And in order to travel in that world, and in order to flourish in that world and develop trading relationships and all the stuff you have to do, you needed to be able to make friends, you needed to make alliances. So when a stranger came to town, it was a big deal, it was an opportunity, right? It was an opportunity to make a friend, to learn something about the world, to get news, to maybe gain access to an innovation, and it was reciprocal . . . you would host this person, you’d give them lots of food, you’d be really good to them, maybe they stay a couple of days, whatever, but now you have an ally later.

So if you need a favor, if you’re traveling through this unstable and dangerous world, there’s a person that you can go crash with. And the idea is the more people who did that, the bigger their social networks became and the easier it became for them to move and for them to live in the world.

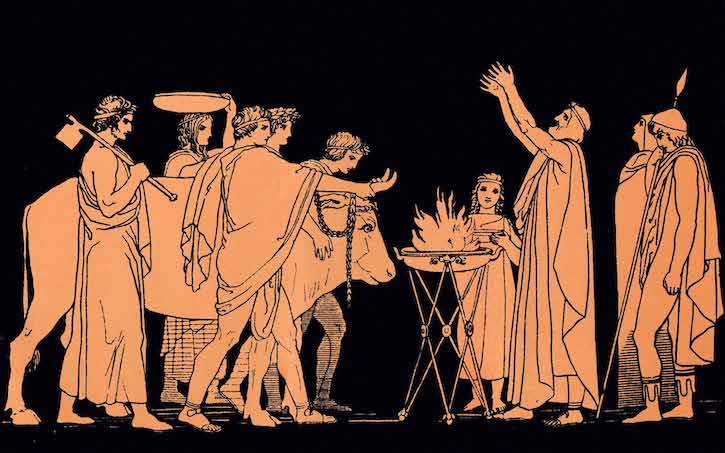

Reverencing the gods. Hospitality was so important to the ancient Greeks that they made Zeus its patron god. In myths and stories, Zeus took up the guise of a wandering beggar to see if mortals were practicing xenia. It was kind of like Undercover Boss. If a mortal treated a disguised Zeus poorly, that mortal would receive the divine wrath of a vengeful deity. So a lot of ancient Greeks just assumed all strangers were potentially the king of the gods himself and treated them with generous hospitality.

In one of Ovid’s fables, Zeus and Hermes, in the form of ordinary peasants, knock on the doors of home after home in a Greek village, asking for a place to stay. But all the townspeople, even the rich ones with plenty of resources to spare, reject these strangers. All except for Baucis and Philemon, an old couple who, despite their poverty, invite the disguised gods in, and offer them their best food and drink. As a reward for their sacred gesture of generosity, Zeus and Hermes spare Baucis and Philemon from the flood they unleash on the rest of the village to punish the pair’s “wicked” neighbors, and turn the couple’s homely cottage into a beautiful temple, for which they will serve as guardians.

While the ancient code of hospitality wasn’t practiced for purely altruistic reasons, and was instead propagated by a mix of self-interest and piety, neither are our own actions — no matter how lofty and virtuous the cause — ever entirely unselfish. Yet as with all plays for status and such, acts of hospitality end up benefiting both the host and the guest, and even society as a whole. For while we may no longer be navigating a landscape that’s as chaotic and unstable as it was two thousand years ago, being human remains a stubbornly difficult enterprise. Everyone could use more way stations along their journey — people who are willing to literally or metaphorically take us in. Everyone could use a good rest, whether from a day of effortful travel or from a seemingly hopeless barrage of news. Everyone could use some nourishing repast, whether in the form of real food or a word of encouragement. Everyone could use a gift, whether it’s a new winter coat or some sincere attention.

Being a host means not only sheltering a guest or throwing a party, but being the person who takes the initiative in reaching out to others, who starts the conversation, and makes others feel comfortable within it. It’s a role you can adopt in any situation, wherever you are — even when you are, in fact, technically the guest. Whether you’re on the subway or a plane, or at work, church, or someone’s else’s party, you can serve as an oasis of warmth; you can help make other people feel “at-home.” In reviving the ancient code of hospitality, you can aid strangers, friends, and family in their sojourn, create a domino effect of good deeds by encouraging others to pay the kindness forward, and, maybe, even end up entertaining angels unawares.