Does it seem like people are more tired and less motivated and ambitious these days?

They do less hosting and attending of events.

It’s harder to get them to volunteer to run the school carnival or participate in a church service project.

Hustle culture is out; self-care is in.

People seem just to want to get through life, rather than transcend it; they’re more apt to aim low rather than for the stars.

If this perception of a widespread energy ebb is accurate, what’s behind it?

We have a hypothesis.

The Tipping Point

When smartphones first started taking off, which, strange to recall given their current ubiquity, was only a decade and a half ago, the subsequent years were filled with a fair amount of concern and contemplation as to how these devices were affecting our brains, behaviors, relationships, and culture.

The disruptions to our minds that technology was causing were novel, and thus easily recognizable and highly salient. And we turned to books and blogs to help us make sense of these changes and how to navigate them.

Websites offered thousands of articles on how to manage the increasingly distracting pull of digital devices: Turn off notifications! Put your phone in a desk drawer while you work! Download apps that block the use of other apps!

Throughout the 2010s, books like The Shallows, which offered explanations as to what technology was doing to our brains and how to control its allure, were bestsellers. Cal Newport’s Digital Minimalism was really the last significant gasp in this genre, and the year of its publication — 2019 — was really the last period where people felt determined to put a leash on their relationship with their phones.

Then, a shift occurred.

It started with COVID. People who had tried to avoid checking their phones too much, who had committed to not looking at them first thing in the morning, began reaching for their phones as soon as they got up and started scanning the headlines far more frequently to see what was going on. How was the virus spreading? How dangerous was it? What were the local infection numbers? The political and social unrest that also took place in 2020 only increased the number of times people checked the news and scrolled through their phones. And as more folks started working from home, their phones had to be checked not only for personal updates but professional ones, too.

The last bit of distance people had tried to maintain between themselves and their devices collapsed. They surrendered to their attachment and fairly fused with their phones. Whereas they had occasionally been left in another room or not always taken in the car, phones were now kept permanently close at hand.

Today, almost no one writes or thinks about how to be less distracted by your phone. It’s not that technology has stopped affecting our minds. It’s not that we no longer experience some disquiet over the effects of our phones. But because these effects are no longer novel, we experience them far less frequently and acutely. We’ve accepted their presence in our lives. We’ve become accustomed to the current state of our thoughts and behaviors. It feels like our normal. Whereas a decade ago, we could sense how our lives were being changed, now we can no longer remember what our old lives were like.

The Modern Bandwidth Shortage

While we may no longer be registering the impact that technology is having on our thoughts and behaviors, that impact continues as strongly as ever.

Much of it centers on the fragmentation of our attention.

As Dr. Gloria Mark shared on the podcast, when we switch from paying attention to one thing to paying attention to another, it takes us an average of 25 minutes to return to that original task. In that time, we do or think about two and a quarter other things, on average. “So we get interrupted, either by ourselves or by something external to us; we’re working on a second thing; we get interrupted again, so then we begin working on a third thing; we get interrupted again, [and] we start working on another project, and we only spend roughly about a quarter of the time compared to the others on that. And then we go back to the original task.”

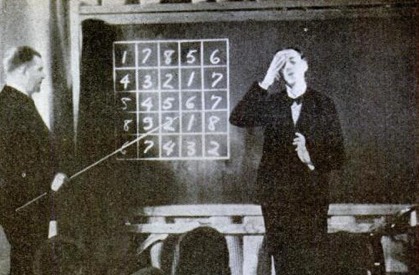

Gloria compares this task-switching to writing on and erasing a whiteboard. As you think about/work on something, you draw a schematic of it on the metaphorical whiteboard of your mind. When you get distracted by something else, you erase that sketched-out mental model and have to create a whole new one for the new task.

Work for 5 minutes. Check your phone. Work for 5 minutes. Check your phone. Work for 5 minutes. Check your phone. Work for 5 minutes. Check your phone.

Draw. Erase. Draw. Erase. Draw. Erase. Draw. Erase.

The result of this constant mental construction and deconstruction is that you end up feeling fatigued and frazzled. And your mind never feels entirely clear: to return to the whiteboard analogy, even when you wipe the marker away, faint traces of it often still stick around. In the same way, vestiges of the previous thing you were thinking about leak into the current thing you’re thinking about; part of your brain is still thinking about the dumb reel you just saw on Instagram as you’re talking to your kid about her day.

If you’ve felt like your mental bandwidth is always operating in a state of reduced efficacy, it’s not just in your head. Well, it is in your head, but there’s a reason for it. In addition to using your bandwidth for all the actual tasks you need to get done in a day, it’s also being drained by the energy vampire that is your phone.

Life in a Low-Bandwidth World

Nearly all modern citizens are walking around in a state of bandwidth depletion, and the downstream effects of this cannot be underestimated.

Working hours have actually declined over the past century, and are lower than in the 1950s, when Grandpa still managed to be a member of the Rotary Club, serve as a Boy Scout leader, and play bridge a few times a week with his friends. But folks today feel busier. They feel tired. They feel overwhelmed. They feel like “I just can’t take that on right now.”

On an individual level, this means that people are less inclined to set ambitious goals, initiate social interactions, pursue hobbies, and volunteer for service opportunities.

On an institutional level, organizations will find that members do the bare minimum and participate more sporadically. People may, for example, say that they miss the days when their church did more potlucks, sponsored a basketball league, and had a more comprehensive youth program . . . but they don’t want to take on the role of re-establishing these things, and even when an event is held, they don’t attend. Modern citizens continue to like the idea of community, but don’t feel capable of contributing to the effort that its creation and maintenance requires.

When individuals interact with institutions, which are run by bandwidth-challenged staff, they are often forced to deal with frustrating incompetence. In response to these frustrations, individuals, both because of the loss of moral education and because of the depletion of their bandwidth (which helps regulate impulses), behave poorly and react with disproportionate outrage and rudeness.

So, what can be done?

Well, you can take a page from the 2010s and re-commit to doing those now-cliche–but-still-potentially-effective techniques for putting some distance between you and your phone. Delete TikTok; put a time-restrictor on those sites you get lost in; use a real alarm clock so looking at your phone isn’t the first thing you do after getting out of bed. Re-listen to this episode we did with Cal Newport so you can re-remember how much you love the idea of becoming a digital minimalist.

Now, realistically, no matter how psyched up you get to rein in the grip your phone’s got on you, you’re going to fall short of fully curbing its distractions; it’s a worthwhile battle to fight, but an endlessly uphill one. The ubiquity of technology in our day-to-day lives ensures that the challenge will always be with us, and that no citizen of modernity will ever have the same degree of bandwidth as someone living in 1995. And, no matter how much distance you put between you and your phone, you’re still going to be inhabiting a world where everyone else is still very attached to theirs, and operating with the compromised bandwidth to match.

So, it is perhaps of even more importance for both individuals and institutions to adjust their expectations and mindset.

Institutions should expect that it will be hard to get involved, larger-scale programs off the ground because members won’t feel they have the bandwidth to participate in and run them.

Individuals should expect that they can no longer rely on institutions, which have pared themselves back, to serve the life-scaffolding functions they used to. You can’t rely on workplaces to buttress your social life; you can’t rely on schools to give your kids a grade-A education; you can’t rely on churches to provide all of your spiritual sustenance. The modern citizen is largely on his own.

It’s ironic that there’s never been so much put on the individual at the precise moment that he’s operating with low bandwidth. But low bandwidth doesn’t mean no bandwidth. The modern individual — and organization — that will continue to flourish has to choose a select number of core competencies he wants to concentrate on.

While it may be harder than ever to take on multiple responsibilities, you can still do a few things really well (and will need to, as institutions won’t be there to pick up the slack!). Say no to anything superfluous. Know what you’re about. Cultivate an excellent family; supplement the moral, physical, and intellectual education your kids are receiving in the wider world. Focus on important work; choose the 20% of pursuits that have an 80% effect in moving your professional life forward. Maintain a few choice friendships; invest in those people for whom your feelings are ardent rather than ambivalent. Dedicate yourself to one community or religious role; institutions still have a part to play, so help them perform the essential functions they do uniquely well.

Surviving and thriving in a low-bandwidth world requires becoming a minimalist in the best and most expansive sense; true simplicity is possessing clarity of purpose.