We started the last post in this series with a surprising fact–that only about 33% of our ancestors were male. We’ll begin this post the same way:

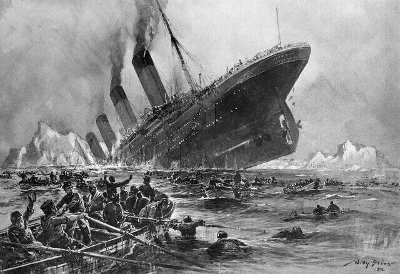

When the Titanic sunk, the survival rate for the rich, first class men (34%), was lower than that for the poor, third-class women (46%).

Most people know that the Titanic had less lifeboats than were needed for the number of passengers, and that the richest passengers were given first dibs on those limited seats. And yet, the numbers tell an interesting tale. What happened? Many of the wealthy men decided to let the women, regardless of class, get on the lifeboats first, choosing instead to go down with the ship themselves.

Women and children first. You’ve probably heard this expression all your life, so much so that you may not have paused to ask yourself the reasoning behind it…why have the lives of women historically been worth more than the lives of men?

The Expendability of Men

The answer goes back to what we discussed last time in the Switch of Challenge and can be traced to the biological differences between men and women. A woman can only get pregnant by one man (at a time) while one man can impregnate multiple women. A group with five men and one woman is not going to be able to have as many babies as a group of five woman and one man. This is why a woman’s eggs, and her womb, have always been much more valuable than a man’s seed. And why, coupled with our greater physical strength and propensity for risk, men have always been slotted for society’s dirtiest and most dangerous jobs. Like hunting and war. This is true from primitive times down until the present day. Societies had to protect their women if they wanted to survive and thrive.

In World War I, there were 9.7 million, almost exclusively male, military deaths. The number boggles the mind: 10 million men went off to war and never came home. Enormously tragic, but on a certain level we accept it; it is inconceivable to imagine 10 million women being sent to the slaughter instead.

6,026 American service members have died in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Only 2% of the fallen were women.

Men made up 93% of the 6,000 on-the-job deaths last year.

We cheer and are touched when we hear stories of men laying down their lives for women who covered his wife’s body with his to save her from the Joplin tornado and lost his life in doing so. It would be much more surprising to hear a story that happened in the opposite way–where the wife sacrificed her life to save her husband.

It is also still common to hear newscasters and journalists report on an accident or disaster by saying that the death toll included even women and children. Even. Because the death of men is one thing, but the passing of women makes the tragedy seem all the more terrible.

So we know what the practical result of the greater expendability of men is–men have historically been called upon to do society’s most dangerous jobs and have often lost their lives in doing so. But have you ever stopped to think about the effect of this system on the male psyche?

The Chance for Immortality

When Kate and I began to talk about having kids, she asked me why I wanted to have children. I said something like, “I really like the idea of having a part of myself still go on in the world after I’m gone.”

She looked at me blankly.

“What?” I asked. “Haven’t you thought about that?”

She hadn’t. She wanted to have kids because it would be an expression of our love and something to love, and other things revolving around love.

Men have always been particularly interested in the idea of legacy. And who can blame us? In the back of our mind we know we’re expendable, we know that if duty calls, we may have to sacrifice our lives, likely when we are still in our prime, to protect those of the tribe and those we love. At the same time, our primal brains tell us we may never have a chance to be a dad. So a biological legacy is not guaranteed.

And so we turn to creating non-living things, things that will bring value to the world. Time is short, and we want to make our mark and leave behind a part of ourselves. We want just a bit of immortality, and the act of creation, in which a man brings into existence something that did not exist before, is the most godlike thing a man can do. We may blow on and off the earth quickly, but we hope that when we depart, something, however small, is a little different because we were here.

Create More, Consume Less

Of course, even if you’re not buying my personal, more philosophical theory for the origin of a man’s drive for legacy, there are still very practical reasons for the development of this desire.

In the days before settled agriculture, tribes were likely very egalitarian. Women gathered nuts and seeds, and men hunted big game. Anthropologists think that their contributions to the tribe were about equal.

But women contributed something extra: children! So what were men going to do for their extra contribution? Well, if women were handling the reproductive tasks, the men needed to step up and create something extra in the productive realm.

This goes back to what we talked about last time, in that womanhood has always been a status sort of automatically conferred, while manhood had to be continually proven. When a woman had a baby, that in most cases forced her to grow up. But a man needed an external push to propel him into maturity, to keep him from wanting to slide back into infantile dependency. And this is why the mark of a manhood, according to sociologist Steven L. Nock, became whether or not he produced more than he consumed…did he do his part to add value, power, and wealth to society? When he passed from the earth, would he leave the tribe stronger than he came into it? Or was he a lazy leech? Ancient societies around the world were in agreement on this point: the latter was not a man.

The Modern Obstacles to the Drive for Legacy

You don’t hear much about “legacy” these days. There are a few reasons for that.

First, we live in an incredibly present-minded society. There is very little sense of history and understanding of what has come before. There is a sense that our society is the only one that has ever existed and the only one that matters. We don’t have a broad, expansive view of history and time. Because we do not acknowledge the legacy we have inherited, we don’t see the value in leaving a legacy ourselves.

We’re also a culture that wants to believe we can live forever. We venerate youth culture, try to stay looking young as long as possible, hide away our old folks, and shield our eyes from death. The more we deny the inevitability and reality of death, the less motivated we feel to work to create a legacy. After all, who needs to leave something behind if you’ve convinced yourself that you’ll always be around?

Third, we live in an extremely disposable society. Everything is designed to be used a few times and then thrown away. And every advancement is soon replaced by an even better update. And so we lose faith in the idea that anything can truly be lasting. We feel like–why bother?–whatever I can possibly add to the world will soon be obsolete anyway.

Fourth, we live in a very impatient society. We want things to happen immediately. Waiting for our computer to boot up makes us want to punch someone. But building a legacy is a slow process, and more importantly, the results of our effort may take a very long time to manifest themselves…they may not even come to fruition until after we are gone. Talk about an instant-gratification buzz-kill.

Turning the Switch of Legacy in Your Life

“Yet man dies not whilst the world, at once his mother and his monument, remains. His name is lost, indeed, but the breath he breathed still stirs the pine-tops on the mountains, the sound of the words he spoke yet echoes on through space; the thoughts his brain gave birth to we have inherited to-day; his passions are our cause of life; the joys and sorrows that he knew are our familiar friends—the end from which he fled aghast will surely overtake us also!

Truly the universe is full of ghosts, not sheeted churchyard spectres, but the inextinguishable elements of individual life, which having once been, can never die, though they blend and change, and change again for ever.” -H. Rider Haggard, King Solomon’s Mines

What does it mean to leave a legacy? My definition comes from what I learned from Boy Scouts: leave your campsite better than you found it. So it is with life. To leave a legacy means to leave the places you go and the people you meet a little better than you found them.

Many men will likely say that their children are their greatest legacy. And that’s fantastic. But as discussed, I believe men have an innate desire to leave a legacy that touches the broader world around them as well.

Actually, the comparison between children and creating value in the world is quite apt. They both involve a man’s seed. With the former, a man’s reproductive seed, thousands of sperm fight to reach the egg, but only one will find purchase. With the latter, a man’s productive seed, thousands of attempts to create value in the world may end up on barren soil, but a few will hit the mark and sprout new life.

Thus, every man should be a Johnny Appleseed of sorts, scattering their seeds of creation wherever they go, and being content to know that the seeds may not bear fruit until long after they have moved on. It requires patience, and a sort of faith, a faith in the idea that we have not lived in vain, that the world is a little different from our being here.

I was surprised at how popular last week’s Manvotional, Facing the Mistakes of Life, turned out to be; it was shared over 1,000 times on Facebook. The passage came from a book written in 1909 by William George Jordan. Perhaps Jordan’s books were popular in his lifetime, which is a nice reward, but how extraordinary is it that 100 years after penning those words, they would be read by thousands of people on a medium of technology he could not have even conceived of? Sitting at your desk on a rainy day, as you type words into the computer, can you imagine people a century later finding inspiration in your writing? That’s legacy.

And legacy comes not just from the creation of physical and literary objects. A legacy can come from an idea, a business, a tradition, a thought…anything that changes a person, the world, just a little and gets passed on, anything that lasts.

There are lots of little ways to create your legacy. A man never knows when an encouraging word given to another may change the course of that person’s life, and in turn, alter the course of history and add value to the world. Here are a few ways to create your legacy every day:

- Keep a journal

- Start a manliness club at your college or high school

- Begin a new tradition at your fraternity

- Take steps to start your own business

- Start a blog

- Be a mentor–become a Big Brother, coach Little League, take someone new at work under your wing, etc.

- Share your ideas in a Master Mind Group

- Start a Bible Study or small group at church

- Figure out new and better ways of doing things at work

- Make a piece of furniture or another item that you can pass on to your children, and they can pass on to their children

- Start a new program in your community–a rec league, a recycling program, etc.

- Tinker with an invention

What are some other ways a man can create a legacy? What are you doing to create your own legacy?

Switches of Manliness Series:

The Cure for the Modern Male Malaise

Switch #1: Physicality

Switch #2: Challenge

Switch #3: Legacy

Switch #4: Provide

Switch #5: Nature