Welcome back to our series on the 3 P’s of Manhood: Protect, Procreate, and Provide. When professor David D. Gilmore did an exhaustive cross-cultural analysis of how masculinity was lived and perceived around the world, these three male imperatives emerged as nearly universal parts of the code of manhood in every culture. His findings are detailed in Manhood in the Making, and the quotes below, unless otherwise noted, come from that book.

If you haven’t yet, I invite you to read the “Series Sidenote” and Conclusion to the first post in the series on the imperative to protect. Those sections are important in framing what this series is about and the mindset with which it should be pondered.

As we continue on, I want to remind readers that these articles are largely descriptive, rather than wholly prescriptive. That is, they offer a look at the core standards of manhood that are common to almost every culture, but they do not necessarily endorse the idea that every aspect of these standards should be perpetuated. These traditional male imperatives are neither good nor bad in and of themselves; it’s how they’re lived and enforced that matters. I believe a man must first understand these stripped down fundamentals that are common through centuries of masculinity, and then filter them through his moral and religious beliefs to determine their weight in his life.

There is a difference between a cultural concept of manliness and a philosophical one; what Jesus or Marcus Aurelius defined as true manliness can diverge from that which emerged from biological realities, evolutionary pressures, and societal needs and expectations. Or as anthropologist Michael Herzfeld puts it, there’s a difference between being a good man, and being good at being a man. It is the latter category we are grappling with here.

Man as Procreator

The imperative to procreate essentially requires that a man act as pursuer of a woman, successfully impregnate her, and thus create a “large and vigorous family” that expands his lineage as much as possible.

Of the 3 P’s, I think the charge to procreate probably has the least resonance with modern men and will be the most controversial. There are many reasons for this, beyond the fact that “procreate” is a word little used these days, and tends to remind one of an old preacher who employs it as a euphemism for sex.

Proponents of the zero population growth movement will say the imperative to have children is wholly outdated – that while begetting numerous offspring might have strengthened societies in the past, it now has the very opposite effect.

Those who simply don’t want to have children will chafe at the idea that their decision should amount to anything more than personal preference.

Feminists will say that the idea that the man should be the pursuer is sexist, as it has its roots in violence against women and treats them as a prize to be won.

Religious folks, who might otherwise be very receptive to the injunction to “multiply and replenish the earth,” may at the same time be uncomfortable with the fact that in some cultures, it was acceptable to accomplish this charge with a woman who was not your wife, or with multiple wives.

And people of all stripes will likely be uncomfortable embracing a standard for manhood that is not completely within a man’s control. A lazy man can get his butt in gear and become a good provider, and a timid man can bite the bullet and become a courageous protector. But as we shall see below, in many cultures, infertility was always considered the fault of the man, and there wasn’t anything he could do about it.

Finally, unlike the charge to protect and provide, the duty to procreate lacks the same self-sacrificing, heroic quality that stirs one’s “higher” yearnings. It is more base, more biological.

Yes, it would seem that every conceivable segment of our present-day population might have reason to take issue with the idea of procreation as a fundamental male imperative. Yet this charge has been a core component of the code of manhood from the beginning of time, all around the world. In fact, it would be argued by anthropologists like Napoleon Chagnon that not only is the imperative to procreate a fundamental part of the 3 P’s of Manhood, it underlies the other two, and practically all male behavior: a man seeks to develop and demonstrate the smarts and strength needed to be a good protector and provider in order to win a mate and beget offspring with her; once he forms this family, he then strives to continue to provide and protect them. Which is to say, the motivation to provide and protect is often ultimately derived from the motivation to procreate.

Thus, no matter how squeamish a discussion of procreation may make us, its universal inclusion in the global code of manhood demands that we put aside emotional knee-jerk reactions in order to give it a thoughtful examination. It is my hope to provide such a treatment today.

Procreation as a Civic Duty

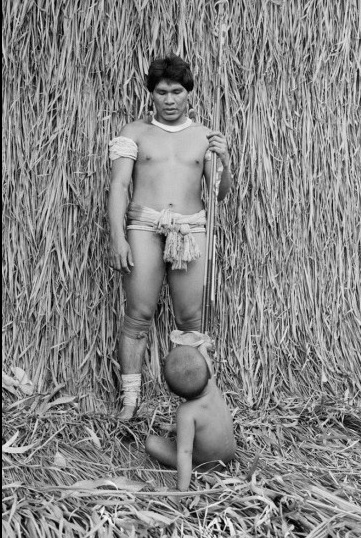

“The birth of his first child is an important event for a Sambia man: it is, ‘de jure, the attainment of manhood.’ To be ‘fully masculine’ a Sambia man ‘must not only marry, but father some children.’ Having many children is one of many social functions that constitute the notion of a cultural competence which directly enhances group security. In impregnating his wife, the Sambia man ‘has proved himself competent’ in social functions. Not so far away, among the Baruya of the Anga territory, a man gains prestige with each succeeding birth ‘until he ‘truly’ becomes a man, that is the father of at least four children.’”

Every society erects standards for manhood that are designed to motivate men to overcome the passivity and timidity inherent in human nature in order to perform the often hard and dangerous tasks that are needed for the community to survive and thrive. A man must demonstrate what Gilmore calls “cultural competence”; he must be useful, effectual – of service to his family and his people. In striving to live the 3 P’s, a man wins honor for himself and gains other benefits as well, while at the same time contributing to society’s collective stability, security, and power. In this way, the code of manhood benefits both the individual and the group. (We’ll explore this dynamic and its implications in a modern world where manhood isn’t honored or valued in a separate post at the end of the month.)

“When home ties are loosened; when men and women cease to regard a worthy family life, with all its duties fully performed, and all its responsibilities lived up to, as the life best worth living; then evil days for the commonwealth are at hand. There are regions in our land, and classes of our population, where the birth rate has sunk below the death rate. Surely it should need no demonstration to show that willful sterility is, from the standpoint of the nation, from the standpoint of the human race, the one sin for which the penalty is national death, race death; a sin for which there is no atonement…No man, no woman, can shirk the primary duties of life, whether for love of ease and pleasure, or for any other cause, and retain his or her self-respect.” -Theodore Roosevelt

Thus, while we moderns tend to think of sex and children in terms of our personal pleasure and fulfillment, in ages past, procreation was seen as a civic duty. The number of children a man beget strengthened these societies on a variety of fronts – the more members a community had, the more hands there were to gather and produce food and goods, and most importantly, to serve as protectors. The size of one’s village, along with its men’s reputation for fierceness, was a crucial deterrent in convincing enemies to not even attempt an attack.

“As among the Trukese and the Mediterranean societies we have looked at, the New Guinea man of respect must spread his seed and multiply. Although these men regard sexual relations with a measure of anxiety…they are expected to overcome these inhibitions and to reproduce sexually, just as they are exhorted to produce economically and militarily, and to take on a commanding role in trading and oratory. Reproduction is not a personal pleasure; it is very consciously perceived as a social obligation and a measure of good citizenship. Given the dangers of Highlands life, especially the hovering military threat, the society needs offspring to endure…The bigger the village, the safer it is militarily: none dare attack a place of many armed men…The stress on reproduction to build up numbers is impressed forcefully upon boys as a civic duty.”

As we will explore more in-depth in the next article, the universal mark of a real man in cultures all over the world was whether he produced more than he consumed – whether he created and added value in all areas of life, or whether he was a parasite, a man who failed “in all the constructive masculine pursuits.” Thus he who didn’t strengthen society by siring numerous children was seen as a weak link, and thus unworthy of the title of man.

But why would men need an extra push to procreate anyway? Isn’t the sexual drive powerful enough that it could be left to follow its natural course? The urge to copulate may indeed be quite potent, but as we shall see, it was also an endeavor fraught with risks from which a man might be tempted to shrink.

Hot in Pursuit

“Sexual shyness is more than a casual flaw in an Andalusian youth; it is a serious, even tragic inadequacy. The entire village bemoans shyness as a personal calamity and collective disgrace. People said that Lorenzo was afraid of girls, afraid to try his luck, afraid to gamble in the game of love. They believe a real man must break down the wall of female resistance that separates the sexes; otherwise, God forbid, he will never marry and will sire no heirs. If that happens, everyone suffers, for children are God’s gift to family, village, and nation.”

Key to fulfilling one’s role as a procreator was acting as the initiator, and that requirement began with the seduction process. In cultures across the world, the man is expected to make the first move, engage in “aggressive courtship,” and not fear rejection as he does so.

If it takes two to tango, how did the charge to initiate courtship and seduction end up at the man’s feet?

Well, the reality of it, even if unpleasant to acknowledge and contemplate, can likely be traced to male anatomy and polygamy.

While a woman can only grow a maximum of a few babies in her womb at a time, as creators of a limitless amount of sperm, the number of children a man can produce is hypothetically limited only by the time he can invest in copulation. Since we are all biological organisms driven to reproduce our kind, and since men generally have more randy-inducing testosterone, it has long been thought (and behaviorally born out) that men have a higher sex drive than women. And a man can hypothetically act on that drive whenever he wishes; since in the sexual act the male is the penetrator and the woman the penetrated, it is possible for a man to not only initiate sex, but to do so without the woman’s consent.

In primitive polygamous societies, because some men had multiple wives, it also meant that some had none, forcing these men to undertake dangerous raids on neighboring villages to rape their women and kidnap soon-to-be brides.

As societies modernized and monogamy became the common standard, men gained a more or less equal shot at finding a mate, and moral and religious codes developed that sought to temper and channel men’s sexual energies towards one woman at a time. Kidnapping and rape were dropped from the wife-procurement process, but the charge to be the initiator remained. As mentioned last time, a fundamental standard of manhood is a vigorous embrace of risk and competition. Thus, besting other suitors to win the heart of a lady, and risking rejection in asking for her hand, continued to be seen as inherently manly behaviors.

What began as a rationale for violence transformed into a chivalrous act; since men were taught to be stoic, and women supposedly had more tender feelings, the man willingly shouldered the risk of doing the asking and potentially weathering the sting of being turned down. It became the gentlemanly thing to do.

A Potent Procreator

“Like fighting and breadwinning, sexual intercourse is thus also a risky business for Trukese men, a question of winning or losing, for the man can either do the job or not, depending on how his organ ‘works’…intercourse is a contest, ‘in which it is only the man who can lose and not the woman.’”

The risks and responsibilities of being the initiator continued in the bedroom. Central to fulfilling the procreator role was demonstrating virility and sexual competence, and this meant both being able to please one lover’s and simply being able to “get it up.”

While there were certainly cultures where a woman’s sexual satisfaction was ignored, in many, if a man was unable to satisfy his lover, his manly reputation suffered. Gilmore writes:

“Fighting, drinking, and defying the sea are not the only measures of manhood. A Trukese man must prove competence in another arena: sex…To maintain face in the sexual act, the Trukese man must be the initiator, totally in command. The success of the sexual act depends entirely on his performance; in every love affair he is sorely tested. Like the Andalusians and the Italians, a Trukese man must be potent, having many lovers, bringing them to orgasm time and again. Interestingly, this erotic ability is, again, phrased in idiom, not of love or charm, but of pure physical competence. If he fails to satisfy her, the woman laughs at him; he is shamed for being ineffectual…And, significantly, his failure to perform is rewarded by jibes and insults that liken him to a baby because he is incapable of performance. The standard insult for a man who performs badly is the advice to ‘take the breast…like a baby.’”

Impotence was considered incredibly emasculating, since it robbed a man of even the chance to please his partner, and more importantly, to attain the culmination of what the sexual act aimed at: fathering children. Thus this malady has been a source of anxiety for men in cultures across the world, right up until the present day. One need only look at the almost comically manly imagery (Working with machinery! Pulling horses through the mud! Making fire!) used in commercials for erectile dysfunction drugs to realize that insecurity over the implications of impotence for a man’s overall claim to manhood remain.

“Many Indian men have been described as obsessively worried about their sexual capabilities…This heightened fear of impotence occurs throughout the subcontinent and is said to be distinctly Indian. In some cases, men adopt special diets to fight impotence and bolster performance. Often these involve both magical potions and the ingestion, in homeopathic fashion, of semenlike fluids such as milk or egg whites or even…semen itself. Fear of virility loss has given rise to more than the usual panoply of cures and treatments for impotence — real or imagined — in both India and Sri Lanka.”

Doing Brave Deeds for My Lady

All of the 3 P’s interact and interrelate with each other, so that, for example, demonstrating you were a good provider and protector could impress the women in your community, winning you opportunities to then show your prowess as a procreator.

Much of the risks men take, the wealth they try to accumulate, and the showy things they do, are, at their core, attempts to impress women, who have traditionally acted as the gatekeepers to sex. Women don’t just serve as passive enticements either, and may actively goad the men into demonstrations of manhood.

For example, among the Samburu, a pastoral tribe in East Africa, cattle are of the highest value as they serve as both a source of sustenance and trading wealth, and the size of a man’s herd is directly correlated to his level of manly prestige. Rustling cattle from neighboring tribes to amass one’s own herd is not only accepted, but encouraged; because cattle-rich men of the tribe are expected to throw feasts in which they share their wealth with their fellow tribesmen, an increase in one man’s herd benefits the entire community.

For young male Samburu (called moran), raiding is seen as an important test of courage, and especially for those “who have little other opportunity to amass animals for breeder stock, raiding and rustling represents the principal means of achieving manhood and all its social rewards: respect, honor, wives, children.”

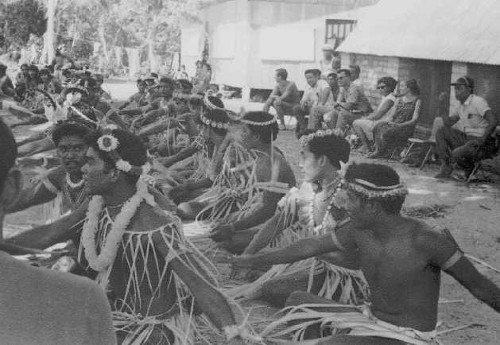

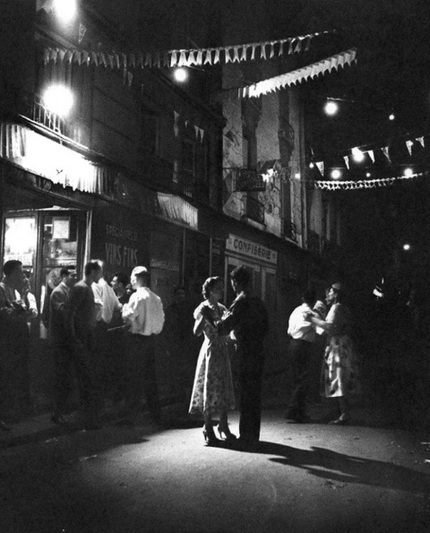

During the tribe’s festive, exuberant dances, the connection between a young man’s willingness to rustle cattle and his desire to impress a potential sexual partner and wife is made crystal clear:

“the nubile girls, standing on the sidelines, sing lilting songs that taunt those moran who have never been on a stock raid. In their finery they chant their lyrics, making galling insinuations of cowardice. Moved by the beauty and challenge of the girls, the boys are whipped into a frenzy of desire. Driven to try their hand at rustling without delay, they impassively take up the challenge. Spencer observes: ‘That the taunts of the girls help to maintain this ideal and induce the moran to steal may be judged from this description of one moran. ‘You are standing there in the dance, and a girl starts to sing. She raises her chin high and you see her throat. And then you want to go and steal some cattle for yourself…You leave the dance and stride into the night, afraid of nothing and only conscious of the fact that you are going to steal a cow.’”

As Gilmore observes, here again we see the way in which the standards of manhood work to simultaneously advance the interests of the individual and the group:

“The way the Samburu moran impress their objects of desire by running risks in foreign lands seems to conform to a virtual global strategy of courting…In Elizabethan England, as among the Samburu, this romantic appeal of “passing danger” in defense of basic values is something that everyone would easily have understood as the mythic confabulation of manhood.

As a collective representation, masculinity often forges an iron shield of protectiveness on the smithy of honor and courage; sexual magnetism follows, as though virility were itself a matter of braving danger to succor those one loves. The connection between virility and civic-mindedness comes out clearly and dramatically.”

The theme of the man who performs brave deeds that win the heart of a woman, while also benefitting the larger community, is ubiquitous in Western myth and literature right up to the present day. Think of the knight who slays a dragon that is terrorizing a whole countryside in order to gain the hand of the princess, or the action hero who kills a bad guy who’s kidnapped his love interest, stopping this evil genius from blowing up the world at the same time.

What About Gay Men?

Homosexuality is such a hot topic these days that I can imagine the elephant in the room for many folks is how being gay fit into this rubric of manhood.

Well, the first thing that’s important to realize is that the idea of “being gay” didn’t exist in most cultures until the 20th century. The term “homosexuality” was in fact not coined until 1869, and before that time, the strict dichotomy between “gay” and “straight” did not yet exist. Attraction to, and sexual activity with other men was thought of as something you did, not something you were. It was a behavior, rather than a lifestyle or an identity. (You can read more on this shift and how it affected male friendships here.)

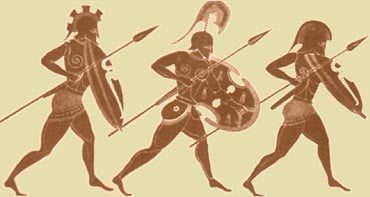

In some cultures, particularly those influenced by the Judeo-Christian religion, homosexual behaviors were condemned. But in many preindustrial, pre-Christian societies, it was considered acceptable for men to dabble in same-sex relationships. This was especially true of warrior societies like ancient Japan and Sparta, as it was thought that a samurai or hoplite who went to war alongside his lover would be a better soldier – apt to be less lonely on the march and to fight more fiercely in battle.

In these cultures, engaging in homosexual sex did not impugn a man’s claim to manhood, so long as he “retained the active role in the encounter.” Accepting “the passive, or receptive role in the sex act,” was considered effeminate, an abdication of one’s masculinity, because it meant “he surrendered the male prerogative of control or dominance.” As the Roman Plutarch puts it in his Dialogue on Love, “Those who enjoy playing the passive role we treat as the lowest of the low, and we have not the slightest degree of respect or affection for them.”

Even though a man could engage in “transient homosexuality” without it affecting his manly reputation, a proclivity for same-sex relations did not exempt him from the charge to procreate with a woman. He was still expected to fulfill the imperative to strengthen his society by producing children. For example, though Spartan warriors could take a male lover while out on campaign, once they returned home, they were expected to sleep with their wives and fulfill their duty of adding new citizens to the state.

Results Matter

“In southern Spain…people will heap scorn upon a married man without children, no matter how sexually active he may have been prior to marriage. What counts is results, not the preliminaries.”

In many cultures a certain amount of wild oat sowing was accepted behavior for young men. But this youthful carousing was not seen as a manly end in and of itself, but only as a means to an end:

“Even in those parts of Southern Europe where the Don Juan model of sexual assertiveness is highly valued, a man’s assigned task is not just to make endless conquests but to spread his seed. Beyond mere promiscuity, the ultimate test is that of competence in reproduction, that is, impregnating one’s wife. For example, in Italy, ‘only a wife’s pregnancy could sustain her husband’s masculinity.’ Most importantly, therefore, the Mediterranean emphasis on manliness means results; it means procreating offspring (preferably boys)…Simply stated, it means creating a large and vigorous family. Promiscuous adventurism represents a prior (youthful) testing ground to a more serious adult purpose.”

With all the 3 P’s of Manhood, public affirmation and concrete proof of one’s prowess is demanded. Whether a society frowned upon fooling around or winked at it, eventually a man had to demonstrate he had moved on from the preliminaries and succeeded in the ultimate requirement of the procreator role — the end goal that all the aggressive courtship, all the braving of dangers in the name of seduction ultimately aimed at: fathering progeny, expanding one’s lineage, and passing on one’s genes.

“Sexual ‘function’…is a passport to acceptance generally as a man and indeed a critical part of the Mehinaku masculinity syndrome that defines adult male status. Like the Trukese, a man who fails to bring his wife or lover to orgasm, fails to satisfy his partner, fails to beget children, is ridiculed and publicly shamed, becoming not just a figure of fun but an outcast in a more inclusive sense.”

A man who cannot pass this final test, who is infertile and cannot father children, is faulted for this deficiency, and given scorn rather than sympathy. For example, in Southern Spain, the man is saddled with full responsibility for sterility:

“Although both husband and wife suffer in prestige, the blame of barrenness is placed squarely on him, not his wife, for it is always the man who is expected to initiate (and accomplish) things. ‘Is he a man?’ the people sneer. Scurrilous gossip circulates about his physiological defects. He is said to be incompetent, a sexual bungler, a clown. His mother-in-law becomes outraged. His loins are useless, she says, “no sirven,” they don’t work. Solutions are sought in both medical and magical means. People say that he has failed at his husbandly duty. In being sexually ineffectual, he has failed at being a man.”

Procreation at Present

What’s interesting to me is that while writing the piece on the Protector duty, it felt natural to use the present tense, while in writing this one, it seemed more appropriate to use the past tense. While Gilmore’s observations on the Procreator role come from anthropological studies done just 40-50 years ago, the expectations and standards surrounding this male imperative have truly changed dramatically over the past half century. At the same time, the fact that strong echoes of these standards persist despite vigorous challenge, tells us how deeply entrenched they really are.

The implications of these changes are numerous and profound, and could all warrant their own articles. For now, I will provide a brief overview of just a few of the most salient issues.

It Takes Two to Tango… Awkwardly

When it comes to relations between the sexes, we currently exist in a state of limbo, where the old “sexual scripts” are hypothetically no longer supposed to be in force, but in practice are still very much hanging around, making for some confused interactions between men and women.

For starters, while girl power campaigns and advice columnists have sought to convince young women that asking a guy on a date instead of waiting for him to do the asking is completely acceptable, many women still second-guess the appropriateness of making the first move. For their part, many young men have voiced their support for a leveling of the dating playing field, though I do wonder how much this willingness to share in the responsibility of asking is truly born of a sincere effort to advance gender equality, rather than sheer laziness and the simple relief of unburdening themselves of the risk of rejection.

In the bedroom, instead of the man having to initiate and take responsibility for the proceedings, women have taken more ownership of their sexual pleasure, with sex being seen by both partners as a more collaborative activity. Yet there remains more emphasis on the man being able to please his lover in popular culture, if only because bringing a woman to orgasm is more of an art, while a woman satisfying a man is more of a straightforward endeavor.

We are told that women are as game for sex as men, and therefore should be able to initiate it without being “slut-shamed.” Some men appreciate this new standard, while others still find it a turn-off when women are too forward with sexual advances, and they are then shamed for having this “throwback” reaction.

In marriage, the man, seeking to be an enlightened, egalitarian partner, and not wanting to be an ogre, tries not to always be the one to initiate sex. But this reticence then leads the wife to worry that she isn’t sexually desirable to him, and to question his manly virility. So the husband starts to initiate more, but his wife isn’t in the mood as much as he is, so he pulls back again, and the cycle repeats itself.

And, as a quite fascinating article in The New York Times recently detailed, even in very egalitarian marriages, where women don’t want their husbands to take charge in any other area of their lives, many do still want to be dominated in the bedroom. But their husbands, used to equally splitting working, diapering, cooking, cleaning and decision making – find it difficult to shift gears and assume this role.

Seduction and love can be a beautiful, delicate dance, a paradoxical art in which the partners are equal, but the man is tasked with leadings the steps. Today both partners are supposed to be on the same footing, which results in a lot of stepped on toes.

Notches on the Bedpost, But None on the Crib

The consequences of the invention of birth control and the sexual revolution on the male imperative to procreate can hardly be overestimated.

Ready and effective birth control allowed the two fundamental and formerly inextricably tied planks of procreation – sex and reproduction – to be completely uncoupled for the first time in history. While men formerly had to accept the responsibility of children if they wanted to enjoy the pleasures of sex, now they could get the milk without buying the cow. In fact, while having children once enhanced a man’s reputation for manhood, now some see the responsibility for offspring as detracting from it; there’s definitely a strain in our culture that celebrates the completely unattached, perennial bachelor (see: George Clooney) as the paragon of manliness.

Has the Cheapness of Sex De-motivated Men?

There is another significant implication of the sexual revolution as well. As mentioned above, since women once served as the gatekeepers to sex, and kept it relatively tightly locked up, men had to strive to show their prowess as protectors and providers in order to woo them into giving up the key. In economic terms, the demand for sex was high and so was the “price,” so that men had to “pay” a lot to get it.

What then would one expect to happen if sex became readily available without much effort? Men would lose the motivation to build up their status. This, some social scientists posit, is exactly what has happened. In “the sexual marketplace,” the male demand for sex has remained the same, but its “price” has dropped dramatically; there’s no need to slay a dragon, just buy a lady dinner and invite her back to your place. The modern “cheapness” of sex, some theorize, accounts for the way many young men are resisting commitment and floundering in other areas of their lives such as academics or career responsibilities.

If you’re interested in this “economics of sex” theory, this well-done video explains it more clearly than I ever could, and uses Sharpies to do it:

Sex: The Overweighed Pillar of Manhood

One of the most interesting insights I got from Manhood in the Making comes from two observations Gilmore includes about an indigenous people of Brazil, the Mehinaku.

First, that:

“probably most important to the Mehinaku as a measure of maleness is sexual performance. The Mehinaku, as Gregor describes them, are unusually preoccupied by sex, the men complaining they can never get enough of it and talking about it all the time.”

And second that:

“The Mehinaku fight no wars and were never warriors. They are self-consciously a nonviolent people, regarding not only warfare but also displays of anger as morally repugnant.”

It seems to me that these two attributes of Mehinaku men are actually quite connected. When one or two of the other P’s of Manhood are weakened or non-existent, greater stress is placed on the remaining pillar(s). And it is usually sex, the lowest-hanging fruit of the manly imperatives, the charge that involves the least amount of risk and work, that endures.

Observe our current culture in the West. In the US, only .5% of citizens serve in the military, so that for the vast majority of men, being a warrior and a protector is more abstraction than reality. And whether it’s because women make up half the workforce, or that jobs are so hard to find, and those that are available are largely of the soft, white collar variety, the impetus to provide has lost much of its manly sheen. So what remains for young men who yearn for manhood? Only sex. While the edifice of manhood is designed to be supported on a triad of columns, all of its weight now rests on the pillar of procreation, and even that pillar is a rickety shade of its former self. Weighted with a load it was never meant to carry, the pillar twists and contorts, leading to perversions of the manly code – men who devote all their energy to becoming master pick-up artists or who stare all day at online porn.

Procreators Are the New Parasites?

In times past, a man who added children to a tribe/village/nation was seen as a producer, someone who greatly added to the overall strength of the group. Those who did not reproduce were considered parasites who used society’s resources but did not replenish them.

Today, there are some who think having children weakens one’s nation and world, by stressing already depleted resources and adding to problems like global warming. These folks would argue that the equation is completely flipped: procreators are now the parasites.

Of course, not everyone agrees that overpopulation is a real danger or that the earth has a set carrying capacity. And in some countries in Europe that are experiencing zero to negative population growth, exhortations (and government bonuses) to have children to strengthen the future of the state can be heard again.

Men Going Their Own Way

Gilmore argues that the 3 P’s of Manhood not only aim to motivate men to perform service to their communities, but also act “as modes of integrating men into their society.” As we’ll discuss later, it may be that men have a harder time growing up and embracing responsibility than women, and the standards of manhood provide men with a purpose that counteracts a natural tendency to live for self and opt out of social involvement.

The imperatives of manhood are only effective in societies that are small enough, or at least homogeneous enough that the dynamics of honor and shame can operate, and men feel a kinship with their fellow citizens. Without such a kinship, a sense of duty and obligation to serve and protect them cannot exist.

For this reason, the nuclear family is in many ways the last bulwark against the dissolution of manliness. In a nation of increasing diversity, where an honor culture can no longer function, a man with wife and children still has a small group he is driven to protect and provide for.

Last time, I compared the protector imperative to the cornerstone of the arch of manhood, since courage has been considered the sin qua non of “real men” in every culture since time immemorial. But upon further reflection, I’d say the duty to procreate is really a better fit for this metaphorical role. Because once the pillar of family crumbles, so does the whole edifice of manhood; without even a tiny fiefdom to provide for and protect, some men will opt out of the traditional duties of manhood altogether.

This is not a hypothetical theory; simply google “Men Going Their Own Way” (MGTOW) and you’ll find a slew of blogs dedicated to the idea that because society no longer respects and honors masculinity, men should no longer strive to meet the traditional markers of manhood. Those who come to embrace the MGTOW philosophy often feel that women today are no longer of a caliber that is worth pursuing and committing to, and that if you do get married and it inevitably doesn’t work out, divorce and family courts are so hostile to men that they’ll chew you up and spit you out. The rational decision then, they would argue, is to avoid marriage like the plague and to live for one’s self, working as little as possible and sleeping around as much as you can.

Many who adopt this philosophy actively hope that by opting out of society, they will help hasten its demise – that in going their own way, they remove one of the columns that’s helping to hold up its rotten structure. Without men propping it up, the thinking goes, our current civilization will crumble and can be reset. Stripped of the ease and luxury that allowed manhood to be denigrated and ignored, people will once again keenly feel how much men are needed, men will be free to men again, and the world can begin anew.

The idea of pressing the reset button on the world can be exhilarating or dread-inducing, depending on your current familial status. For the unattached and unencumbered bachelor, the idea of adventure and chaos might sound quite appealing, especially when compared to his current routine of: wake up, trudge to the cubicle, come home, watch tv, repeat. (The protests around the world these past several years are surely about many political issues. But given the fact that 98% of the protestors are men, I happen to think a lot of it is actually the expression of pure male boredom.) But for the man with a wife and kids, the idea of navigating a post-apocalyptic landscape, trying to protect them from violence and keep food in their little hungry bellies, sounds harrowing – a ghastly reality he’ll fight tooth and nail to avoid.

So, is the family unit the last bulwark against the complete dissolution of manhood, or is it the last remaining obstacle to the world being reset and a culture of manhood returning in full force?

I’ll tell you my answer, from the obvious bias of someone who believes the family is the fundamental unit of society and that nothing can bring greater satisfaction than marriage and children: if you believe in the veracity of the generational cycle, and I really do, a crisis will come that will refresh the world and renew appreciation for manliness anyway. You don’t need to purposefully try to bring it about, so until that wave washes over us, pursue manhood for its own sake whether or not society honors such efforts (yes, there are reasons to do so – stay tuned), live it in your family, and enjoy the fruits of procreation.

There are many more implications for the way that modernity has challenged and transformed the male imperative to procreate. But for now I’ll sign off and turn these issues over to you for discussion. I look forward to reading your thoughtful and civil comments!

Read the rest of the series:

Part I – Protect

Part III – Provide

Part IV – The 3 P’s of Manhood in Review

Part V – What is the Core of Masculinity

Part VI – Where Does Manhood Come From?

Part VII – Why Are We So Conflicted About Manhood?

Part VIII – The Dead End Roads to Manhood

Part IX – Semper Virilis: A Roadmap to Manhood

______________________

Source:

Manhood in the Making: Cultural Concepts of Masculinity by David D. Gilmore

Tags: manhood