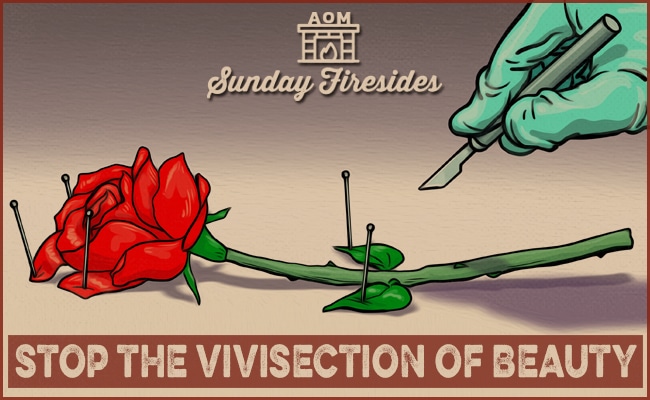

In the 19th century, scientists conducted dissections on live animals to study their living anatomy. Known as “vivisection,” the operations were highly controversial. While some argued that vivisection imparted valuable insights that couldn’t otherwise be gleaned, others felt the additional knowledge the practice produced was negligible, especially when weighed against the cruelty involved in harvesting it.

While medical vivisection is almost entirely banned today, it continues to exist in another, similarly questionable, form.

Modern scientists spend thousands of hours and millions of dollars seeking the beating heart of once-ethereal concepts like love and happiness.

Yet when we hungrily gobble up the results of these sophisticated studies, we find that their insights are somehow less illuminating than those produced by poets and philosophers millennia ago. They merely reaffirm what we already intuitively know. Or would intuitively know, if our aesthetic, reflective qualities hadn’t been allowed to atrophy.

When we don’t apply our hearts to understanding, and rely exclusively on academic explanations to plumb life’s depths, something fundamental about the Good and the Beautiful becomes lost to us.

We know the most effective way to communicate in a marriage, but can’t explain why we wanted to be wedded in the first place. We know how many hours it takes to make a friend, but can’t express what it’s like to intertwine our soul with another’s. We know which part of the brain lights up when we have a religious experience, but don’t understand how to satisfy our yearning for the transcendent. We’ve studied the formula for happiness on paper, but struggle to make it add up in our lives.

The more we measure and quantify the mysteries of meaning, the more they seem to elude us.

Because amidst our probing dissections, we forget one crucial thing:

The subject of vivisection always dies on the table.