Many of our goals in life — from losing weight to saving more money — require willpower. But what is willpower anyway, why does it feel like it fails us so often, and what can we do to make better use of it

My guest today explores the answers to these questions in her book: The Willpower Instinct: How Self-Control Works, Why It Matters, and What You Can Do to Get More of It. Her name is Kelly McGonigal, and she’s a psychology professor at Stanford. We begin our discussion discussing what exactly willpower is, how it can be described as an instinct, and what goes on in your brain when you utilize it. We also unpack the idea that there are really three different types of willpower: I won’t power, I will power, and I want power, and how these powers can be increased.

We then spend the rest of our discussion digging into the limitations of willpower, so we can avoid putting ourselves in situations where it’s likely to fail us. We talk about how shame, the people who surround us, and even, ironically, making progress with our goals, can all lead to the sapping or loosening of our willpower. We end our conversation with Kelly’s best tips for getting the most out your willpower.

Show Highlights

- Why is willpower an instinct?

- What’s going on in our brain when we exercise our willpower?

- Why we usually associate willpower with “won’t” power

- The individual nature of willpower strengths and weaknesses

- So, can we strengthen the weak parts of our willpower?

- The willpower challenges of parents and caregivers (and why it’s not always noticeable)

- The power of exercise and diet (and the chicken and egg problem those present)

- Why your mindset matters so much when it comes to your willpower

- How does our willpower sow the seeds of our failure?

- Why does moralizing sometimes hurt us?

- De-mythologizing self-compassion

- A couple things you can start doing today to better manage your willpower

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- Why Emotions Are Better Than Willpower in Achieving Your Goals

- 5 Willpower Habits Every Man Should Develop

- What is Willpower?

- How to Strengthen Your Willpower

- Restraints vs. Constraints

- Motivation Over Discipline

- Your Life Explained Through Dopamine

- Taking Control of Dopamine

- 22 Ways to Get a Better Night’s Sleep

- How to Establish an Exercise Routine

- The 10 Best Ways to Make Exercise an Unbreakable Habit

- Meditation for Fidgety Skeptics

- Embracing the Grind

- The Importance of Developing a Growth Mindset

- Good Shame; Bad Shame

- Be Less Disciplined

- The Joy of Movement — Kelly’s upcoming book

Connect With Kelly

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Recorded on ClearCast.io

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

The Strenuous Life. A platform designed to take your intentions and turn them into reality. There are 50 merit badges to earn, weekly challenges, and daily check-ins that provide accountability in your becoming a man of action. The next enrollment is coming up in the September. Sign up at strenuouslife.co.

Indochino. Every man needs at least one great suit in their closet. Indochino offers custom, made-to-measure suits for department store prices. Use code “manliness” at checkout to get a premium suit for just $369. Plus, shipping is free.

Progressive. Drivers who switch save an average of $699 a year on car insurance. Get your quote online at Progressive.com and see how much you could be saving.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another addition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. Now, many of our goals in life from losing weight to saving more money require willpower. But what is willpower anyway? Why does it feel like it often fails us and what can we do to make better use of it? My guest today explores the answers to these questions in her book, The Willpower Instinct: How Self-Control Works, Why It Matters, and What You Can Do to Get More of It. Her name is Kelly McGonigal and she’s a psychology professor at Stanford University. We begin our discussion discussing what exactly willpower is, how it can be described as an instinct and what goes on in our brains when we utilize willpower? We also unpack the idea that there are really three different types of willpower, I won’t power, I will power and I want power, and how these powers can be increased.

We then spend the rest of our discussion digging into the limitations of willpower so we can avoid putting ourselves in a situation where it’s likely to fail us. Talking about how shame, the people who surround us, even ironically making progress with our goals can all lead to loosening our willpower. We begin our conversation with Kelly’s best tips for getting the most out of our willpower. After the show’s over check out our show notes at aom.is/ you know it, willpower. Kelly joins me now via clearcast.io.

Kelly McGonigal, welcome to the show.

Kelly McGonigal: Thank you for having me.

Brett McKay: So you are a psychologist that has spent her career, you spent your career researching, writing about, teaching, I’d say about how to help human beings live a flourishing life. And one thing that’s undergirded all of that is this idea of willpower. In fact, you teach a class at Stanford about willpower, and you wrote a book called The Willpower Instinct. That’s what we’re going to talk about today before we get into what willpower is because I think a lot of people have a vague idea of what it is. They know it’s the thing that helps them do good habits and stop bad habits. But how did you get started researching willpower? Was it one of those researches mesearch type things?

Kelly McGonigal: Oh. Yes. That’s actually true. But the reason that I decided to teach a class about it originally is as you said, I am dedicated to sharing science that psychologists maybe know about, but the general public doesn’t. Science specifically that will help people deal with challenges or reach their goals. And I remember maybe about 15 years ago there was a survey that the American Psychological Association did that asked people what’s the number reason you aren’t reaching your goals, and not having willpower was one of the most common responses. And I got really interested in that because there was a burgeoning field of research, it was actually on what researchers were calling willpower.

And it seemed to be offering all of these fascinating insights about how it works, and more importantly what we can do to get more of it so that we can reach our goals. And I thought this is science that the public needs to know. So that’s what kick-started the class that I taught at Stanford. And it’s been a great process over the last 15 years of sort of working with real human beings to figure out what is the science that does help people, and how can we apply that science to our own lives?

Brett McKay: Yeah. I think it’s interesting. Just even the anecdotes you gave in the book. And again, this was 10 years ago. What’s interesting about willpower is that can go into different directions. You give anecdotes of people who used things you talked about in your class to get their eating in order. Their finances. It can go in a whole bunch of different directions.

Kelly McGonigal: It can. Actually, I would love to talk about this for a second because when I first taught the class and when I wrote the book, people were very reluctant to be, I think, honest about their biggest willpower challenges. And so I allowed myself to also talk about food mostly, money, finances. Things that we commonly think of as being big willpower challenges. But I actually got an e-mail this week from one of my students in this course and other courses at Stanford, and she was talking about using the ideas from that class to help her get through a medical procedure that without which, she would not have been able to get a diagnosis that is now leading to serious treatment. And having to deal with that panic of wanting to run out of the room because this is a terrifying experience. But I know I need to do this because it matters. This is a moment that matters. And I’m going to choose knowledge. I’m going to choose my health. I’m going to choose courage.

And now that this book has been out there for a little while and I’ve been talking to more people, I am so heartened by the fact that actually people feel more willing to talk about willpower challenges that aren’t the obvious things like, oh it’s so hard to resist cheese which is the default everyone goes to. And talk about things that sometimes are a real source of suffering in people’s lives. It’s that gap between who you want to be and what you find yourself doing and how you spend your time and who you are. And that’s what I’m really interested in. It’s really about how you can make choices. And this is how I define willpower. How can you make choices, and take actions that are consistent with your highest values and your strongest goals, even when it’s difficult, and even when some part of you is exhausted or terrified or distracted?

And that can include a lot of things beyond what we typically think of as willpower challenges.

Brett McKay: Yeah. It could be your … the health example is one, like having to deal with a health scare. But like a marital problem is another one. Something, if you’re a parent, something’s wrong. The kid’s got a big issue with school or they’re doing drugs. How do you manage that and you’re often going to be relying on willpower to do that.

Kelly McGonigal: Yes. In fact, actually I think caregiving and being a parent. Parents are constantly using willpower but because they’re so strongly committed to the goal and the value, they love their kids. It feels more natural. And sometimes we don’t even give ourselves credit. People are not given credit for the fact that they’re doing these amazing things that take courage, take energy, take strength, take self-control, but because it’s in service of a role that we sort of expect people to be committed to or that feel very important to us, we don’t recognize that is willpower. And part of what I try to help people do is figure out how to apply that same sort of natural instinct to do what matters most and to find the energy and the reserves to do it and apply it to your own goals as well.

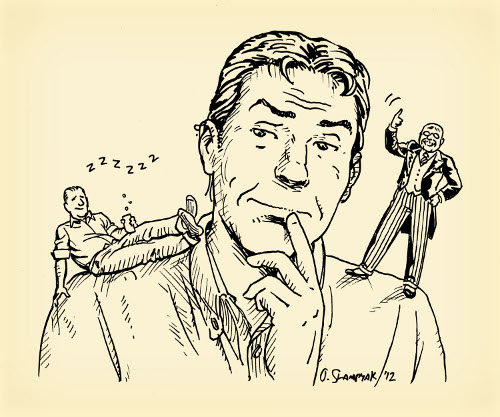

Brett McKay: Well, and so it’s interesting. You called willpower an instinct, and the book is called Willpower Instinct. That word instinct, we typically associate with, in humans at least, those impulsive desires that we have that are like animal-like, right? The instinct for sex or for food. We don’t really think of willpower as an instinct. That’s like, well that’s the prefrontal cortex. That’s like human being stuff. You have to work for that.

Kelly McGonigal: Well, yeah. But let’s just be clear the two instincts that you mentioned. Food and sex. These are things that we need to survive. That’s why we have those impulses. And we have a natural human capacity to do the things that keep us alive and that keep our tribe alive. And it turns out that willpower, self-control is one of those things, too. And I use the word instinct because instinct means a natural capacity that is not necessarily always triggered but it’s part of what it means to be human. Humans are born with this capacity. We have a biological and develop a psychological capacity to think about the consequences of our actions and to remember our values and goals and to plan, and to maybe to suppress or repress other impulses that are getting in the way of our bigger goals.

And again, that’s part of what it means to be human. It’s one of the core features of the human mind and even sort of the social nature of our species. We have to learn how to tolerate conflict. It’s part of what helped humans survive as we became a cooperative species. And one way to think about willpower is, willpower is about applying that same instinct and capacity to negotiate a conflict when the conflict is in yourself. And part of you wants to do one thing, like give into immediate gratification, and another part of you is thinking about maybe your long-term interests, or maybe even a bigger than self-interest. So maybe thinking about your family, or thinking about some cause that you care about. And how do you negotiate that conflict so that you don’t feel like you’re totally neglecting either part of yourself, but that you’re marshaling your most important energy and resources toward the thing that at the end of the day, you’re going to be most glad you chose.

Brett McKay: So those instincts for like, those base instincts for food and sex and whatever, they work in tandem it sounds like with the willpower instinct?

Kelly McGonigal: Yeah. And you wouldn’t want one instinct to completely override the other. Sometimes hunger is the most important instinct and it’s not self-control to deny hunger if the consequence is you starve yourself. And I think that sometimes we get so hung up on these ideas about aspects of ourself that we judge or we think we need to get rid of in order to be our best self or to live a good life, and actually, I’m fascinated by all of the aspects of human nature. Even the things that we sometimes judge like aggression or hostility or the desire to get into immediate gratification. They’re all survival strategies, and we get into trouble when we don’t have a big repertoire of survival strategies when one kind of overrides all of our other human impulses.

So I think that’s one of the great things about taking a scientific lens on this is that it can also free us up a little bit to better understand what it means to be human so that we understand our willpower challenges. They don’t reveal what sort of fundamentally broken or weak about you. They reveal that you’re human and we can study ourselves and better understand ourselves so that we can use all of our aspects of being human to reach our goals.

Brett McKay: So what goes on in our brain when we exercise our willpower? Because we’ve had guests on the podcast talking about dopamine for example. That’s sort of the reward seeking neurotransmitter that that’s what causes us … that’s what makes drugs or surfing the web or eating whatever that delicious thing is makes it desirable. Are there similar things going on in our brain that allow us to exercise our willpower?

Kelly McGonigal: This is a very complex answer.

Brett McKay: Sure.

Kelly McGonigal: And I need to actually describe different types of willpower, probably, to go into what’s happening in the brain. Because I think most of us, our initial idea of what willpower is, is it’s what I would call, won’t power. That is some part of you wants to buy something or drink something or say something that you might regret later, and so some other part of you has to override that impulse. I think that’s sort of what you’re talking about. And you can see that in the brain, actually. So if there’s somebody who has a goal to not smoke and they see someone else smoking and they feel that craving, the brain will start to initiate this whole motor pattern of trying to reach for a cigarette and create the strong desire for a cigarette and even create in your brain stress and anxiety that it will maintain until you give in to the temptation.

And in order to have won’t power in that moment you do need … often it’s areas of the prefrontal cortex, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex which will remind you of your longer term goals like living a healthy life and not getting lung cancer.

Being a good role model to others. Whatever those values are. And the part of the brain, often the left side of the prefrontal cortex that starts to suppress the desire to reach for a cigarette or starts to calm down the anxiety in your brain. So that’s one side of willpower. And what you see is this complex negotiation of different systems of the brain that have different goals. But won’t power is just one side of willpower, and the other two powers that make up willpower are willpower as in I will do this. I will do the thing that makes me scared. I will do the thing even though I’m tired and I want to stop. I will do the thing even though I’m not sure if I’ll succeed. And so part of me wants to avoid it so that I don’t make a fool of myself.

I will do it. I will find the energy, the courage, the determination. I’ll make it a priority. And when that’s happening in the brain, it often looks a little bit different. So for example, you’ll see more activation of the left side of the brain which will be sort of pushing you or motivating you toward action. You will see increased levels of activation in the reward system that make you think, “If I do this, something good will happen.” You might see increased levels of dopamine that are actually driving you toward positive action rather than driving you towards giving into your impulses. And it looks in the brain like courage. It looks in the brain like hope. Sometimes people refer to it as the hope circuitry of the brain, and that looks really different than when you’re trying to suppress an impulse that you don’t want to give into. And one of the things that you see in both of those types of brain patterns is the activation of what I call, I want power.

And this is the thing that really drives our ability to exert I will power, or I wont power. And that is, it’s the power to remember in moments of a conflict what did you really care about? And what you really care about if you were in a contemplative mood and you were thinking about your priorities in life and who you want to be. Because of course, in moments when you’re overcome, say, by a craving, you might say, “What I really want is to give in to it.” So we have to sort of take a different time perspective here. And this turns out to be a strength as well, and it turns out to be a pattern of brain activation, when you ask people to remember what their values are. What their deal breakers are. What their long-term goals are. When people think about who they care about, which is often a great source of willpower. Wanting to support others or wanting to be a good role model for others can be a tremendous source of willpower.

You see this activation in parts of the brain that remind you of those values and goals and it gives you a kind of energy that that then drives whether you need to slow down or whether you need to step up and take action. And when you understand those as sort of the three fundamental powers of willpower, you realize that you can’t exactly say, “This is what willpower looks like in the brain”, because willpower asks different things of us depending on whether we are trying to be the sort of brave version of ourselves or the restrained version of ourselves.

Brett McKay: And it sounds like too, that someone could have … like be really good at I will power, but weak on I won’t power. I’m thinking of like artists, right?

Kelly McGonigal: Yes.

Brett McKay: These are the kind of guys who can just spend all night-

Kelly McGonigal: An athlete.

Brett McKay: … days without … Or athletes, right? But then they have like … sometimes they’re alcoholics or they do drugs. They can’t stop that, but they have that willpower to do what they really, really want to do.

Kelly McGonigal: Yes. And I’m exactly the opposite, right? So my greatest strength certainly is the I won’t power. I’m pretty good on that aspect of self-control, and I’ve had to much more develop the other two aspects. And I think again, this gets into … I mean, one of the reasons I think it’s nice to talk about it in this way is that we can all recognize our willpower strengths. So sometimes you might look at an individual and say, “Oh, that person is out of control with the way that they are free with their speech or their spending or …” People will make these judgements and not necessarily know what’s going on in their insides and how much courage it takes to get out of bed in the morning. Or how incredibly motivated and driven they are in some aspect of their work or their goals.

We all have these different strengths and sometimes our struggles are a little bit more apparent than the strengths that we are implementing in our daily lives and particularly because they might not be how we define willpower. It doesn’t take a tremendous effort for me, say, to eat healthy. There’s a lot of things sort of in me that naturally pull me in that direction. But boy, do I have to work hard to overcome things like my fear of flying. And somebody might look at me and my lifestyle and say, “Wow, she’s got so much willpower.” If they were using these measures of things like healthy behaviors as opposed to in my life when I’m out of control with my willpower it’s more about avoiding things that I don’t want to do or that feel overwhelming.

Brett McKay: Got you. So this idea of we can have strengths in certain types of willpower, weaknesses in other. Does the research say that we’re able to strengthen those weak parts of our willpower whether it’s won’t power, I want power, or I will power?

Kelly McGonigal: Yes. Absolutely. And it almost is … it depends on sort of where you are in your stage of life. Sometimes people ask about kids and how do you develop willpower in children. And then that might be a different question than okay here I am at say, mid-life, and I’m still struggling with X, Y or Z. Is it too late for me to develop self-control in that area? And I like to kind of separate them out because if you think about willpower as an instinct, we know it’s supposed to flourish in us if the environment is right, and if we have all of the things in our contacts that humans need to thrive. So when you look at it from a developmental point of view, kids are most likely to naturally develop in their own time the different willpowers when they’re in an environment that supports their goals and that is relatively safe and trustworthy.

I mean, not like being in a bubble or a cocoon but that in general, kids growing up feel like they don’t have to be vigilant every moment to the possibility that they can’t trust other people and resources are scarce, and you better take what you can get now because who knows what’s coming tomorrow. In that context, kids typically naturally develop these different willpowers. And when you look at it as adults, often it’s a result of what we’ve practiced and what’s going on in our environment that may be pushing different buttons. So when it comes to strengthening willpower as adults, it may not necessarily be about having a trusting relationship with your caregiver or being in a school environment where people encourage you to pursue your own goals. But it’s about how well are you able to create that context for yourself, and to be that kind of support figure for yourself. So to be like a leader of yourself in your own life.

And then we know once you’ve set that goal, there’s lots of things you can do to develop the different powers.

Brett McKay: Yeah. And we’ll talk about that here in a bit. But before we do, so 10 years ago there was this idea that willpower is like a muscle. That we have this finite amount of willpower. And then recently there’s been research saying, “Well, maybe not.” Is that analogy still useful, that we can strengthen our willpower like the same way we strengthen our muscle? Or what is your take on the new research about that?

Kelly McGonigal: Yeah. I do think it’s still an incredibly useful idea and there’s been a lot of debate in the field about specific methods and specific findings that are really about experimental research in the laboratory. If you try to get people to deplete their willpower with a task that it’s never as hard as what we’re dealing with in everyday life. Maybe it’s like resisting a brownie that’s on the table. Or it’s about trying to tune out the TV that is in the corner of the room and you have to do some written task.

There’s a lot of controversy around whether this idea that willpower is limited, that when you use it you get exhausted. But that if you use it enough and in the right ways and you are really taking time to recover, for example, with enough sleep which is really important for the whole willpower system, that actually you get stronger over time. That idea, I still find it to be one of the most useful ideas for people who are interested in increasing their willpower, even though there’s been this interesting debate and some challenges with the experimental research. And I think people who pay attention to their own lives will immediately see how this is true in their own lives. The first tenant is that you can’t control everything you think, feel, say, do, and consume.

We don’t have that kind of energy reserve to constantly be trying to perfect or suppress or plan every action to whatever some sort of ideal is. It’s exhausting. And we know that people who, for example, work in professions where they are allowed to show what they’re really thinking or feeling. I’m thinking about people who maybe work in customer service or work in healthcare where they’re constantly trying to put on a good face and are dealing with a lot of stress and maybe even hostility from other people. That’s exhausting at the end of the day and anyone’s who’s listening who’s ever worked in that sort of role, you know what I’m talking about.

The same thing can be true for parenting or caregiving. When you’re taking care of someone who’s sick. Or you’re trying to sort of control your emotions so that you can be the best version of yourself as a partner, as a spouse, as a parent. It can be exhausting. And then, if at the end of that experience, when you’re feeling most exhausted, someone says, “Do you want a pizza, or do you want a salad?” It’s not that surprising that sometimes we just want something that is going to make us feel good in this moment. That feels like a reward. That feels comforting. Or if we’re asked in that moment now do you want to do this next really hard, difficult thing, we might be like, “No. Because I’ve done the difficult thing. And I don’t have anything left to give.”

So I think that idea is incredibly useful for two reasons. One, because if you’re interested in supporting willpower sort of in our culture, helping people be the best versions of themselves, we need to recognize how we may be undermining that through certain systems or policies or our culture, and understand that if you want people to be the best versions of themselves, you can’t constantly be asking them to sort of take on the challenges of others and suppress their own feelings or their own instincts and impulses.

But the other is, it can help us feel more human when we experience that type of exhaustion or what researchers would call depletion. That it doesn’t mean that you are a failure of a human being because you can’t do it all, all at the same time. So there’s that idea. And then the second aspect of the model which is also super useful is that if there’s a specific willpower challenge that you’re facing, like you’re trying to quit a substance that you use regularly, it is not always going to be as hard as it is in this moment. That we do develop strengths and habits that support us in making a lasting change over time. Whatever is the hardest thing for you right now, if it’s really important to you, what the strength model willpower says is, “Your brain will change in ways that support this. Your nervous system will change in ways that support this. And you’re going to be able to construct in your home, your workspace. You’ll build relationships that support this over time.”

And it’s this growth mindset that I think when you combine it with an understanding that we can’t control everything all the time, so you might need to make some choices or you might need to let yourself off the hook and understand why certain things are difficult, and at the same time if you have an incredibly important goal to yourself, and this is a change you want to make and it is so hard to know it will not always be that hard. Those are the two ideas that are worth saving from whatever’s going on with this kind of replication crisis in the experimental research.

Brett McKay: Yeah. And I think the idea too that you can strengthen your willpower, yeah. You just said it gives people a sense of agency, a sense of autonomy that they can do something. Like if you’re physically weak, you know you can start lifting weights to get stronger knowing that hey, if I sleep more, I’ll have the ability to sort of pause and plan better. You talk about research that we’ve had researchers on about meditation. That can help self-control. It’s not like a game changer. It’s not like if you start meditating you’re going to be like super disciplined, but it helps. It’s something you can do. Other things, just exercising. Physical exercise can carry over to other aspects of our life when we’re trying to exercise willpower, whether it’s the I won’t power or I will power.

Kelly McGonigal: I know. And it’s so funny because you’ve mentioned three things now. Sleep, meditation and exercise that are often the willpower challenges people come to me with. So when I teach the class I always have people pick a challenge they want to focus on. And so I do feel a little bit guilty when people are like, “What can you do to most effectively strengthen your willpower?” And I’m like, “Well, you should exercise.” And people are like, “What? That’s what I need the willpower for next.” I’m like, “Well, you can meditate.” Like, “Oh please.” So, I understand that sometimes when people hear those … of course one we could add to that is eating a diet that helps you keep your energy levels pretty solid. Like that also helps and there’s some interesting research that a diet that maybe keeps your blood sugar levels steady or a diet that includes a lot of plant based foods actually changes the physiology of your nervous system to help you better handle challenges and stress in a way that supports willpower.

But once again you tell people, “Eat a healthier diet will give you more willpower.” And it seems like a chicken and egg problem. So often when it comes to these things that we know … one thing they all have in common is they’re changing our biology and they’re changing our … whether it’s a neurobiology or a biochemistry or what’s happening with our cardiovascular system and immune system, they all play a role in whether or not we have willpower. Inflammation in your body can suppress willpower because it alters the way that your brain functions. We know that exercise can influence your willpower by altering your cardiovascular system and how that interacts with your autonomic nervous system in ways, I think, give you more or less willpower. And there’s something like … it’s just profoundly biological and physiological and it’s connected to the fact that human beings are biological creatures and willpower is an instinct that’s related to how our biology works.

So I always tell people, “Pick the thing of those things that I mentioned. Get better sleep. Be physically active on a regular basis.” I mean, there’s some research showing that even five minutes on a treadmill will boost your willpower. We’re not talking about you having to dedicate three hours a day to exercise if that’s not realistic. Eating a diet that to you, you can feel it’s giving you energy, or meditating for, again, a few minutes a day which changes what’s happening in your nervous system and your brain.

Just do the thing that seems the least difficult or the least aversive. And you’re starting this upward spiral which then makes all of the other things easier to whatever degree you want to engage with them.

Brett McKay: Right. You don’t have to grit your teeth and just force yourself to do it. You’re actually saying, “Actually don’t exercise your willpower too much to strengthen your willpower”, because it will come with time.

Kelly McGonigal: Although, if you do, it’ll be … as long as you view it … So this is the interesting thing. If you view something difficult as in service of your general willpower, it’s more likely to generalize. So even if you do have to grit your teeth to go for a walk or to sit down and meditate and breath for five to 10 minutes, if you feel like you’re gritting your teeth, but at the end of it, you acknowledge I had an intention, there was a part of me that didn’t want to do it and I did it anyway. And you acknowledge, I just flexed my willpower muscle. Research shows that type of mindset helps us generalize our strengths so that the next willpower challenge you face which might be trying to control your temper at work, or it might be choosing not to get drunk at an event. Whatever that willpower challenge is, in that moment you’re going likely to have remembered, okay this is what it feels like to feel that conflict and I know I have the strength to make this decision now as well.

Brett McKay: So what’s interesting about the rest of your book, the first part you talk about what willpower is, what’s going on in the brain and then that we can strengthen our willpower by some of the things we just talked about. But it seems like the rest of your book is talking about the limits of willpower so that you can avoid situations where you’re going to set yourself back despite all the willpower you exercise. And it’s some really interesting research that comes out of that. For example, this idea of moral licensing. You have a whole section to this, right? Where our willpower can actually sow the seeds of our failure, right? Because of moral licensing.

So what is moral licensing and how does our willpower, like our … our efforts to be good can backfire and actually cause us to fall short?

Kelly McGonigal: Yeah. So moral licensing is an example of these funny cognitive traps that humans get into where we end up sabotaging our own goals. So moral licensing is basically, it’s when you do something that is consistent with a goal and so you give yourself credit and that feeling good, like, ah, I did that thing, for whatever reason human beings tend to what to then give themselves permission to do the other thing. And people will often make a choice that is not in their best interest because it’s like we’re keeping some sort of score card. I was good this morning, so I can be bad this afternoon. So an example would be, let’s say I saved some money when I went food shopping, so now I feel like I am licensed to splurge and spend a little bit more money at lunch.

Or maybe I went to the gym this morning and I feel really good about that, feeling like I’m a good person, and I give myself the credit, and then I spend that credit by eating a second helping of dessert. And the idea of moral licensing is, it’s not a problem to reward yourself for doing things that are consistent with your goals. The problem is, we so often … we try to like balance it out. We forget what our actual goal is. And we engage in a reward that actual is sabotaging a goal that is deeply meaningful. So I definitely don’t want to imply that you shouldn’t encourage yourself when you make progress on your goals. You should just ask yourself, “Is this reward I’m giving myself, is it literally taking me backward to sort of undoing the progress that I made?”

And part of the problem with this is that we use these terms, like I was good, and so now I’m going to give myself a treat as if we’re children who need to be bribed for doing anything at all. And it really takes us further away from that autonomous motivation that says, “Hey, the reason I chose to save money this morning is because I’m working toward financial stability. And I want to get out of debt. That’s my actual goal.” And when you’re connected to that, you’re less likely to say, “Now that I’ve been good, I can let myself off the hook and spend a little bit more money here.” A lot of time it’s about commitment and do we actually understand what our commitment is? Or are we engaged in this weird sort of moral accounting system where we like to go back and forth between being the good version of ourselves and then naughty version of ourselves? Or the indulgent version of ourselves?

Brett McKay: And really this idea of moralizing our willpower, so like we tend to do that. Particularly in America. I guess it’s that Protestant work ethic, Puritan roots that we have, right? A lack of exercising willpower is a moral failure. But you highlight research that shows when you think of willpower in terms of morality, if you don’t exercise it you are morally bad. It can actually make things worse. How so?

Kelly McGonigal: It can. One of the reasons is is because it triggers feelings of shame. So you used the example of exercise. You could think of any number of reasons that somebody might want to be more active. Maybe they’ve heard that exercise is a really good treatment alongside antidepressants for mental health which is true. Maybe they want to improve their health. Maybe they want to have more energy. Maybe they want to sleep better. All these different actual positive outcomes you could get from exercising. And then as soon as we turn it into so if I’m being good, I will exercise, as soon as you don’t have time or as soon as you wake up and you’re feeling sick and you don’t have the energy, now all of a sudden you’re bad because you didn’t exercise.

And then people can feel the type of shame that makes them say, “You know, what’s the point of this? I’ll never be able to meet this goal. I might as well give up now.” Shame is one of the most willpower depleting physiological states in the mind and in the body. It basically is like, it’s like putting on all the breaks. Anything good that could happen, shame is like not going to happen now. And it also, it backfires because it makes us forget what our actual motivation and there’s so much research on this. I’m not against morality. I’m not saying go out and try to be immoral. It’s almost like it’s adjacent to what the conversation should actually be. That it should actually be about what you want, because if we’re defining willpower as the self-control to do what matters most to you, it’s not about whether I think you should exercise or I think you shouldn’t smoke, or I think you should be out of debt, or I think you should control your temper.

It’s not about me outside. It’s about you and what you want in your life. And willpower is basically, are you able to make choices in the context of your life that get you closer to the life you want to have, and the outcomes that you want? And if you can remember that instead of going into this moralizing, there’s this natural energy that can support you in reaching your goals, even when you’ve had a set back, or even when you’ve made progress and you’re starting to fall into that trap, maybe of moral licensing. You’ll know what you really want and that’s why I always tell people of these three powers, if there’s one you want to strengthen first, strengthen the want power so that you don’t fall into some of these cognitive traps like moral licensing.

Brett McKay: Yeah. The moralizing backfiring, you see that a lot with diet because people eat like a cookie and they’re like, “Well, just ruined my diet. Might as well just eat that … I don’t know. Double quarter pounder with cheese. It’s already ruined.” Like that’s kind of when you think about it that way, yeah …

Kelly McGonigal: What did you ruin? It’s what you ruined is your sense of your self as I guess like a good person making progress today. But if you actually look at every choice you have as a new beginning, which it is, it’s … the outcomes you get are consequence of the cumulative effect of our choices. Every single choice you make is a kind of a blank slate where you can either get yourself closer to or further away from your goals. This whole idea that like what’s the point, I’ve already messed up, that it doesn’t mean anything when you’re really clear and rational about wanting to make decisions that get you what you actually want.

Brett McKay: And the other place that this stuff can trip you up at is when you think of things like oh well, I ate good food, therefore, I’m a good person. Just thinking about the idea of doing those things can make you feel good which will somehow weirdly cause you not to do the thing you actually need to do.

Kelly McGonigal: Yeah. There is a lot of weird offshoots of the licensing literature. Like vicarious licensing where if you see somebody else do something quote on quote, “good”, you feel virtuous too even if you didn’t do it. If you see someone else exercise you’re more likely to eat more later as if you caught. The whole thing is kind of ridiculous and silly. But I should say one other thing about why moralizing is not a great idea. It’s because it leads us to judge others as well in a way that is I think runs counter to how humans actually work and so we look at others. We make judgements about them based on their behavior. Or their health, or their debt, or their struggles with addiction.

We think we understand something about them because we’re so used to blaming and shaming ourselves. We project that out onto other people. And that in itself is an additional harm. It’s like this whole circle of shame and blame where we moralize ourselves and we judge others. And it’s this whole system we get stuck in where we are failing to recognize why a lot of these things are difficult.

And not turning towards the resources that make change easier. So it’s often what we’re doing to ourselves and also what we’re doing to others including people we care about. And the same things that don’t work for you do not work when you try putting them out on other people like shaming other people for being bad. For not being able to make a change in their lives.

Brett McKay: So yeah. It sounds like the antidote to this then is okay, focus on what you want, right? What the ultimate goal is. But it also sounds like practice some self-compassion. Compassion for yourself if you slip up, but also compassion for others who have also slipped up.

Kelly McGonigal: Yes. And not only for people who’ve slipped up, but also for people who are clearly struggling. One of the things that if you spend any time with people who are recovering, in recovery for any sort of addiction, what you realize very quickly is that, that person when the height of their addiction is able to stay sober for one day, one hour, one minute, that person has just now exerted more willpower than someone who has never dealt with addiction in their lives. May ever have to exert in their entire lives. That often people who seem to be struggling the most, that people are most likely to judge as having no willpower, if you actually look at what’s happening in their brains, what’s happening in their bodies, and the resources they’re spending or the courage that they have, that they are exerting tremendous willpower and so I think that that’s another …

And this is true for ourselves as well. It can help us have more self-compassion. The person who has the most anxiety or the strongest impulses, or those challenges, that is a person who actually is using the most willpower and we need to give ourselves some credit for even if the ultimate outcome today is I didn’t succeed, or I gave in, or I wasn’t able to do that thing that I said I was going to do but I got closer. Or I delayed giving in for 10 minutes.

Brett McKay: Yeah. And I think this idea of self-compassion, I think a lot of men when they think of willpower, for men at least, it’s like okay, discipline. You got to grit your teeth. You got to self-flagellate if you fail. But the research actually says that’s going to cause you to actually fail at your ultimate goal, and by exercising some self-compassion you can actually get to where you want to go. And I think a lot of … I think the problem is a lot of men when they hear compassion they think like you got to take it easy. You’re soft. Or whatever.

Kelly McGonigal: I know.

Brett McKay: It’s not like that. The way I think of it-

Kelly McGonigal: I know.

Brett McKay: … is like, I have a coach who does my barbell coaching, and when I have a bad week he doesn’t get down on me hard but he’s also not like, “Oh, you poor babies.” It’s not like that.

Kelly McGonigal: I know. I’m so glad you’re saying this. So I … part of the work that I do is research on self-compassion and compassion, and it’s very common in that field for people to describe self-compassion as self-soothing and saying things … literally yesterday I heard a psychologist say that self-compassion is when you’re able to say to yourself, “There, there, sweetheart.” I just cringed on the inside. I don’t know, that’s not what I want. That’s not my version of self-compassion. For me, it’s imagine that you believe in yourself. That you want to help yourself reach your goals, and so what would you say to yourself? What would you say to someone you believe in but you know is struggling? How would you help a friend or a loved one? Someone you care about? How would you help them step up and reach their goals to get back on track? And I think it is often like being a coach and it’s like being a mentor and it’s not always about being about this idea of treating yourself like you’re an infant who needs to be soothed.

It’s about support. And that can be firm and it can be encouraging. And that’s a form of compassion that often is what we need when it’s about reaching our own goals. I mean, feel free to say to yourself, “There, there, sweetheart”, in a moment when you’re really ill and in pain. But when it comes to willpower, sometimes the self-compassion we need is, “Hey, remember what your goal is. This is the time to show up and do it and I know you can do it. Let’s remember that last time you did something really difficult so you’ve demonstrated the strength is available to you. So let’s think about what the next step is. What would be the next positive action you can take.” That’s self-compassion.

Brett McKay: I love it. Also this idea tying in to compassion is also … one thing that can help your willpower strengthen it, is to surround yourself with individuals who will help you exercise your willpower in healthy ways.

Kelly McGonigal: Yes. So what’s so fascinating is how social our brains are, and we are constantly being influenced by other people in our environments in ways that are helpful and also sometimes harmful. And one of the best ways if you’re looking to make a change in your life is to find other people who share that goal. And we know that in that way you can sort of outsource your willpower. If you’ve got friends or you’ve got a coworker, or you’ve even got people in an online community, on social media who are with you on this, sometimes when your willpower is the weakest they kind of carry you along. They remind you what your goals are, or maybe they make decisions for you, like, okay, no, we said we were going to do this, so we’re going to do this now. That help you have willpower even when that part of you that is in deepest conflict or most exhausted and drained couldn’t find it for yourself.

And the same can be true in the other direction that if you’re trying to make a change and the people in your life are really the opposite of that, sometimes you need to make choices about changing who you spend time with, or else you need to think about giving yourself a kind of vaccine for when you’re around them if you can’t find a way to separate yourself from family members or coworkers or parts of your community. And research suggests that one of the best sort of willpower vaccines against negative influences is literally in the morning when you wake up. Just tell yourself what your biggest goal is. And that you sort of plant this in your mind so that you’re more likely to recognize when people are pulling you away from that goal.

Brett McKay: So the last thing I like to talk about which I think is interesting, some of the research you’ve highlighted about these cognitive traps that when we exercise our willpower can lead us astray is this idea of repressing. So this is I guess exercising the I won’t power but sometimes exercising I won’t power to say, “I’m not going to do this”, can actually make the thing we’re trying to avoid more tempting.

Kelly McGonigal: Yes.

Brett McKay: What’s going on there and how can we avoid that?

Kelly McGonigal: This is an interesting kind of paradox of the brain. So just imagine that you’re going to set a goal for yourself that you are not going to do something or you’re not going to think about something. So you’ve set this goal that is about not doing something, and if you are really clear about that, your brain will start to become vigilant for any threat to that goal. And so it’s going to be paying attention to the environment. Is there an opportunity to do that thing I said I wasn’t going to do? To eat it, or to buy it, or whatever it is? And you’re also going to be monitoring yourself internally for any signs that you’re thinking about it or planning it or desiring it. So you set up this kind of hypervigilance that then any time there is a trigger for it, you may be hyperresponsive to it. This doesn’t always happen.

So it’s more likely to happen when you’re really stressed or you’re really distracted, or you haven’t gotten enough sleep but there’s this paradoxical fact where you set this goal not think or say or do or consume something that because you’re then in this heightened internal state of vigilance, it just primes you to give in or it amplifies any of those impulses. And people can find themselves in this really weird trap where they’re like, “I’m going to stop thinking about this.” And the more they try to suppress it, the bigger and louder it becomes. And so there are kind of two solutions to this. One is to try to find a way to define your goals so that you’re looking for something to say yes to. So, rather than what I’m not going to do, what’s the positive alternative to it? If you are not going to complain, that’s your goal. I’m never going to complain.

I’m not going to vent. I’m not going to criticize. Well, what do you want to say? Maybe I’m going to look for an opportunity to thank someone. I’m going to look for an opportunity to call someone out for doing something positive. I’m going to look for a way to acknowledge what somebody else has contributed. I don’t know what it’s going to be. But then you set that vigilance to look for the thing you want to say yes to. And there are a lot of willpower challenges that can be redefined in this way. Not all of them. But the other thing that you can do is practice paying attention in a really open and different way to whatever the impulse or the trigger is so that it becomes a kind of strength to be aware of it without giving into it. And this is where mindfulness comes in.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well, Kelly, there’s a lot more we could talk about, but I’m curious. What would you say based on your … You’ve been doing this for 10 years and working with lots and lots of different types of people from all walks of life. What’s one or two things that listeners can start doing today to get the most bang for their buck on either strengthening their willpower, or managing their willpower in a more effective way?

Kelly McGonigal: Yeah. I think the first thing is something I’ve already said which is about strengthening your want power. And to take a moment, or take many moments and ask yourself what’s most important to you. Maybe identify the role that’s most important to you, or the goal, or the relationship, and how you want to be in that role or how you want to be in that relationship. Is there a change that you want to make? And get pretty clear about what those core goals and values are and to spend time every day reminding yourself of them. I literally don’t get out of bed in the morning if I can avoid it without doing this value goal check-in. It takes less than 60 seconds and I’ve trained myself to think of it first thing in the morning.

The second thing is if you aren’t getting enough sleep to try to get a little bit more sleep. There’s no fixed number, but we know that the way that sleep deprivation affects the brain, it basically derails all of the neurological processes that make it easier to have willpower and to use your willpower. So that’s a lifestyle change. If you’re going to make one, sleep would be probably the number one. And the third thing I would say is if you know what your goal is, there’s something you’re trying to change or there’s a goal that you’re pursuing, to get very clear about something you can do today that is consistent with that, and to celebrate it. It’s the small thing. It’s the one action.

An example I sometimes give people, well how would that apply to something like quitting smoking? And there’s research that if you can delay the first cigarette of the day by a few minutes that that can lead to an upward spiral that increases your chance of quitting in the long-term. And that’s something that anyone could do today or tomorrow. Just delay it a few minutes. And figure out what that is for your goal. What’s the one thing that you absolutely can do today that is consistent with your goal even if you don’t have any idea yet how something that small could lead to the final success that you’re dreaming of. And trust that often with change and with willpower, this is incremental. It’s not all or nothing, black and white.

Brett McKay: Baby steps.

Kelly McGonigal: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah.

Brett McKay: What About Bob. You heard of that movie?

Kelly McGonigal: Yes. I do.

Brett McKay: Well, Kelly. Where can people go to learn more about your work?

Kelly McGonigal: My website. Kellymcgonigal.com.

Brett McKay: And you got a new book coming out pretty soon, correct?

Kelly McGonigal: I do. It’s called The Joy of Movement. What I try to do is find the best research that people aren’t talking about that can improve people’s lives. So I did a book on willpower, a book on stress, and this next book is really about how to find mental health and happiness and community through the body and through physical action.

Brett McKay: I love that. That’s right up my alley. I think we’re going to have you back on the show to talk about that too.

Kelly McGonigal: Great.

Brett McKay: All right. Kelly McGonigal, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Kelly McGonigal: Likewise.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Kelly McGonigal. She’s the author of the book, The Willpower Instinct. It’s available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find out more information about her work at her website, kellymcgonigal.com. Also check out our show notes at aom.is/willpower, where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well that wraps up another addition of the AOM Podcast. Check out our website at artofmanliness.com where you can find our podcast archives. There’s over 500 episodes there, as well as thousands of articles we’ve written over the years about things like willpower, for example. And if you like to enjoy ad-free episodes of the Art of Manliness Podcast, you can do so only on Stitcher Premium. Go to stitcherpremium.com. Use code Manliness at checkout to get a month free of Stitcher Premium. After you sign up, download the Stitcher app on Android or iOS and you can start enjoying ad-free episodes of The Art of Manliness Podcast. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. It helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you think would get something out of it.

As always, thank you for continued support and until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding you not only to listen to the AOM Podcast but put what you’ve heard into action.