It’s not uncommon for former law enforcement officers and intelligence agents to write self-help books where they share how the lessons they learned in their professional careers can apply to people in any walk of life.

What is rare is for one of these officers-turned-authors to publicly prove they know what they’re talking about and that their tips work, as Derrick Levasseur did by winning the reality show Big Brother.

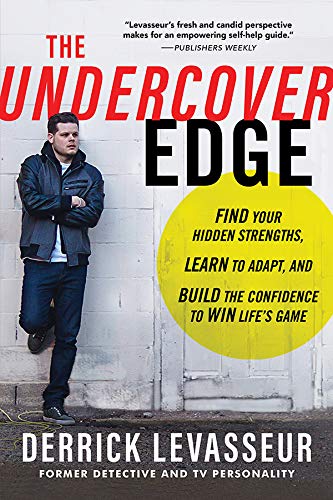

Derrick is a former undercover detective, current private investigator, and the author of The Undercover Edge: Find Your Hidden Strengths, Learn to Adapt, and Build the Confidence to Win Life’s Game. Today on the show, Derrick shares how he became an undercover police officer, what he learned from that job, how he applied those lessons on Big Brother, and how you can use similar techniques to influence others, know when someone is lying, and bounce back from adversity.

Resources Related to the Podcast

- Derrick’s season of Big Brother

- Derrick’s podcasts

- The Johari Window

- AoM Podcast #830: How to Read Minds and Detect Deception

Connect With Derrick Levasseur

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. It’s not uncommon for former law enforcement officers and intelligence agents to write self-help books where they share how the lessons they learned in their professional careers can apply to people in any walk of life. What is rare is for one of these officers turned authors to publicly prove they know what they’re talking about and that their tips work, as Derrick Levasseur did by winning the reality show Big Brother. Derrick is a former undercover detective, current private investigator, and the author of The Undercover Edge. Find your hidden strengths, learn to adapt, and build the confidence to win life’s game.

Today on the show, Derrick shares how he became an undercover police officer, what he learned from that job, how he applied those lessons on Big Brother, and how you can use similar techniques to influence others, know when someone’s lying, and bounce back from adversity. After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/undercover.

All right, Derrick Levasseur welcome to the show.

Derrick Levasseur: Thanks for having me, Brett.

Brett McKay: So you’ve had a really interesting career, and I wanna talk about this ’cause you wrote a book about it and you provide some lessons to just regular people from your career. You started working for the police at a really young age. I was surprised how young you were when you started.

Derrick Levasseur: Yeah. Me too.

Brett McKay: How old were you when you signed up and what nudged you towards a career in law enforcement?

Derrick Levasseur: I was 20 years old, so not even old enough to buy my own bullets. I actually had to have the police department provide my ammunition at that point. So that was an interesting way to start my career. The guys that were older than me on the job really loved that. I have to say, when it came to nudging me into law enforcement, I didn’t necessarily have any ambitions to be a cop before the year leading up to that whole chain of events where I was in college, I was going for a two-year degree, I was playing baseball, I was getting ready to transfer to a four-year school, and the summer between my sophomore and junior year, I had just finished my criminal justice degree, my associate’s degree.

The chief of police for the police department I ended up working for was a longtime friend of mine. I grew up in the city where I eventually worked and he knew me, and I had a pretty troubled childhood in some ways. My parents were good, but I got into a lot of fights, and the chief was someone who as a patrolman always looked out for me, was a role model, was someone I looked up to. And so over that summer, when I was getting ready to go into my junior year, his name is Joe Moran. He said, hey, why don’t you apply for the police department? Give it a shot just to get your feet wet and see what it’s like. And when you’re done with your bachelor’s degree, maybe you come back. I don’t think you’re gonna get hired this time around, but it would be great for the experience.

So I ended up taking the test, and it was about 300 or 400 people there. And to make a long story short, about three, four months after going through all the testing, the physical, the mental, the psychological, he calls me up and says, hey, I need you to come to the police station. So I go to the police station and I’m expecting him just to tell me like, hey, here’s where you did well. Here’s where you didn’t do well. This is what you should work on in the future. And he goes, you know, come on in. Sit down.

And he says, listen, I’m in a really interesting predicament right now ’cause I had no intention on hiring you, and yet you finished first overall out of everyone. So I also cannot not hire you ’cause what’s my reasoning for not hiring you other than you’re young? So at this point, if you feel that you’re ready, I’d like to offer you the position. And at that time, I was 20 years old, broke, really not going anywhere in my baseball career. I was okay, but I wasn’t gonna play professional. And I loved the idea of giving back to my community. So I decided to take that leap and it was one of the best decisions I ever made.

Brett McKay: So you started working for the department, then you started doing undercover work. How did that happen?

Derrick Levasseur: Well, again, Joe Moran is gonna be a common theme in my law enforcement career story. It’s my 21st birthday. Now, a little backtrack. When you go to the police academy, you’re there in Rhode Island with police officers from all other agencies. Everyone goes to the one police academy. So word got back to these other police departments that there was this really young kid who was in their academy with them. And not only was I young, but I looked even younger. And so I get this call on my 21st birthday, I had a couple celebratory drinks the night before. I get a call from Joe Moran in my hotel room, and he says, listen, there’s something going down at a local university. They believe there might be some drugs, maybe some date rape drugs being distributed throughout the school. I got a call from a certain police department. They heard about you. They’d like you to pose as a student and see what you can find. Obviously, that’s the dream, right? Like when you grow up, when you’re thinking about being a cop at all, you’re not thinking about the patrolmen who are writing tickets. You’re thinking about bad boys. You’re thinking about Will Smith and Martin Lawrence, right? So when he says that to me, that’s like music to my ears.

I basically ditch all my friends and go right into the police department, end up doing the undercover operation, and it was extremely successful. We ended up arresting 11 people, identifying even more individuals than they initially thought. And I caught the bug. I had the itch, and I knew right then and there, that’s where I wanted to go with my career. Now, as a patrolman still at that point, you can’t just jump into detective work. But what happened with me was as I was learning how to be a patrolman, I was also working for different agencies in a short-term capacity as an undercover detective. So as my career progressed, and I reached a point where I was eligible to be in the narcotics division full-time, it was a clear transition that I was gonna be the next up for that spot, which happened. I did another four or five years as a narcotics detective, and then two years as a sergeant of narcotics. And it was probably the best part of my career.

Brett McKay: Yeah. So it sounded like you had the 21 Jump Street transition to undercover work. You infiltrated younger people.

Derrick Levasseur: Yep. That was my niche. And everyone has a niche, right? Depending on what the job dictates or what the case involves, you need a different undercover officer. And for me, that’s the role that I played. And there wasn’t a lot of people on the job that fit that role. They either looked too much like a cop, or they acted too much like a cop. And they couldn’t infiltrate those certain areas. So I was in high demand when I first started. That was for sure.

Brett McKay: Then you ended up as a contestant in winning Big Brother. How did that happen?

Derrick Levasseur: So I was 30 years old. And when I was on my deeper portion of my undercover career, when I was really under there and I was doing a lot, I couldn’t really go out a lot. And so I would be at home, and I’d be at home with my wife, and I was looking for stuff to watch. And I ended up stumbling upon this show called Big Brother. And I really got into it. And part of the reason I really got into it is ’cause I think a lot of us find shows that we think we would be good at, so we like to watch and critique the people that are playing it. And I remember multiple occasions where I would say to my wife, oh man, if I wasn’t a police officer, I would absolutely kill this show. I’d do so well. And everyone’s like, yeah, sure, buddy. Sure you would.

So when I got out of narcotics work and I was a sergeant, it was my 30th birthday, and it was a bucket list. So I basically just sent in a video. I didn’t even send in the proper amount of time, but it was just to say I did it. And I started my video by saying, you know, I was an undercover detective, I have a business degree, and if you put me on the show, I’m gonna win. And within like two weeks, I got a call back. And the Big Brother people said, oh, you think it’s that easy, huh? You think you’re gonna come on the show? We’re just gonna come out here, you’re gonna control everything? And I said, no, I’m probably gonna lose right away. And they said, but you said in your audition tape that you’re gonna win. I said, no, I said what I needed to say to get you to call me. Here you are. And they said, oh, okay, yeah, you need to come to New York. And then the process went from there.

So it wasn’t what I planned to happen, but it worked out. It really did. And it was a great experience. Big Brother was an awesome experience. When you win the money, it’s hard not to enjoy what’s happening.

Brett McKay: Did you use your experience as an undercover officer to help you win Big Brother?

Derrick Levasseur: Absolutely. So for anybody who doesn’t know, Big Brother is basically 16 people in a house for 100 days. And each week someone goes home. And during that time, you have to develop alliances and build relationships. And I went into the house and told them that I was a Parks and Recreation coordinator. Didn’t even tell them I was an undercover cop. And I used my ability to read people and communicate with people and find commonalities with individuals that you may not necessarily get along with to build relationships that were bigger than just our alliances. They became actual friendships. Some of those friendships I have till this day. And it wasn’t until after the votes were locked in that I revealed to the entire cast that I was an undercover detective. And it was a great TV moment.

Brett McKay: That’s awesome. So what have you been doing since then?

Derrick Levasseur: So after Big Brother, I went right back to being a police officer. I had no ambitions to be on TV. I won the show. I got what I wanted out of it. I went back to work. But I had an agent reach out to me. You have a bunch of people reach out to you afterwards and they all have these big plans for you. And I wasn’t buying any of it. But I had one agent, Harry Gold, who’s still my agent to this day, reach out and say, hey, you should be back on TV. And I said, no, I’m not interested in any of these shows. I did my one show. I’m done.

And he said, what about True Crime? I said, what’s True Crime? He said, listen, just come out to LA, let me grab you here. So I go out to LA and he tells me about this project involving OJ Simpson where there’s a private investigator who believes he’s innocent and he can prove it. So they hired me for the show for Discovery. It was a six part series. And I said, screw it, let’s try it. Did the show. It did extremely well. And they decided to give me my own show, Breaking Homicide. At that point, I had about three years back on the job since Big Brother and it became a little difficult to do both. I was traveling all over the world.

I had gotten my private investigator’s license at that point so I could work nationally, not just in my own jurisdiction. And I had to make the decision as to whether or not I was gonna stay a cop or I was gonna pursue this career as a private investigator/analyst, TV host, whatever you wanna call it. So since then, I’ve left the job. I left the job in 2017 after 13 years. I opened my own private investigator firm that year, which is still in business. We’ve been in business for about seven, eight years now.

We do genetic genealogy. We do cold case investigations. We do a lot of civil cases, surplus searches, error searches, you name it. I have a studio called Square Mile Studios, which is an homage to my hometown, Central Falls, Rhode Island, where we currently have two shows. We have Crime Weekly, which is on YouTube and on audio podcast platforms. I have another show called Detective Perspective, which is also on YouTube and on audio and that focuses on unsolved cases. And we got some other shows in the mix. In addition to that, I do some TV stuff. I have a show called Crime Feed with Nancy Grace. I’ve done some talking head stuff for different networks. It’s all in the same ecosystem. It’s all under the True Crime theme.

It’s what I enjoy. It’s my passion and I’ve found ways to use that passion in different platforms in different ways. And I will tell you this, to bring it back to Big Brother, everyone has a lot of big decisions they make in their life. No decision had more of an impact on my life than Big Brother ’cause I can tell you right now, if not for Big Brother, none of these other things that I’m talking about right now happen. So it’s a crazy life. I’m 40 years old and even sitting here talking to you about it, it’s surreal for me even to this day. I feel like I have this constant case of imposter syndrome.

Brett McKay: So you wrote a book a while back ago called The Undercover Edge, where you take readers through the lessons you’ve learned as an undercover police officer that are applicable to any person’s life. If you take a step back and look at the big picture, why do you think undercover work provides so many lessons about life in general?

Derrick Levasseur: Well, Big Brother was the proof of concept, right? ‘Cause I didn’t tell them I was an undercover detective. I just used a lot of what I learned while working undercover in this social experiment to prove that the same things that you do in undercover work can be applied anywhere. And it’s really it’s not that complex. It’s simple interpersonal skills. It’s understanding not only yourself, but the person you’re communicating with. I referred to it in the chapter as know your target.

Understanding not what motivates only you, but what motivates them. So you can phrase your questions and your suggestions in a way that’s that incentivizes them to wanna do it, not just for you, but for themselves. And when you’re trying to build relationships, whether it’s in your personal life or whether it’s in your professional life, you wanna try to build a relationship that’s based on genuine commonalities, things that you can actually both agree on so that as you’re growing together in that relationship, it’s not disingenuous. There’s something really there that you can latch on to and utilize to build a stronger connection. And that’s really what I did in Big Brother and what I’ve done not only in undercover work, but in my personal life to build relationships with the people that are personal to me, but also my employees, the people that work for me and having individual relationships with them and understanding it’s not a one size fits all. Every person that works for me, they respond to different things. My job is to understand what that is and that way I get the most out of them.

Brett McKay: Yeah. That was a big takeaway for me is that the thing from your undercover work, undercover work is all about social relationships. And in order to succeed there, you have to develop those social skills. And that’s the same thing in life in general.

Derrick Levasseur: Of course.

Brett McKay: Whether it’s work, family, et cetera. Yeah. It all comes down to social.

Derrick Levasseur: It’s not brain surgery, right? Like at the end of the day, you can be an intelligent person and still be horrible socially and you’re gonna have trouble. But if you can talk, even if it’s in a romantic relationship, we always hear the jokes like he’s not the best looking guy, but man, he can talk, right? That’s really what it’s about. It’s about being a good communicator and understanding who you are as a person, your strengths, your weaknesses, acknowledging both, and then utilizing what you have at your disposal to benefit you in whatever you’re trying to accomplish, whether that’s just getting to know someone better, building a stronger friendship, or in a professional setting, getting an employee to be motivated by the work you’re asking them to complete.

Brett McKay: So going on that line of knowing your strengths and weaknesses, this is something you talk about in the book I thought was really interesting. The Johari window.

Derrick Levasseur: Yeah, Johari. Johari window.

Brett McKay: Johari window. Okay.

Derrick Levasseur: That’s how it’s pronounced. It could be Johari too. I’ve heard people pronounce it both ways.

Brett McKay: All right. Johari window. What is that Johari window?

Derrick Levasseur: So you’re pulling back from memory here, but I believe it was made by two individuals. I think their first names were Joseph. I apologize. I don’t remember their last names. I believe it was Joseph and Harrington, and they combined the two to create this Johari window. And it’s self-explanatory. If you look it up, it’s heard in the audio podcast, but it’s basically four separate windows into yourself, right? Or quadrants, whatever you wanna refer to it as. And what it actually, to me, represents is just a visual representation of you.

It’s a self-assessment. And we could talk about the Johari window for probably 30 minutes, but the short version is you break it down into different quadrants. One being what’s known to you, what’s known to others, what’s known to them, but not necessarily known to you. Like maybe flaws you have that you don’t even realize you have. And then what’s known to yourself, but not known to others. Things that you are passionate about that maybe you haven’t shared openly with people or maybe struggles that you have that people are unaware of.

And then the final quadrant would be things that are yet to be discovered by anyone, not only yourself, but the people around you. And for me, taking stock and creating an audit of where you are allows you to better understand who you are and where you need to improve and where you need to capitalize on things that you’re already good at. And I think it’s sometimes difficult, specifically the quadrant of things that are known to others, but not necessarily known to you. The question would be like, well, how do you write those things down if they’re not known to you yet? There are times in our life where people may give you hints to those flaws or areas that you need improvement on, but you refuse to listen or it’s something that you just don’t wanna believe.

And they also refer to this, which isn’t the most politically correct term these days, but the blind spot, right? Where there are things that you need to improve on, but you don’t necessarily want to. And when you visually write it down, if you can take that acknowledgement and write it into that box, you can actively work towards moving it from the not knowing it about yourself or not acknowledging it about yourself to the box where you do accept what it is. You understand its limitations and you can work on turning that into an asset. So again, Johari window, it’s not gonna change your life, but I think it is important sometimes to take stock in who you are as a person and have a visual representation of where you are now and where you wanna be. And Johari window is just one of those many tools that can help you do that.

Brett McKay: Yeah. And when you were an undercover cop, did you use the Johari window on the fly for every situation? Like, okay, what are my strengths for this situation? What are my weaknesses for the situation?

Derrick Levasseur: Of course. I don’t think I necessarily referred to it as the Johari window back then. It was something that I had learned about in college and then forgot about and came back to after getting my business degree where you start to be more of like, I guess a scholar, if you will, where you start to try to find applications and studies that will help assist you in better ways in your personal professional life. But for me, it was just knowing my target, right? I would get some counterintelligence on the person or the group that I was trying to infiltrate. I would see what they liked, what they disliked, what they were gravitated towards, what they pushed away. And I would look for genuine things within myself that would allow us to create authentic connection.

Even with these criminals, there were things that we had in common and those are the things that I would try to focus on as opposed to being disingenuous and trying to find areas that I thought they wanted to hear about, even though they weren’t true to who I was. It may be sports, it may be politics, it may be just the way we conduct ourselves in public settings. But I would try to find things that even though this person was doing something that I didn’t necessarily agree with, I could still find areas that we were the same. And those were the areas I would focus on. It would also allow me to be a better undercover cop ’cause when they questioned me on those things, I just had to be myself. So there wasn’t really an opportunity to trip me up ’cause I stuck with what I knew and who I really was.

Brett McKay: I thought that was interesting talking about the target and developing a dossier about the target. The amount of pre-work that was involved, I think sometimes people think, oh, this guy went undercover. You just, okay, here’s the assignment, now you go undercover. There’s actually months, maybe years potentially, of pre-work before that happens. Walk us through, what sorts of things were you trying to figure out before you actually infiltrated a group?

Derrick Levasseur: It depends on the case. In some instances, it can be exactly what you described where there’s case agents who are working on a case with a particular organization for six months to a year and then when the undercover comes in, like myself, we’re given a case file on that person to catch us up to speed and I may have a couple weeks to a month to review it and ask questions and critique it and make it more in line with what I can do. Then there are other times where you may have a couple hours and they’ll give you a case file and say, hey, this is exigent circumstances. We need to get this going now. Here’s the person. Here’s where they are. Here’s what they do. Here’s what we have on them. Here’s where they frequent. Here’s the type of friends they hang out with. Gather as much intel as you can and develop a personality as quick as possible.

So yeah, the more time, the better. The more you can understand your target, the better off you’re gonna be at getting whatever you want out of them or building some type of relationship as quickly as possible. But it does vary. Sometimes you have more time. Sometimes you have less. And that adaptability is what separates, I think, the good detectives from the bad ones where the people who can adapt not only prior to the investigation, but also on the fly in that moment, they’re gonna be the most successful.

Brett McKay: How did you use this idea of developing a profile for a target? How did you use this on Big Brother?

Derrick Levasseur: Same thing, right? When I went in there, it’s by being a good listener. I describe another chapter in the book where it’s so you have the right to remain silent and listen. It’s important to listen. It’s important to just shut up and listen to what the person is genuinely saying, even what they’re not saying, and to understand what motivates them. ’cause if you’re actually listening to them and not just thinking about what you’re gonna say next, you’re gonna learn a lot of information. And from that information, you can develop your approach to how you’re gonna communicate with them in a way that’s more effective. So in Big Brother, I went in there and I just wanted to be someone they could talk to. I wanted to be their brother, their father, their uncle, just a friend.

Whatever they were looking for, I wanted to be that person. And we would talk about their friends, their family members, their dreams, their aspirations, their motives for being in Big Brother. And once I learned what those motives were, I could frame my questioning or my instructions in a way that would incentivize them to do it. So for example, just one example, you had people who weren’t there to win the money. They were there to gain notoriety or maybe get exposure for their singing career or whatever. So when I went to certain people, I may be wanting the same thing, but the way I frame it to one person may not be that way to another. So for one person, I may say, man, you make this move. If you put this person on the block, I can tell you it’s gonna be a TV moment. You’re gonna get so many followers from this.

People are gonna be crushing your phone after this to get you to come on and do other shows with them ’cause that’s gonna be a memorable moment. And for that person, that’s all they needed to hear. For someone else, it may be financially motivated, where it’s like, listen, if you do this, there’s an opportunity that you could get further in the game, which is gonna allow you to generate more income ’cause the longer you’re here, the more money you make. So if you want to increase your longevity in this game, it’s important to get this person out now. Now, the real secret sauce in all that is I was having them do things that were ultimately beneficial to my game. They just didn’t see it that way ’cause I framed it in a way that it appeared on the surface to be good for them. But in reality, this was a bigger plan that I had for myself to get to the end.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I thought that was an interesting takeaway. It was a big takeaway for me after reading your book is when you’re developing a profile on somebody, whether it’s, I mean, it sounds mercenary to talk about people as targets outside of a criminal situation, but you do do that. Like it could be a potential employer. It could be an investor. It could be a potential romantic partner. You’ve got to develop some sort of profile them so you can figure out how you can connect with them.

Derrick Levasseur: Right.

Brett McKay: But the idea of finding out what someone’s motivation is, that’s often like the last tumbler and the pin in that tumbler lock. If you can click that, then like you can really figure out how you can influence this person.

Derrick Levasseur: 1000%. Yeah. It’s and also how they receive praise, right? Like how you perceive praise, how I perceive praise. It could be different depending on if it’s a personal situation or professional situation. Just in a personal situation, if it’s your significant other, I may be more prone to just wanting physical touch where my wife may be more receptive to physical gifts, you know? So I don’t wanna go to her and start hugging up all on her and doing all these different things with that’s not really what she’s looking for. There may be other ways to get through to her that incentivizes her to continue whatever I’m wanting her to continue, whatever behavior or action she’s carried out that I like. And so I think it’s understanding, again, back to this Johari window, understanding yourself, but more importantly, understanding the people around you and what makes them tick.

Brett McKay: We’re gonna take a quick break for a word from our sponsors. And now back to the show. How do you figure out someone’s real motivation? ’cause here’s the thing. Sometimes people say publicly like, this is why I’m here, but really it’s not. So how do you figure out that hidden motivation?

Derrick Levasseur: So it can be difficult. And I do think that there is just an innate ability to it as well, just like a lot of things in life. I grew up in a very diverse community and it was dangerous at points and my safety was based on my ability to interpret people’s true agendas relatively quickly, which ultimately led to a successful law enforcement career. But there are things you can learn. And I do think the more you let people talk and the more you listen, the more likely they are to either expose themselves or contradict themselves in a way where you can make note of it and understand what their true agenda is, even though they may be saying one thing, but their actions suggest another. And that also comes down to verbal and nonverbal cues. We didn’t even talk about that, right? The verbal cues are what they’re saying, but they could be saying something, but yet their physical actions show another. So you have to not only be a good listener, but you have to be a good observer.

So in the Big Brother house, again, this is applicable to life as well. Someone could be talking to you about something and saying, Hey, I really like this person. And yet you can see what they’re doing physically suggest another thing. So you have to be aware of both. You have to make an assessment of it. You have to note and document maybe physically or just in your head what you’re seeing and how it lines up with what they’re saying and come to an educated decision on what you think their true intentions are. Are you always gonna get it right? No, absolutely not. And you’ll have to make adjustments when that happens. But that ability to at least make an initial assessment and adapt on the fly is critical to the success that you’ll have.

Brett McKay: I thought it was an interesting part of your book talking about reading body language.

Derrick Levasseur: Oh, yeah.

Brett McKay: We’ve had people on the podcast before, like body language experts, to talk about body language.

Derrick Levasseur: And they’re way more nuanced than I am, for sure.

Brett McKay: Yeah. But a common response to reading body language like, well, it’s just bunk, like you can’t do that. But it sounds like, no, it’s not. You actually use this not only as an undercover cop, but you used it on Big Brother.

Derrick Levasseur: Yeah. There’s people who make a living doing this. And they’re a lot better than me, obviously. There’s people like, I think about the podcast, the behavior panel. They’re incredible at this. Like, there’s studies that show that there are subconscious behaviors that we do when we’re feeling a certain way, feeling a certain emotion that we’re not even aware of that we’re doing. And what I would say to just put it in perspective, it’s not a science in the sense of everyone does the same thing. Like, oh, if you’re lying, you’re always gonna look down to the right. That’s not everyone. What I would say is every person is different. And the number one thing you could do goes back to being a good observer and being a good listener. You have to sit there with this person, sometimes for hours, sometimes for days. And you have to develop a baseline for them. What I mean by that is everybody’s different. Things that may be indications of deception in certain cases may be just a normal behavior for them.

So your job initially is to be a good report taker and document what you see, both verbally and non-verbally, so that you have an understanding of who they are and what they normally do. That’s when you can transition the conversation to what you really wanna know about. Whether it’s in an interrogation or just at the job, you can start to ask them questions that may elicit a specific emotion. Maybe it’s something that’s gonna make the situation a little bit more tense. Maybe make them a little bit more anxious. And that’s when you wanna compare the behaviors that you saw under normal circumstances when there wasn’t really anything on the line to what you’re observing now.

Are there any differences? Once you document those differences, you go back to normal questions, maybe about sports, maybe about the weather, to see if they continue to display those new behaviors you just observed. If they don’t, it could be an indication of some type of anxiety or deception, or it could just be an outlier. It’s on you to document those things to see if you can connect the dots and also recreate a situation where they display that behavior again. And if you find that they’re only doing it with certain questions, now you have an indicator that is specific to them. So when people say it’s bunk, I think that’s more in line with people who say, hey, you can read this one book and you can tell when every single person is lying just by reading this book. I don’t believe in that, but I do believe there is truth in the idea that we all have certain traits about us, subconscious behaviors that we don’t even know we display. And if someone’s sitting in front of you long enough, they can identify those elements and use them to better understand you.

Brett McKay: Okay. So just to recap, that’s a cool interrogation technique. So if you suspect someone might be lying about something, the thing you can do is you start off talking to them. You just talk about innocuous thing. You ask them questions that they would.

Derrick Levasseur: Talk about baseball.

Brett McKay: Baseball, movies, whatever.

Derrick Levasseur: Yep. Yep. They’re relaxed. They’re not bladed. Their hands aren’t crossed. They’re not rubbing their fingers. They’re not rubbing their knees. Yep. Exactly.

Brett McKay: So that’s establishing the baseline.

Derrick Levasseur: That’s your baseline.

Brett McKay: This is… There’s no anxiety here. No stress.

Derrick Levasseur: That’s right.

Brett McKay: And then you throw in a question like, well, tell me about what was going on when you were at this time. And then…

Derrick Levasseur: Yeah. Did Joey take that cash off the counter? Did you know who took that cash off the counter that was there the other day?

Brett McKay: Yeah. And then they start getting a little cagey. It’s like, okay, something’s going on here. Then you go back to talking about the Mets again.

Derrick Levasseur: Yep. And then if they continue to display that behavior, it may just be an outlier. It may just be a red herring. Or if they go back to being relaxed, not bladed, not wringing their hands, not rubbing their thighs, not tapping their feet. Now it’s something where you go, hmm, okay. And I’ll see back and forth. I’ll go back. I’ll blade back into that uncomfortable conversation to see if they start displaying that behavior again. Now that doesn’t automatically mean they’re guilty of something, but it does indicate a level of anxiety that they’re not displaying when you’re asking normal questions. Again, not a direct science. It’s not applicable to everyone. But I think most people would hear what I just said and say, yeah, that makes sense.

Brett McKay: Did you use on Big Brother? So like you talk to somebody.

Derrick Levasseur: Of course.

Brett McKay: Like, oh, we’re just talking about our family. And then you’d be like, so are you gonna vote off so and so?

Derrick Levasseur: Every day. Every day, every hour. It’s a big reason I was so successful is not only understanding who they are, but then also understanding some of their nonverbal cues that would indicate they were lying to me or they were anxious about what I was referring to or what I was questioning them about, which would allow me to say, you know what, maybe I shouldn’t trust this person. They got to go home.

Brett McKay: Another tactic you used as a police officer when you’re trying to figure out what happened in a situation, separating people, why is separating people a useful tactic to get to the truth?

Derrick Levasseur: Well, you think about it when people have the chance to collaborate and get on the same page, it’s very easy to come up with a story and stick to it. But when you separate them and there’s a wall between them, there may be some distrust there. And at the end of the day, they don’t know what someone’s saying on the other side of that wall. So by separating them, you can not only get true stories from each individual party, but in an interrogation situation, you can also use it against them. And some of your listeners may not be okay with that, but that’s an acceptable tactic in law enforcement where if you and I are being interrogated and they come into me and they know that I’m lying and they know more of the story than they’re letting on being the investigators and they say, well, you’re telling me this, but Brett’s telling me that. Brett may not have said anything, but I don’t know that.

And if there’s some concern that I have about Brett ’cause of my trust or lack thereof for him, I may start divulging information to save my own ass. And in reality, Brett hasn’t said anything. So it is something that can be done. It’s also referred to as trickery. Like I said, not everyone loves it, but criminals usually have the one up on everything ’cause they know what happened and we don’t. So anytime we can separate parties and use whatever tactical advantage we are legally allowed to use, we will do it. And that is one of those that can be very successful because again, we don’t allow them to communicate with each other, which can embolden them to lock up and not say anything. When you separate them, it creates a level of anxiety where they’re saying to themselves, I wanna get the deal before him ’cause if I don’t, he could be testifying against me.

Brett McKay: Yeah. You’re creating the prisoner’s dilemma.

Derrick Levasseur: Yeah.

Brett McKay: That’s it yeah.

Derrick Levasseur: Yeah. Exactly. Exactly.

Brett McKay: And I can see like a parent using this. Like the lamp is broken.

Derrick Levasseur: Of course.

Brett McKay: The lamp is broken. And there’s two suspects.

Derrick Levasseur: Yep.

Brett McKay: Instead of talking to them both right there, it’s like, all right, child number one, come here. I’m gonna talk, get their story. Child number two. And there’s probably gonna be some conflict there and then you can start figuring things out.

Derrick Levasseur: Of course. And that’s such a basic way, but it’s so true. And it can apply to even more severe situations where whether it’s employees or employers or a romantic partner, when you can separate the parties and they’re not allowed to bounce off of each other’s behavior and verbal intonations, whatever they’re saying, it gives you the one-up, which anytime you can get that advantage, you need to do it.

Brett McKay: So going back to this idea of just listening, just shutting up and listening, you talk about another tactic you use as an officer and you use this on Big Brother too, is just continuing the pause, like allow for an awkward pause. Why is that such a useful tactic to get more information from people?

Derrick Levasseur: It’s so funny ’cause that’s not something anyone ever taught me. It was just something that I realized. There is this psychological expectation where when you talk to someone, you might say a statement or two and you’re looking for some type of acknowledgement, whether that’s physical or verbal. And in most instances, it doesn’t apply to everyone, what I found was that when someone I was interrogating was telling me a story, they would give me just enough where they felt like I would be satisfied. And they’re looking for that response, that rebuttal, that dialogue, so that there’s not this awkward moment of silence. Somebody has to fill that air, right?

So when they start talking, they may say something and they may say, initially, hey, I don’t know much, but I do know that there was a red car there, there was definitely a red car there. And I look at them and I go, I’m not gonna say anything else. It does come off as awkward, I promise you. It’s like a 10, 15 second gap, but then they go, and this doesn’t happen every time. This isn’t like, people listening may say, oh yeah, I’m sure that’s gonna work, but it’s another tool you can try. If it doesn’t work, you go on to the next tool. But in certain cases, they may go, the first three digits of the license plate were RTX, but honestly, that’s truly all I know. And I may give them a look like, really? Come on.

Again, not saying anything, there’s just this awkward pause. And in some cases, they’ll go, what do you wanna know? What’s gonna get me out of here? And I’ll go, you tell me. I know you know more. You tell me. I’m not saying much of anything. I maybe said five words in this whole interaction. The person was this white dude with a white beanie on, but really, genuinely, that’s all I got. You can arrest me, I don’t care, that’s all I got. But just by the momentary pause, I’ve gained little bits of information, little pieces of the puzzle that can help solve the overall case. Now, would I say this works a lot in my personal life? No, ’cause those people know you. And if you’re just sitting there looking into their eyes, they’re looking at you like you’re a weirdo. This is more for an interrogation.

I wouldn’t necessarily suggest that people do this in their personal life, but it can apply, I think, with your kids, I think with certain employees, when you’re investigating either a misconduct or a theft, and you’re in that position of authority, you have the ability to keep that pause or maybe pretend like you’re writing something down where it creates this psychological need to fill that silence. And if you’re not filling it, in some cases, the other person will.

Brett McKay: Okay. I like that. It’s interesting. So in your career as an officer, you had to do something that very few officers do. I think it’s like 27% of officers actually have to fire their gun outside of a range. So you had to shoot someone in self-defense and that person died from their wounds. How did you respond to that?

Derrick Levasseur: Not well at first. It was a very difficult situation to go through. I was 23 years old. I don’t think I can talk about this without giving a little backstory for everybody going, oh my God, that conversation just took a turn.

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Derrick Levasseur: But it was a 911 hang up. And for anybody who doesn’t know, 911 hang ups are very common in law enforcement. They happen almost every day. And so it was Easter Sunday. Multiple officers were at the station. Again, it’s Easter. It’s a slow night. So we thought. And so we responded to this house ’cause it was a 911 call. The phone picked up and then just hung up. So we get there and we get up to the second floor and there’s a person standing there. They only speak Spanish. So a Spanish speaking officer that was with me starts talking to them. We learned that there was a fight on the third floor. Get up to the third floor, there’s another individual standing there and he’s standing in the hallway.

And it’s hard to describe this over an audio podcast, but he’s standing on this landing with his shoulder, his left shoulder facing this apartment door that’s currently closed. So I’m the first one going up the stairs. I start to talk to him. I realize again, he’s Spanish speaking. So I continue to walk up to him and then past him where now I’m also standing on the landing to his right facing the door to his left. And the officers, there’s three other officers. One of them is on the stairs speaking Spanish to this person. And all of a sudden, I don’t understand what they’re saying, but this individual opens the door to the apartment. When he does, it’s just this completely dark apartment.

I can see it’s a pretty big apartment. I can see multiple doors lining the hallway that I can see down. And one of the doors, I can tell that it’s open ’cause there’s a light emitting from the room. I can’t see in the room, but I can see the doorframe and that it’s lit up. Well, as they’re sitting there having this conversation, a figure comes out of the room. I can see the silhouette and luckily I could see it pretty well. I couldn’t see them, but for some reason I could tell that when they walked out of the room, they were looking right at me. They were looking right through my soul.

And fortunately enough for me, as I scanned their silhouette from their head down to their feet, I could see one thing that stood out to me immediately. And that was the fact that they were holding a long knife by their side. And we always learned at the academy that when you see a knife, the first thing you should do is yell knife as loud as you can. And it sounded so stupid in the academy, but creating that muscle memory over the years, it was the first thing I did.

I immediately yelled knife. And as I yelled knife, the silhouette turned towards me and started running towards the door. So I pushed the individual that had been standing on the landing with us down the stairs. And at this point, the other officers are going, what the F is going on? ’cause they can’t see any of this. But I pull out my gun. I back up into the window that’s behind me on this third floor landing. And I could feel the cold air on my back. I almost fell out the window. I have my gun out and this individual comes all the way up to the door. He gets in the doorway. He’s got the knife over his head. I can see his eyes are bloodshot. He’s breathing heavy. And I could tell that he’s under some type of substance.

And we were only about a foot away from each other, but I didn’t shoot him ’cause right when I was about to, he stopped. And I really didn’t wanna do it. I didn’t wanna shoot him. So he ends up shutting the door. And at that point, we have to go inside ’cause he could be in there hurting himself or hurting someone else. And at that point, we had developed the information that there was a fight between multiple people. And we hadn’t found those other people yet. For all I know, they could be in that bedroom with him and he could be killing them. So we have to go in. So I kicked the door in. All four officers, including myself, go into the apartment. We’re in the kitchen with him.

He’s standing there with a knife over his head. Two of the officers with us speak Spanish. They’re telling him in English and in Spanish to drop the knife, drop the knife. He’s not doing it. And we know this isn’t gonna end well. So we gave him enough room to move around. We didn’t want him to feel cornered. And we really just wanted this situation to deescalate and for it to end. But unfortunately, that didn’t happen. And he ran to his right, back down that hallway that I was describing earlier, but into the furthest room, which was the living room. So we stack up again, the officers, ’cause it’s a very narrow hallway. And I end up being the first one.

And as we’re going down that hallway into that room, it’s only about an eight by eight room. And the first thing that I can see is this individual in the back corner with a knife in his hand. And he’s trying to open the window, which is connected to the fire escape, but the window’s not opening. And he doesn’t realize it at the time ’cause he’s under so many substances that there’s a piece of wood in the window and he can’t open it. And we learned out later that the two victims were on the second floor and that’s where he was trying to get to. Unfortunately, you know, I guess I could say fortunately for us that the window didn’t open and he didn’t get down there, but that did cause him to turn around. And he saw me standing there and he raised the knife over his head and he ran directly at me. And he was only picking up speed. He was not slowing down. And law enforcement has been learned through studies that if someone is within 21 feet of you, they can get to you even after being shot and still kill or severely injure you.

Brett McKay: When I finally shot him, I was only about three feet away from him, maybe less. There was stippling on his chest ’cause of how close he was. Stippling being the gunpowder burning on his skin ’cause of how close he was. And there was even a point ’cause I took so long that an officer behind me who was a Marine who had been overseas thought that I was gonna freeze and he actually took his gun out, put it over my head to my right ear and shot the guy as well. But what actually helped me in this case later as they start to investigate a police involved shooting was the fact that that Marine was so focused on the knife, which was over this man’s head and was coming down towards my face.

Derrick Levasseur: This Marine was so focused on that knife that he got tunnel vision. And when he shot him, he actually shot him twice in the arm. But the way the bullets went through his arm, it proved that the guy’s arm was over his head when he shot him, showing the trajectory of the bullets going through his forearm from the front to the back, indicating that what I said was actually true. So this happened. Unfortunately, he did not survive those injuries. I have no ill will toward himself [0:41:21.2] ____ Salvin Guardado was his name.

He was probably a good person who just made a really bad decision. And what fortunately helped me in the grand jury proceeding, which happens in every police involved shooting, was that not only did the ballistics support what we were saying, but his family testified on my behalf as well. They knew what was gonna happen that day and it was gonna be him or me. So it was a tough situation for me. Although you sign up and you know that’s a potential possibility, it hadn’t happened in 25 years in my police department. And I left that situation asking myself, why me? And I really struggled with it for a while. I wasn’t a very religious person, but when something like that happens, you start to question where does that leave you? Where do you go from here?

What have you truly done? And if there’s someone who believes in God, where does that put you? And I really started to be concerned about those things on top of the fact that I was waiting to go to this grand jury where these people who don’t know me could ultimately decide to indict me. So it was a really tough time, but through the help of friends and through the help of my church and people around me, I was able to come to an understanding of what transpired and the fact that there was no other choice and I had to do what I did. And there was a point where many people, including officers in my department, who were saying I should retire. I would be able to retire with a 66 and two-thirds pension, non-taxable for the rest of my life.

And ultimately, I decided not to do that clearly ’cause I continued on with my career. But the main reason I did is ’cause one, I felt I was okay with what I did. I’d come to terms with it and I didn’t wanna disrespect any military person or former officer who had been through a similar situation and wanted to stay a police officer but couldn’t ’cause of the mental struggles they now had.

I didn’t have those struggles and I didn’t wanna fake it and I didn’t wanna disrespect anyone who had. So, I came back and I took this really difficult situation and turned it into a positive by using it as a tool to motivate me not only on the job but in life. And honestly, I will tell you many things that I did after that were because of that shooting, including going on Big Brother because when you go through a situation like that, you realize that life is binary. It’s on or it’s off and it can be over in a moment’s notice. You are not promised tomorrow and don’t live life like you are. So, after that time, I really went for everything that I wanted in life, whether it was detective work, whether it was going for my bachelor’s degree and then my master’s degree, whether it was applying for a stupid show like Big Brother, or whether it was just personal things in my life that I wanted to experience.

Being in that moment and realizing how precious life is, you can’t take it for granted. And although this was something I would have preferred to have never happened, I appreciate that it did and I’m glad that I can take something out of it that I’ll carry with me for the rest of my life. That was a very long version of all this, but I think that’s the only way I could tell that story in a context that people would understand without just saying, hey, you shot someone and they died.

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Derrick Levasseur: So that’s my takeaway. I know that was long-winded, so I apologize.

Brett McKay: No, it was good. I appreciate that. Something that you talk about in the book and it stood out to me was you took this moment that could have defined your life negatively for the rest of your life and then you turned it into a catalyst for growth. So, I mean, it really hits home that idea that sometimes our most challenging moments in life can become our biggest sources of strength if we let them. Well, Derrick, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book and your work?

Derrick Levasseur: So the book has been out for a few years. I appreciate you reading it. The Undercover Edge, I believe, is still on Amazon if you wanna check that out. But I would say if you’re interested in what I’m doing, you can go check out Crime Weekly, which is on YouTube and audio, any podcast platform. I also have my own show, Detective Perspective, where we really dive into the unsolved cases that are out there, again, on YouTube and audio. And you can follow me on all the social medias. You just type in my name, Derrick Levasseur, on Instagram, X. I’m there. I’m not a TikToker. You’re not gonna catch me dancing, but I appreciate you allowing me to come on. It was a great conversation and hopefully some people got some stuff out of it.

Brett McKay: Well, Derrick Levasseur, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Derrick Levasseur: Thank you, sir. I appreciate it.

Brett McKay: My guest here is Derrick Levasseur. He’s the author of the book, The Undercover Edge. It’s available on Amazon.com. You can find more information about his work at his website, OfficialDerek.com. Also check out our show notes at AOM.is/undercover, where you can find links to resources and we delve deeper into this topic.

Well that wraps up another edition of the AOM Podcast. Make sure to check out our website @artofmanliness.com, where you can find our podcast archives, as well as thousands of articles that we’ve written over the years about pretty much anything you think of. And if you haven’t= done so already, I’d appreciate it if you’d take one minute to give us a read on the podcast or Spotify. It helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you think would get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, it’s Brett McKay, reminding you to not only listen to AOM Podcasts, but put what you’ve heard into action.