This article series is now available as a professionally formatted, distraction free ebook to read offline at your leisure. Click here to buy.

Welcome back to our series on manly honor.

In our last post, I said that Northern and Southern honor would be covered in one article, and that future posts would be shorter. Neither turned out to be true. Well, this one is a little shorter, but we’re giving Northern and Southern honor their own posts – there’s just too much interesting stuff to cover. And as all my projections have been wrong thus far, I will refrain from making any more moving forward. Just come along for the ride!

An exploration of honor in the American North during the 19th century offers a fascinating framework from which to build on and expand many of the concepts we discussed in our post on Victorian England’s Stoic-Christian honor code, while also digging into the tensions that emerged as a result of its creation – tensions that are still with us today. So if you haven’t read that post yet, I recommend doing so before jumping into this one.

The Stoic-Christian Honor Code in the American North

The Middle and Upper Classes: The Honor of Gentlemen

The North experienced many of the same economic, geographic, and social changes – the rise of industrialization, increased mobility and urbanization, the spread of evangelical Christianity (which took the form of the Second Great Awakening in the US) — that had shaped Victorian England. So this region of the country unsurprisingly experienced a very similar shift in their ideal of honor. Because of the unique nature of the American landscape, the various component parts which made up the new Stoic-Christian honor code in the North were emphasized and de-emphasized in different ways than they were across the pond.

For example, the “gentility” part of the Victorian honor code – an emphasis on education, decorum, manners, style, and above all, “taste” – did not enjoy that same widespread popularity on these shores. For some, a focus on refinement and formal rules of conduct, no matter how nominally democratized, smacked too much of the European aristocracy they had only recently won independence from. Zealous converts to evangelical Christianity found the standards of gentility overly materialistic and worldly. There were also men who thought real manhood required a degree of rough coarseness, and found such refinement effeminate and contrary to the rugged nature of the country, and even its democratic spirit; some worried that outward polish might hide a man’s inner rotten nature, allowing him to get ahead over a man who looked a little rough, but whose heart was true.

On the flip side, the ideal of the self-made man was never as celebrated as it was in America. In a nation of newcomers who were freed from tradition and inhabited a land of great opportunity, the ethic of pulling yourself up by your bootstraps became practically synonymous with the American spirit, and still is. Even at the turn of the 19th century the country already had real-world success stories like Benjamin Franklin to look to, exemplars of the promise that any man who adopted the values of industry, thrift, self-sufficiency, and integrity could rise in the world as far as he wished. For this reason, the virtues and character traits connected with economic success played an even larger role in the North’s code of honor.

The middle and upper classes’ emphasis on earning status through virtuously-won wealth, coupled with the even greater mobility in the North than in England (Americans have been famous for relocating for the sake of opportunity since the country was settled), and the American penchant for individuality and independence, pushed the evolution of honor from public to private even faster in the States. Public reputation still mattered to gentlemen – a history of immoral and lazy behavior could follow a man via letter and gossip and close doors of social and business opportunity. But in a social, economic, and geographic landscape that was increasingly dependent on impersonal relationships, and in which the chief virtue was self-restraint, the need to physically retaliate against anyone who impugned your honor began to seem silly; un-manly, in fact. Who cared what other people thought of you? A man could simply point to the fruits of his labors to rebut a critic. Gentlemen began to assert a self-worth that was less dependent on the opinions of others and more focused on the contents of his conscience. In turn, dueling greatly fell out of favor in the North (although it did not die out altogether), and while a Northern gentleman was still prepared to at least have a fistfight when insulted, he could decide to walk away and still retain his sense of honor. It became a matter of honor to resort to violence only under extreme provocation – the point at which the insult and harassment reached a point that the gentleman could say with a clear conscience that he had “no choice” in fighting back (a subjective standard, of course, that varied from man to man).

Yet despite these slight differences in emphasis and acceleration, the Northern code of honor was very much like that of Victorian England: a standard predicated on civility, piety, morality, Stoicism, and hard work. The watchword of Northern honor, as it was for the English, was self-restraint. This was the virtue that tied the others together; the man who had mastered himself had the discipline to consider how his actions affected others, the will to resist the temptations of sin, the power to control his emotions, and the ability to set aside frivolous distractions and work hard to get ahead. Self-restraint gave a man the defining quality of Northern honor: “coolness.” A Northern gentleman was to be cool in personal and physical confrontations; he didn’t give in to extreme emotions, could laugh off the insults of others, and never caused a scene. A Northern man who suffered a lapse in his self-restraint and failed to be cool would often say he had “forgotten his manhood,” or had been “unmanned” by the incident.

The Northern variety of the Stoic-Christian honor code also paralleled its English counterpart in that it was adopted by both the middle and upper classes, but did not reach very far down into the working class. Those on the lowest rung of the socio-economic ladder in the North — who more upper-class gentleman referred to as “the roughs” — had an honor culture too, but it was very different than that of their well-heeled brethren.

The Working Class: The Honor of Roughs

Honor for the roughs was very much like the primal honor of ancient times – centered on physical prowess and strength, and proven through physical feats and plenty of fighting. The austere self-control of the upper classes was disdained, and camaraderie was built through unchecked aggression, boisterous noise, rowdy behavior, heavy drinking, and licentious indulgence. In place of the middle-class emphasis on sentimentality and sincerity, roughs engaged in constant mocking, teasing, and what one contemporary called “relentless sarcasm.”

Roughs were always challenging and testing each other and getting into brawls to prove who was stronger and more “game.” Honor was premised on never letting another man dominate you. At a great remove from the white-collar work of the expanding middle class, roughs earned honor and status through the giving and receiving of pain, as they were either unable or unwilling to acquire it through the climbing of the economic ladder. More well-off gentlemen thought it was the latter; because a central tenet of the Stoic-Christian honor code was its democratic nature – that any man who so willed it could, at least hypothetically, cultivate its traits – men who refused to do so were shamed, and seen as despicable.

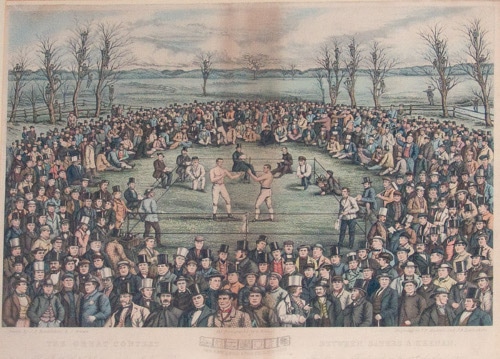

Physical culture was a point of contention for gentlemen. Some thought it too working class and vulgar, while others believed working out at a gymnasium was an excellent way to release the masculine energies a man was restraining in other areas, while also building up more discipline at the same time. Boxing was a particularly debated pastime. Some though it too violent for gentlemen to partake in or watch, and it was banned in many states. Other gentlemen thought it was a healthy way to keep oneself from becoming too soft and refined.

While there was debate among adherents to the Stoic-Christian honor code as to whether things like drinking, swearing, gambling, and fighting were compatible with true manliness, there were plenty of men in every class who enjoyed such things, and felt they were, along with a little scrapping and hazing, good for manly camaraderie. But even gentlemen who indulged in such “vices” scorned the roughs, for they did not balance such activities with more civilized and refined qualities. As Lorien Foote put it, many Northerners believed that true manliness “combined the ‘soft’ virtues of womanhood with the ‘hard’ virtues of manliness.” Or as a writer from the time argued, “Always with the highest courage there lives a great pity and tenderness. The brave man is always soft-hearted. The highest manhood dwells with the highest womanhood.” A man was to be both brave and moral, strong and kind, stoic in crisis and affectionate at home. As civilization had progressed, the markers of manliness had shifted from those that most harkened to the savage – strength and aggression – to those that set a man apart from his primitive origins – a shift from more biological traits to those which required higher cognitive power, reason, and willpower to earn. Thus, because of the roughs’ lack of tenderness, constant need to fight, and unchecked aggression, gentlemen saw them as degenerate, immoral brutes whose lack of self-restraint made them little higher than the beasts – and unworthy of the designation of honor, and, the title of man.

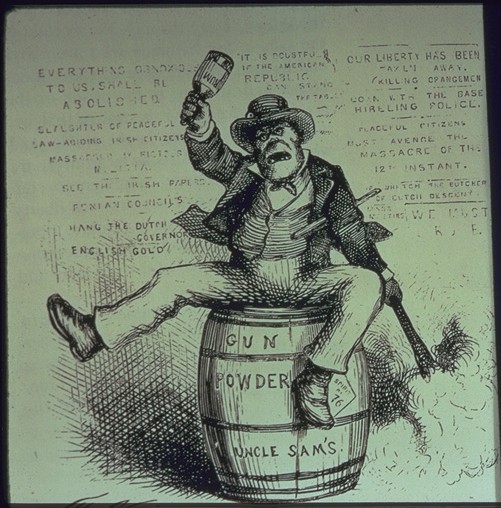

That middle and upper class gentlemen not only rejected the working class as equals, but as fellow men too, can be seen in cartoons of the time which often depicted the Irish as apes.

From the founding of the country, American leaders had argued that the strength and vitality of the nation – this new experiment in democracy– was directly dependent on the virtuous manhood of its citizens. That virtue originally centered on civic-mindedness and involvement — having a true stake in society — and the ability to set aside selfish concerns for the common good, and had evolved to include other virtues as well, like moral character and economic independence. Gentlemen thus saw the roughs as dishonorable because they believed their economic dependence, lack of education, and penchant for savagery and vice could lead, ultimately, to the failure of the republic.

With this great divide between the two honor groups, the gentlemen and the roughs did not often interact, and fairly inhabited two different universes. That would all change, cause great conflict, and widen the divide even further when they were forced to serve together during the Civil War.

The Gentlemen and the Roughs During the Civil War

The North’s two competing ideas of manhood – one undomesticated and primal, the other restrained and moral — came into direct conflict during the course of the Civil War.

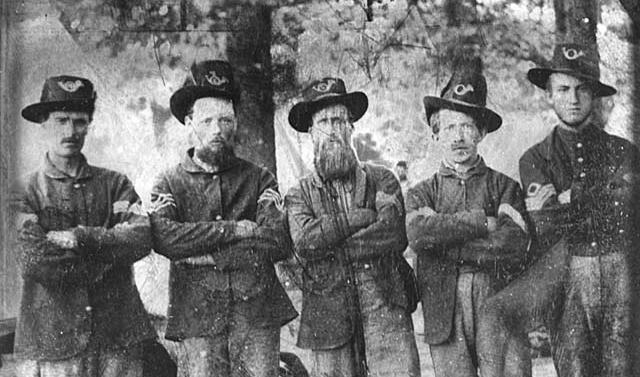

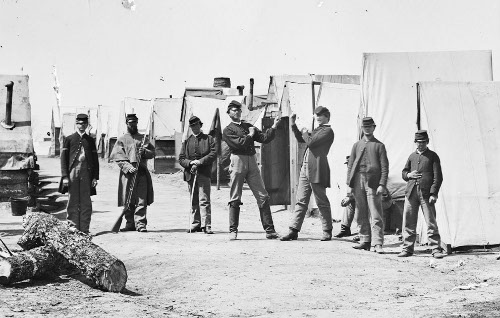

When the war first broke out, volunteers made up the Army’s ranks — men driven by a sense of honor and duty to fight for the Union. Well-educated gentlemanly elites from New England’s middle and upper classes signed on to lead regiments largely composed of men from a similar socio-economic background.

But once the draft was enacted in 1862, the Army was flooded with conscripts — 2/3 of which were immigrants — who came from the lowest tier of Northern society (well-off men who were drafted could pay for a substitute – again invariably a man from the working class — to serve for them). The Army’s ranks were greatly diversified, creating a common scenario where refined, morally upright middle and upper class gentlemen had command over an enlisted group of hard-drinking, oft-fighting, working-class roughs.

A clash in codes of honor arose. You had one company of men sitting quietly at temperance society meetings or scripture study, and another going off to drink and wench and brawl, and then coming back to bust up the temperance meeting and pour mule urine on the teetotalers. On the one hand you had 17-year-old chaps like Charlie Brandegee, who was aghast at the amount of profanity in the army, and wrote to his father: “I have not used any form of swearing since my arrival, although I have it on every side. There are 100 men in this co. on an average each man uses 25 oaths [swear words] a day — 2500 oaths a day! I have always protested against profane language and think there is less swearing in our tent than in any other. Whenever anybody commences to swear the rest sing out ‘English language, English language in this tent.’” (Interesting fact: 5,223 men were court-martialed for the use of profanity during the war, in violation of the 83rd Article of War requiring conduct appropriate to one’s status as an “officer and a gentleman.”) On the other hand, you had men who cheekily formed anti-temperance societies, that pledged “to destroy (by drinking) all the liquor they could get,” and created anti-moralizing clubs like “The Independent Order of Trumps,” whose bylaws proclaimed that members would always act with decorum, and then added: “drinking, eating, smoking and chewing will be considered decorum.” The Trumps “resolved to acquit ourselves like men, and other things.”

A Clash of Manhoods in the Union Army

The two groups eyed each other warily. Each had absorbed the American ideal of all men being created equal, and each wanted their manhood to be recognized by the other. But the gentlemen thought the roughs were brutes, and the roughs thought the gentlemen were effete; neither would acknowledge the other’s respective code of honor. This tension, understandably, would often compromise the unity of Northern regiments.

As aforementioned, the strength and vitality of the American republic had, since its founding, been linked to the virtuous manhood of its citizens. The North believed it would win the war because of the superior character of its citizens. Thus, the roughs’ unapologetic revelry in vice and licentiousness was seen by gentlemen as draining vital virility from the Union effort.

What had been more of an abstract concern before the war crystallized into a more immediate worry during it; gentleman commanders felt that the roughs’ drinking and lack of discipline prevented them from becoming effective soldiers, and thus compromised the chances of Northern victory on the battlefield. Adherents to the Stoic-Christian honor code believed moral courage and physical courage were linked, and that without the former, the roughs would have to be physically compelled to fight and would drag the Union army down with them.

Soldiers in the Union Army not only fought the South, but each other as well. See here for a not so uncommon story about one company getting into a “bench clearing” brawl with another.

In a way they were right. The roughs’ honor code of aggression and physical prowess was suited to the battles of primitive man – when war parties consisted of a group of equal peers, the fighting could be flexible, impromptu, and hand-to-hand, battles were infrequent and short-lived, and the reason for fighting was the protection of the tribe and the defense of kin.

The Civil War, on the other hand, was a modern battle that bore little resemblance to the primal skirmishes of old. Men served in a strict hierarchy, stood in organized battle lines to face increasingly mechanized and impersonal weapons, and fought not for the immediate protection of kin, but for abstract principles of union, democracy, and patriotism. In this new type of war a soldier had to be able to obey orders from a superior, fight out of duty, and have the self-control — the “coolness” — to hold the line as cannon fire ripped through the ranks. Unfettered aggression, a plus for primal man, now had to be corralled through proper channels.

A man also had to be in battle-mode not simply for days, but for years — living away from family in spartan camp life. In such conditions, raw courage became less important in earning honor than a man’s ability to bear suffering.

Unsurprisingly then, the roughs rebelled against such demands, and saw little in the war that benefited themselves. They were reluctant to give up the equality of their honor group, and felt that submitting themselves to their officers – whom they often referred to as the “shoulder-strap gentry” — resulted in a loss of manhood. They believed status had to be earned through competition, but many of their commanders had gotten their positions through influence and family connections. Their code of honor did not allow them to let another man falsely claim status and thus domination, and they would have loved to have brought their elite officers down a peg. But they were frustratingly forbidden from establishing their honor in the way they desired — by having a physical throwdown. They would often tell an officer whom they felt was lording their authority over them that if it weren’t for his shoulder straps, he would have given the man a merciless pummeling. For example, Union soldier John Clute told his Captain, Daniel Link, “If you will lay off your shoulder straps I will give you a damn good whipping.” Another soldier told an officer, “All that saved you was your shoulder straps, if you hadn’t them on, I would whip you in a minute.” Sometimes privates couldn’t control this urge to physically lash out; striking a superior officer was in fact the second-most common offense during the war.

Enlisted men also sometimes joined together in rebellion against officers they felt abused their authority; 2,764 men were charged with exciting, causing, or joining in a munity during the war. And these numbers greatly underestimate the true number of such cases, as the majority were likely given an immediate punishment or tried with a regimental or field-officer courts-martial.

Rough soldiers also resisted the authority of their gentlemen officers in less violent ways. They were slow to obey orders, talked back when they received them, refused to salute, and would yell and even make farting noises when their officers tried to talk. Complete desertion was also quite common.

For their part, officers were not above using violence themselves in order to compel obedience from their men. As Lorien Foote writes, “Because army regulations sanctioned the use of physical coercion from officers when inferiors disobeyed lawful orders…Officers grabbed, hit, kicked, and pulled swords on recalcitrant enlisted men.” Some elite officers shot disobedient men outright, and some regiments established the position of “file closer,” whose job it was to hold the ranks during battle by shooting or bayoneting any soldier who straggled or tried to flee from cowardice.

Conclusion

At the end of the War Between the States, the North had bested the South, while in the battle between two competing codes of honor and manliness, the gentlemen had triumphed over the roughs. Having already ascended prior to the war, the Stoic-Christian honor code consolidated its status as the North’s cultural ideal. Those in the middle and upper classes believed, as Foote writes, that “The men who had truly saved the Union…were its gentlemen, men with domestic virtues, moral character, and proper manners.” They had pulled out the victory, despite the dangers the roughs had posed – men whose lack of discipline and indulgence in vice had, Stoic-Christian gentlemen believed, threatened the strength of the Union Army, and in turn, the future of the whole nation.

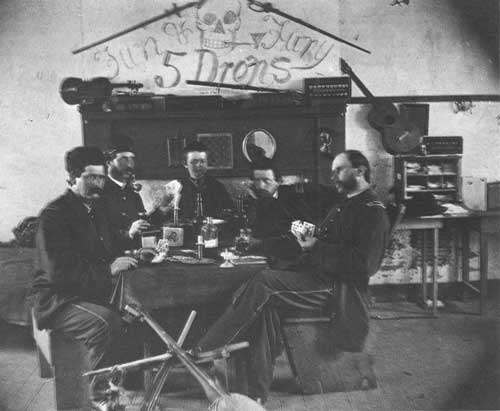

Things like drinking, and even playing cards were gray areas among those who aspired to be gentlemen. Some embraced such vices in moderation, while others thought it was honorable to abstain entirely.

But it’s important to point out that the above discussion represents a simplification of the issues surrounding honor in the North during this period. The gentlemen and the roughs represent extremes on a spectrum of manliness, and there were plenty of men whose codes of honor fell somewhere between them. All classes agreed on the necessity of physical courage to manhood. And outside the roughs, there was general agreement about the importance of good character – being honest, hardworking, resolute, and respectful to others. But beyond that was a gray area. Some men believed that things like strict purity, temperance, and proper manners were important parts of the code, while others enjoyed swearing, drinking, fighting, and oat-sowing in moderation, and didn’t feel such indulgences compromised their honor, or even their designation as gentlemen.

The reason I wanted to flesh out the subject of Northern honor in the 19th century is that the question as to where to draw the line on the spectrum of manliness is still very much with us today. In fact, I get a front row seat to it with the feedback we get on our posts. “How to dress with style? Real men don’t care about how they look!” “How to field dress a squirrel? Real men don’t kill innocent animals. Do more about style!” “Gambling? That’s immoral! Real men never gamble!” “Etiquette? Real men do whatever they want to do!” “A real man saves himself for marriage.” “A man should be able to have sex with whoever he wants to, as much as he wants.” “Swearing is manly!” “No it’s not!” “What does it mean to be a man? A real man doesn’t think about it. Do more practical stuff.” “Your philosophical posts are the most important. You should do more of them.”

The heart of the debate both for the 19th century man and for today’s, is whether manhood, and thus the honor code of men, should be based on primal, biological traits or in our capacity for higher virtues. The first type of manhood is made up of instinct, aggression, virility, violence, strength, and the need to earn status through physical prowess and martial courage — the essential traits that all men shared anciently, and transcend culture and time. Here manhood is defined as what is unique from womanhood. The second type roots manhood in the ability to overcome lower urges and master self – the cultivation of the higher traits of mind and character that separate man from beast, and man from boy. The type of manhood one ascribes to influences one’s view of what is good for men; as Foote puts it: “Within this complex discourse, some men feared that excessive civilization produced weak, decadent, and effeminate men, while others warned that those who had not developed civilized restraint and refinement were savage boys rather than fully developed men.”

No matter how messy, the possibility of combining the virile traits of essential manhood with the moral virtues has been explored since ancient Greece, and is a tradition we continue today, and will explore more in the last post in this series. But for now, next up is a look at Southern honor.

Manly Honor Series:

Part I: What is Honor?

Part II: The Decline of Traditional Honor in the West, Ancient Greece to the Romantic Period

Part III: The Victorian Era and the Development of the Stoic-Christian Code of Honor

Part IV: The Gentlemen and the Roughs: The Collision of Two Honor Codes in the American North

Part V: Honor in the American South

Part VI: The Decline of Traditional Honor in the West in the 20th Century

Part VII: How and Why to Revive Manly Honor in the Twenty-First Century

Podcast: The Gentlemen and the Roughs with Dr. Lorien Foote

______________

Sources:

The Gentlemen and the Roughs: Violence, Honor, and Manhood in the Union Army by Lorien Foote (A fascinating read)