Miss Part I? Read it here.

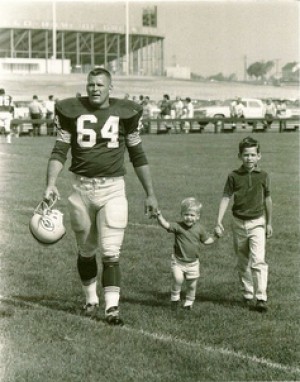

On December 31, 1967, the Green Bay Packers and the Dallas Cowboys met on Lambeau Field for the NFL Championship. Later dubbed the “Ice Bowl,” temperatures hovered at 13 degrees below zero, the turf was as hard as rock, whistles stuck in referees’ mouths, and members of the halftime band were sent to the hospital for hypothermia. It remains the coldest NFL game on record.

For sixty minutes, these rival teams duked it out, with each player digging deep to summon the fortitude to battle both the cold and the opposing team. With sixteen seconds left in the game, the Cowboys held a 17-14 lead, and the Packers had the ball. On 3rd and goal, Bart Starr executed a quarterback sneak with offensive lineman Jerry Kramer giving him the block needed to get into the end zone and win the game. The Packers had made it to another Super Bowl.

That block has been called the greatest in NFL history. Yet Kramer didn’t dance around or pull a Sharpie out of his sock to sign an instant autograph; he simply walked off the field.

There was no need for such outward expressions–the satisfaction of a hard-fought win was enough.

How to Celebrate with Grace

Last time, we talked about how to lose with dignity.

It’s a difficult thing to do, but in some ways, it can actually be easier than celebrating with grace. When you win a great victory or attain a noteworthy achievement, it’s hard to strike the balance between genuinely enjoying your success and not adding to your opponent’s misery or coming off as a smug braggart. Here are some recommendations on how to walk that line.

Should you celebrate publicly or privately?

This is one of the big questions people struggle with in regards to celebrating with grace–should you display your adulation publicly or keep it to yourself?

The answer to that question depends on what kind of accomplishment it is, and whether you are in direct competition with those around you.

When an accomplishment is of the type that places people into “classes,” (things like grades, salary raises, promotions, and try-outs) it is generally better to keep your celebration private (to be enjoyed by yourself and close family and friends). So for example, when the teacher hands you back an A+ paper, there is no need for a whoop and a fist pump–just smile and put the paper away. The more competitive something is, the more true this rule becomes–which is why people never talked about their GPA or rank in law school.

Rubbing your win in your competitors’ faces in these situations will not make your achievement any more real–it is merely an attempt to stroke your ego and tends to create rancor with your peers.

Of course there are situations where it is appropriate to celebrate in front of your opponents–such as the award ceremony or sports game–as the competition is the raison d’être for these events, as opposed to being unspoken.

Even when your success can appropriately be celebrated publicly, use discretion, particularly when using social networks like Facebook and Twitter. These mediums have made news-sharing so easy that some folks have gotten confused about what constitutes actual news. Most people genuinely want to hear about what’s going on in your life and your success, they just don’t think that having an awesome bowel movement constitutes a singular achievement.

Appreciate those who helped make it happen.

The humble man realizes that even when praise for a victory falls entirely on him, there were people along the way who helped make it happen. The star player thanks the team; the boss thanks his employees.

Show gratitude in general.

Celebrations come off as smug when the victor acts as if he were entitled to the success he’s found. The dignified man is proud of the work he did to get where he is, while also being forever grateful that he was in the right spot at the right time and a confluence of factors came together in his favor.

Acknowledge the loser.

Shake the hand of your fallen opponent. If you chat, focus on the game itself, instead of on the outcome. And as an old Esquire etiquette guide advises, “In the conventional exchange of remarks at game’s end, the good loser compliments the winner on his skill and the good winner sympathizes with the loser on his luck.”

Don’t disparage your victory.

The man who trivializes his win can be as much of a pain as the one who lords it over you. While acting like you didn’t deserve to win or it isn’t a big deal might seem like the “nice” thing to do or something that will deflect attention, it only ends up making the victor look even better–“Not only did he win, he’s so above it all he doesn’t even care!” And it adds insult to your opponent’s injury. As a loser, I want to know I was a worthy foe, and that you actually wanted to win, because I certainly did!

When George C. Scott won an Oscar in 1970 for his portrayal of George S. Patton in the film that bore the general’s name, Scott became the first person to turn down an Academy Award, saying he was not in competition with other actors and that the ceremony constituted a “two hour meat parade.” This surprising move put more attention on Scott, not less (it dominated the news for a couple of weeks–even garnering the cover of Time), and it sent a message to the other nominees that not only did they lose the award, they were losers for even caring about winning!

Share in the rewards.

When a gambler makes money, he often tips the dealer. It’s good karma. When something good happens to you, spread the love. If you get a great promotion at work, take all of your friends out for drinks on you.

Don’t do the “humble brag.”

Some people try to split the difference between celebrating something, and not wanting to boast, by employing the “humble brag.” The humble brag is where you’re really boasting about something, but you try to disguise this fact by throwing in a complaint or a self-deprecating aside.

Humble bragging is especially popular on social outlets like Twitter and Facebook. Here are some examples compiled by the Twitter account Humblebrag:

Humble brags are so prevalent on things like Twitter and Facebook because folks sometimes use these platforms not to share updates, but to craft a persona and shape the way others see them. A humble brag is typically used online in order to share “news” that isn’t really news at all, but serves to show people that you’re doing something cool, and you’re the kind of person who does X.

Humble brags are so prevalent on things like Twitter and Facebook because folks sometimes use these platforms not to share updates, but to craft a persona and shape the way others see them. A humble brag is typically used online in order to share “news” that isn’t really news at all, but serves to show people that you’re doing something cool, and you’re the kind of person who does X.

Whether you’re sharing news of your success in the real world or online, it’s best to deliver it straight up. You may worry about coming off as smug, but it’s actually better to come off as smug, than to appear as someone who’s smug but trying to hide it. People are more annoyed by duplicity than pride.

Really, the best rule to follow here is one that will serve you well in all areas of your life: if you feel you have to cover up what you’re doing, even a little, that’s a sign you shouldn’t be doing it at all.

Resist the “How do you like me now?!” impulse.

When you achieve something that people all along the way doubted you could do, it’s very tempting to rub it in their faces. “How do you like me now, haters?!” And undoubtedly, talking about the obstacles that stood in your way on the road to the top can be appropriate, especially when it serves as inspiration to others. It’s neat to hear that some successful upstart got turned down 30 times by investors before becoming a billionaire dollar biz. But this shouldn’t be the focus of your celebration; otherwise, this behavior inevitably makes you look bitter and tarnishes your reputation.

Exhibit A: Michael Jordan’s Hall of Fame acceptance speech. Jordan could have given a speech like those who preceded him the night he was inducted—John Stockton and David Robinson. Their speeches were filled with gratitude for those who had helped them during their illustrious careers. Instead, Jordan used his speech to criticize the teammates who froze him out of the 1985 All-Star game when he was a rookie, the college coach who chose other players to appear on the cover of Sports Illustrated, and the Bulls general manager for saying that organizations and not individuals win championships. He even flew out the now grown man that his high school coach had bumped him off the varsity team for his sophomore year, just to be able to point to him and say to his old coach, “I wanted to make sure you understood: You made a mistake, dude.” That was his message to everyone: “Haha—you guys were wrong!” But Jordan’s record already said that loud and clear; showing he was still bothered by such slights made him seem petty instead of magnanimous.

Don’t punish the loser further.

The victory is enough; there’s no need to kick a rival when he’s down.

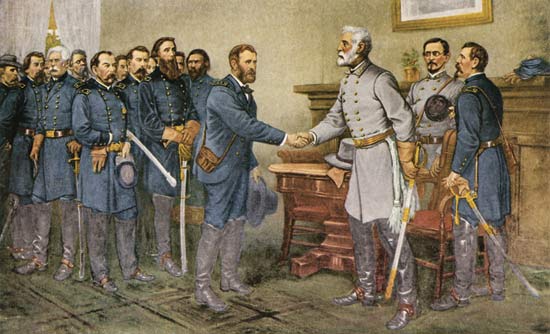

After General Lee surrendered at Appomattox and General Grant shared the news with his troops, the men started shooting their guns in victory. Grant asked them to cease firing, saying, “The war is over, the rebels are again our countrymen, and the best way of showing our rejoicing will be to abstain from all such demonstrations.”

He also decided not to go through Richmond on his return to Washington D.C., as he did not wish to do “anything at such a time that would add to [the South’s] sorrow.”

Some folks cannot be helped.

It’s gentlemanly to want to avoid coming of as Smugly McSmugs Alot and to make an effort to celebrate with grace. But keep in mind that no matter how tactfully you handle your success, there are always going to be folks who feel you’re stuck up. They’re jealous and projecting those feelings on you. Don’t worry about it.

Lose with Dignity, Celebrate with Grace

The ability to lose with dignity and celebrate with grace is rare in our society, but examples of gentlemanliness remain. Case in point: Delaware’s “Return Day.”

The ability to lose with dignity and celebrate with grace is rare in our society, but examples of gentlemanliness remain. Case in point: Delaware’s “Return Day.”

The Return Day tradition started in 1791 when Georgetown was established as Delaware’s County Seat. Residents of Sussex County had to travel there on Election Day to cast their ballots. Two days later after the votes had been tallied, folks returned to Georgetown to hear the results announced. Carnival-esque festivities attended the reading of the winners.

The tradition still continues today. On the Thursday after Election Day, businesses and schools close and Delawareans from all over the state converge on Georgetown for the Return Day festivities. There’s an ox roast, a hatchet-throwing contest between town mayors, and a most unique parade.

The winners and the losers of each political race put aside the rancor of the election and sit together in horse-drawn carriages that make their way through town. And then the chairmen of the Sussex County Republican and Democratic parties meet together to literally bury the hatchet. Each grasps the handle of a hatchet, and together they plunge the weapon in a box of sand.

A great tradition, I think. For it symbolizes the fact that makes it possible for each of us to lose with dignity and celebrate with grace: no matter how small or large the contest, life goes on.