At age 20: Bill Gates dropped out of Harvard and cofounded Microsoft, and Sir Isaac Newton began developing a new branch of mathematics.

At age 21: Thomas Alva Edison created his first invention, an electric vote recorder, Steve Jobs co-founded Apple Inc., and Alfred Tennyson published his first poetry.

At age 22: Inventor Samuel Colt patented the Colt six-shooter revolver, and Cyrus Hall McCormick invented the McCormick reaper, which allowed one man to do the work of five

At age 23: T. S. Eliot wrote “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” John Keats penned “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” and Truman Capote published his first novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms.

At age 24: Johannes Kepler defended the Copernican theory and described the structure of the solar system.

At age 25: Orson Welles conscripted, directed, and starred in Citizen Kane, Charles Lindbergh became the first person to fly alone across the Atlantic, New York farmhand Joseph Smith founded the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, John Wesley began planting the seeds for Methodism at Oxford, and Alexander the Great became the King of Persia.

At age 26: Albert Einstein published five major research papers in a German physics journal, fundamentally changing man’s view of the universe and leading to such inventions as television and the atomic bomb, Benjamin Franklin published the first edition of Poor Richard’s Almanac, Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin, and Napoleon Bonaparte conquered Italy.

An impressive list of accomplishments to be sure. And despite how many might interpret this kind of “precociousness,” I would argue that these men accomplished what they did not despite their age, but because of it.

A Disposable Decade?

Maybe you’ve heard it said, or even said it yourself: “Thirty is the new twenty.”

Things that were once markers of maturity in the past — finishing school, landing your first “real” job, getting hitched, having kids, buying a house – are getting pushed back later in life. Instead of hitting these milestones in one’s early or mid-twenties, as our parents and grandparents did, economic, sociological, and cultural factors have postponed these steps for many until the latter part of the decade, and into one’s thirties.

This has opened up an unprecedented period of time and development for young adults. The twenties have been relabeled “emerging adulthood” or “extended adolescence,” and because of its nascent nature, there aren’t a lot of guideposts on how a man should spend this new stage of life.

In the absence of such guidance, the twenties have come to be seen as a time to dabble, drift, and adventure, with the idea that you can get serious about stuff later — once you hit thirty. Thus, the twenties have been branded as disposable — an inconsequential holding period between two decades of schooling and becoming a “real” adult.

But the idea that one’s twenties are unimportant couldn’t be farther from the truth. In fact, “thirty is the new twenty” is one of the biggest lies of our age.

In this two-part series, we’ll explain why.

This Is Your Brain in Your Twenties

The prevailing view these days is that people used to get started in life earlier simply because the economy allowed it, or that “the Man” shamed people into quickly becoming a grown-up instead of spending time being free, having fun, and exploring, and, since these factors are no longer in effect, there aren’t any good reasons for making important and consequential decisions and commitments in your twenties anymore.

While that explanation of why milestones have been delayed has truth to it, there does in fact remain very compelling reasons for beginning to shape life’s most important elements while still in your twenties – and they don’t have anything to do with culture or economics. Rather, they’re biological, and thus timeless — they apply just as much to the 1950s as to today. Now we could delve into one aspect of biology as it concerns delayed adulthood – that of reproduction – as it isn’t just affected by age for the ladies; aging male sperm is thought to be responsible for mutations that lead to things like autism and schizophrenia. But we’ll cover that important topic another time.

Today I want to center our discussion on something that transcends fatherhood, and affects all the big life decisions you’ll make – particularly as it concerns things like career and relationships, even faith. And that’s the twentysomething brain.

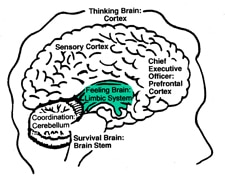

The human brain develops from bottom to top and from back to front. At the bottom-center sits the limbic system, in which resides some of the more primitive parts of our brain, areas that are responsible for things like sleep, hunger, emotions, sex, and pleasure.

Located at the front of the brain is the prefrontal cortex. Last to develop, it is often referred to as the “CEO” of the brain – the executive of the mind. It helps you do things like process probability, regulate emotions and impulses, delay gratification, handle uncertainty and abstract goals, plan for the future, and make good decisions and judgments.

During adolescence, both parts of the brain swing into action and interact as they move you towards adulthood. The limbic system revs up your feelings of emotion, motivation, and the craving for reward, causing your teenage self to feel restless and increasing your desire to do big things, take risks, experience everything, forge friendships, and become independent from your parents. At the same time, your prefrontal cortex begins its final maturation and starts to act as a check to these new surging impulses, attempting to keep you from doing anything too stupid. (The New York Times has a neat interactive webpage showing your brain maturation from childhood to young adulthood.)

This is why young adults often seem capable of great maturity at some times, and then do bone-headed things at other times – the impulsive and CEO parts of their brains are having a tug-of-war, and sometimes one wins, and sometimes the other does. For this reason, your personality is kind of uneven during this period.

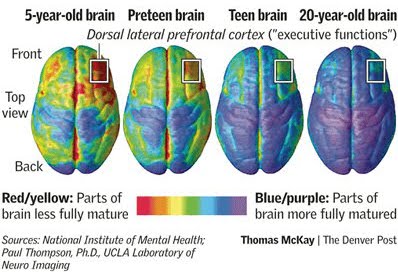

In your early twenties, your prefrontal cortex is almost finished maturing, but not quite.

It used to be thought that the prefrontal cortex finished developing during the teen years, but we now know that its maturation isn’t complete until around age 25. What this means is that from approximately ages 15-25, you’re walking around and experiencing the world with an “adolescent” brain. This is why almost all of us can look back at episodes not only from high school, but also from college, that make us shake our heads and ask: “What was I thinking?!”

Now, you might gather from all this that it’s best to wait until your thirties to make big decisions after all — until your prefrontal cortex is fully formed and mature. But this isn’t the case, for as one neurobiologist put it, your twenties are not simply a time of “enormous risk,” but also one of “enormous opportunity.”

What are those enormous opportunities that your twentysomething brain offers you? There are two big ones – and they only come around once in a lifetime. First is the opportunity to passionately and uninhibitedly go after big goals, figure out life’s big questions, and make important commitments. Second, is the opportunity to take an active role in the development of the executive part of your brain in order to create a foundation for lasting success. (These brain advantages apply to teenagers too, obviously, but twentysomethings have a lot more leeway to make their own decisions and thus exercise their brains’ special powers. They’re at the crossroads of opportunity and independence.)

In today’s post we’ll be focusing on the first advantage of the twentysomething brain; tomorrow, we’ll delve into advantage numero dos.

Twentysomething Brain Advantage #1: The passionate, uninhibited motivation to fearlessly go after your passions, figure out life’s big questions, and make important commitments.

It may seem like a cruel twist of nature that at the same time you are feeling motivated to take risks and seek rewards, are experiencing a surge in emotion, and are beginning to grapple with the complexities of adulthood and make decisions that will influence your whole future, the executive part of your brain isn’t up to speed yet — as if you’re driving a car with faulty brakes. And indeed, that’s how researchers long saw it – that the adolescent brain was “broken” – recklessly and pointlessly impulsive.

But more recent research has shown that the same qualities of the adolescent brain that can be liabilities, can also be distinct advantages – not accidents of nature at all, but purposeful evolutionary adaptions. That purpose is to get a young adult to venture from home, strike out on his own, explore new turf, and take chances in the search for success. Those able to successfully harness the unique energies of youth have, from time immemorial, gained an edge over their peers. As neuroscientist B.J. Casey put it, the “unbalanced” nature of the adolescent brain is “exactly what you’d need to do the things you have to do then.”

What kind of powers does the adolescent brain give you that you need as you venture into adulthood? There are three:

- Fervent passion

- Fearlessness in the face of risk

- A keen and thoughtful curiosity about people and the world

Deep Passion

As we’ve discussed, during adolescence the limbic system of the brain starts amping up your feelings of emotion and motivation, while at the same time the prefontal cortex begins to develop its capacity to check the impulses the former generates. And again, the frontal lobes complete their maturation around the mid-twenties. Before that time, the limbic system, particularly the amygdala, reacts more strongly to stimuli than it does in adults. While the frontal cortex generates a “thinking” response, the amygdala produces a more emotional, gut-oriented reaction.

Neurobiologists aren’t sure of the exact relationship between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex in the adolescent brain (and remember, this is the brain from ages approx. 15-25), beyond the fact that the latter becomes more strongly activated as it matures and begins to act as a greater and greater check to the former.

But I like to imagine the set-up in this (totally unscientific) analogy: The prefrontal cortex is like a sieve. In the adolescent brain the holes in the sieve are large, so that stimuli from the outside world mostly goes right through, and lights up the amygdala, creating an emotional, gut reaction. As the frontal cortex matures and strengthens, the holes become increasingly small – the net catches and analyzes more and more of the stimuli before it hits the amygdala, giving the brain the chance to come up with a rational, measured response. Indeed, the prefrontal cortex is also known as the “area of sober second thought,” as it is the part of the brain that weighs the consequences of a choice.

This is why in your teen years, up through your early twenties, you experience things really intensely – relationships are intense, spiritual experiences are intense, emotional highs are high and lows are low. New experiences feel amazing; thrills give you more of a rush. Stimuli from the world goes directly into the brain instead of being caught in the cortex sieve and dryly analyzed first. Experiences are able to light up your emotional amygdala, allowing you to feel things deeply. Here you have the neurological reason behind the famously fervent passion of youth.

The intensity of the adolescent brain can make our teenage years and early twenties feel overly dramatic. But this passion also allows twentysomethings to feel strongly about issues, causes, people, and spirituality. It can drive you to start movements, take action, and make commitments – steps which are then facilitated by the next twentysomething brain power.

Listen to my podcast with author and psychologist Meg Jay:

Fearlessness in the Face of Risk

In addition to the intensity and emotion the amygdala brings to the equation, the reward centers of the brain are also highly sensitive during this time. This drives you to take more chances.

Contrary to popular belief, adolescents actually overestimate some risks – those of the “known variety,” like the risk of getting pregnant or getting an STD. But they underestimate “unknown” risks – anything where the likelihood of winning and losing is ambiguous.

Adults will often shut down the idea of such risks as soon as they cross their minds, but an adolescent will take time to really consider them.

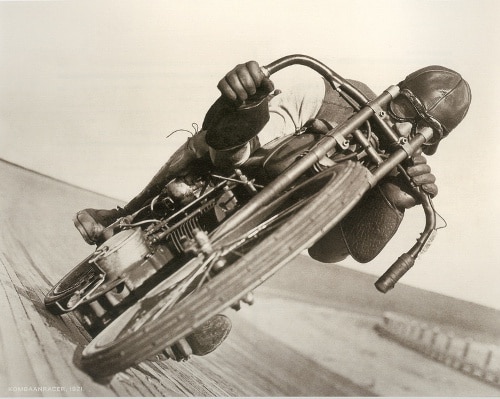

Obviously, this penchant for risk-taking can have a down-side — there’s a reason the mortality rate for adolescents is triple that of grade-school children. But, fearlessness in the face of risk can also be absolutely necessary in getting you to go after your dreams and ideals.

Making any big decision or commitment involves risk – will my business fail, is she the one, will I be happy a thousand miles from home? And risk kicks the prefrontal cortex into high gear – “What if this happens? What about x,y,z?” Obviously, rational analysis is a great thing, but there are some things in life where you just have to push down your fear and take the plunge. The twentysomething brain gives you the fearlessness to do so. But as the prefrontal cortex gathers strength, it starts to talk you out of doing anything risky and is more inclined to maintain the status quo. Paralysis by analysis sinks in.

A Keen and Thoughtful Curiosity About People and the World

Now you may be thinking, “Sure, twentysomethings have the passion and the courage to make big decisions, but they’ll probably make the wrong ones, because they’re naive and impulsive! Better to wait until you’re older.” And it’s true that researchers have found that sometimes the reward-seeking adolescent brain does make more reckless decisions, like choosing to engage in binge drinking or unsafe sex. But that’s typically because of social pressure (the young adult brain is also more sensitive to the judgment of their peers). Researchers have actually found that in other, less peer-driven and “heated” situations, when a reward is at stake, a young adult desires to get something right, and will actually take longer to decide, and gather more information before doing so, than adults. Which means, researchers say, that there are scenarios where adolescents will potentially make better decisions than “grownups.”

The sensitive reward centers of the adolescent brain not only motivate the process of gathering and pondering information, they also facilitate the learning of new information, which is why adolescents (when it comes to a subject they enjoy, anyway) can find studying more pleasurable and satisfying than adults.

All this makes sense: who spends more time willingly examining questions like what’s the true religion and what’s the best political philosophy – college students or their parents? The latter often cannot be bothered, while the former can’t get enough of delving into life’s big questions. Because of the sensitive reward system of the adolescent brain, things that feel like drudgery to “grownups,” like seeking truth, are deeply rewarding to young adults.

Taking Advantage of the Tripartite Powers of the Twentysomething Brain

I like to think of things like starting your own business, landing your dream job, getting married, committing to a faith, and even catalyzing a cultural or political movement, as akin to traveling to space. Once your rocket leaves the earth’s atmosphere, it can orbit there indefinitely. But to reach outer space in the first place, you need a huge, powerful force in the form of rocket thrusters in order to overcome the earth’s strong gravitational pull.

Well, your twentysomething brain is that rocket thruster.

Twentysomethings are less daunted by unknown risks, and become more motivated and thoughtful by the prospect of reward, while adults are the opposite. During your twenties, you’re passionate and ready to learn, and your greater tolerance for risk pushes you to act on that passion and knowledge.

Unfortunately, your brain’s rocket’s fuel is leaking out as you approach thirty. The time for lift off is now.

Why Your Parents Are Such Squares

Now you finally have an explanation to an observation you probably made growing up: “Man, my parents are so boring. They don’t seem to ponder deep things or be that passionate about anything. They always stick to their routine and are still listening to the same music they did in college! I’ll never end up like that.” You probably thought their steady lameness was a function of their actively deciding to “settle,” or the result of the way their responsibilities had worn them down. These things are certainly factors in Adult Boring Disorder (ABD). But it’s also because of changes in their brains, changes that will happen to you, too.

Most adults are so “boring” and risk-averse and don’t experience life as intensely because the sensitivity of the reward centers in their brains have dulled and their mature prefrontal corti have put the lid on their emotional passions. Your parents’ musical tastes ended in college (at least this is my personal theory on the matter) because music doesn’t produce the same intense, penetrating emotional reaction that it did in their adolescence (“You gotta hear this song!”) so it doesn’t hold their interest as much.

Now it seems to me the frontal cortex/limbic system balance varies from individual to individual – artists and other sensitive types seem to maintain a little more of the emotional intensity of youth, and of course some devoted listeners do stay passionate about music their whole lives through. Plenty of people strive to maintain their curiosity and sense of adventure throughout their lifetime as well — so don’t get me wrong — you’re definitely not destined to become a totally lame-o adult. But after the prefrontal cortex finishes maturing, everybody mellows out, to one degree or the other.

In some ways, this mellowing of one’s intensity seems like a real loss. People have often wondered why so many talented musicians have died from suicide or drug overdose at age 27 (the so-called Forever 27 Club). Musicians often produce some of their best songs early in their career – songs they wrote in their youth that were fueled by the emotional intensity of their adolescent brain. Twenty-seven is right around the time the frontal cortex would finish maturing. Is it possible the drop off in the intensity that once fueled their creativity and the emotion of their songwriting creates a deep despondency in artists? Maybe. Just a personal theory of mine.

But here’s the good news – not only will the completion of your brain development not make the vast majority of us suicidal, you’ll in fact experience it as a good feeling and positive change! You can actually feel it happening. There will be a time around your mid-twenties when you notice a change in yourself. You start to notice that you feel more stable, more steady, more secure. You’ll think about the drama in your life just a few years prior and wonder what you were thinking – you will feel like you’ve changed a lot since then and would now handle things much differently than you did then. When you feel this, you’ll know your prefrontal cortex has finished maturing.

The pre- and post-stages of the limbic-to-prefrontal-cortex shift in power are neither bad nor good; each has powers suited to a different stage in life. In your twenties, when you’re making big, important moves and decisions, you need emotion and intensity to spur you to study and ponder life’s big questions, and the strong motivation to take risks, venture out, and make commitments. Then, in your thirties and beyond, you need confident steadiness to overcome your counterproductive impulses and mood swings, and to build the things you launched in your twenties – to grow your business, expand your movement, head a family.

The trick is simply to take advantage of each power in the season it is given: The twenties are for launching, while the thirties are for building what you launched.

Conclusion

Today’s post highlighted some of the unique powers of the twentysomething brain — namely its propensity for deep passion, fearlessness in the face of risk, and a keen curiosity about others and the world. But what kinds of things should you channel these powers towards? Tomorrow we’ll discuss the second once-in-a-lifetime opportunity offered by the twentysomething brain — the chance to train the “builder” to whom you will be handing over the reins once the launch of your “start-up” is complete.

Read Part II: Train Your Brain for Lasting Success

_________________________

Sources:

The Defining Decade: Why Your Twenties Matter–And How to Make the Most of Them Now — one of the best books I read last year. Highly recommended for any twentysomething.

Why the Teen Brain is Drawn to Risk

The Half-Baked Teen Brain: A Hazard or a Virtue?

Beautiful Brains

Adolescents’ Risk-Taking Behavior Is Driven by Tolerance to Ambiguity

Teenage Brains Are Malleable And Vulnerable, Researchers Say

The twentysomething accomplishments in the intro were taken from the “What Other People Accomplished When They Were Your Age” generator.