Why are men (generally) more violent then women? Why are men (generally) drawn to competition and achieving status? Is the idea that masculinity means having courage and strength just a complete cultural construct or is there a biological underpinning to it?

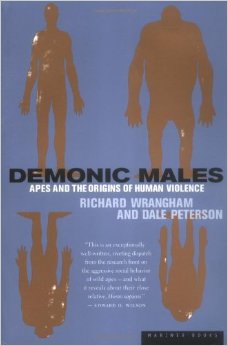

Well, our guest today makes the case that we can look to our closest animal relatives, the Great Apes, to find answers to these questions. His name is Dr. Richard Wrangham and he is a professor of biological anthropology at Harvard University. He’s also co-author of the book Demonic Males: Apes and the Origins of Human Violence. Though the title may make the book sound like an anti-male screed, it is in fact an objective exploration of the biological and anthropological roots of male violence in both primates and humans.

In today’s podcast, Dr. Wrangham and I talk about what we can learn about human masculinity from chimpanzees and other apes. We discuss what male humans have in common with male chimps and how male chimpanzee behavior can provide insights into the origins of human systems like patriarchy.

Show Highlights:

- Why chimps and humans are the only species in the animal kingdom that purposely kill (not just harm) their own kind

- What a chimpanzee murder looks like

- How male chimps band together in small gangs to kill male chimps in competing communities

- The importance of male-bonded groups in both chimps and humans

- Evolutionary theories that may explain why male chimps and male humans engage in male-bonded violence

- Why human patriarchy has a biological and evolutionary underpinning and isn’t purely a cultural construct

- What we can do with these insights from chimps

- And much more!

Demonic Males is a fascinating book and provided a lot of useful insight in my series about manhood earlier this year. I just scratched the surface of this book in my conversation with Dr. Wrangham, so if you want to delve deeper into this topic, pick up a copy.

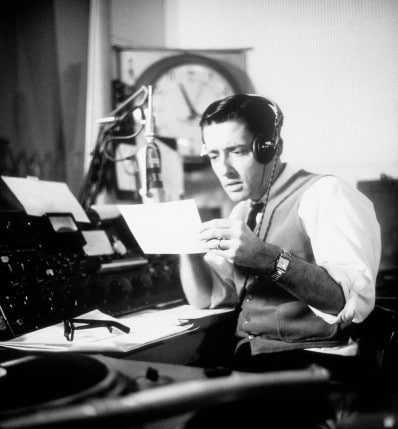

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. Now, a few months ago I wrote an in-depth series on the anthropology, the history, the philosophy, the biology of the culture of manhood that we find across the globe and across time. Yes, there are differences between culture to culture, small ones but they all have these high level general principles in common on what it means to be a man and what manhood means. And one of those high level principles that a man is supposed to be a protector and that means using violence and aggression to protect his family, his tribe and also to invade other countries to get more resources, it means being competitive, it means having martial courage, that’s what it means to be a man. We make the case that’s sort of the core of masculinity on what it means to be a man across cultures. But why is this, why is it that men are called upon to fulfill this role as protector and are expected to be aggressive and competitive and sometimes willing to do violence if necessary. Some would say that it’s just a completely a cultural construct and that if you change the culture you can change the way men behave but our guest today has an argument that there is a biological component to why men tend to be more violent, more aggressive, more competitive. His name is Dr. Richard Wrangham. He is a Professor of Biological Anthropology at Harvard University. He is the co-author of the book Demonic Males: Apes and the Origins of Human Violence.

And in his book he highlights research that has been done in recent years among primates specifically the great apes and specifically the chimpanzees on male violence and what he has found is that there are a lot of similarities specifically between male chimps and male humans on how we approach violence and how they form male bonded groups. Male chimps also are very violent and we’ll talk about how they actually engage in warfare in a way just as male humans do. Male chimps tend to form male-bonded groups like little armies, basically little gangs just like male humans tend to do. So it’s just a fascinating discussion. And we only scratched the surface in this conversation so I recommend you will pick up the book after you listen to this podcast to delve deeper into this. So without further due, let’s get on to the show with Dr. Richard Wrangham.

Dr. Wrangham, welcome to the show.

Dr. Richard Wrangham: Thank you so much, nice to be here.

Brett McKay: Well before we get to talking about your book Demonic Males, let’s talk a bit about you profession because I think it’s interesting, I’ve never heard of this before until I read your book. You are a professor of biological anthropology. Can you explain what biological anthropology is?

Dr. Richard Wrangham: Let me first explain what anthropology is and that is about just a study of people from many different perspectives but particularly understanding different cultures. And then biological anthropology is the biological component of that and to some extent it looks at differences among cultures but actually the great majority of its attention is given to thinking about us as a species in comparison to other species. So asking questions about why is it that we have different kinds of bodies, different kinds of physiology, different kinds of behavior in my case from other species.

Brett McKay: Interesting. You specifically focus on chimps, right or primates.

Dr. Richard Wrangham: Well, I started studying chimpanzees in the 1970s. When I did that I was not an anthropologist. I was just an ordinary biologist thinking about the evolution on animal behavior but it is something so striking when you study chimpanzees and after about 20 minutes of seeing them close up in the wild and just seeing the way they use their eyes and their facial expressions and their gestures you realize that there is something about chimpanzees that is sort of half-human and half-animal to put at its crudest. They have a lot of complexity in the way that their behavior and their mental process is organized and so that draws you as a biologist studying chimpanzees into the study of anthropology.

Brett McKay: Okay. So your book is called Demonic Males. This was written back in 1996 and it’s about apes and the origins of human violence. And until fairly recently scientists thought that human beings were the only species of animals that deliberately kill members of their own species in acts of warfare or murder and they often blamed our ability to reason or civilization for our violent tendencies. But that changed because of an event that happened in the 1970s where primatologists observed an incident amongst a pack of chimps that had forced them to reevaluate humanities monopoly on premeditated killing and war. Can you describe that event?

Dr. Richard Wrangham: Yes, you know you are absolutely right about the setup. Even in the late 1960s there was a very famous book called On Aggression by the great biologist Konrad Lorenz. He said humans are unique. We kill each other and other animals don’t. The thing is that people hadn’t watched animals much at that point. And there we were in 1974 with chimpanzees in the wild already realizing that there was something pretty intense going on about their relationships because we were working with two groups of chimps which had been one about five years before but they had become increasingly separate. In January 1974 a small group of chimpanzees from one of those communities moved towards the territorial border and went into the area that’s normally occupied by the neighboring group. They found one individual in the neighboring group who they stalked like as if they it was prey, as if it was lions stalking an antelope and got sufficiently close that the victim was unable to escape. He was chased down and they grabbed him and pummeled him really hard. He didn’t die on the spot. He was able to drag himself away but he died a couple of days later and that was the first case that any of the chimp people saw in which you had really deliberate hunting and killing of member of their own species, another adult of their own species and very dramatic.

Brett McKay: Yeah the way you described it just seemed really brutal because chimps are, they’re very strong and they are like three or four times stronger than human beings or something like that?

Dr. Richard Wrangham: Yeah. So I mean one of the amazing things as we have now accumulated much more information since in the last 20 years is that you can take something like a 100 kills that have been seen with real confidence in the wild and not a single case of any of the attackers being hurt. Well, that’s amazing considering that you’ve got an animal three or four times as strong as a human fighting for its life, absolutely desperate but it can’t put any wounds on the aggressor and why is that because they always choose when attacking, to choose to attack in sufficient number that they are safe. So basically if four of them each take one limb and hold it on then the fifth can do whatever they like. They can ram on the ribcage of the victim and nothing is going to happen. In fact what they do is they tear out the thorax and they tear off the testicles and they pull skin back by gripping it with their teeth to just pull it away from the body, also wound all over the place, I mean it’s a terrible stuff and yet they don’t get hurt because they have immobilized the victim and that’s because they’re smart enough to organize a group of 4-5 or 8 or 10 or 12 or whatever it is to isolate one victim and then do the worst.

Brett McKay: Okay. So, but why do chimps do this because in most species animals just defend territory but what you are describing here and what primatologists have observed countless more times since then is that these chimps are actually organizing and going into other communities and basically raiding them. What is the evolutionary purpose, I mean what do they stand to gain from that?

Dr. Richard Wrangham: It seems pretty clear what’s going on. What they stand to gain is territory, it’s more land. It’s not that they take over the neighboring group. It’s just that and if they attack members of neighboring groups and kill them then it’s more likely that they will be able to use that area in the future that it will be poorly defended by the neighboring group. So they just increase slightly the area that they use and why is that important? It’s because the bigger the area then we know this very clearly, the more food they get and the more food they get then the faster they are able to reproduce and the better they are able to survive because energy coming from food is always limiting and the more you can get then the better you can survive and reproduce.

Brett McKay: Fascinating. Are chimps the only primates that do this besides human beings, I mean do orangutans or gorillas do this sort of raiding?

Dr. Richard Wrangham: None of the other close relatives of humans do but it does look as though there is some very similar behavior in, actually a monkey that lives in the America from Mexico Zoo, Peru, the Spider Monkey because they have a rather similar pattern to chimpanzees. Instead of living in a stable troop they break up into small units like chimpanzees do. The cause of this breaking up, constant fission and fusion of the process that leave sometimes a big group and sometimes an isolated individual but you can get these great asymmetries with one group being able to isolate a lone individual. So that seems to be the key. It’s not so much that chimps are closely related to us it’s more that they have the same kind of grouping pattern.

Brett McKay: Interesting. So you talk about the chimps organize themselves in these little patrols, five or eight chimpanzees. Are these strictly male groups or are there females involved?

Dr. Richard Wrangham: No, this is very, very much male. There are occasions when females might join. The classic example is there was one particular female called Gigi who is now long dead but when she was alive in Gombe in Tanzania she did sometimes join the males. Now the funny thing about Gigi is she never had a baby. She was apparently sterilized early in life or maybe genetically sterile for some reason and anyways she was rather male like. She was rather broad shouldered and big. She did sometimes go on the patrols but even then she did not join in. She would watch the males doing all this terrible beating and attacking and she would run around excitedly. So that showed that even when a female was there it’s a male activity. And normally it is only males. And in fact, the parties, the subgroups that you find within the center of the community range of chimpanzees they are very much mixed, say 50-50 male and female but as they move towards the edge you will find the females dropping off and then by the time they get right to the edge of the territory it’s pretty much 100 percent males.

Brett McKay: Fascinating. So what similarities have you find between the way chimps engage in warfare from what we can call that, and how they bond in group and what we see in humans?

Dr. Richard Wrangham: Well, the things that are found in chimps are very much similar to what you find in humans, but humans make it more complicated of course. But the elements of group of males taking opportunity to attack helpless victims and not just attack them but kill them that is something that you see in small scale societies of humans and indeed you can say that you see in a modern on warfare you know the aim of a modern warfare, the aim of a good commander is to send his men on attack that will leave them all safe and will just kill his enemy. In other words, you are always trying to arrange for asymmetries of power to your maximum advantage.

What humans do that is more complicated is several things. I will draw attention to two of them. One is that humans take more risks. So if you look at the literature on warrior behavior in small scale societies such as hunters and gatherers what you find is that unlike chimpanzees the aggressors do sometimes get hurt. There have been ambush of the aggressors or very quick defense mounted by the defenders, they grab a weapon or whatever. And this reflects the fact that some kind of benefit is needed to compensate the warrior’s follies and the benefits are clear. The culture in the societies that of humans you have various kinds of rewards that everyone knows about, that you will get higher status, that you will get more wine, you will get access to some of the resources that are at stake. So humans are able to inculcate a militarization of a basic biological tendency.

And the second main cause is that chimps are doing this from just one particular community of up to 200 individuals who all live and share the same area. But of course what humans can do is organize the coalitions to be between neighboring villages or neighboring groups and then that tremendously enlarges the whole operation.

Brett McKay: Interesting. One of the things that this book did for me was that it kind of shadow that myth that a lot of people have about civilized cultures being the only type of culture that engage in warfare and that primitive hunter-gatherer societies live in peace and harmony but the research shows that warfare is actually very ubiquitous or was very ubiquitous amongst hunter-gatherer societies. Can you describe some of the research that shows how likely someone was to get killed in a hunter-gatherer society or how likely they were to actually kill another person because I think, yeah the society, I guess that the noble savage is the myth that people have. Where does that myth come from and why do we have that?

Dr. Richard Wrangham: Historically you can talk about it being the musings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau the 18th – 19th century French intellectual who was just very impressed by a few primitives or few small culture people that he came across, but as with many of these people they had already been affected by modern life. The basic answer to your question about why is it that we tend to think that people living as hunters and gatherers are so peaceful is that they have rarely been studied except while they are living next to militarily powerful farmers and they are smart enough to know they are not going to do well fighting against the farmers. If you look further you will find the evidence of the farmers had in the past defeated them essentially.

That critical question is what happens when you look at hunter and gatherers that have been neighbored by other hunters and gatherers who speak a different language and there are something like six culture areas around the world where you can find such cases and there you find awful violence. So as long as you look in the right areas where you don’t have the hunters and gatherers already having been dominated by a much more powerful group then you find this sort of somewhat chimpanzee-like behavior.

Brett McKay: So, I mean the question is you’re a biological anthropologist and so there must be reason why chimps and human males specifically have this violent temperament, I mean why was it that the males in both these species developed a violent temperament and what purpose did it serve?

Dr. Richard Wrangham: Well, in a tragic way it seems to benefit both the males and the females. If you think about the community of chimpanzees they are always going to be surrounded by other groups of chimpanzees. The only way they can get more access to the food that is so important for ultimately turning and producing more babies and having evolutionary success is to expand at the expense of the neighbors. And it so happens that in chimpanzees the ecology that they have evolved with is one in which it pays to live in groups but sometimes you travel alone and sometimes you travel in a bigger group which gives arise to the asymmetry. Okay, so now males and females are both interested in getting a larger group, a larger area, what I am trying to say, where they can get more resources. And this will be true with any species but only in chimpanzees or very rarely elsewhere do you have the regular asymmetry which enable killing to be favored. Why is it just the males? Well, the mothers are burdened by their young and it’s very dangerous for them to get involved in the attacks. Over evolutionary time natural selection has favored mothers who are relatively fearful of going to the edge and getting involved in these fights whereas it has favored males who relish the idea, who get very excited by the prospect of going out and beating up the neighbors and the net result is that their group does well and as a consequence they do well as well. They are able to increase the number of babies they pass on to the future generations.

Brett McKay: Human beings are not only related to chimpanzees, in recent particularly in the media they talked a lot about the bonobos as sort of this docile or peaceful close relative of ours. So the chimps and bonobos have a different culture where the chimps are more aggressive and the bonobos are more peaceful. Can you describe a little bit more in detail the difference between chimps and bonobos and why these differences emerged between the two?

Dr. Richard Wrangham: Yeah, it is totally fascinating story and we still did not understand all of it but you said that there is a different culture between them and in a sense that’s right but if you’re going to be strictly accurate it’s a different biology, it’s a different psychology. You put chimpanzees and bonobos into zoos in identical conditions and there is a complete difference in the way they behave. Now this is very, very striking because bonobos are very like chimpanzees to look at. The fact they are so similar that western scientists had seen bonobos for some time several years before they realized that they are a different species and it’s the behavior that shows it. And what is it about the behavior? It’s a number of things but most striking than anything the bonobos are as you said relatively peaceful. It does not matter whether you are talking about captive or wild, males or females, whether they’ve been fed by humans or they are in nature, whether they are talking about within the group aggression or between group aggression in all these ways chimpanzees are far more aggressive than the bonobos. So that’s the fact.

There are other things linked to this. There is more non-conceptive sexuality among the bonobos. They are famously homosexual. They are famously diverse in their sexual practices but the important thing from a biological perspective, the most important thing seems to be the reduced aggression. And now where does this come from?

Well, the one thing I think we can say about this with some confidence is that bonobos have evolved from a chimpanzee-like ancestor rather than the other way round. The reason you can say that is because of a fascinating similarity between bonobos and dogs. So this is a little bit surprising that I suddenly introduced totally different species. But here’s the formula. Wolf is to dog as chimpanzee is to bonobo. In other words dogs have evolved from wolves by reducing aggression. They’ve become domesticated and bonobos have evolved from something like chimpanzees by reducing aggression. The reason we can say this is because just as you find in all domesticated animals there are certain features that change in the skull. The skull becomes relatively small in dogs compared to wolves as the teeth become smaller the face becomes shorter and the brain becomes smaller. Well, all of these things happened in bonobos compared to chimps.

It is a fascinating story of a parallel in the wild to what we see in domesticated animals. The parallels mean that there was natural selection against aggressiveness in bonobos and they ended up being this nicer, kinder species. They’re still somewhat aggressive but enormously less so than chimps. This probably had started happening just a little less than million year ago, long after the chimpanzee-bonobo line had split off from humans about six million years ago.

And why it happened? It’s a fascinating question and I think the answer is something to do with the fact that bonobos live in stable groups unlike these constantly varying groups of chimps that give rise to the power asymmetries where aggression can be easily carried out very safely. The reason that bonobos live in more stable groups is because they have access to different kinds of foods from the chimps and the specific foods that appears really important are those that are also eaten by gorillas. Or guess what? There are no gorillas in the areas of Africa where bonobos live. They live in the areas where chimpanzees live. So chimps and gorillas compete over these certain foods and because there are gorillas that are eating them then the chimps can’t. So the gorillas were able to eat them and by the way that leads them to live in stable groups.

The foods we are talking about are meadows of edible herbs on the forest floor. So in the bonobo areas no gorillas to eat them, the bonobos do in fact eat them and when they are eating them they can stay together in stable groups just like the gorillas can. So we think that there is a deep ecological difference between these two species that has led to a difference in grouping patterns, that has led to a difference in the economics of aggression such that aggression doesn’t pay in the bonobo world and they’ve ended up self-domesticating a bit like ending up like a dog compared to a wolf.

Brett McKay: So, is it I guess resource abundance that leads to stability, I mean, is this herb pretty abundant where you don’t have to really fight for it or take a risk for it?

Dr. Richard Wrangham: That’s right. Yeah, it’s a kind of a local resource abundance, it’s the way the food is distributed that enables bonobos to take this different evolutionary path and just shows whether or not a species ends up being more or less aggressive.

Brett McKay: Okay. So let’s move on to this because I know this is really interesting, it’s about patriarchy, right. It’s a hot topic amongst social scientists and feminists and it is popularly thought that patriarchy is a complete cultural construct and it’s often unique to the western cultures. However, you highlight research in your book that not only from primatologists but also from anthropologists that patriarchy is much more ubiquitous than we formerly thought and that there is likely a biological reason for it. Can you describe the theory of where, how patriarchy has a biological underpinning?

Dr. Richard Wrangham: You know, I mean, one of the classic confusions when people are looking at somewhat related questions and appearing to disagree when actually they aren’t really. In other words, sure, patriarchy is strongly cultural in the sense that there are lots of differences among different human societies. Some are much more patriarchal, some are much less so and those differences are going to be due to culture, and not to differences in genes or anything like that. But at the same time if you look at humans compared to other species then you find that we are sort of a particular characteristic form. And that is we are a species in which overall there is a very consistent tendency for patriarchy in every society. So were there any true matriarchal societies among hunter and gatherers or anybody else? No. You don’t find it at all. People sometimes are drifting in that direction, and you find sometimes women’s houses or women being able to take important roles in communal decisions but if there is ever a clash between what the men want to do and what the women want to do then the authority always resides with the men. So in that sense every single human society is patriarchal.

By the way, this is not just some men saying this. I mean if you take, there was a book edited by two strong feminists called Women, Culture and Society in the 1980s and those endless chapters by women anthropologists and everyone agreed. There are no matriarchal societies. So this is not some fantasy of men, this is a very firm conclusion from an analysis of the political lives of people living in every different kinds of society.

Brett McKay: So we all see patriarchy not only in humans but in chimps.

Dr. Richard Wrangham: Yeah.

Brett McKay: So why is it because males both in chimps and humans are physically stronger and that they had to do this race to go you know get more territory, I mean is that the biological underpinning of patriarchy in both species?

Dr. Richard Wrangham: I mean, well it played a role but it clearly isn’t enough and here’s why we can say that. In bonobos provide a fascinating counterpoint because in bonobos the males are bigger than the females and if it was just a matter of strength then the bonobos would undoubtedly be able to dominate the females but if there are conflicts between males and females in bonobos the females routinely win. You can talk about them being sort of co-dominant in the males and the females or sometimes you can say that the females seem to be dominating the males but you never say that the males are dominating the females. So there is a case where the differences in strength are not enough to account for the difference in social behavior. And the missing piece is the motivation of individual to get together with other members of their own gender or sex in the case of bonobos and chimpanzees and form alliances.

In chimpanzees and humans, you have this very strong motivation of men to form really effective alliances that fight alongside each other. And it is quite clear that that would have paid off in evolutionary time in the context of fighting against neighboring groups. I think that is a very reasonable interpretation of the evolutionary history of patriarchy is that it stems from that tendency. It stems from essentially war. So men now are able to use the alliances that they have so readily form in the context to war to dominate life within each society whether it’s modern day America or hunter-gatherers living on the African plains. By the way you know one should recognize that patriarchy in this sense of male dominance is cultural in this sense that it depends on the relationships among men or among women at the level of communal discussion. But if you’re talking about just a man and a woman alone in their house then it’s quite wrong to think about males always being dominant. I mean in some marriages man might be dominant to a woman in other the woman might be dominant to a man. So there’s no consistency there. It’s once you get to the social and cultural area that you get the consistency but what is so striking as you said is that it occurs both in humans and in chimpanzees.

Brett McKay: Fascinating. So here’s the question, I guess you are at Harvard University, correct?

Dr. Richard Wrangham: Yes.

Brett McKay: So, I think one of your colleagues Steven Pinker wrote the Better Nature Angels of Ourselves and he makes the arguments that violence is decreasing in the world. So, I mean if violence and aggression is an evolved trait in male humans, why is it that violence is going down? Can culture tame the beast or is there something else that’s going on because we live in an environment that has resource abundance. We no longer have to be violent to gain an advantage in the world.

Dr. Richard Wrangham: That’s a big question. You say when if it’s an evolved tendency then how come it’s going down. The implication of the question is that if something has a biological component then it’s going to be fixed, but that’s an inappropriate implication and I brought it up because it’s really important for people to recognize that just because that’s an evolved tendency that doesn’t mean it’s fixed. And yes Pinker did a wonderful job in showing that everywhere you look there is a tremendous evidence of a reduction in the actual frequency of despise, violence or torture or slavery or all sorts of things that were far worse in the past in terms of violence.

So what is happening? Well one of your ideas was I would become so well supplied with the resources that we don’t need to fight. I don’t think that’s a very powerful explanation because if you look in history and if you look in animals and if you think about it theoretically, you actually expect that animals, individuals, groups of humans that have the great ability to use resources to attack their neighbors will do so. There are many examples where as you get more resources and have more power then you use it. So, merely more power for some groups is not so important, but however if you say everybody is doing better and so we are all able to put up more effective defenses well then that would seem much more reasonable. I think- I mean Pinker drew attention to, I think he had six different forces that he reckon are very important and some of those were moral you know the spread of a different kind of morality towards people of neighboring groups. Can culture tame the beast? Absolutely, it clearly is doing so.

To me the really exciting area is the development of institutions that has been going on for several hundred years. That intervened when there is a war, I mean, we are seeing it now a tremendous number of ideas and the organizations have been brought into play to try and control the violence that is going on in the Middle East. Well, a thousand years ago it would have just played itself out and people would have massacred each other without anyone intervening. So there are now much greater efforts at all levels to reduce violence wherever it appears.

Brett McKay: Okay. So, the title of your book is Demonic Males and I think some people who would read it or would get the idea that you know men are inherently flawed because they have this violent tendency and human cultures somewhat helplessly at the mercy of the male, propensity towards violence but are there reasons you know for optimism in your research and what do you hope people take away from these insights in your book?

Dr. Richard Wrangham: I think-, I am generally opposed to this who thinks that the more we understand then the better we can take advantage of our understanding and I do feel there are reasons for optimism. I think that one of the things that Demonic Males reminds us is that there are important psychological differences between men and women. I think it’s a real stimulus to help promote the notion of increasing political power for women. I think it’s just great that countries like Rwanda and some of the Scandinavian countries now got around 50% of the legislatures of the national level being composed of women. I think one can confidently expect that that will tend to lead to less aggressive policies. Among men purely I think that if we can understand that aggression is motivated by prior difference which is what much different kinds of research suggests then we are reminded that it’s really valuable to try and erode power differences to make sure that we have bounces of power at also different levels because the way natural selection and evolution work is that individuals don’t want to take risks and if we can reduce the cultural enjoinments for militarization then if we can arrange society in such a way that there are not huge imbalances of power we can expect that we will live in a much nicer world.

Brett McKay: Very interesting. Well, Dr. Wrangham, this has been a fascinating discussion. Thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Dr. Richard Wrangham: Well, thank you very much for the interview. It’s wonderful to talk to you.

Brett McKay: Our guest today was Dr. Richard Wrangham. He is a Professor of Biological Anthropology at Harvard University and the Co-Author of the book Demonic Males: Apes and the Origins of Human Violence. You can find that book on www.amazon.com.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at www.artofmanliness.com. If you enjoy the show and you are getting something out of it I would really appreciate if you go on to iTunes or Stitcher or whatever it is you use to listen to the podcast and give us a rating that will really help us out. Doesn’t matter what it is. If you think it’s five stars, five stars. If you think it’s one star, one star. That’s okay, be honest and I would really appreciate that. So until next time this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.