For the past few months, we’ve been running a series on the nature of the male status. Today we conclude the series with an installment on how one’s status drive can be harnessed and managed in the healthiest possible way. This is an ebook-length article, and is divided into several chapters.

For the last few months, we’ve been discussing the complex nature of status — an individual’s position within a group of people and how much approbation, respect, recognition, and attention he or she receives from others.

We’ve talked about the fact that status encompasses way more than wealth, and can constitute anything and everything that offers others some kind of value. It can be linked to our physical appearance, skills, fitness, intelligence, insights, creativity, personality traits, social connections, and even the ability to find and share information. Status gains and losses are thus not only felt in the size of one’s bank account, but whether or not people laugh at your jokes, compliment your appearance, like your social media posts, respond to your texts, invite you to a party, envy your cool vacation or job, admire your integrity or resilience, seek your advice, think you’ve got great taste in music or books — and in a thousand other ways.

We’ve shown that because the traits and behaviors that different groups value can vary, status is relative and context specific; you can have high status in one group, but low status in another.

We’ve demonstrated that men are more sensitive to status losses and gains than women, and that the status drive is hardly a mere cultural construct, but rather is deeply rooted in our very physiology. Status defeats and wins in fact affect nearly every system of the body, and intensely activate our neurocircuitry.

Finally, we’ve shown that while the biological root of status has remained constant, the pathways as to how status is achieved have changed over time and from culture to culture. In different periods, societies have given varying weights to various qualities and achievements. Each era’s status system has thus had its particular areas of emphasis, as well as its unique advantages and drawbacks — including our own.

In the conclusion to this series, we will lay out suggestions for how to best manage the pitfalls and benefits of the modern status system, and how one’s status drive can be harnessed and directed in the healthiest possible way. What you will find below is not so much a long blog post, but a short ebook; approach it as such. It will take about an hour to read; set aside time to read it one fell swoop, or take it chapter by chapter.

Table of Contents

- The Stoics and the Status Drive

- A 3-Pronged Approach to Dealing With Status

- Chapter 1: How to Increase Your Personal Status, or Getting As Much Status As You Can With What You’ve Got

- Chapter 2: Managing Your Status Drive in the Modern World

- Chapter 3: Helping Others With Their Status

- Conclusion

Introduction

The nature of our modern status system is both a blessing and a curse. On the plus side, there have never been so many different avenues by which a man can earn status. In primitive times, you mainly gained recognition and respect by being a great warrior and hunter. Now, you can garner status as an artist, computer programmer, social activist, tactical hobbyist, musician, vlogger, survivalist, chef, weight lifter, marathoner, etc., etc. But with all that diversity, and the fact that technology has made it possible for us to be hyper-aware of all that diversity, comes an acute anxiety. In which niche should you pursue status? If you’re a member of multiple lifestyle groups or networks, whose status judgments should you give the most weight? How do you balance and integrate all these different opinions and judgments about your worth? Is it possible to stay true to yourself, while also caring about status?

The Stoics and the Status Drive

These are some hard questions to answer. And in truth, I still don’t have completely satisfactory answers to them, even after reading about status for over a year and writing about it for the past few months.

But I take solace in the fact that these same questions have befuddled some of history’s wisest men. Across time and cultures, philosophers have grappled with the conundrum that is status. But one group who I think got closest to a beneficial working philosophy of status was the ancient Stoics.

People often have a very simplistic notion of Stoic ethics as the adoption of an unwavering indifference to all externally-rooted goods, including one’s social status. But the reality is that the Stoic worldview is much more nuanced than that.

The Stoics did seek detachment from all things outside of their complete control like wealth, health, and yes, social status, choosing instead to make inner virtue the primary focus of their lives. But the Stoics weren’t totally indifferent to those external goods, either. Rather, they thought of things like wealth, health, and social status as “preferred indifferents,” and poverty, sickness, and low status as “dispreferred indifferents.” That is, they thought wealth, health, and status were preferred over poverty, sickness, and lack of status, and could be sought as long as they did not get in the way of the pursuit of virtue. But, if they failed to attain these preferred goods, they were, well, indifferent to that outcome; they didn’t get upset about status setbacks.

To the Stoics, it was simply commonsensical to recognize that it was better to be virtuous and high status, than virtuous and low status — especially because high status people had more power and thus impact on society. Epictetus and Seneca, for example, discussed how respect and the esteem of one’s peers could be a good because it would give a Stoic philosopher the influence necessary to teach his philosophy to others. But if a Stoic philosopher happened to have the disdain of those around him, so long as he was virtuous, he did his best to not let that social rejection rankle.

Besides taking a measured approach to status, the Stoics understood that the drive for status was something natural within humans. Instead of trying to kill it, they took a more pragmatic path and guided their status drive towards more noble aims. If our natural tendency is to care about our status in relation to others, the Stoics counseled us to make sure that the people we’re comparing ourselves with shared the same virtuous aims. Not only that, they argued that we should associate with friends who are doing a better job in living in accordance with these values so that our natural drive will propel us in our own Stoic self-improvement. In short, they advised us to be selective about our status group.

But the Stoics understood that it was impossible to completely isolate oneself within one’s virtuous group of close friends. The business of life requires us to interact with those with “corrupt values.” What’s more, the Stoics believed you had a social duty to interact with these less-than-virtuous folks. But what happens when these folks scorn and think little of you? Well, then you really want to be indifferent to their opinions because they don’t share the same noble and virtuous ideals of what constitutes a respectable human being. Who cares what they think?

So the Stoics tried to strike a balance with their status drive. They preferred high status because it was in the nature of humans to do so and it came with benefits when properly directed, but they maintained Stoic tranquility if they didn’t achieve these external goods, particularly among those who didn’t share their Stoic values. They didn’t try to completely squelch our natural status drive; rather they used higher reason to get the benefits that come with seeking status, while mitigating the downsides.

And that’s the approach I’m suggesting we take to manage our status drive in the modern age.

The 3-Pronged Approach to Dealing With Status

Today, we’re seeking to strike that ever-elusive balance by laying out a Stoic-inspired, 3-pronged approach to dealing with status, updated for the modern day.

Today, we’re seeking to strike that ever-elusive balance by laying out a Stoic-inspired, 3-pronged approach to dealing with status, updated for the modern day.

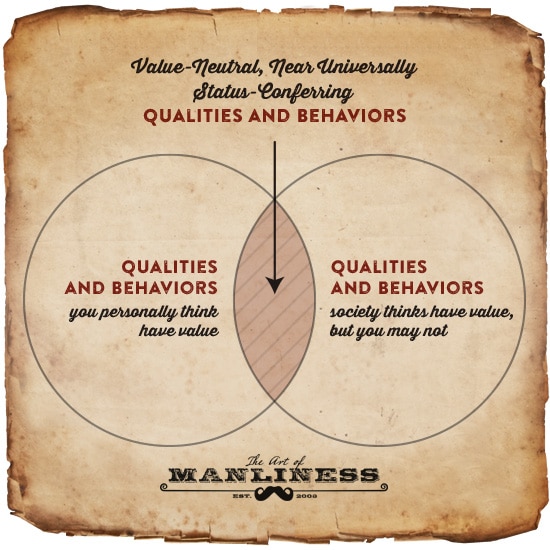

The first prong involves doing what you can to increase your own status in the category of “preferred indifferents.” While there are a diversity of values and status judgments out there today, there are still some characteristics that appeal to nearly everyone. Enhancing these characteristics will give you confidence and a sense of well-being, and set you up for success no matter what path you pursue.

With the second prong, you proactively seek to manage your status drive in a healthy way. The modern status system pulls this drive in myriad different directions, so that the status “game” can seem overwhelming and unwinnable. It’s essential to learn how to block out the cacophony of voices telling you who you should be, and direct and focus one’s status drive on virtue and the things you feel are most important.

Finally, you do what you can to look out for the status of other people. While it’s great to get one’s own status drive in harness, no man’s status exists in a vacuum. We’re all interconnected in the world of status and it’s in the interest of society, as well as simply being a virtuous thing to do, to help other people manage their own desire for status in a healthy way.

The ultimate goal of this 3-pronged approach to dealing with status is to make the most of its beneficial aspects, while mitigating its potential pitfalls.

Chapter 1: How to Increase Your Personal Status, or Getting As Much Status As You Can With What You’ve Got

In today’s world, there are many different groups that each hold up their own values and standards for status. But there is also a set of qualities and behaviors that have almost universally conferred status across time and culture. Cultivating these traits will enhance your status wherever you go and in whatever you do, and help increase your overall influence both in your chosen community and in the wider world.

These characteristics form a basic foundation of status, such that, even if you don’t end up excelling in any one particular niche, you’ll still experience the confidence and well-being that comes with being healthy, having strong social support, and feeling competent and useful. Indeed, the best thing about most of these status pursuits is that they come with major benefits outside of status itself. Status need even not be their end goal, but merely a happy by-product.

These status avenues, and the qualities attendant to successfully seeking them, are also less subject to value judgments; they’re “preferred indifferents.” As long as you don’t pursue them at the expense of virtue, they don’t require you to change your beliefs or alter your principles; they don’t require you to compromise who you are but to simply, in the words of the Greek philosopher Pindar, become who you are.

Becoming who you are doesn’t mean becoming whoever you want to be. You may have some crazy dreams that, frankly, are never going to happen, simply because of the limitations that have been placed on you by culture, biology, and even blind luck. Perhaps you’re not good looking, perhaps you grew up in a terrible family, or maybe an accident has befallen you that hinders your ability to work. Maybe because of these limitations, you’re never going to be a millionaire playboy who flies around on private jets with naked women, suitcases of cash, and lots of awesome guns. (See Dan Bilzerian.)

And you know what. That’s okay.

Because becoming who you are simply requires that you work within the limitations life has set for you. Instead of seeing these limitations as a curse, becoming who you are sees them as a blessing in disguise — an opportunity to get creative in trying to make the most of what you’ve got.

So instead of thinking of increasing your status as trying to be better than other people, think of it as striving to become your best self — doing what you can to always put your best foot forward. Follow the admonition of Teddy Roosevelt: “Do what you can, with what you have, where you are.”

There are accessible ways to increase your status in each of its main categories:

How to Improve Your Embodied Status

Your embodied status is the status you get from your physical characteristics. Tall, handsome, fit men have more status than short, unattractive, chubby men. Judgments based on embodied traits represent our most deeply ingrained status measuring stick. For thousands of years, humans largely evaluated each other based on physical characteristics, since they had the most to do with basic survival. And though the modern landscape has changed, people have a hard time turning this impulse off.

Nonetheless, this is the status category people most often push back against, as it seems to deal in the merely superficial. Shouldn’t it only matter what’s on the inside? Shouldn’t you write people off who care about what you look like on the outside?

Undoubtedly, your inner skills and traits should be of primary importance in your own sense of self-worth and the way others judge you. But people may never get to know those invisible qualities if your appearance and body language don’t initially draw them in. The rejoinder to this fact is typically to say, “Well, I don’t care about attracting such superficial people anyway.” But all people have the same visceral reaction to a person’s physical impression — some are just better than others at turning that measuring device off, and digging deeper into the people they meet. Yet even for these persistent folks, quieting their initial reaction takes intentional effort. Thus, when people purposefully force others to overlook their off-putting appearance and mannerisms in order to discover the man within, they’re essentially acting from a position of narcissism, saying, “I know your brain will have a deeply ingrained impulse to write me off, but I want you to work to overcome it anyway, because baby, I’m worth it.”

By enhancing your appearance and body language, you work with people’s basic inclinations instead of against them, making it easier for folks to want to get to know you. It’s a move that’s both self-serving and generous at the same time.

Keep in mind that embodied status signals don’t merely confer status because of their face value, but because they point to underlying traits. The goal then is simply for your “packaging” to accurately and winningly advertise the contents within. Think of your outward appearance and mannerisms as providing others a seamless doorway to your inner man.

While no one has complete control over their embodied status — you don’t have a say about the genes that made you short nor about the disfiguring accident you had as a child or even as an adult — you can influence some aspects of it. Focus on the things you can change. You may never look like Brad Pitt in Fight Club, but you can be your best self.

Below are a few suggestions you can use to improve your embodied status:

Get in shape. A fit, muscular physique sends a signal to the most primal parts of other people’s brains about your strength and ability to dominate and protect. Fitness also signals to other people that you’re disciplined and capable of enduring pain in pursuit of a goal. This is likely why men with an average-to-husky build make more money than both their skinny and obese peers. As reported by The Wall Street Journal, research has found: “Thin guys earned $8,437 less than average-weight men. But they were consistently rewarded for getting heavier, a trend that tapered off only when their weight hit the obese level. In one study, the highest pay point, on average, was reached for guys who weighed a strapping 207 pounds.”

You don’t have to have a perfectly chiseled physique or be super swole to get the status benefits that come with looking fit. In fact, both men and women often rate men with super chiseled bodies as less attractive than men with higher percentages of body fat. Instead of communicating health and vitality, extreme leanness can signal vain self-absorption. People would rather be around a man who spends his time developing skills and attributes that make him useful and add value to those around him, than one who invests all his time, attention, and willpower in managing his macros. The sweet spot then is to be fit, without being freakishly fit.

We’ve got plenty of articles on how to get in shape. Read through our Health and Sports sections for some ideas. Keep in mind that diet accounts for 80% of physique changes. If you’re overweight, start eating fewer calories in general and eliminate as many “bad” calories as you can from your diet, specifically sugar and refined carbohydrates. If you’re underweight, start eating greater amounts of good-for-you whole foods.

Whether you’re overweight or underweight, start weight training. Nothing packs on lean muscle like loading up a barbell and lifting it up and down a few times every other day. For the novice lifter, I recommend the Starting Strength program.

Wear clothes that fit you well. Even if you’ve got a rock-solid body, clothing covers about 90% of it and plays a huge role in how people perceive you. So if you’re fit, you want to wear clothes that enhance what you’ve got lying beneath, and if you’re not in great shape, you want your clothes to downplay that fact and improve your overall appearance.

That means accentuating the masculine body features that most signal status. For men, a “V”-shaped torso — broad shoulders that taper to a slim waist — telegraphs health and physical fitness. So wear clothing which enhances that silhouette. A sport jacket, which broadens and heightens your shoulders, while bringing you in at the waist, is one of the best pieces of menswear for this purpose.

With a sports coat, and anything else you wear, fit is paramount in helping you look put-together. The most general guideline for a good fit is that the fabric should sit close to your skin without pinching or constricting. You shouldn’t feel tugging when you move around, but you also shouldn’t have any loose billowing or sagging. Suits and shirts should be tailored so they taper down your waist, thus accentuating your manly torso.

If you’re overweight, but are working to get in shape, fit is even more important. People have a lot of negative assumptions about overweight men: fat, sloppy, lazy, greedy, etc. As unfair as these judgments may be, they’re the reality in our society. But with properly fitting clothing, you can blunt these undesirable status signals.

For more detailed information on style for large men, read our article on the topic.

If you’re skinnier or shorter, be sure to have your clothing tailored so that it fits you. If you’re in the vertically-challenged category, Brock over at the Modest Man is a great style resource.

Take care of basic hygiene and grooming. Keeping up with basic grooming and hygiene can go a long way in improving your embodied status. Truly. Not only does it give you the appearance of health and vitality, it also signals conscientiousness, a trait that almost everyone values.

Just do the stuff that your mom and fifth grade health teacher taught you. Shower every day, wear deodorant, brush your teeth, floss, shave, and keep your facial hair well-groomed.

If you have problems with dandruff, use an anti-dandruff shampoo. If that doesn’t work, consider visiting a dermatologist for a prescription shampoo. (This is something I had to do.)

If you’re a grown ass man and still break out with acne (me again), wash your face twice daily with a gentle cleanser and apply a benzoyl peroxide cream on the problem areas. Also, consider avoiding or at least reducing foods that contribute to breakouts like sugar, refined carbs, and caffeine.

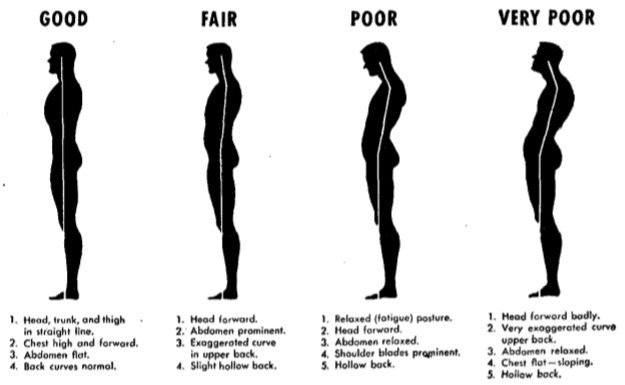

Improve your posture. Our body language does a lot to convey our status. If we think we have low status, we’ll often assume a submissive posture like slouching or looking down. If you look low status, others will think you’re low status. So stand tall with your chin up (you don’t want to throw your chin too far up though, or else you’ll start looking snooty — FDR had this problem).

For detailed info on improving your posture, see this guide.

Have a firm handshake. Your handshake is another form of embodied status. For men, firm handshakes are associated with dominance and confidence; limp handshakes with submissiveness and uncertainty. If you want to convey high status, have a firm, manly handshake. Don’t make it too firm, though. If you crush someone’s hand, you’ll just come off like a low-status douche.

Talk low, talk slow. Men who speak with lower voice pitches are perceived as having higher status than men who speak with higher pitched voices. One study found a correlation between salary and voice pitch — the deeper the voice, the higher the salary. In fact, researchers found that a 25% decrease in voice pitch was associated with a $187,000 increase in annual salary. While nature determines whether or not you’ll have a James Earl Jones baritone, there are some things you can do to deepen and improve the pitch and tone of your voice. Check out our video and article on how to develop a manly voice.

High status men also speak slower and aren’t afraid of silence in conversation. Talking fast, and rushing to fill any quiet moment makes you seem nervous and insecure. So summon your inner Sam Elliott and make an effort to slow down your speech, speaking only when you’ve got something worthwhile to say.

Look people in the eye when you talk to them. Research has shown that people who make frequent, high levels of eye contact are perceived as more dominant, high status, and personable. Low status individuals will make less eye contact and will typically be the first to avert their gaze.

So heed the advice dad gave you when you were a kid: look people in the eye when you talk to them! For the socially anxious, this can be challenging, but with practice, you’ll soon get over your fear.

But make sure you do eye contact the right way. If you try to stare holes into the back of someone’s head, you’re just going to creep them out. Be sure to read our detailed article for tips on how to make effective eye contact in life, business, and love.

How to Improve Your Ascribed Status

Ascribed status is that which you have by merit of birth (race, sex, class, etc.), belonging to particular groups of people, or assuming certain roles and leadership positions. Just like embodied status, there are parts of our ascribed status that we really don’t have much control over; if you’re a black man born on the South Side of Chicago, or a white guy raised in an old New England family, people are going to make certain assumptions about you that you can’t do anything about.

But just as with embodied status, there are some things about our ascribed status that we can influence:

Build your social network and surround yourself with quality friends. In caveman times, being able to cooperate with other men in hunting and fighting was vital for survival. Selfish, misanthropic, a-holes not only hurt themselves, but also the tribe. Those who had a knack for political and social adeptness, on the other hand, were able to build ties with others and accumulate a strong team of allies. The fact that they were the kind of men other men sought to partner up with gave them high status.

What was true thousands of years ago is true today. People make status judgments based on the size and quality of a person’s social network. If you have more friends and connections, it’s a signal that you have the relational skills others find valuable. You have status. If you don’t have a lot of friends or your professional network is small, people will usually assume there’s something off-putting about you — that you don’t get along well with others and don’t have the qualities necessary to maintain relationships.

And it’s not just quantity of people in your social network that determines ascribed status, it’s also the quality. If you hang around a bunch of losers, even if you aren’t one yourself, people are going to ascribe their qualities to you. As the old aphorism puts it: “When you lie down with dogs, you wake up with fleas.” If you hang around ambitious, smart, hardworking, tough dudes, on the other hand, people are going to assume that you’re ambitious, smart, hardworking, and tough, too.

So one thing you can do to improve your ascribed status is to 1) improve your social skills, and 2) use those social skills to increase the size and quality of your social network, with an emphasis on face-to-face connections (we’ll talk more about why later). Learn how to make small talk, avoid conversational narcissism, really listen to others, convey warmth, give and take compliments, and more. Then get out there and start getting to know more people.

If you’re like many men, you probably have few, if any, close friends. So start there. I know it sounds kind of weird, but set a goal to make at least one or two good friends that you see on a regular basis. Yes, it’s a hard thing to do when you’re a grown man, doubly so when you’re married and have kids, but it’s possible if you’re intentional and proactive about it.

While you’re working on developing those close friendships, work on developing your “weak ties” as well. Attend conferences for work or based around an interest of yours. When you get invited to a party, go. Join a sports team. Get active in your church. Network and build your metaphorical Rolodex. Not only will these weak ties provide you with social proof of your ascribed status, they can also be the source of those close friendships you’re trying to form.

For information on how to network without being skeezy about it, see our podcast on the topic.

Besides building up the size of your social network, take a look at the type of people you associate with. Seek out people who push and challenge you to be better and dump toxic people from your life.

A caveat: while you should certainly be intentional about building your social network, it’s important that your intention doesn’t turn into superficial single-mindedness. People can sense when you’re using them in a purely utilitarian matter, which makes them think less of you and greatly lowers your status. Building up your social network effectively and in a non-icky way requires you to always try to bring more value to the table than you take. More on that in a bit.

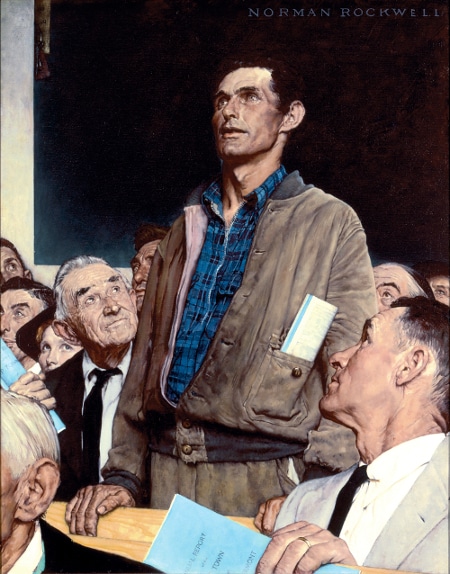

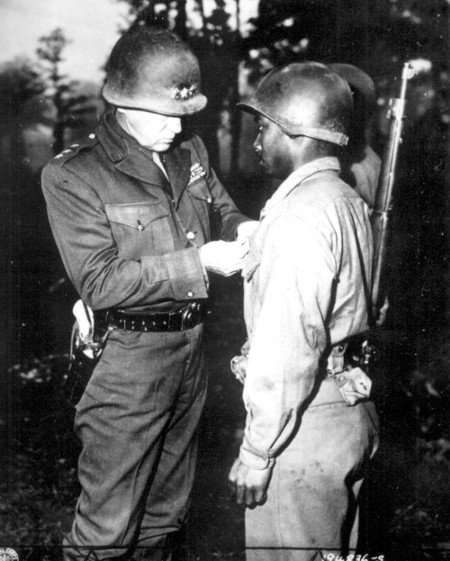

Volunteer for leadership positions. Research has shown that randomly assigning someone as a “leader” for an ad-hoc group will give that person status in the eyes of his peers. Sure, he might do something later on to lose that status (being too domineering, making poor decisions that affect the group), but simply filling the role of leader gives the person status.

With that in mind, volunteer for leadership positions at school, work, and in your community as your time and talent allow. You’d be surprised at the opportunities that are out there. Neighborhoods, clubs, churches, civic groups, and work associations rely on volunteer leaders. Is the work often thankless? Yes. But you can earn some ascribed status by taking on that responsibility, and leadership positions also provide you opportunities to increase your social network (which increases ascribed status) as well as to earn achieved status by adding value to the group through your skill and know-how.

How to Improve Your Achieved Status

Achieved status is status you earn by providing value to others through your abilities, skills, and talents.

Increasing your achieved status within any social group comes down to one thing: be useful.

Useful people are high status people, as they bring value to those around them. This value can be offered on the personal, professional, or societal level: the employee who’s able to make an impromptu presentation that wins over the client; the boyfriend who can fix his gal’s washing machine; the inventor who creates a time-saving product; the friend who can pull you out of a funk; the musician who writes a fantastically catchy song; the politician who offers a moving speech. Those who improve the lives of others in ways both big and small gain status in their eyes.

So instead of looking at what other people can do for you, look for what you can do for other people.

It’s counterintuitive, yes. We typically think of individuals with high status as demanding a-holes. While these sorts of individuals can gain and maintain status in the short-term with this domineering approach, in the long run they often lose the respect of their peers. Remember, even chimps don’t like to be bullied and will eventually revolt against an overly aggressive and domineering alpha. The research shows that long-lasting respect and status goes to the person who has talents and skills that can help their social group and, most importantly, are willing to share those talents and skills for the benefit of their peers. Status requires generosity.

What’s interesting is that low status individuals have a tendency to take the complete opposite approach to gaining status. Instead of taking steps to ingratiate themselves to those around them, low-status men are more likely to seek status by engaging in aggressive and hostile behavior. This makes sense when we take into account the status-serotonin connection we discussed in our article about the brain chemistry of status. Serotonin makes us feel calm, social, and in control. Serotonin levels increase as one gains status and decrease as one loses status. So folks who constantly encounter status failures likely have low serotonin levels, which results in hostile behavior, which only perpetuates and even deepens their low status. It’s a self-defeating cycle.

But the cycle can be broken. Research has shown that low status individuals can train themselves to shift their focus away from themselves and their low status and to start focusing on how to be useful to others. It certainly takes some discipline and humble pie, but it is possible.

With all of the above status conferers, remember that you don’t even have to seek after them from the desire for status itself, and can let status be their happy by-product. So too, remember that when it comes to these “preferred indifferents” — you do what you can to get them without letting them sidetrack you from virtue, but after you’ve done what you reasonably can, if there are places you still fall short, you face those status defeats with Stoic detachment. Control what you can control, and then let the chips falls as they may.

Become the Gentleman Barbarian: Combining Dominance and Prestige

Sociologists posit that status hierarchies can be based either on dominance or prestige. This distinction was discussed in detail in this post on “the myth of the alpha male.” Here’s the Cliff Note’s Version: in dominance hierarchies, individuals gain status through threat, intimidation, and displays of force. Basically, your stereotypical “Alpha Male” behavior. In prestige hierarchies, individuals gain status and deference by displaying skills and knowledge that help others achieve their goals.

The modern West is largely a prestige hierarchy, and there’s a tendency in our current culture to denigrate status gained through dominance. We want men to be nice and useful, but not strong and domineering. But such a view is short-sighted. There’s a place for the “barbarian virtues” (as Teddy Roosevelt called them) of dominance in a man’s life.

Even if the qualities of physical strength, courage, and boldness aren’t often celebrated in our culture, they’re still recognized and respected by everyone on a very visceral level. And the status they confer can still sometimes come into play.

When a guy at a bar starts pushing you because “you looked at him wrong,” do you think he cares about the fact that you can make a mean pasta carbonara and engage in witty small talk?

Of course not.

But in the heat of a confrontation, he will respond to those primal dominance signals that we’re hardwired to look for and that we share with other male animals. Just like chimps and wolves, human males will avoid fights if they think they’ll lose to a stronger competitor. If this chucklehead senses that you’re physically stronger than him, there’s a good chance he’ll back down. If he continues to push you and you’re able to maintain a cool head, you’re signaling that you’re not afraid, which in turn shows that you’re the dominant one in the situation. Again at this point he might retreat back to his corner while calling you a “pussy” to soothe his ego. If he does decide to escalate to violence, all your prestige status will still be of no avail. You better have the physical wherewithal to assert your dominance over him by winning the fight. Sometimes violence is the answer.

I don’t think dominance and prestige status should be an either/or proposition. There’s a place for both in a man’s life. In fact, there’s a case to be made that the ability to be dominant makes status gained through prestige all the more meaningful. As I argued in my article “You’ve Got to Be a Man Before You Can Be a Gentleman,” the respect due to a gentleman is premised on the constraint of the more rough and hard masculine attributes like strength, courage, and aggressiveness. In the absence of these hard virtues, “gentlemanly” behavior often reads as mealy — the gilding of one’s innate timidity. But when a big, strong, aggressive manly man displays that same gentlemanly behavior, we afford him more respect and esteem. We recognize that he could have just taken what he wanted by virtue of his dominance, but that he has consciously chosen to earn our respect by seeking to be useful to us. In short, he intentionally chooses prestige over dominance, and gains all the more status for it.

If you want to increase your status to the greatest extent possible, as well as enjoy the satisfaction that comes with maximizing your complete potential in both body and mind, seek to become a Gentleman Barbarian: a man who has circumscribed both the soft virtues of prestige status with the hard virtues of dominance status into a unified whole.

Chapter 2: Managing Your Status Drive in the Modern World

The traits described in Chapter 1 — physical fitness, a strong social network, usefulness — represent the near universals of status. They are the characteristics that have conferred recognition and respect for thousands of years in every culture across the world. They were assessed within a universally similar environment as well — a small, close-knit, face-to-face tribe. Within such a community, you competed for status with a few dozen men, and you absolutely knew what was expected of you if you wanted respect, as well as what constituted failure or falling behind. And your fellow tribe members would evaluate you not simply based on one status marker, but holistically. Maybe you were butt ugly, but a great hunter. Or maybe a disability prevented you from hunting, but your propensity for storytelling, humor, or diplomacy won you friends and allies. Even if your place wasn’t at the top, there was a place for you.

Today the social landscape is vastly different. Rather than small communities, we have large, fragmented networks; instead of one standard for status, we have legion. Thanks to digital technology, our geographic village has become an abstract global community and our number of status competitors has expanded exponentially. Forget surety about your place in the world; even if you’re high status in one group, you’re likely low status in another.

Yet the status-sensitive mechanics of our brains continue to operate just as they have for thousands of years: reacting with euphoria over status gains and despondency over status defeats. In today’s world, though, our status reaction is often triggered by things which don’t make sense for us to be concerned about — things that don’t have anything to do with our survival, much less our well-being. The modern man’s status drive is pulled in far more directions than our ancient ancestors’ were — directions that often do far more harm than good.

The result is a fundamental mismatch between our current social and cultural environment and what our status-sensitive brain evolved for. This mismatch is a big source of the increasing status anxiety many modern Westerners feel today. The solution then is to try as best we can to recreate the kind of environment our status drive was originally designed to navigate — a more natural habitat, so to speak.

The primary way we do that is by being very deliberate about what we decide to base the bulk of our status on, and with whom. We can’t always control the yardstick with which culture measures status, or what people think of us, but we can control what we care about, and how much weight we give to what other people think.

Below we go into detail about some brass tack tactics that you can use to balance, weigh, and manage the different status assessments you’re confronted with in the modern day. We also cover how to reap the benefits that come from our natural status drive (self-improvement, emotional and physical well-being) while not letting the burden of status anxiety become crushing.

Know What You Really Value

“In A Confession (1882)…[Tolstoy] explained how at the age of fifty-one, with the publication of War and Peace and Anna Karenina behind him, world-famous and rich, he came to realise that he had long been living his life not by his own values, or even by God’s, but by those of ‘society,’ which had inspired in him a restless desire to be stronger than others, more renowned, more important and richer. In his social circle, he noted, ‘ambition, love of power, covetousness, lasciviousness, pride, anger, and revenge were all respected.’ But now, confronting the notion of death, he doubted the validity of his previous goals.” –Alain de Botton, Status Anxiety

We live in a diverse, heterogeneous society. This means that beyond the traits outlined in Chapter 1 that nearly everyone recognizes as status-conferring, there are a plurality of values which exist that offer people a sense of status within their particular lifestyle group. Some think driving a Maserati and living in a big mansion shows status, while others believe that living frugally and simply does. Some think being a childless free-wheeling bachelor is high status, while others think being a devoted family man is. Some think being a strictly rational, secular humanist demonstrates status, while others think being a godly Christ follower is the ultimate status anyone can achieve.

If you’re not clear on what you yourself actually value, you’re likely to find your status drive pulled in many different directions; you can find yourself going after status in areas you don’t truly care about, and suffering status defeats from the criticism of those you don’t really respect. Concern for status is a two-edged sword. When it aligns with one’s values, it can help motivate you to live up to your ideals. But when it contradicts those values, it can distract you from your chosen pathway.

Thus, it’s paramount that you become crystal clear on what you think is truly valuable in life. This creates a filter that helps you gauge which status pursuits and opinions to disregard, and which to lend your attention and consideration. You must be selective!

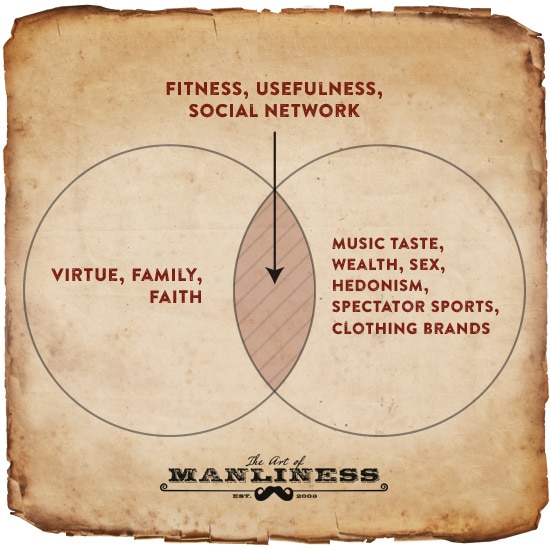

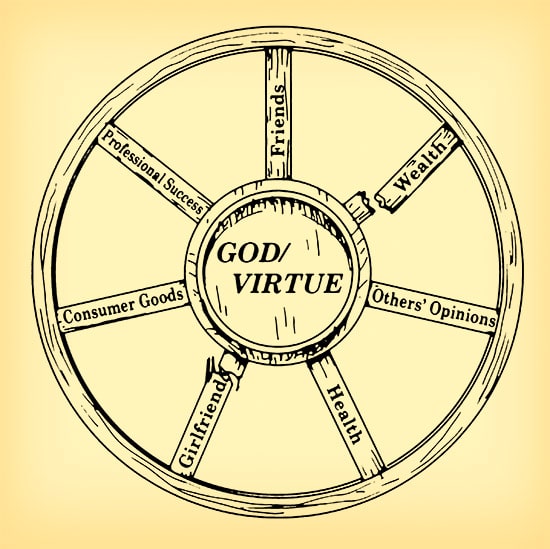

The things you might choose to care about fall into 3 categories, each of which should be lent varying degrees of your concern and attention. From most important, to least:

Virtue and other unqualified goods. The Stoics believed that virtue should be the focus of a man’s life, because it alone resides completely within our control. I’d add faith to the list of those things one can unabashedly value — caring both for how God and one’s fellow believers see you. And while the Stoics would disagree, I’d put family in this category as well. Since our family relationships are not something we can completely control, the Stoics opted for emotional detachment in this area too, arguing that one should be unmoved even by the death of a child. But sometimes the Stoics took things too far in my opinion, and the call to rob oneself of expressing the depth of genuine human feeling is one of the weaknesses of the philosophy. For a man who thinks as I do, “That no success can compensate for failure in the home,” falling short as a father or husband should rightly be allowed to sting right down to the core.

Preferred indifferents. This is the stuff we’ve already discussed in Chapter 1 like health and social connections, and also includes romantic relationships, professional success, wealth, etc. We have some, but not complete control over these aspects of our lives and we should do what we can to excel in these areas, allowing the competition-spurring properties of our status drive to motivate us to work harder and reach higher. But at the same time, you must be careful that you do not let them get in the way of your pursuit of virtue, nor invest your whole identity into them, lest you become devastated by status setbacks in these areas.

Unpreferred indifferents. Finally, there’s stuff that triggers your status drive, but offers you no real benefit, and can in fact end up distracting you from working on virtue, relationships, and other things you value more. This includes criticism from strangers online, pop culture, media, and advertising images that sell a lifestyle that contradicts your values, and enticements from friends that’ll pull you away from your chosen path.

It’s important to place virtue at the center of your identity, as it’s the only thing you have complete control over. Even if a few of of your status “spokes” fall apart, your life will keep on turning. If, on the other hand, you place something like wealth at the center of your life, and you lose it, the wheel will fall apart, and so will your life.

Learning to manage your status means sowing the cream of your energy in virtue and other things you consider unqualified goods, moderately investing in preferred indifferents, and blocking out the siren calls of unpreferred indifferents. Psychologist William James rightly noted that wisdom is “the art of knowing what to overlook.” This can hardly be truer than when it comes to status.

Here’s a silly example from my own life on the need to re-evaluate what you value and from where you draw your status. I used to be obsessed with Oklahoma Sooner football. When I was in high school and college I watched every game I could and kept up with the team religiously. Part of my identity and status was tied up with the team. Just as researchers have documented of other football fans, I experienced a surge of testosterone and serotonin whenever they won. My brain perceived the team’s victory as a status gain for myself as well.

But whenever the Sooners lost, I felt lousy and got really pissy. Their defeat was a vicarious defeat for myself too. I’m sure if you had tested my testosterone and serotonin levels right after a Sooner loss, they’d be lower than normal, just as you’d expect to find in someone experiencing lowered status.

Several years ago I got fed up with feeling like crap whenever the Sooners lost (an outcome I had no control over whatsoever), so I just stopped following the team. And you know what? It’s been years since I’ve experienced those stomach knots and anger that comes when your favorite sports team loses. Being a Sooner fan is no longer part of my identity, so I no longer base any of my status on how the team performs.

I didn’t give up caring about status altogether. I just stopped caring in this one respect, and directed more of my energy and time to building my status based on the values that are more fulfilling to me like my family, faith, and the Art of Manliness.

It was fairly easy for me to recognize that college football was not a worthwhile pursuit on which to base any of my status. But identifying the things you truly value takes some work and contemplation. If you don’t take the time to figure out the code you live by, you may end up in the shoes of someone like Tolstoy, who felt swept away into a status competition he really didn’t want to take part in. Us humans are pretty lazy. If we don’t know what we value, we’ll typically take the path of least resistance and adopt the values of everyone around us. And in today’s hyper-competitive digital status system, that usually means trying to out-experience and out-consume the other guy on social media.

Knowing what you value when it comes to your status and ignoring the stuff you don’t value is a powerful first step in managing your status drive and beating status anxiety.

What Role Should Consumer Goods Play in a Man’s Life and Status?

Material goods and accessories have played a role in signaling a man’s underlying status going back to our earliest hunter-gatherer days. For the past century such goods have become even more important in mediating social interactions; in an large, diverse, anonymous society, consumer goods allow people to quickly evaluate people’s status from afar — not only in regards to wealth, but concerning their personality, values, and membership in particular lifestyle groups.

It would be easy to deride these judgments as purely superficial, and to say that consumerism should play no role in a man’s life whatsoever. But if you’re reading this on a computer, in clothes you didn’t make yourself, that’s clearly not a tenable position. Even beyond the utilitarian properties of material goods, they function as effective relationship facilitators.

While mate selection may have been the primary and most paramount drive of primitive man, the complexity, anonymity, and diversity of modern society has made social partner selection just as important. It’s in the interest of our future prosperity and happiness to build a solid network of friends, lovers, and business partners. Teaming up with the right people — folks we gel with, who share our goals and perspectives, have the material and psychological resources we need, and will stick with and support us — can make a huge difference in our well-being and whether or not we’re able to get to where we want to go in life.

Consumer goods — from your glasses, to your clothes, to your car — signal these values, and can help us home in on such people at a glance; when we start work at a new job, visit a new church, or drop in on a party, we immediately scan the room to see who’s displaying the kind of accessories that indicate they might be “our kind of people.” Instead of having a bunch of fruitless conversations with people we don’t end up clicking with, these signals direct us towards the most promising folks to start chatting up and trying to befriend. At the same time, our signals communicate our status to others, who are equally scanning for them. Social signals, in the form of consumer goods, thus facilitate social exchange and the formation of like-minded cooperative alliances.

This isn’t to say that consumer goods should ever be a man’s primary focus. Rather they should simply serve, just like they did in primitive times, as symbols of your underlying traits and real accomplishments and actions taken. You must always consume less and create more, and if you want to signal the nature of your creativity with your clothes, do so in a modest and moderate manner.

Belong to a “Prehistoric” Social Tribe

Besides being deliberate about the things we base our status on, we should also be intentional about the group of people we compare ourselves to in order to determine our status.

Choosing what our values are does a lot of that work for us. If you decide that lifting a lot of weight is important to you, you don’t care about how much weight you lift compared to a person whose focus is primarily on running. You’re going to care about how much weight you lift compared to fellow lifters. If you’re a computer programmer, you don’t compare your skills to a technologically inept artist, but to equally skillful programmers. If you’re Catholic, you’re not going to care how you stack up in living the Cardinal virtues compared to a Buddhist. You’re going to care how you stack up compared to other Catholic men. (Someone of a theistic persuasion ultimately only cares how he’s doing in the eyes of God, but his brothers in the faith can help keep him accountable and on the right track.)

While knowing what we truly value will cause a selective sorting in whom we compare ourselves with, it’s in our interest to do what we can to further shrink and control the size of our status reference groups. As we’ve noted earlier in this series, our brain’s hardwired sociometer evolved thousands of years ago when human social groups typically didn’t get larger than Dunbar’s Number, or around 150. As groups became larger and larger, status competition increased, which caused an uptick in status anxiety.

Instead of just competing within a status niche in your geographic location, you’re now theoretically competing with millions or tens of millions of other people via social media. It’s not enough to be the best videographer in your school; you’ve got to have hundreds of thousands of subscribers on YouTube. It’s not enough to be going out on a few microadventures with your family each month; you’ve got to match the epic adventures some lifestyle guru on Instagam is having. Our prehistoric sociometer isn’t equipped to handle that much status comparison. The result is information overload, and you end up feeling that the status game is unwinnable and unmanageable. Hence the anxiety.

So we should do what we can to create a social environment for ourselves that’s better suited for our evolved status drive. This doesn’t mean you have to completely drop out of society or entirely withdraw from the hurly burly of social media. It just means you’ve got to deliberately narrow who you consider to be in your same status pool and train a focusing lens on that moderately-sized community. Here are a few suggestions on how:

Quit social media (or at least be more intentional about it). To counter the exponentially increased status anxiety that comes with social media, one solution is to simply get off of it altogether. I stopped checking my personal Facebook account years ago and it’s one of the best decisions I’ve ever made. I saved myself a lot of time, but more importantly I freed up a lot of mental bandwidth that was spent in stupid little status comparisons and battles. Admit it: you’ve Facebook creeped old high school enemies just to see if they’ve finally gotten their comeuppance. And that flame war you got into with that one guy you sat next to in college history six years ago? It was probably more about you putting him in his place in front of an audience than it was about getting at the truth. It was a status showdown.

And you don’t need to go cut the cord entirely; take a week off, or even institute a weekly tech (or just social media) Sabbath, and see how you feel. If the results seem beneficial to your well-being, take a month off. Eventually, you’ll barely even remember to check your various feeds.

If you don’t want to completely drop social media for any amount of time, at least be more intentional about it. Pare down your Facebook friends and the people you follow on Instagram to those you actually respect and interact with in real life on a regular basis. Go through your friend list and ask yourself this question with each of your contacts: If Facebook didn’t exist, would I still be communicating with this person? If the answer is no, then delete them or hide their posts from your feed. With Instagram, be wary of following celebrities and other random people you don’t know. You want to keep your status reference group small and as relevant to you as possible.

Embrace small, intimate, face-to-face communities. Status was evolved to be meditated within face-to-face communities of folks who shared your values. Online, you’re judged only by the things that can be easily displayed on social media. In a small, intimate community, on the other hand, your peers can evaluate your status based on the whole man. They can appreciate the subtle but valuable qualities you embody that are ignored by the larger society, and can’t be displayed on Instagram. They can thus buoy you up in the midst of a status defeat by reminding you that while your boss may have given you the boot, you still have value to them as a brother, husband, friend, and father.

A community of friends and family who share your values will also encourage and motivate you to live your principles more fully. They’ll keep you accountable, and let you know that you’re far more than the failure you may think yourself to be.

And beyond the personal benefits, face-to-face interactions help curb status anxiety in others. More on that in Chapter 3, so keep reading.

Seek status with your ancestors and posterity. Up until about the 20th century, individuals sought status not only from their present-day peers, but also among their long-dead ancestors and their yet-to-be-born posterity. The audience was distant in time, but close in name and genetics.

Seek status with your ancestors and posterity. Up until about the 20th century, individuals sought status not only from their present-day peers, but also among their long-dead ancestors and their yet-to-be-born posterity. The audience was distant in time, but close in name and genetics.

For example, noble families in ancient Rome displayed wax masks of their ancestors in their homes as a reminder of the legacy they had to fulfill. In ancient Japan, ancestor worship was common and families fiercely guarded scrolls with their genealogy. The goal in life was to live in a way that would bring honor to the family. In the 19th century, it was common for homes in Europe and the U.S. to prominently display a family Bible that had been passed down through the generations with names of deceased ancestors inscribed in the front. Parents and grandparents told children and grandchildren stories about the dignified lives previous generations lived, and admonished them to never act in a way that would sully their lineage.

Besides seeking status and esteem from ancestors, individuals aspired for the esteem of their posterity. Instead of hoping to be known by the present anonymous masses, one would seek to live a life that would make their great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren proud.

But in the modern day, we’ve largely lost that attitude towards past and future generations. As historian Leo Braudy notes in The Frenzy of Renown, “few of those who aspire to fame [or status] in the 20th century speak of posterity.” The reason is two-fold: First, the expansion of immediate communication encourages a status of the present moment. You want as many people talking about you now as possible. Second, the increasing individualism of the 20th century pushed family ties as a source of personal identity out of the psyches of Westerners. Identity today, particularly in America, is something you fashion yourself from scratch. If you need to, you’ll cast off your family history if it gets in the way of the story you’re creating about yourself. Without a sense of history or pride in one’s ancestors, aspiring for the validation of one’s posterity has little meaning.

But I think we’d be well-served to resurrect our family — past, present, and future — as a status reference group. If we only care about our status in relation to people we connect with our identity, what’s more connected to that than our DNA?

And in fact, research suggests that when we have an intimate knowledge about our family history, we feel more self-confident compared to individuals who don’t. There’s something about understanding your past and knowing you belong to something bigger than yourself that instills confidence and motivates you to be your best.

So do your genealogy. Find out about the people who came before you and helped shape who you are today. Ask yourself if they’d be proud of you and whether or not you’re adding on to the legacy they left behind. And then think about your posterity. Are you living a life your descendants will look back on with pride? Will you inspire your grandchildren or great-grandchildren with your character and integrity?

Compare Status in a Healthier and More Effective Way

One solution to status anxiety that’s often proposed is to only compete with yourself. Instead of trying to do better than others around you, focus on doing better than you were yesterday. This is a valuable approach, and one that I at least partly ascribe to. For the most part, I try to outdo myself each and every day instead of obsessing about how I’m stacking up to others.

But competing against ourselves will only take us so far. It’s easy to get complacent when you’re just trying to beat the man in the mirror because ego and status aren’t at risk. We need the friction that comes with opposing forces to keep us sharp. When there’s a risk of public defeat or victory, we push ourselves out of our comfort zone. Other competitors can reveal flaws and weaknesses in ourselves we didn’t know we had. Competition keeps us hungry and humble. In this way, our natural drive for status can propel us to personal improvement.

But there’s a healthy and unhealthy way to approach comparison and competition. Research shows upward comparisons to others can spur self-improvement so long as the status of the person we’re comparing ourselves with is attainable.

Studies have shown that college students who compare themselves to and compete with a peer who’s doing slightly better than them do in fact increase academic performance. However, students who compare themselves to peers who far excel them academically become depressed, and their academic performance suffers.

Researchers believe the student who is doing only slightly better can provide more useful information on how a lower performing student can improve because the two are more alike than different. According to Susan Fiske, author of Envy Up, Scorn Down, students who are too far ahead aren’t able to provide a lower performing student with a useful road map that’ll guide them from where they are to where they want to be.

So when you compete with and compare yourself to others, do so with people who are doing slightly better than you. First, these peers have more to teach you on how to improve than peers that far excel you. For example, if you’re just starting out in weight training, comparing yourself to someone who’s been at it for a few months and is around your bodyweight, would be more useful than comparing yourself to a seasoned 275-pound guy who’s deadlifting 600 pounds. The advanced lifter is likely on a training program not suitable for beginners, so doing what he does wouldn’t help you.

Second, limiting your comparison group to individuals who are just slightly better than you reduces the debilitating feelings of inadequacy that can arise when you compare yourself to someone who’s majorly outpaced you. For example, if you’ve just started a business, comparing yourself to a company that’s been around for years and has millions in revenue coming in will just beget frustration. Sure, that successful business is something to aspire towards, but understand it may take years to reach that same level.

Again, be deliberate about your status reference group!

Correct the Faulty Assumptions That Come With Status Defeats

So we’re controlling our status values and status groups as much as we can; improving where we can, but not sweating it too much if and when we fall short. Another way in which we can manage our status anxiety is to correct the often faulty assumptions that we make in regards to our status failures.

There’s a tendency for us to globalize our status defeat in one area of our life to the entirety of our being. This type of thinking is what psychologists call “Me-Always-Everything” (MAE) thinking. According to the authors of The Resilience Factor, “A Me, Always, Everything person automatically, reflexively believes he caused the problem [or status defeat] (me), that it’s lasting and unchangeable (always), and that it will undermine all aspects of his life (everything).”

Understanding our tendency to make general and overarching conclusions about a status defeat can do a lot to stave off the anxiety that inevitably comes with it.

For example, let’s consider a major status defeat for many men: getting rejected by women.

Rejection hurts, badly. This feeling is intensified when your brain starts turning to MAE thinking. To blunt the sting of romantic rejection, you simply need to challenge the often faulty assumptions your brain makes about how far your failure really extends.

Here’s an example of MAE thinking that can happen when a guy gets turned down by a gal, and how he can challenge the erroneous, all-encompassing connections that the brain tends to make:

Me: “Man, Jill said no when I asked her out. I must be unattractive and awkward.” (The reason that Jill said no could be due to a whole bunch of factors that have nothing to do with you personally. Maybe she said no because she really did have something going on the night you asked her out. Maybe she said no not because you’re unattractive and awkward, but you simply don’t match up with her taste in men. Maybe you’re blonde and she digs brown hair. Or maybe she doesn’t get your sense of humor. It’s not about you specifically. If it was another blonde guy with a dry sense of humor that asked her out, she probably would have said no to him, too.)

Always: “Women always say ‘no’ when I ask them out. I’ll never have a girlfriend.” (Is this really true? You did have that date with that one gal a few months ago. Sure, it didn’t go anywhere, but she did say “yes” to you. Also, concluding that you’ll never have a girlfriend based on a single instance makes no logical sense. You might not have a girlfriend now, but you could have one in a few months. Who knows?)

Everything: “I’m such a loser.” (You’re a loser just because a single woman turned you down? That’s probably not true. You live virtuously. You have a good job and are excelling at it. You’ve got a few close friends that are with you through thick and thin. You have a hobby that you really enjoy. You have a roof over your head. Etc., etc. Don’t globalize a status defeat in one area of your life to the entirety of your existence.)

Anytime you start feeling the angst of status anxiety, check to see if you’re taking part in MAE thinking. If you are, challenge the assumptions that you’re making about yourself and others. Just because you or someone else has experienced a status setback in one area, doesn’t mean either you or he don’t have worth and value in other areas.

So too, status defeat is not even always your fault. Being good merit-o-cratics that we are, we have a tendency to attribute all the success a person enjoys solely to their own efforts. But we forget the role chance and luck play in success or failure. As the French philosopher Montaigne noted: “I have often seen chance marching ahead of merit, and often outstripping merit by a long chalk.”

Yes, some people work hard to achieve their success (and some people don’t). Even the folks who pulled themselves up by their bootstraps likely had some help from Lady Luck along the way. This isn’t to degenerate what they’ve done, it’s simply recognizing reality. So if you don’t feel like you’re as successful as one of your peers, don’t necessarily get down about it. Your failure isn’t entirely your fault, just as their success isn’t entirely their responsibility. Sometimes chance steps in and tilts things one way or another for no reason whatsoever.

To reduce the anxiety that chance’s fickle ways have on you, you simply have to do all you can to up your chances of success, and then learn not only to accept, but even love and embrace your fate. As Nietzsche advises: Amor fati.

Chapter 3: Helping Others With Their Status

“The rewards…in this life are esteem and admiration of others — the punishments are neglect and contempt…The desire of the esteem of others is as real a want of nature as hunger — and the neglect and contempt of the world as severe a pain as the gout or stone.” –John Adams

So we’ve taken steps to improve and manage our own status. We could stop there and call it a day, but I think it’s in our own interest and in that of society’s as a whole that we take steps to help others navigate the turbulent waters of the modern status system too. We’re truly all in this thing together, and an awful lot of people are really struggling these days.

Suicide and depression rates are up, and modern Westerners seem to be more miserable than ever. There are a lot of factors contributing to this growing malaise: poor diet and exercise, stagnant wages, social isolation, increasing levels of perceived stress, etc. But the anxiety-inducing nature of our modern status system is surely also to blame.

Digital technology has made stellar success — the life of our dreams — seem within reach as never before, and the carefully curated images we see on social media have sent our expectations soaring. And yet the friction of reality — the inherent difficulty in attaining all of our lofty goals — remains frustratingly the same. The collision of high hopes with the wall of actuality can result in crushing disappointment.

At the same time, we’re more isolated than ever. We lack close relationships with friends and family — a community that reminds us that even if we fail to create the next million-dollar app, haven’t found our dream girl, or got fired from the job we moved across the country to take, they still see plenty of worth and value in us. The young, especially, need mentors who can point them away from ultimately empty status pursuits, and towards more fruitful and fulfilling ones.

Alone, and buried under an avalanche of different status standards, anxiety, anger, and depression can become acute. Maybe we’ve got the mental tools and social support to keep this restlessness at bay, but a lot of folks do not.

So why not lend a hand to these fellow travelers? With the recognition that some people are really struggling, comes the recognition that our actions have an effect on others. If there’s something we can do to help people understand their worth and alleviate their status anxiety, then I think we should do it. Here are a few ideas on how:

Encourage face-to-face community. As we’ve discussed, face-to-face community allows us to manage our status drive in a much easier and healthier way. Friends and family know our complete selves, so that one narrow aspect of our status isn’t given undue weight, and all the little things we do to add value to the world are noticed and appreciated.

Unfortunately, our current culture doesn’t encourage intimate communities. In fact, it moves us in the complete opposite direction. A lot of people out there are craving more face-to-face interaction, but they either have a hard time taking the steps to get it or simply don’t know where to find it. So they resign themselves to another Saturday night surfing reddit, wishing someone would reach out to them and get something going.

If someone has to take the initiative to build greater community, why don’t you do it? It’s not hard. Don’t know your neighbors? Make small talk. Invite them over to watch a game. Start hosting a regular poker night. Part of a group of couples at church that have an affinity for each other, but can’t seem to move these friendships outside of Sunday? Be the one who invites them over for a potluck dinner party. Belong to a gym? Encourage the owners to host events that get members together outside of their workouts. That’s how communities are built: one face-to-face interaction at a time.

In working to forge a community, not only do you benefit from the social interaction yourself, but you’ll also see the results in the lives of those around you. So many people are incredibly lonely; they think everyone else has friends, but the reality is that “everyone else” is just as lonely as they are. You have no idea how much you can improve someone’s life by creating an environment where they can interact with other people on a regular basis.

For more about embracing face-to-face communication, be sure to read our article on the topic, as well as listen our podcasts with Sherry Turkle and Susan Pinker.

Embrace republican modesty. Back in the early days of America, the Founding Fathers and other thinkers believed that in order for the new republic to survive, its citizens had to develop certain qualities of character. Called “republican virtues,” these cultural principles centered on avoiding decadence, corruption, and greed, and included modesty in lifestyle and deportment. The Founding Fathers believed that once citizens began elevating themselves above others through ostentatious consumption, it wouldn’t be long before other republican virtues like frugality and self-sacrifice disappeared too. And if those went, amen to the great American Experiment.

While many of the Founding Fathers were wealthy, they lived rather plainly. John Adams was the paragon of this kind of republican modesty. Despite being a very successful lawyer, he wore homemade clothes and ate food he harvested from his own garden. He felt it was his duty not to set himself too far apart from his fellow citizens so he could be an example of solid character and an effective leader.

Today we live in a culture that has eschewed republican modesty. Instead, an ethos of crass self-promotion prevails. If you’ve got it, flaunt it. Unless you build up your “personal brand,” you’ll never get the career or life you’ve been vision boarding-ing about. (Or so they say.)

But I think we’d be well served by bringing a bit of republican modesty back into our culture. It would certainly help reduce the status arms race that takes place online, as well as the amount of aggregate FOMO in the world.

I’m not suggesting you don’t buy expensive stuff or go on nice trips that are within your means just so you don’t make other people feel bad. Just be a bit more conscientious about broadcasting your possessions and experiences to the world. Think about why you’re posting a picture: Do you simply want to show your friends what you’ve been up to, or are you really looking to make them feel jealous? Think too about whether a picture accurately reflects the reality it’s supposedly depicting: Did you take a trip where it rained the whole time, and you stayed in a crappy hotel, and your kids were nuts, and everyone was miserable, but you managed to get this one nice shot during the 5 minutes of sunshine and smiles? Did you camp next to big parking lot, but if you angled your camera jussst right, you could make it look like you were out in the pristine wilderness? Be modest and honest and choose not to post such images. Decide not to play a part in contributing to people’s artificially inflated expectations for life just so you can feel awesome and your friends can feel bad.

I know it flies in the face of our me-first, winner-take-all culture to avoid self-promotion that’s within your perfect right to engage in, and which you could easily get away with. But we can all play a part in decreasing the amount of status anxiety in the world and increasing our fellow travelers’ sense of well-being.

Be polite. Have you ever wondered why you feel so good when people use good manners around you? If you stop and think about it, the things we call “good manners” are, at their core, gestures of deference — signals of your respect for someone’s status as a fellow human being. Instead of just taking what you want like a dominant a-hole, you say “please.” Instead of just barging past people to get into the building, you open the door for them. You put others first. You submit.

Submission is a dirty word, I know, but it doesn’t have to be if you submit in an unforced and controlled way — making a deliberate decision to temporarily step down in service of what you feel is the greater good.

When people are on the receiving end of these submissive gestures, their brains get a feel-good serotonin shot that comes with the perception of elevated status. Conversely, when someone is treated rudely, their brain registers a lowered status, which decreases their serotonin production and increases their stress-inducing cortisol.

So an easy way you can give others a feel-good status boost is to just be polite. Say “please” and “thank you.” Open doors. Respond to emails, phone calls, and text messages in a timely manner. You get the idea. Etiquette doesn’t take much effort and you can do it multiple times a day, every day.

Be generous with your compliments. Another “submissive” way to boost someone’s status is to offer him a compliment. We’re often stingy with our compliments because we feel like admitting we admire someone else makes us somehow less than. But status doesn’t have to be a zero-sum game. So someone excels you in one area; you likely excel them in another. So let them know where they’re doing awesome.

Especially try to offer compliments on things that often go unrecognized by the wider world, and that folks may never have thought of as things that enhance their value. “Your lack of cynicism is so refreshing.” “Your unwavering integrity motivates me to be a better man.” “I wish I was as patient with my kids as you are with yours.” “I’ve never met anyone as unselfish and loyal as you are.” “Thank you for always being sincerely interested in my point of view.”

Compliments can lift someone’s spirits, helping them to keep on keeping on when they’re struggling through a status defeat; indeed, they’ll likely remember your encouragement their whole life through.

Express gratitude freely. Related to giving more compliments, regularly and unabashedly expressing your gratitude to others is yet another way to demonstrate healthy, status-boosting “submission.” You let people know they helped you — that you needed something they were able to give. Thanking people for what they do and who they are is such an easy way to help them recognize their worth.

“The poor man’s conscience is clear; yet he is ashamed…He feels himself out of the sight of others, groping in the dark. Mankind takes no notice of him. He rambles and wanders unheeded. In the midst of a crowd, at church, in the market…he is in as much obscurity as he would be in a garret or a cellar. He is not disapproved, censured, or reproached; he is only not seen…To be wholly overlooked, and to know it, are intolerable.” –John Adams

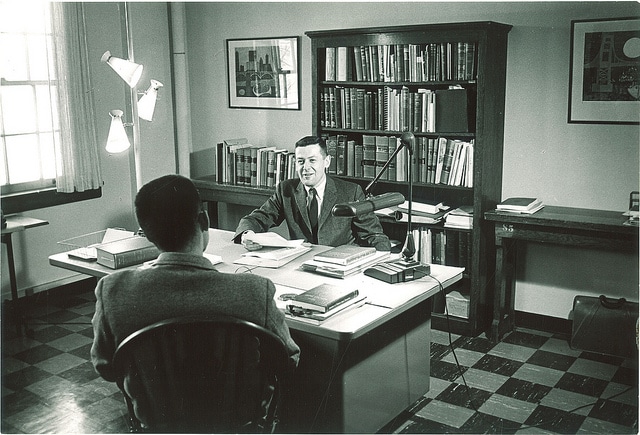

Reach out to young men who may need extra attention. There are certain segments of the population who are especially susceptible to the downsides of low status: the poor, the elderly, the disabled, and the mentally ill, just to name a few. Often these segments of the population are at best ignored, at worst ridiculed. But even simply being overlooked can induce some serious status defeat. We should make an effort to reach out to these folks so they can enjoy the status benefits that come with being recognized and reminded of their humanity.

This being the Art of Manliness, I want to focus on one segment of the population in particular that could use some extra attention when it comes to their status drive: young men.

As we’ve discussed throughout this series, men generally have a higher status drive than women. The status drive starts kicking into full gear in boys when testosterone begins surging during puberty. When properly channeled, this drive is healthy and should be encouraged — it motivates young men to strike out on their own and make something of themselves. Unfortunately, in today’s society many young men are left without guidance on how to direct their naturally increasing status drive in positive and constructive ways. Their dad isn’t around, they don’t have an honor platoon of good male friends, and they don’t belong to a real community that sees and recognizes them. Lacking mentors, they drift into some not-so-healthy paths.

Some young men scratch their itch for status in street gangs. There’s a reason why the average age of men involved in gun violence is 18-24. Their fellow gang members give them the recognition and sense of belonging — the status — they crave. And when they pull the trigger themselves, it’s usually justified on the grounds of avenging an episode where they felt disrespected — an attempt to turn a status defeat into a victory.

Other young men, lacking a positive and realistic status ideal, will look online and in the popular culture for a model of the kind of life to pursue. Plenty of lifestyle and seduction gurus hold out an incredible vision of making passive income, traveling the world, and sleeping with as many perfect 10s as one’s heart desires. The world is your oyster — all you’ve got to do is take this course, try these moves, and let go of whatever’s been keeping you in your pedestrian lifestyle. Isolated, stuck in an echo chamber of their own thoughts and desires, without mentors to keep them grounded, young men’s expectations for their own status, of the status they deserve, artificially inflate.

When the lifestyle they desire proves far more difficult to attain than they supposed, frustration, anger, and resentment build. And these feelings go unchecked, because again, they’re isolated and lacking in the guidance of friends and mentors.

In the face of what they perceive as an unwinnable status contest, these young men feel they’ve gotten a raw deal. Some come to believe that if status isn’t going to drop into their laps, they’ll demand it by force and take drastic measures to win attention.

If you look at the string of mass shootings America has experienced since Columbine, the underlying factor amongst an overwhelming number of the perpetrators is that they were highly isolated young men who perceived themselves as having an unfairly low status. The diary of one of the Columbine gunmen was filled with self-loathing rants about how he didn’t get the respect he thought he deserved from his peers (and women). We saw the same thing in the angry video manifestos of both the Virginia Tech and Santa Barbara mass-shooters. The Germanwings pilot who crashed his commercial airliner into a mountain wanted the world to know his name.