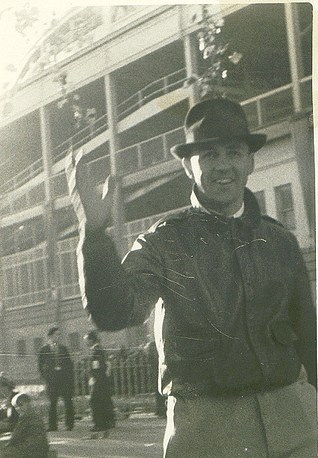

Before my great-grandfather, William M. Hurst, died, he self-published a short memoir of his life entitled Thinking Back. When I first read through it, I enjoyed hearing about his experiences growing up in Utah at the turn of the 20th century, working as a ranger for the U.S. Forest Service for nearly 40 years, raising three children, and even memories of watching Rocky Marciano in the ring. But what really stood out to me, was how my great-grandfather chose to end his memoirs — with a poem called “The Indispensable Man” by Saxon White Kessinger:

Sometime when you’re feeling important;

Sometime when your ego’s in bloom;

Sometime when you take it for granted,

You’re the best qualified in the room:

Sometime when you feel that your going,

Would leave an unfillable hole,

Just follow these simple instructions,

And see how they humble your soul.Take a bucket and fill it with water,

Put your hand in it up to the wrist,

Pull it out and the hole that’s remaining,

Is a measure of how much you’ll be missed.

You can splash all you wish when you enter,

You may stir up the water galore,

But stop, and you’ll find that in no time,

It looks quite the same as before.The moral of this quaint example,

Is to do just the best that you can,

Be proud of yourself but remember,

There’s no indispensable man.

Memoirs are all about me, myself, and I — what someone did, who they were, why their life had significance. But here my great-grandfather decided to close the account of his life by essentially saying, “Sure, I did all this, but in the end, I wasn’t so important.”

It struck me, as other nuggets discovered in old books sometimes do, as a memento from a bygone age of humility. A visceral reminder of a lost ethos.

This feeling was only compounded when I learned that Dwight D. Eisenhower — five-star general, Supreme Allied Commander, U.S. President — carried a copy of the same poem in his pocket. In fact, when Ike returned to Normandy for the 20th anniversary of D-Day and was asked to give a speech at a dinner commemorating the invasion, rather than use the occasion to wax poetic about his role in executing one of the most monumental military operations in history, this man of singular eminence instead used the opportunity to read — “The Indispensable Man.”

Today, we are apt to feel that the poem is overly deprecating. Don’t we all have unique value, something special to do here on earth? I don’t think, however, that it negates this idea. There are indeed things that each of us can do, that no one else can do; we can each make a difference, leave a legacy. When we go the way of all the earth, nearly all of us will be missed somehow, by somebody. The poem is not saying you can’t be irreplaceable, just that no one is truly indispensable. That is, on a day-to-day level, if you quit your job, someone else — no matter how well you did your work — is going to be able to take your place, and the company will keep on running. On a more macro level, when you die, the world will keep on spinning; society will keep on running; people will continue to wake up, go to school, go to their jobs, eat dinner, go to sleep. Nearly everything will continue functioning just as before. As an old saying puts it, “Graveyards are full of people the world could not do without.”

That might all seem mighty depressing, but it’s actually rather liberating. Too many people say yes to things they don’t want to do, and stay in unhappy relationships or jobs or volunteer positions out of guilt, out of fear, out of the ultimately egoistical worry that that others will simply not be able to function without them. It reminds me of this satirical headline from The Onion: “Man Leaving Company Unsure How to Break It to Coworkers Who Don’t Really Care Whether He Lives or Dies.”

The world is usually not quite so indifferent to us as that, but the truth remains that it can still get along just fine without us. Take your hand out of the bucket and the water flows back in. It’s a humbling check to the ego, to be sure, but a healthy, freeing one at that.

As Eisenhower replied to a reporter who asked whether the prevailing “view that you are indispensable to a party victory” would influence Ike’s decision to run for a second term as president:

“Did you ever think of what a fate civilization would suffer if there were such a thing as an indispensable man? When he went the way of all the flesh, what would happen? It would be a calamity, wouldn’t it?

I don’t think we need to fear that.”