Editor’s note: The following excerpt — “Practice, and Some Other Things, Make Perfect” — comes from Increasing Personal Efficiency (1925) by Donald A. Laird. Some re-formatting and condensation have been applied to the original chapter.

Back in the third grade I filled a page of the copy book with the sentence, “Practice makes perfect.” I wrote this particular line twenty-five times; I imagine that altogether I had practice in writing not less than a hundred thousand similar lines before the series of writing books were completed.

That should have been enough practice to have made my writing perfect, but it did not, for the simple reason that practice alone does not make perfect. Practice is only one way – and a very ineffective way at that – of gaining skill, or making perfect.

And what are skills? All animals enter upon life with scores of actions that are entirely unlearned. One does not have to learn to sneeze or to laugh. Just try sneezing when you do not feel like it and see how unsuccessful you are; try laughing when you do not feel like it. It has been estimated that probably 80 percent of the activities of man are of this unlearned type.

The remaining 20 percent of the behavior of man is that which determines his position in industry and life. Even though it may comprise no more than one-fifth of his daily behavior, it is by far the most important fifth when one looks to increasing personal efficiency. This one-fifth is the skills.

The moth does not learn to avoid the flame when its wings are singed once, twice, or a dozen times. Our old friend, the cockroach, is not made perfect through practice. It has been found that he can be taught tricks which he will remember for half an hour, but no longer. But men can modify their skills and become more skilled.

Work to Rest Ratio

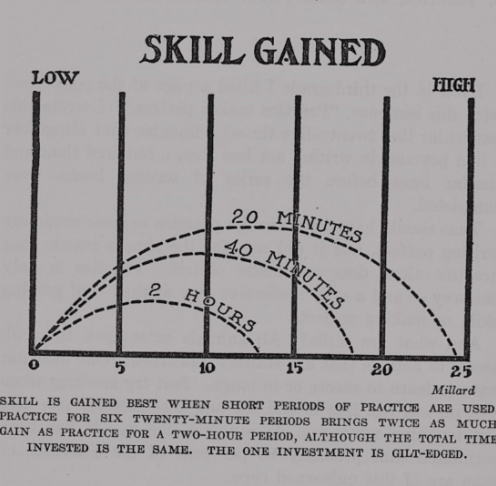

Practice does have something to do with gaining skill, but its value depends largely upon how long one practices. The lazy man’s way has been found to be the best way. Distribute your practice over many short periods; do not practice for a few very long periods. The individual who practices a music lesson for half an hour in the morning and again for half an hour in the afternoon will make more progress than the one who practices for an hour at a time once a day.

When you are learning to drive a car, to typewrite, to play some game of skill, or are memorizing, practice for a short while on many days. You will thus make much better progress. When long periods are used their principal benefit is in furnishing drudgery, and they hamper progress in becoming skilled rather than helping it.

At the time of the Spanish-American War a large concern found itself in great need of moving hundreds of tons of pig iron. The pigs were carried by unskilled laborers, at the rate of about seventeen tons a day.

An efficiency expert came along and told the laborers they were working too hard. He suggested that they work easier, rest more, and increase their efficiency with less fatigue. So the foreman blew a whistle at the end of twelve minutes’ work, whereupon the laborers laid down their loads of iron and rested for three minutes, when the foreman blew the whistle again as a signal to resume work.

The laborers now spent one-fifth of the time resting. But by doing so they were able to carry forty-five tons a day rather than fifteen tons; their hours were reduced and their pay increased two-thirds.

By proper rest they had almost tripled their efficiency. By properly spaced rest periods anyone can greatly increase his efficiency. People folding handkerchiefs who work five minutes and then rest one minute do more than those who work steadily. The mental worker who sticks close to this work half an hour and then walks around or, better yet, relaxes in his chair and gazes idly out of the window for three minutes, can do more than by working steadily by the half day. And he will be less fatigued at the end of the day.

Do not make your rest intervals too long; that is a waste of time. Do not make them too short; that does not allow greatest efficiency. Experiment with your work until you have found the best ratio of work to rest throughout the day.

Do Learning

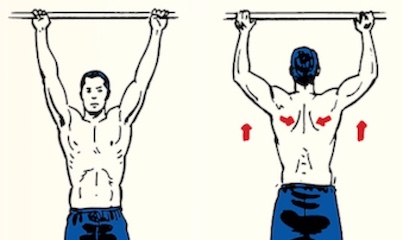

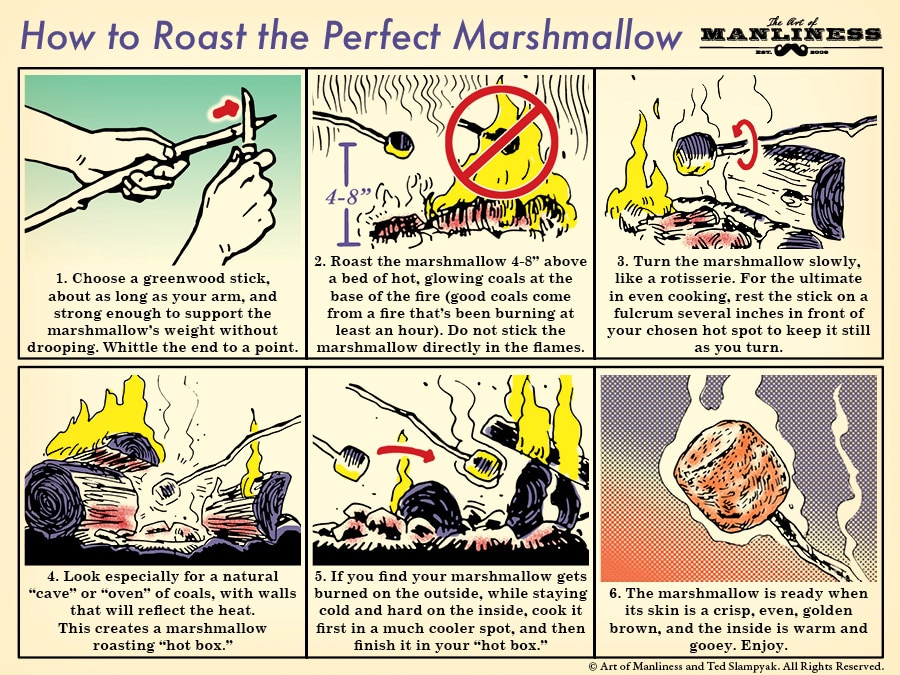

You will acquire skills better if you are active rather than if you are in a position to have someone tell you how to do it. Watching someone while he does what you want to do is a slight aid. You must do it. You will learn to drive a car much quicker by shifting gears from the start instead of having some well-meaning instructor put your hands through the movements.

Doing is essential for learning. The doer is the learner. If you really want to increase your mental efficiency, do things, do not just read about them. Put them to work at the first opportunity.

Push Past Plateaus

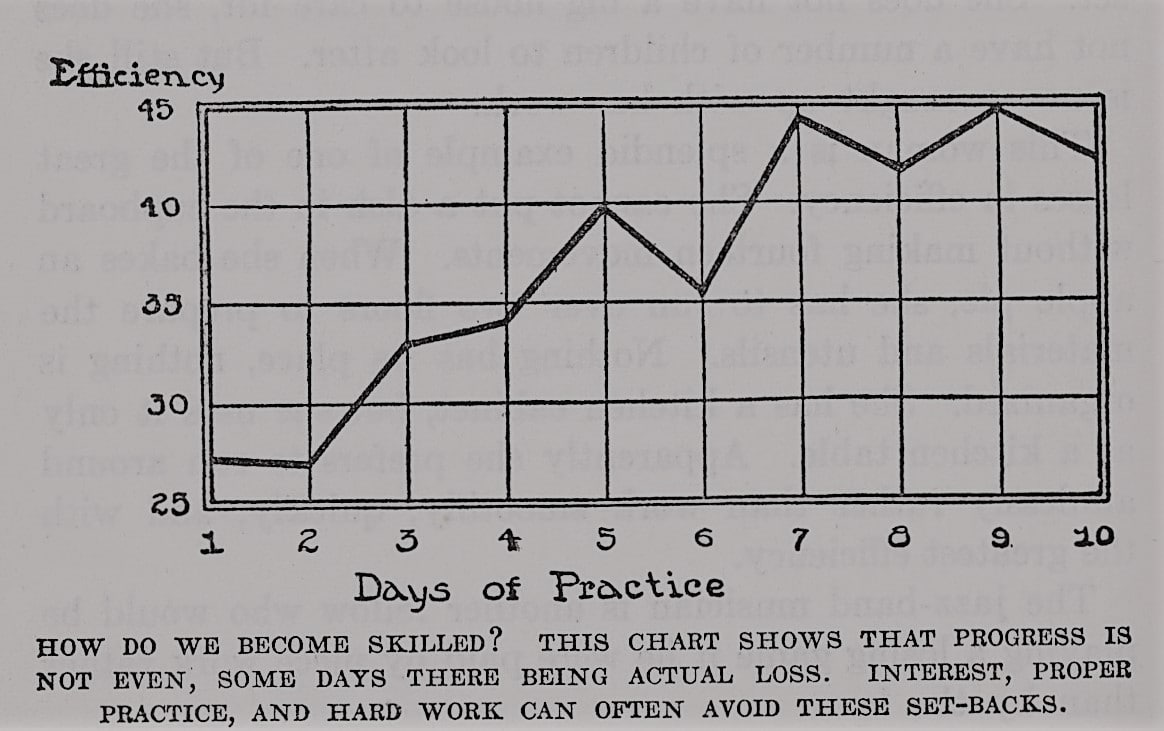

Sometimes, after long periods of practice, there is a marked loss of skill. This is a rather discouraging situation. Some days, progress is rapid; on others, it is just dragging along. There may be an actual loss at certain times.

These periods of no progress are called plateaus, because the chart of accomplishment is flat like a plateau during this period. These plateaus of despond and discouragement are common to all. They may be caused by a temporary slump in interest, or – strange as it may seem – too frequent practice may cause this stalling of progress.

These plateaus are not inevitable. Experimental work has shown that, where one bends his best efforts to overcome this period of no progress, the plateau of despond has given way to progress. Look upon the plateau as a challenge to work all the harder!

A close relative to the plateau is the decreased rate of improvement as the higher levels of skill are neared. The progress is much more rapid and spectacular early in the game, but the finishing touches of the expert are gained after practice which is long and perhaps tedious.

So do not stop because you are slowing up – there is much skill in doing and thinking for you to gain.

Train for the Job

Such a thing as general training is largely a myth.

Mathematics and some other school subjects used to be taught, not because of any practical value they might have, but because it was thought that they would develop some imaginary “faculty of reasoning.”

Professor E. L. Thorndike recently put this to a test by having students perform problems in algebra and then giving them the same problems a little while later using a different set of letters. When the second set of problems was given, it was found that the difficulty had been increased, although there had not been a change in the reasoning involved. The students had been in the habit of reasoning with a, b, c, and x, so that when r, w, g, and p were substituted their reasoning fled.

This explains why the close scientific thinker will go astray in making investments, or why the financier is a poor scientist. Each has got into the habit of reasoning with certain facts; when these are changed, their reasoning is altered.

There is no general training. Train yourself on the job; Mah Jong trains for Mah Jong, dancing trains for dancing.

If you want skill in invention, don’t read the biographies of famous inventors: Invent! If you want skill in managing, manage something, don’t play chess!

Feign Interest

It is a commonplace that it takes more effort to do something that is displeasing or uninteresting than it would to do the same thing when it is fascinating. If someone could find out a way to make boresome tasks fascinating, he would increase the efficiency of the world several fold.

Let us see what has been done along this line. About 1905, two German psychologists, Ebert and Meumann, made a very careful study of the way memory work was improved by simply “making believe” that it was interesting, even when it was known that it was a long, boresome job. They found that merely deciding to think that the work was going to be interesting improved the work.

More recently Mrs. McCharles, at the University of California, made a more practical study of the influence of attitude on learning than that of Ebert and Meumann. When Mrs. McCharles’s subjects pretended that the work ahead of them was going to be interesting and heaps of fun, they learned much more than they had learned with their ordinary attitude or when they thought it was going to be an onerous task.

Perhaps the assumption that the work was going to be interesting really made it interesting, but whether it did or not the fact still stands that they actually learned more and with less effort than when they did not feign their enthusiasm.

This may give some explanation of the apparently marvelous minds of men such as Roosevelt. Everything the Colonel entered into, he took with him his characteristic enthusiasm. Enthusiasm is little more than interest plus energy. Interest itself usually taps all of one’s available energy. Faking an interest, whether there is a genuine interest or not, seems to be almost as effective in increasing human efficiency in learning as a genuine enthusiasm.