A few months ago I had screenwriter, producer, and director Brian Koppelman on the podcast. During our conversation, Brian mentioned that he’s collaborated with his lifelong friend David Levien on many of the screenplays he’s worked on. When Brian told me that David not only works on screenplays but boxes and writes a popular detective novel series, I had to get him on the show because, well, I’m a big fan of detective novels and boxing! In this episode, David and I discuss hardboiled detectives, the sweet science, and creativity (and how they even tie together). A great conversation with lots of fantastic insights.

Show Highlights

- How David and Brian Koppelman collaborate on writing projects like Rounders, Oceans 13, and The Illusionist

- Why detectives are an archetype of American masculinity

- What we can learn about being a man from hardboiled detectives

- Why the subway is the perfect place to write

- How boxing has helped David become a better writer

- What David learned from his grandfather’s experience fighting Joe Louis (look for an awesome guest post from David on this subject next week!)

- And much more!

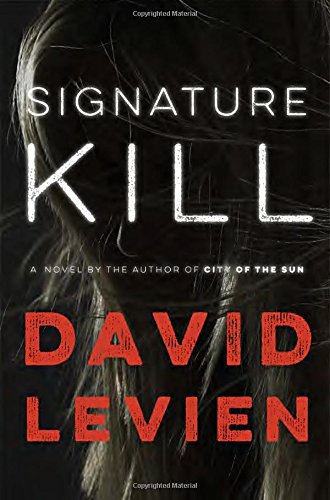

If you’re a fan of detective novels, check out David’s latest book, Signature Kill.

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Special thanks to Keelan O’Hara for editing the podcast!

Transcript:

Brett: Brett McKay here and welcome to another addition of the Art of Manliness podcast, so a few months ago we had screenwriter and renaissance man, Brian Koppelman on the show to discuss creativity, working routines, facing rejection, and what Brian had to say resonated with a lot of you, and we got rave reviews about that podcast. Brian mentioned he has a writing partner that he’s worked with for pretty much his entire career. They worked together on Rounders, The Illusionist, Oceans 13. That writing partner is named David Levien, and Brian made the introduction.

I had to get David on the show because besides being a screenplay writer, besides being a movie producer and director, David is also a published novelist, and he’s focused a lot of his work on the detective genre which I’m a big fan of. I love Raymond Chandler and all those classic hard boiled detective novels. David and I discussed creativity, his working routine, how you establish a working relationship with a writing partner or a business partner of any type. We also discussed detective novels and what men can learn from detectives and detective novel genre and why the detective has become such an archetype of American masculinity.

Besides that we talked about boxing and MMA. David is a boxer who’s dabbled in mixed martial arts as well for most of his life. In fact, his grandfather was a professional boxer who fought Joe Lewis for the world championship. We discussed what lessons David has learned from boxing and also from his grandfather’s experience through professional boxer and boxing Joe Lewis. Anyway a fascinating podcast with lots of great insights and things you can just do to plan your life today to improve yourself. I think you’re really going to like this, so let’s do this. David Levien, welcome to the show.

David: Thanks Brett, happy to be on.

Brett: You are a writer, not only of fiction but also screenplays, and you’re actually the writing partner of Brian Koppelman who we’ve had on the podcast before. You guys worked on, was it Rounders and Oceans 13 and Walking Tall or some of those.

David: Yes, Brian and I have been best friends since we were kids actually. We met when I was 14 and he was 15 or 16 on this summer trip, and we lived near each other in New York growing up. Never went to the same school but lived near each other and have been best buddies since then. A while back about 17, 18 years back, we’d each taken these circuitous routes through our careers, and we ended up at this place where we both wanted to write screenplays and make movies. I had had a lot of experience in the business because after college I moved out to LA and started working in the movie business in low-level assistant type of jobs as a reader and mainly of screenplays and then a story editor.

I read thousands of screenplays and out of the thousands there were probably a dozen good ones. I felt like I was able to identify them and understand the form through osmosis by just being there and reading so many of them. I ended up back in New York, and I was bartending. He was working as a record exec, and we decided we wanted to join forces and do a script together. We started meeting in the mornings before he went to his job and after I’d get back. I’d wake up early after bartending.

We knew we wanted to tell a story about friendship and about trying to find your destiny and all that stuff, and we couldn’t exactly figure out what world to set it in. We knew that one of the characters would probably be a law school student, though that wasn’t the path he wanted to take. Then one night at 3 in the morning I got a call and it was Brian. He had stumbled into one of these underground poker clubs in New York City and gotten cleaned out, lost every dime he had, but he loved it. He thought it was so colorful and amazing, and the next night we went back and we started going basically every night playing slash researching. We did that for about a year and met all the characters on the scene, and that’s when we knew that we’d do this poker movie. That’s what turned into Rounders.

Brett: Turned into Rounders.

David: Yeah and we’ve been working together ever since. We’ve been writing partners in the movie world. We produced a lot of stuff together, and we directed together as well.

Brett: Here’s a question I have. You guys are best friends since you guys were kids. How do you collaborate on creative work because for a lot of people I think they think something like a screenplay or a movie or directing it’s the lone artist. The lone genius working by himself. How do you fuse 2 minds into a story with the screenplay? What’s your collaboration process like?

David: You hear about these writing teams and even 3 person and sometimes even more people on a team, and it is hard to understand how all that can coalesce and turn into a single vision. For us, if people would think about the Hughes brothers or the Coen brothers, it would make more sense in a way as if because people are brothers they have a mind meld going or something. We say that we’re like brothers but we don’t have all the baggage of having grown up in the same house in a way.

Growing up, since we’ve known each other since we were kids, we’ve read a bunch of the same books, always were going to the movies together, so our favorite movies are pretty similar. Listening to the same music. We have a shared language in a way. There just seemed to be something when we started writing scripts. It’s a collaborative medium. Often it starts as 1 person alone writing this story, and then other people get involved, and it starts to become a director, camera people, all these crew members and producers and money people and stuff like that.

Our thing just starts being collaborative right from the beginning, and we would be saying the dialogue to each other. It wouldn’t be the solitary thing where you would picture an author in a room alone grinding out this prose. We’re writing these scenes that are basically, a lot of these scenes are people talking to each other, so there we are doing it before it’s barely written.

Brett: That’s cool. Besides the screenplay work, you also write fiction, write novels and detective fiction in particular. You have the Frank Behr series. I’m curious. I’m a big fan of the hardboiled detective novel that’s from years gone by like Dashielle Hammett and Raymond Chandler. Have those guys had an influence on your work?

David: Definitely. Growing up I would read those books. I love Hammett. I love Chandler, Jim Thompson that was a guy who I read everything he wrote. Lawrence Block, and I’ve been lucky enough to get to know Lawrence Block over the last little while, which is amazing. Elmore Leonard I’m a huge fan of but then other writers too. I was a big Hemingway reader growing up, and I read his fancier novels, but when I became an adult, I went back and started reading those short stories. A lot of them are hardboiled crime short stories, and his writing style really lends itself to that. It’s so terse and economical, and guys like Kem Nunn, so I’ve been a huge fan of that genre.

I wrote a couple of books at the beginning of my screenwriting career. I published too they were more what would be considered literary novels less genre, but I had this idea for the first one of these Frank Behr books in the series, you know, what turned out to be a series. At the time, it was just this 1 story I really wanted to tell about a kid who goes missing from a place where it’s not expected. He’s in Indianapolis and the midwest, bucolic setting where people aren’t really ready for that kind of thing. His father can’t let the thing go and accept it and tries a few times futilely to get private investigators involved, but they don’t do any good.

Then he happens on to this guy Frank Behr who’s my character. Behr takes on this case, and he’s got a dark, tragic episode in his past that in a way dovetails with the missing kid. It’s haunting to him, but he decides he’s going to do it, and he starts getting involved, and he starts finding what he thinks are results. Before long the father can’t sit idly by and forces his way in to work with Behr. It’s a buddy book in a hardboiled genre where these guys build a relationship as they go to try to find out what happened to this kid.

At the time I was working in the movie business, and I didn’t have a lot of free time, but I had this burning desire to be a novelist and publish books. I decided that I was going to start waking up super early before I went to work, and I had moved out of New York to the suburbs by then. I started taking the train to Manhattan, and I stopped driving because that was wasted time where the most I could do was to listen to something like listen to a book on tape or something like that.

I started taking the train and trying to grab that 40 minute block of time in my life and little by little just write 1 scene a day or a few paragraphs whatever I could, and this story came to life. It turned out well, and I was able to set the book up at a great publishing company, Doubleday, and they made a 2-book deal with me, and the series did launch from there.

Brett: You have another one coming out.

David: I do. I have the fourth one in the series coming out. It’s called Signature Kill, and that’s coming out on the 24th. I’m excited about it and working on it for a long time. It is a journey into some dark stuff. Frank Behr, my guy who’s this big, brooding guy who works on his own, sometimes a little self destructive, doesn’t build a great career for himself. Sometimes he spikes into a good situation where he can make some money and be on the right track, but he’s got a couple of self-limiting or antisocial tendencies that rear up.

He’s basically on his own. He’s got some financial pressure. He can’t figure out exactly how he’s going to find cases, and he sees a billboard with a missing young woman on it with a big reward attached. He knows it’s a hopeless case, but he decides to sign onto it.

As he starts working that case of what happened to this girl, he realizes that he’s in the middle of a bigger case overall where lots of people, young women, especially have started to disappear in the city of Indianapolis over the last many, many years but in a way that it’s not clear that it’s a serial killer to people who wouldn’t be looking or who wouldn’t want it to be broadcast. The police don’t want it to be known as that because they don’t want to create a panic. He starts to figure out that there might be linkage between what he’s working on and this bigger case, and he goes from there.

Brett: That sounds like some Dashielle Hammett. One of the novels is like that where the detective will get on a case, and he finds out it’s actually something bigger. The detective, the private eye has become this archetype of American manliness. People think of Humphrey Bogart and the trench coat, the hat, the cigarette in the mouth, stoic. Do you consciously think about masculinity or manliness when you’re developing your characters or how they’ll respond to a situation?

David: It’s definitely a manly area. My thing is set in contemporary times, so nobody is walking around in a trench coat and a hat. There’s this incredible legacy. There’s something so great about the detective and especially a detective in America because if you really extrapolate it then you’re talking about somebody who is searching existentially, and they’re looking for answers to incredibly complex questions at the heart of these cases, things that get to the heart of our existence that can’t really be found out. They can find out facts, and they can put together the way things happen. That’s just a nod at what they’re really looking for which is usually some better description of their identity.

In the good ones of these stories, the cases that they’re on have a reflection to what the detective doesn’t understand about himself. There’s a parallel, a little bit of a parallel journey going on. If the guy figures out what’s going on on the outside, he’s also discovering something internal about himself. You have these guys in a violent setting, and there’s either gun play or fist play. There’s criminals who are trying to inflict their will and take what they want in these situations, and these guys don’t want it to happen.

Brett: It’s interesting too is that the detective works outside the authority. He’s usually not a police officer. He works on his own. Maybe there’s some kind of rugged individualist thing going on there.

David: There is. My character was a cop and that went badly after a certain point due to certain things that happened in his private life. Conflict is always fun in drama, so the cops bitching at the private eye it just makes for fun scenes. I try to texture it a little because there are times when my guy can turn to the police and certain friends that he managed to maintain on the force, and they’ll help him a little bit. There’s other times when they’ll try to use him and manipulate him in ways that he doesn’t know in order to pursue their agenda through an outside person.

There’s times when they’re both working for the same ends, but that diverges most of the time, and it becomes a problem. The cops want to be the authority in this area, and certain private investigators, hardheaded ones, don’t want to listen. In real life, you’ve got guys who really work outside of the system. If you think of Pellicano who’s been in jail for a while. You know, he’s a classic example of that. He was a totally famous figure in Los Angeles, but he was operating in a way that was more criminal than almost anybody he was investigating.

Brett: It’s interesting. I’m curious about this. There’s a lot of talk about how men don’t really read fiction. Fiction is for ladies. Guys like to read biographies and success books or business books. What benefit do you think men can get from reading fiction. Why do you think they should make that part of their literary diet?

David: That’s a great question, and I do think that the publishing industry and the book companies buy into that to a certain degree. The book companies have just had much bigger success by placing these female-themed novels in these book clubs which are somehow largely female. You know, the Oprah Book Club was a huge driver of sales for books. I understand what it’s like. Guys have a lot of responsibility. They have jobs. They have families to raise. They have a lot of stuff to do. I suppose that the wrong kind of fiction can seem trifling or a waste of time for them, and they could read a book like Unbreakable or Unbroken, the Zamperini.

Brett: Oh yeah, Unbroken.

David: Unbroken or Lone Survivor and they get all of the charge of fiction out of that, but it’s a true story, and in a way it’s inspiring because there’s this great courage, bravery going on. In a way you can grasp that into your own daily thing. I understand it, but there’s the right kind of stuff for guys to read that they’ll get a ton out of depending what their interests are. There’s a lot of great writers working these days.

Brett: Some of my favorite male fiction writers are guys, I mean, specifically male fiction writers, but the authors who a lot of men gravitate to. I love they’re often very ambiguous. It never ends with a good ending, but it leaves you thinking and pondering what would I do in that situation. Cormac McCarthy, I’ve read almost all of his books and they’re all really violent, and there’s really not a great resolution at the end, but it leaves you thinking. The same with the detective novels. There’s a resolution of course. They solve the crime, but sometimes it’s not a happy ending, and I like that for some reason.

David: Cormac McCarthy is something. You think about any guy who would read nonfiction would love to read those books. You’re right, you know, sometimes things are ambiguous or sometimes because of the writing style which in his case is very elevated and also very iconoclastic, it’s hard to parse sometimes. These passages in Spanish in some of his books. There’s no punctuation. There’s no quotation marks. If somebody is on their way to work or something or has a half an hour to read, that can just be a bit of a pain.

For me it’s worth it. This is the area that I live in and toil in, so it’s natural to me. I know tons of guys went and saw No Country For Old Men when it came out, and I bet you tons of people loved that movie and probably not that many of them read the book, but it’s an incredible read too. Weirdly premium cable …

Brett: AMC-type stuff?

David: … has some really great shows on right now that have a novelistic style to them. They’re just 10 or 12 episodes that are chapters, and it’s not cheesy like some broadcast TV. There’s no commercials. You can download it on iTunes and take it in a binge or something like that. In a way, that’s supplanted what the detective novels and then noirs used to be for guys in the 50s.

Brett: Justified is a good example of that or True Detective on HBO.

David: Great examples. Love both of those shows, and you watch those, and you’re getting everything that a really good Elmore Leonard or Mickey Spillane in the old days or whatever one of those books, what you’d be going for.

Brett: I’ve read studies too about fiction helps you become more empathetic or builds theory of mind. By reading fiction, you get into the minds of other characters even though they’re fictional or other people. It builds up social repertoire in you by reading fiction. I’ve read somewhere about that.

David: That’s fascinating. That’s certainly why I would do it because it puts you in a world and it puts you in the head or voice of a person that you would never encounter. Really in a way, it’s putting you in the head of an author who some of these guys have been great thinkers or had grown in ideas or a great way to express themselves.

Brett: You refer to this earlier when you were talking about how you started writing on the train. I’m curious. Do you have a ritual to get you ready for work, but are you one of those guys like Steven King where it’s just like, “It doesn’t matter what I’m doing. If it’s on the back of a napkin. If I’m going to create something, I’m going to create something. Things don’t have to be perfect.”

David: I certainly wouldn’t compare my output to Stephen King’s. That guy is just a phenom how he does it. I’ve read some of his books on writing, and I actually can’t remember his exact way that he goes about it, but clearly the guy is just a natural. For me, I try to make it less about a ritual because if you build a ritual, it can be a great way to insulate yourself from actually doing it. You can start to get elaborate with that stuff. You know, you need your room set up in a special way, nobody can be around, it has to be the right time of day, you have to have the right materials, you have to be in the right mood.

You can just basically if then any part of that isn’t right, you’re starting to make an exit for yourself from doing the task at hand. You can tell yourself that the ritual wasn’t lived up to, so how could you be expected to do your work or do your best work. I try to not be too precious about that stuff. I get up. I read the paper for a little while, get ready for the day, take my kids to school which is a good time. I drop them off and then head for the train. It’s a 42-minute ride, and there’s something about the fact that it’s short that’s very freeing because it doesn’t seem too punishing.

It’s just like, “Okay, just do whatever happens. How much expectation can you have? Nobody expects you to write 10 pages. You’re getting up out of this seat in 40 minutes, so whatever happens happens.” Sometimes I grind out a couple of sentences and end up just staring into space. Other times I like to pack up my stuff and jump off the train before the doors close, and they take it back to the train yard or something because I got on a roll. That’s how my day starts.

Someone who’s fortunate to do what they love, so writing is my day job or creating stuff is my day job, so parts of it are long periods of writing these screenplays and teleplays, so I’ll end up in my office shortly after getting off the train and then I’ll have a day of writing ahead of me. The day of writing at times isn’t even as concentrated as the 40 minutes because the phone will start ringing, they’ll be stuff to deal with.

Brian and I, we could just be in a different head space where one of us wants to talk something through. The other one wants to write something down or 1 guy wants to write dialogue, and the other guy wants to keep going with the outline. Out of the bigger portion of the day, sometimes you’re just looking for a way to capture quality minutes also.

Brett: Got you.

David: I remember when I was younger trying to make everything perfect and clear in my day so I could write for hours and cover page after page, and it was almost crippling. Then I read something that Carver wrote about writing, Raymond Carver, great short story writer. He said he had always planned on being a novelist, but he had kids when he was young and it was always he had to be a teacher to make money. Every night he had to help doing the laundry and cleaning the dishes and making his kids lunches the next day.

He realized he was never going to have more than a 45-minute or hour or 2 hour patch in his life, and he better write something that he could finish in that amount of time, so he started writing short stories and just forgot about the novels and became one of the best ever.

Brett: Wow so he had the constraints helped him.

David: Yeah, I guess you’ve got to find a way to make these limitations work for you, because otherwise they really are going to be limitations.

Brett: This is something interesting about you. Brian told me you have a background in boxing and martial arts. Correct?

David: I’ve been doing that stuff for years not as a serious. I’m not out there as a club fighter or even amateur fighter. I have to protect the mainframe. I’ll spar, I’ll wear headgear, and it won’t be too crazy. Generally I’ll be sparring the trainers now instead of guys at the gym. I’ve been boxing for a while. I’ve done martial arts. I do Brazilian jiu jitsu. I’m into it. I love MMA, and I’m getting on the older side for that. I’m 47, but it keeps you in great shape, and it makes you feel alive. Whenever I go to do some other stuff like tennis or golf or something, it’s like sleepwalking. When you’re in there rolling with somebody or sparring, you just really feel alive.

Brett: It’s interesting that a lot of those manly writers that we think of as the iconic ones like Hemingway, Jack London, both were avid boxers. I’ve read, this guy, he’s a philosophy professor, I forgot where, but he wrote an essay. He’s a boxer too. How boxing has helped him in philosophy. I’m curious. Has taking part in martial arts, boxing, has it helped you in any ways with your creative and intellectual battles in your work?

David: It’s helped me in numerous ways I’d say. For one, any experiential information that I gain by practicing this stuff has been put on its feet in my books because Frank Behr lives in a world where he’s not doing this stuff as sport. He’s constantly, he’s living this rough and tumble life as this private investigator, so I can use the details that I’ve learned for him. He’s a guy who is an experienced street fighter, and he’s a big, tough guy. He knows firearms. He knows hand to hand and all that stuff, so there’s always scenes in the books that cover it that I get to inform with a lot of real life detail, so that’s great.

I think what you’re asking is what does it do on a psychological level. Pursuing filmmaking or writing novels is definitely a discipline because you can only go little by little, and it’s daunting, and it takes a long time, and there’s a lot of room for self doubt. There’s a lot of ways that you can get distracted and get off course. Even if you have deadlines there’s always a way you can make up an excuse if you’re not careful. Training in these arts is, you have to be super dedicated. That’s one of the reasons why I keep the sparring or the rowing and jiu jitsu in there because that’ll force me to keep up the strength training and force me to keep up the cardio.

The downside of not doing those things is so vivid when you go into the third round against some guy who’s 25 years old and works in the gym as a boxing trainer and does it all day long. Now whatever semblance of skill you had starts to fade because you’re crapping out, and you have no more gas because you haven’t been doing your running and lifting and everything. It’s a disaster. I mean, you’re totally hosed at that point. You’re just going to immediately get physical pain as your reward.

It forces you to keep up the discipline, and then that does transfer over. Because sitting there and writing a hard scene or doing something, rewriting a book or something, it’s just not going to seem as difficult if you’ve put yourself through the roadwork and all that stuff. It’s a mindset.

Brett: Got you. Boxing runs in your family. Your grandfather was a boxer, and he actually fought Joe Lewis for the heavyweight championship of the world. Tell me about your grandfather and how did that fight go down?

David: My grandfather, his name was John Paycheck. The country singer guy, you know the Take This Job and Shove It guy, Johnny Paycheck, took his name from my grandfather.

Brett: Oh wow.

David: Actually took the stage name. He lived on the south side of Chicago. He was super poor growing up. He got into boxing. He was really good. He was the top prospect in the US. He fought Golden Gloves for the US. He won the Golden Gloves against Ireland and knocked this guy out, broke his jaw. He was a top prospect when he was 19 or 20 years old. He was a heavyweight, but it’s ironic because I don’t even think he touched 190. He was 188 something like that. Very small heavyweight. Joe Lewis wasn’t super big either, but he was definitely bigger than my grandfather.

My grandfather was having a really great string of fights through the midwest, and it was around the time when Joe Lewis got drafted into the army, and they knew he was going to go in 6 months or a year or something like that. They organized the bum of the month club, you know it’s pejoratively called that now, where they wanted to book him a fight a month, so he could make a bunch of money before he went into the army and couldn’t fight for a while. They started to reach out to these likely prospects.

I’ve seen footage of the fight, and it’s so hard to watch because there’s my grandfather, and he gets knocked down 3 times in the first round, he survives the first round. In the second round he gets taken out with a left hook through the left hook. I remember talking to him about it when I was young when he was still alive. He said, “You know, when I went in that night, I was dry. I couldn’t get a sweat going because I was nervous.” He said, “When he hit me with his jab, I felt it. It hurt me.” He said that he’d never been, you know, he wouldn’t get hurt by a jab. You get thrown off a little by a jab, but Lewis’ jab actually hurt him.

Before long it was over, and I used to always think about it. The thing that I learned about him as a fighter was that he was extremely tough. He didn’t become a legend, but he got a shot at a legend. He got pretty close, and the realities of the fear and the pain hearing it from a guy who’d been in there was totally eye opening because as a fight fan, you never actually hear about that. Nobody ever admits that in the post fight interview. They just say it wasn’t their night or whatever. There was that side that I learned back in the day.

It’s funny, as I got older, one of the first things I wrote, the first thing I published was in Ring magazine actually. It was a story about my grandfather, and it touched on that fight and stuff like that. As I got older, I learned something else. This guy reached out to me, an old man who was friends with my grandfather, reached out to me after the article came out. He told me how the fight came together. That was a real education in the way the world worked which was he wasn’t just some rube who thought that he was going to beat Joe Lewis.

In fact, when the fight offer came in, they said, “You know, we want you to fight.” I can’t remember the date exactly, 1941 at the Garden in June or something like that, Madison Square Garden. He and his camp said, “The kid is not ready. He needs another year, so we’re going to turn down the fight.” The promoter strong armed him and said, “He’ll either be there that night at the garden or he’ll never fight in the garden for the rest of his career.” It was an amazing first-hand lesson in just how crooked the game has been and how it’s always been that way.

I didn’t just feel like he was an athlete who lost. I felt for him as a young man who got bulled into something that was bigger than him that there was no way he could have actually pulled off.

Brett: Yeah and you just have to take it. I don’t know. I think we’ve all been in one of those situations where you’re forced into something, and you just have to make the best of it.

David: Sometimes you just find yourself taking it and you just hope you can take it like a man.

Brett: David, this has been a great conversation. Where can people find out more about your work and when does the next book come out?

David: The next book comes out on Tuesday, March 24th, and it’s called Signature Kill. My website is David Levien dot com, and my last name is L-E-V-I-E-N, so a little unusual spelling, David Levien dot com, L-E-V-I-E-N, dot com. All the info is on there.

Brett: Fantastic. David Levien, thanks so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

David: Thank you, man, appreciate it.

Brett: Our guest today was David Levien. He is a screenwriter, movie producer and director and a novelist. His latest novel in the Frank Behr series dropped last month. It’s called Signature Kill. If you’re a big fan of detective novels and if you’re not, go pick it up. You’ll find a new genre of literature you’re going to like. I’m a big fan of it. You can find that on Amazon dot com.

That wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at Art of Manliness dot com. If you’d like to support our podcasts and support the website, one thing you do is go to Store dot Art of Manliness dot com and pick up some of our Art of Manliness gear that we have there. We’ve got a fantastic really manly coffee mug that we’ve gotten rave reviews about.

We put a whole bunch of t-shirts on clearance for the spring so go check out the clearance section. Anyway, some great stuff there. Go check it out. Again, store dot Art of Manliness dot com. Your purchases will help support the continuation of the site and the podcast. Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.