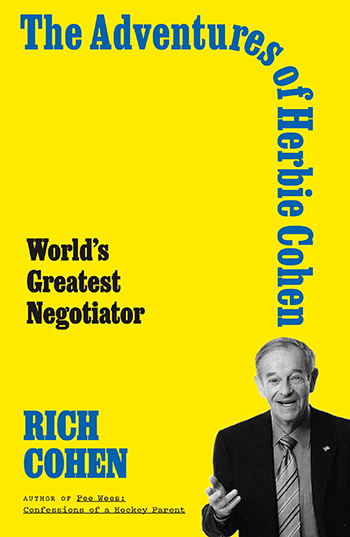

Fast forward to today, and his son, Rich Cohen, has written a memoir of his father’s life, and life philosophy, called The Adventures of Herbie Cohen: World’s Greatest Negotiator. Today on the show, Rich shares stories from Herbie’s life, from his colorful childhood on the streets of Brooklyn where he palled around in a gang with future famous figures like Larry King and Sandy Koufax, to coaching basketball in the Army, to becoming a sought-after strategist and dealmaker. Along the way, Rich shares the life lessons that grew out of those stories, including how power is perception, and why you need to care, but not that much.

Resources Related to the Podcast

- You Can Negotiate Anything by Herb Cohen

- Larry King tells the Moppo story

- Larry King tells the Carvel story

- AoM Article: How to Haggle Like Your Old Man

- Podcast #234: Haggling and Deal-Making Advice From a FBI Hostage Negotiator

- AoM podcast and article on the OODA Loop

- AoM Article: The 7 Habits — Think Win/Win

- Sunday Firesides: Care, But Don’t Care

Connect With Rich Cohen

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. In 1981, Time Magazine stated, “If you are ever in a crucial life-changing negotiation, the person you want on your side of the table is Herb Cohen.” Cohen was then known as the world’s best negotiator, and had worked with Fortune 500 companies, professional athletes, and US Presidents, and also penned the best-selling book “You Can Negotiate Anything.” Fast forward to today, and his son, Rich Cohen, has written a memoir of his father’s life and life philosophy called “The Adventures of Herbie Cohen: World’s Greatest Negotiator.” Today in the show, Rich shares stories of Herbie’s life from his colorful childhood on the streets of Brooklyn, where he palled around in a game with future famous figures like Larry King and Sandy Koufax, to coaching basketball in the Army, becoming a sought-after strategist and deal-maker. Along the way, Rich shares life lessons that grew out of these stories, including how power is perception and why you need to care but not that much. After the show is over, check out our show, that’s in at aom.is/herbie.

Rich Cohen, welcome to the show.

Rich Cohen: Yeah, thanks for having me.

Brett McKay: So you have written a memoir about your father, Herbie Cohen. Younger listeners probably haven’t heard of your father, but people who grew up during the 1980s, they probably heard of him. He’s a big deal. He was a pop culture phenomenon. What was your dad famous for?

Rich Cohen: He’s from Bensonhurst, Brooklyn and he’s a negotiator, a job that did not exist that I believe he invented. And he ultimately, at the top of his career, he worked for, it seemed like, every Fortune 500 company, either representing the company in their deals or training their executives how to negotiate. And he did other things like he trained all the SWAT teams, and I’ve been hearing from the guys who he trained how to negotiate with terrorists. He worked in several presidential administrations, he was brought in by Jimmy Carter during the Iran hostage crisis. And he worked for Reagan. And then he was on the START talks, which means he negotiated nuclear proliferation with the Russians. He also worked for the NFL players, and the Major League umpires, and a lot of the unions. So he sort of did everything. And what always interested me about him was he kinda made up his career. I mean, that thing, that didn’t exist. And then the big thing was when I was 12-years-old, he announced he was gonna write a book, went down to our basement and came up with this manuscript, handwritten in longhand, and it was rejected by 22 publishers before one not, finally accepted it.

And it was called “You Can Negotiate Anything: How to Get What You Want.” It was published in 1980. And I think, I’ve written like 13 books. His book alone still outsells everything I’ve written every year. So his book became kind of a classic. They read it at Harvard Business School, Yale Business School, which is funny to me ’cause he’s just sort of a street kid from Brooklyn, and he is now the expert.

Brett McKay: Yeah, it’s funny. You said that he made up his career, and it seems like he basically used principles and ideas that he got while just living, growing up in Brooklyn, being in the Army, and codified it and made a job for himself.

Rich Cohen: Yeah, his parents are immigrants, and he believed first generation American, and his whole thing is about power and institution. He learned that what became his sort of motto in life, which is that power is based on perception. If you think you got it, you got it, even if you don’t got it. And to make that point, he actually began his book with a story about me in a restaurant as a nine-year-old freaking out, showing that I was able to use my limited power as a kid to get what I wanted, which was not to eat in that restaurant, and they dragged me out of there. So his point was that he kinda wanted to demystify the idea of negotiating which people were intimidated by, and show that it was something that you’re engaged in all the time with your family, at your job, even if you don’t realize it. But if you do realized it, then you can actually become much better at it and to turn it into a game and have fun at it. So this is all the stuff he learned as a kid, and that’s why his book, I think, connects so much with people, ’cause it isn’t written like an academic book; it’s like stand-up comedy.

And that’s why it was important for me that my book be funny, that you actually, hopefully, laugh out loud when reading it. Because to me it’s like, you know, it’s like the Bible story, which is, there’s the life of Jesus, this then there’s a teaching of Jesus. I’m not comparing my father to Jesus, but his life was very funny and he did good things and bad things, and out of his life came his philosophy. So I wanted to sort of share both.

Brett McKay: Well, yeah, it was hilarious. I mean, as I read it, I was laughing out a lot. My wife was like, “Is that book really… ” I said, “This is hilarious. It’s so funny.” And so this idea that power was based on perception, that he learned this really viscerally. He understood this as a nine-year-old, him as a nine-year-old. And it happened when he was deputized as a school crossing guard. Tell us about that experience. How did he learn that power is based on perception being a school crossing guard?

Rich Cohen: Well, the key to his whole thing is that your enemy in life and in negotiating is kind of a narcissism. Which is people tend to think, especially under stress, that they’re the only players, that they’re the only one that had anything at stake, and they don’t realize that who the people they’re dealing are under stress too, and they’re also have a tough situation. Now, the story you’re talking about is when my father was nine-years-old, he got in trouble at school. And as a punishment, he had to work as a crossing guard at kind of a cross-walk that didn’t really need a crossing guard. And he met another kid, Larry Zeiger, who later became Larry King, he was his best friend to his whole life, who was also in trouble, and he was also put on this duty. And they put these crossing guard belts on them, and they sent them out to the corner. And Larry was complaining that this was busy work and crap. And my father said like, “No, I… ” He’s a nine-year-old. “I think you misunderstand this position. We have a lot of power. They’ve given us a lot of power.”

And Larry disagreed, and they made a bet. And to prove it and win the bet, my father took a stop sign and went out and just stopped traffic for five minutes. And quickly, you had wall-to-wall traffic in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. People honking, screaming, swearing, getting out of their cars and getting into fights, until a teacher had to finally come and drag them out of there. My father was just like when in a movie when they ripped off the guys, you know, sergeant stripes. They ripped off their crossing guard belt and kicked them back to class, but the lesson was proven, which is, if you think you got power, you got power.

Brett McKay: Well, he had another experience later on in life when he was an adult, and also involved Larry King, where this idea, the power is based on perception. I think Larry was at a Democratic National Convention.

Rich Cohen: Oh, yeah.

Brett McKay: And your dad was like, I’m gonna be there on the stage with you. And Larry’s like, bulk crap, not gonna happen.

Rich Cohen: Well, you’re missing… I don’t know, I’m just gonna go to it. Now, you’re missing the crucial story, which is the famous Mapo story, which I grew up when Larry was on the radio, it sets up their whole relationship, and this is a story Larry would tell on his radio show, and it became kind of a cult story. Larry told it not long before he died again on Jimmy Kimmel, you can look it up, but he says, This is what made my father a negotiator, which is, when they were 14-years-old going into ninth grade, which then was the last year of junior high school in that part of Brooklyn, they would walk to school every day with a kid named Gil Mermelstein, who they called Mapo, because he had like a big mop of hair on his head. And they went to pick him up and his house is all closed down. And his cousin was there and they said, Where is Gil, where is Mapo? And they said, Mapo has tuberculosis, and he’s been sent to Arizona for the cure, and I am here to close up the house, disconnect the phone and go to the school and get his records sent out there, so he can go to school out there.

And my father said, You know, your life’s busy enough, you don’t have to go to the school, we’ll go, we’ll tell the school what happened. And it was my dad, Larry, and another guy named Brazy Abadi, and the three of them were walking to school, and my father said according to… This is Larry’s version. My father’s version, slightly different. He said, you know, I got a great way to make $20 bucks, so we can go to Coney Island and have a party. And Larry said, what? He said instead of saying Mapo is sick in Arizona, we’re gonna say Mapo died [chuckle] and raise money for a funeral wreath, and we’ll take that money and go to Coney Island. So, my dad talked these two other kids into it, and they went to the front office at the school and they said Mapo has died, and the front office called Mapo’s house and they got a disconnect and they wrote deceased on Mapo’s card, and then my dad and Larry went around to all these classes and raised, I think it was just over $20.

And the other, Larry and Brazy, were freaked out about it, they’re gonna get caught, they’re gonna get in big trouble. My father said, by the time Mapo comes back, we’re gonna be in high school, and we’re like in a totally different jurisdiction, they won’t be able to do anything about it even if they find out. So the year went on and they got a call to go to the principal’s office near the end of the year, and they thought they found out, we’re in big trouble and Larry and Brazy were freaking out, and the principal rather than big trouble said, Listen, we’re starting a new thing for our junior high public service award called the Gil Mermelstein Memorial Award, [chuckle] and the first winners are gonna be you three for raising money for the funeral wreath for your friend and remembering your friend. So Larry and Brazy are freaking out again, we’re gonna definitely get caught, there’s a huge assembly scheduled, they’ve made an award, there’s gonna be newspaper reporters there. My father said, No, this is even better. Same deal, except now we’re gonna get an award, and by the time Mapo comes back, we’ll be in high school.

So the way they tell the story is they’re at this assembly, there’s a big banner over the top of the theater that says, Gil Mermelstein Memorial Award, there’s a big trophy up on the stage. My dad, Larry and Brazy are there, there’s a New York Times reporter there, the principal’s there. And as Larry tells it in the most amazing recovery in a tubercular medicine, the history of tubercular medicine, Mapo returns to school that day. [chuckle] And he goes into the school and the school’s empty, and he’s confused and he goes to the office, they don’t recognize him, he says, Where is everybody? They say they’re in the auditorium for an assembly. And he goes into the auditorium through these big doors that clank, and he’s standing at the back of an auditorium. My Father would always say Mapo wasn’t that smart, but he knew what the word memorial meant, and he knew if your name was next to it, it meant you were dead. [chuckle] And the kids in the back of the auditorium looked around and they recognized Mapo, and they immediately understood what my father and Larry had done, ’cause they were always doing crap like that and laughter spread from the back to the front, and the principal looks up, he doesn’t even recognize Mapo, and my father’s standing there, he sees Mapo, and he jumps up and he yells through cupped hands, go home Mapo, you’re dead, you’re dead. [chuckle] And Mapo turns and runs.

And the principal understands what happens, he destroys the trophy, sends everyone back to class, he’s going nuts, he calls them into his office and he’s screaming at them that they’re never gonna graduate. Their academic career is done. They’re never gonna go to high school, they’re gonna need to get a GRE, they need to go to trade school, forget about college. And Larry and Brazy are crying, and this is when Larry’s says my father’s first negotiation, he says, Hey, principal, you’re making a big mistake, which is like shocking to the principal. He’s like, Why am I making a big mistake? He goes, Think about it. This is my father’s whole thing, which is, he always says, to understand the price, you have to understand the player. Other guy has something at stake too. And if you can see the world through his eyes, you can understand what that is. Figure this out intuitively, ’cause he was a kid, but he said, Yeah, we’re gonna get expelled and yeah, we’re probably not gonna get to go to a normal high school. But what’s gonna happen to you? I mean, two, three bad kids come in and tell you another kid died, you called his house, you write deceased on his card and then you give them an award? I mean, yeah, we’re never going to high school, but you’re never working in this city again.

And Larry said, the principal just leaned back in his chair and just sighed, he was whipped. And he said, Let’s just forget the whole thing. And he sent them back to class and they graduated on time and everything, and it became this running gag, the Mapo story. But that set up this idea for Larry, that my father can kinda get him out of any jam that there was. So Larry, if you know Larry’s history, he was often getting in trouble, and a big part of my childhood was Larry calling my father, asking my father to figure out how to get him out of that trouble. And another thing with my father is, he uses the same ability to get in anywhere, because he believed that if you act like you know what you’re doing, people just believe you. When I was a kid, he said 98% of the people in the world are schmucks. They’re morons. You just act like you know what you’re doing, even if you don’t, you’re ahead of everybody, that’s if you think you got power, you got it. And one of the things you could do with my father, if you wanted the tickets to something, you’d say, you can’t get tickets, it’s sold out, or you’ll never get in and he’d get in this sense and he’d go, I’ll never get in, you’ll never get in. I’ll get in.

So the story is, Larry was in New York for the Democratic convention, the one that nominated Bill Clinton at Madison Square Garden, and my father and Larry and me and some others were having dinner, and my father said, Larry, I’ll meet you tonight at the Garden to see Al Gore’s speech. And Larry said, “No, you’ll never get in. I don’t have credentials for you, and there’s tons of security. You’ll never get in.” My father said, “I’ll never get in? I’ll see you tonight.” And Larry writes about in his book, and right before he interviews Gore, there’s my father’s standing next to him on stage. And he was like, “Larry, was mystified,” like, “How the hell did he get in?” I know how he got in ’cause I have a reporter who saw him do it, which is he walked up to the head guy running security with a notepad, and he started asking him all these questions about, “When’s your shift end? How many people are working here? Is there anything going on at door number seven? What’s going on on Seventh Avenue?” And the guy just assumed my father was his boss, answered all these questions, my father wrote it all down, and said, “You know what? You’re doing a great job. Congratulations.” Patted him on the back and walked right through. And that was a win-win, ’cause my father got in and the guy ended up feeling very happy.

Brett McKay: Alright. So there are two principles of negotiation that you can apply right there. Power is based on perception, so if you act like you know what you’re doing, people typically are gonna treat you like that. And then also, the other one with the principal, understand the motives of the other person involved. They’ve got goals as well. And if you understand that, that can unlock a lot of things.

Rich Cohen: Right. And think about as if everybody had a different kinda money. And when most people go on negotiation, they’re assuming, My dollar and your dollar are the same. So I’ll offer to trade my dollars for your dollars. The other person has completely different money. So you have to figure out what that money is to figure out what’s gonna move them. And that money is any kinda different motivation. In the case of the principal, his career was his money.

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Rich Cohen: If that makes sense.

Brett McKay: No, no, that makes perfect sense. So your dad group in Brooklyn. I thought it was really interesting. I didn’t know about this, that you kinda give people a look into the world of Brooklyn in the 1950s, there’s these things called social athletic clubs, they’re basically gangs. And your dad and Larry King belonged to one, called the Warriors.

Rich Cohen: Yeah. I grew up with stories. It was very romantic and exciting for me ’cause I grew up outside of Chicago, very suburban. And when I talked about my friends on my block, they were Todd, Mark, Dennis, Jamie, Chris. When my father talked about his friends on his block, they were Inky, Sheppo, Hoo-ha, Gutter Rat, who was called that even by his own mother, which I always sound amazing, as in, Gutter Rat, come in, it’s time for dinner. My father insisted he even called Handsomo, ’cause he was so good looking, was what he’d say. And they had this club room in a kid’s basement. And they were called the Warriors, mainly because there was a Pontiac dealer in their neighborhood, and the logo for the Pontiac dealer was a giant Indian head, and they could basically swipe stuff from the Pontiac dealership and have grade A insignia. They had jackets, which I have a picture of my father, and was a blue jacket with a white W, I think, but it was reversible for formal occasions.

And mostly what they did is, they hung around on the corner of 86th street and Bay Parkway, they went on adventures all over Brooklyn, and they sat around their clubhouse, just kinda bullshitting. And it was called the SAC, Social Athletic Club. And one time, one of their members complained that all they do is athletics, there’s no social part. And they explained that, Well, we’re socializing when we’re playing basketball. So there’s the social part of the Social Athletic Club. And mostly, they played basketball, softball and baseball and roller hockey.

Brett McKay: And they also went on this adventure to New Haven, Connecticut, ’cause some guy were selling three scoops of ice cream for 15 cents. And for some reason this was worth the driving in a blizzard to go check out, to verify this was true.

Rich Cohen: This is another story that Larry told on the radio all the time, called the Carvel Story. And it was like the B side. If the Mapo story was the A side, this was the B side. And Carvel Story was great because the person who set the whole thing in motion with Sandy Koufax, because they had these guys in their neighborhood like just Sandy Koufax, who didn’t play baseball at the time, he played basketball. And he was hanging around on the corner, and he started talking about a vacation his family had just gone to New Haven where you can get three scoops at Carvel, three scoops of ice cream for a dime. I think it was a dime. Anyway, they didn’t believe this, because in Brooklyn, it was two scoops for a dime. So they started arguing about profit ratios and if it was even possible. And finally, they made a bet. And the only way the bet could be solved was by actually going to New Haven. My father had a car. He got his car, they picked up their friend Hoo-ha, and to me, always the funniest part is Hoo-ha tells his parents he’s going to Carvel, and there’s a Carvel on the same block where they live, and his parents say, Okay.

And they leave, they drive past that Carvel, and they get on basically the Belt Parkway, and they head into the city. And it’s not until they’ve gone all the way up into Westchester County, which is like a 30-minute drive, that Hoo-ha finally says, “Where the hell are we going?” And they say, Oh, we’re going to Carvel. He goes, “Carvel is way back there.” And they explained to him about New Haven and the three scoops, and he says, “It’s impossible. You can’t get three scoops for 10 cents,” and he immediately forgets his family and is involved in the action. And they go up to New Haven and it starts snowing. There’s the Carvel closing up, and they bang on the door, and the guy lets ’em in, and they have a whole argument about how they’re gonna do it, and basically just put a dime on the counter and say, Give me what that’s worth, ’cause they don’t want anybody signalling anybody, and the guy serves three scoops. And they can’t believe it. Sandy wins the bet. They eat all this ice cream.

And they come out, and also the guy realizes now why he’s kinda going out of business. He’s given away a free scoop every time he serves ice cream. And they come out and there’s a blizzard, and it’s a whole crazy story where there’s a parade in the middle of the night, and it’s a parade for the Mayor of New Haven, and they wind up going to the parade, and my father starts going around the crowd at a party that follows the parade of campaign workers, and talks about how Larry’s done more campaign work for anybody. And then Larry starts saying how my father has done more campaign work. And the Mayor gets up and he says, “I’ve been hearing about these two young men. They should get up because they’ve done more campaign work.” And Larry gets up and he introduces my father. My father does a 10-minute speech about democracy in America and the greatness of America. He says like, “Everybody’s crying by the end.” And as they leave, the Mayor pulls ’em aside and says, “I’m very embarrassed because you’ve done all this work and I don’t even know who you are.” And of course, he wouldn’t know. They came from Brooklyn. And they explained about the three scoops, and he can’t believe it.

And what’s funny is, years later that Mayor ended up becoming a Senator, I think, or a representative from Connecticut, and he was on Larry’s radio show, and he remembered the whole thing, and they wind up getting back to Brooklyn at 4:00 in the morning, where Hoo-ha’s parents are waiting outside in the snow, and I always think of this ’cause Hoo-ha’s father goes down the row and pokes them each in the chest and goes bum, bum, bum. You are a bum, you are a bum, you are a bum. And then he asked, what the hell happened? And they say, Well, Sandy said, in New Haven at Carvel you can get three scopes for a dime. And he says, three scopes for a dime. That’s impossible. That’s the kicker of the story.

Brett McKay: Well, another example there of power is based on perception, they went into this party for this Mayor and sort of, Yeah, Larry’s a great… And they believed him ’cause everyone thought that they sounded confident and it must be true.

Rich Cohen: Yeah.

Brett McKay: We’re going to take a quick break for a word from our sponsors. And now back to the show. Well, so your father graduated high school, he was in college for bit kind of flounders, and he decides, the Korean War is going on, I’m probably going to get drafted anyway, so I’ll just sign up and join the army.

Rich Cohen: Right.

Brett McKay: And he gets shipped off to Germany kind of on the front line between Russia and the rest of Western Europe. But he ends up becoming this basketball coach for this army intramural league in Europe. And again, there’s some like there’s like lessons that he learned being a basketball coach that he later applied into his career as a negotiator. So what are some of those lessons that he picked up as a basketball coach in the army?

Rich Cohen: Well, I should say that my father believed that any game properly understood becomes a metaphor for life, so for him, everything that you needed to know about how to get by in life, you could see on the basketball court, and in his neighborhood basketball was king. So, When he got it, it was a crazy story, but he ends up [0:22:23.7] ____, which is where the Russian tanks will roll through in World War II, and he was riding on the back of a half-track with a big gun basically pointing at the Russians across the line, and his unit was all trained in behind the lines guerrilla tactics, because if there was a war, then they would instantly, most of them would be killed right away, and the ones who survived are behind the lines and they had to basically be trained in guerrilla tactics, so there was a basketball court and everyone’s playing basketball, and there was a three-on-three tournament, and he took a team of mediocre players and got all the way to the championship of that tournament, and the guy who ran the base was a colonel, I think, or general, saw what he did and call him in and said, you now, How did you do that? And he has a whole philosophy about how good can be great, mediocre can be good if you have a strategy.

So he made him the head of the basis team, which played in this second division of the European League. Now, the European League had a lot of college basketball players, a lot of NBA players and future NBA players, was a very high level, these were guys that had been drafted, that we’re going to go on and play pro ball, and he was in the second division, and he had his unit, his base had a pretty mediocre team, so his whole thing about anything in life is control the tempo, take away the other side’s strength, so he knew the teams they were playing were much more talented and much faster, so he designed an offense that intentionally slowed down and frustrated the other team, was kind of winning ugly, and then he took this kind of mediocre team, playing this very slow plotting style of basketball that would ultimately cause the other team to become frustrated and screw up, and he brought them all the way to the championship. And then that was noticed by the guy he played against in a team that had a lot of skill, was under performing in the first division, may ask him if he would take over a team and coach it, and he went and he just watched that team, and that team was very talented and very fast.

And he built a completely different strategy for that team, which was all about using speed ’cause he would say, I can teach you how to shoot, I can teach you how to dribble, but I can’t teach you how to be fast, basically, he took that team with a totally different cell and they won first division of the all European championship. Now, for me as a kid, he told me these stories, I didn’t really believe him, but then I found the scrapbook that somebody put together that had articles that Chronicled this whole thing in stars and strikes, some of those pictures are in the book. And he has this thing, it’s a TIP for negotiation, time, information, power. The first thing he did when he took over any one of these things or anything, is gather as much information as he could, he wanted to know the truth about his team and the truth about the other side, if they were better, he wanted to know that, he didn’t want any kind of bullshit, you know, he wanted to know the truth, and then he designed his strategy around that, and the other thing is, if you control the clock, that’s time, you control everything. And one thing he said that goes with this, he used to say, as long as you get there before the meeting is over, you’re never late, so basically, all that came through in basketball.

Brett McKay: The whole idea of controlling tempo. That’s actually from my warfare strategy too. John Boyd, this guy that built the thing called the OODA Loop, like observe-orient-decide-act.

Rich Cohen: Yeah.

Brett McKay: Have changed battlefield tactics in the latter half of the 20th century, and this whole thing, you got to control the tempo, if you control the tempo, you control the battle.

Rich Cohen: That’s exactly… And you put the other side off rhythm.

Brett McKay: Right.

Rich Cohen: No matter how good they are, they’re off, so their passes miss and then they become frustrated, and once you get them frustrated, they’ll start beating themselves by making mistakes, and it goes to this bigger idea, which is, you know, he always says this thing which is, a nose that can hear is worth two that can smell, which basically means being different and being weird is good, you always want to wrong foot the other side, they think you’re going to do this, you do that, you are gonna go this way, you go that way, and that’s all in basketball. And it’s all in life, so I’ve never really talked to him about war tactics, but I’m sure that he would say, like I said, it applies to everything, and sports is the closest sort of… You know, he ended up working and studying and being involved in Game Theory. My father, when I was a kid, he taught at the University of Michigan, he was never an academic, but they bring him in to teach these seminars and these classes, and there he became introduced to the game theory and the idea of there being four possibilities in a game, which is: Lose-lose, that’s nuclear war, both sides lose. Lose-win, you lose they win. Win-lose, you win they lose, or win-win.

And he’s the guy who’s sort of popularized that phrase, he took it from academia and brought it out into the world as his idea being that like a lot of people would prefer win-lose to win-win, believe it or not. And they have a sense that there’s a zero-sum game if they win, I by definition lose. But his belief came to be that in a negotiation, the only way to really win in the long-term is win-win, and he used to say, or he still says, “People will support that which they create.” So if you allow somebody to help create a solution, then they’ll be invested in making the solution into a long-term success, whereas by if you stuff their head down in it and make them eat dirt ’cause you beat them so badly, you’re just sowing the seeds for the next conflict. And the war example, this is World War I, World War I, France wins Germany loses, but is that really what happened? Because it’s set up the conditions in Germany, the peace was so harsh on the Germans that it set up basically seeds and the animosity that resulted in World War II where kind of everybody lost. So it turned a win-lose into a lose-lose.

Brett McKay: Right. Okay, so your father, he does this stint in Europe, comes back, he gets involved in the insurance industry and he kills it there because he’s applying these principles that he’s been using since he was a kid in the insurance industry. And then he finally realized I could be doing this on my own, I could be my own boss and do what I’m doing. This is how he becomes the negotiation guru, is this when he starts making his transition to freelance negotiation?

Rich Cohen: Yeah. The Insurance thing was really important, which is it happened kind of by accident, he didn’t have any money, now he has two kids, living in a little tiny apartment, and he was going to law school at night and that was paid for by the GI Bill, but he needed money for his family. So he took this job at Allstate just as a temporary thing, and they made him a claims adjuster and quickly he started out performing everybody as a claims adjuster, claims adjustments and negotiation. So then they made him head of his whole branch, he had to train everybody else, and then he just kept rising until he was running sort of the claims adjusting in the north east, and then eventually they wanted him to train everybody. And they moved him to Chicago, and then they moved him into the executive suite at Sears, which was like Amazon at the time, it was a huge company. So he went from sort of claims adjuster to an Executive Vice President at Sears, and very simply, all his big realization that claims adjusting was is better to over-pay and settle these things quickly, than to get bogged down in little fights that ended up costing you more money even if you won. It was like a big picture thing. And his big thing was always, people lose the forest for the trees, they lose the tree for the knot hole and they lose the tree itself for the knot hole in the tree.

And then Sears started having him negotiate their deals, train their executives and then hire him out to all their affiliates to teach their people to negotiate, ’cause they owned a lot of companies. And at some point he decided, Listen, I can just hire myself out, I can take the jobs I want, and I can cut out the middleman, and he started out by running negotiating programs for other companies around the Midwest, like he worked for Montgomery Ward, then he worked for the Chicago Police Department, and it went on and on and bigger and bigger, until finally he was asked to come in and train the guys at the FBI. And then the FBI started using him in negotiations, and one of the kind of coolest things he did is with this guy named Walter Cyrene, he helped set up the FBI’s behavioral science unit. And there’s all these famous shows like Mindhunter, which are based on behavioral sciences unit and how they put together sort of portrayals of serial killers and stuff, but it went back to all back to the thing with the principal, which is you have to know the other side, you have to know the player to know the cost. So basically, they were developing portraits of people they would negotiate with so they can know what to offer, what not to offer, where to put pressure and where to give rewards.

So ultimately, that just turned into the whole rest of his career where he worked for the CIA and the State Department, but it happened just all very organically by a job he almost took by accident, never a job he planned to stay at after he got out of law school. He ended up never practicing law, he’s a lawyer that never practiced law, and this goes to another principle of his which is, don’t get fixed on a particular outcome. He had this plan for Allstate, which is he was gonna work there for a few years until he got a job in a law firm, but his plans changed, and you have to be ready for your plans to change every step of the way, ’cause sometimes you get something better than you went for.

Brett McKay: Well, it relate to this idea of don’t get stuck to particular outcome, one of your father’s foundational principles is to care, but not that much. What did that look like in action for your father?

Rich Cohen: I always thought of him… When I got to college and started studying Eastern religions, the guy is a Buddhist man, but doesn’t even know it, which is he believes in detachment and approaching life like a game and realizing that none of this really matters. He would always say to me, in this world, we’re renters, all of us, no one owns. You’re gonna turn it all back in at the desk when it’s over. So basically, if you look at it that way, then you don’t become emotionally detached and you play loose and easy and you’re much more effective. What that look like was being able to walk away from a deal, giving a little bit more than maybe you wanted because in the long term it was better to give a little bit more. Changing your plan, not being bogged down by losses because none of it really mattered, it was a game. And this is why he’d say, “You can never negotiate for yourself, because when you negotiate for yourself, by definition, you’re gonna care too much or with your family, you care too much, and when you care too much, you screw it up every single time.”

Brett McKay: But your father, he was able to do this professionally, but then he had an instance in his life where he started to care too much, because he was negotiating for himself. And this happened, it was a legal battle over his really popular book that he wrote. What lessons did you take from that, from your father’s experience with that?

Rich Cohen: Well, looking at my father, in a sense, my father’s book was a self-help book. But it was a business book and a memoir, but it was a self-help book, and it helped a lot of people. But I realized, watching my father and knowing the story of other people who wrote books, the people who write self-help books are pretty much the people most in need of self-help, they’re really talking to themselves. ‘Cause my father would care too much, he’d get overly invested in battles that he thought concerned principles or justice. So the great thing about him, but also caused him to make mistakes. So with his book, his book came out and was this massive best seller, sold a million copies in a year or something. And back then, that was even more, ’cause they are fewer people in the country. And he got sued for plagiarism, which I knew was bullshit, because the stories he was sued for, a bunch of them were the things that actually happened to me, and everybody else knew it wasn’t true. Okay, but his publisher came and said, “Look, when you have a book that’s this successful, people come out of the woodwork and they sue you, and their nuisance lawsuits, and they expect you just to pay them off.” And it’s like the claims adjuster thing at Allstate, which is, it’s cheaper just to pay them off and move on, pay the ticket and move on, than get bogged down in a legal battle that’ll take you money, time, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.

But he was convinced that if he paid these people off, he was admitting in some way, or confessing to having taken their ideas, which wasn’t true, and he refused to do that, he refused to give in to these people. And instead, what he did is, he said, “My work pre-dates your work”, ’cause he’s already been doing this for 25 years when his book came out. And if you think ideas are the same, it means you stole them from me, and he counter-sued. And four years, five years, he spent more money on those lawsuits, ’cause there was two. One was in New York, one was in LA. So he needed three sets of lawyers, ’cause we were in Chicago. He spent more money on that than he ever made on the book, and he spent years of time when he should have been writing his second book. And in the end, the other side figured, “Well, he’s been saying he’s been teaching these ideas since he was at Allstate, when he was a kid. So all we have to do is find somebody who had been at Allstate with him, he won’t remember any of this, and we’ll prove that he didn’t have those ideas then.”

And they found this guy, and they asked him, the other side lawyers, if he remembers my father having these ideas. He goes, “Yes. In fact I still have his booklet.” And they said, “What booklet?” And he said, “I’ll show you.” And it was a workbook he’d created for training at Allstate, and it had like a lot of the stories in his book, from 20 years earlier. He’d just been recycling a lot of these stories that he’d written way back then. And the other side was sort of astonished. So ultimately, as soon as they found that booklet, they moved to settle and they had to pay my father. And they had paid him, I don’t know, like $50,000, and there was a big giant check. But in the end, it was a pyrrhic victory, which is, you win in that you win, but you lose, in that you spent 10 times more money than it would have cost to settle. And you spent a lot of your life and a lot of time, and a lot of anxiety fighting this thing. But this was again, another old Brooklyn thing, which is about bullies. He thought these people were bullies and they were trying to get his lunch money basically, and his attitude was, “If you give in to this bully, then other bullies will appear out of the woodwork and want everything else.

So you have to fight to the death and then nobody will mess with you again, ’cause they’ll think this guy’s nuts.” So it was like two principles of him came into contact and he went with the how to deal with bullies principle, which I think in retrospect was probably a mistake.

Brett McKay: Well, you also experienced this, you kind of became Captain Ahab for justice when you were in college. You had this creative writing teacher, he was just kind of this big jerk. And you told him about it and then your dad made this, “I gotta take care of it. I gotta stand up to this guy.”

Rich Cohen: ‘Cause again, it went to his idea of bullies and justice. So, I had this teacher in college that his philosophy was… I didn’t get a degree in any kind of creative writing or anything, I just took a creative writing class. And the teacher’s philosophy was, “I have to leave blood on the floor. I have to destroy all the ego of all these students.” And I got personally involved in hating this guy, and he hated me. And I wrote a poem that cursed him out, and he sort of went after me, and it was a whole ugly thing. And at the end of the year, the guy gave me a B in the class, because he knew if he gave me a B I couldn’t really complain. Because I thought what he was doing was horrible, the way he was treating these kids in this class. And when I came home during Christmas, ’cause it was first semester of my senior in college, I was telling everybody about this thing. And my father did not care. I could not even engage him. And finally, he said, “Listen, if I sit down for 10 minutes and listen to you finally, will you then shut up and leave me alone?” And I said, “Yes.” And within three minutes I could see his eyes light up, I could see him get angry, and I’m like, “Oh, I made a mistake.” It’s like I summoned Beetlejuice.

And by the end, he was so infuriated at this teacher that he made this his cause. And he went to war with the school and this teacher to the point where I said to him, “Would you stop? I’ve moved on. Man, I’m now a second semester senior, I’m looking for a job.” He said, “You might have moved on, but I haven’t.” I’m like, “What’s the point of this?” He goes, “It’s not for you, it’s for the next kid who’s gonna be destroyed by this person. I’m protecting the next kid.” And so he had all these demands, and actually I found out later that he was still going down to New Orleans, I went to Tulane, to fight with the English Department three years after I graduated. And later on, he was in the hospital, he had a heart incident. He wouldn’t call it a heart attack, but basically his heart stopped working. And he had very long surgery, he thought he was gonna die. And I sorta thought, “I wonder if the stress from this stupid Tulane thing that I got him into is causing this.” And I said to him, “You know, you gotta drop this now.” And he said, “I will never drop it, and your older brother has been briefed. And if I should fall in this battle, he will pick up the standard and continue the fight.” It was nuts.

And finally, when the whole thing was finally settled, and it was, again, it was like he got… He won, but he didn’t get anything, it didn’t amount to anything. And I said, “So do you see now that it was like a big mistake and it was a waste of time and you basically lost?” And he said, “No, I won.” And I said, “How do you figure that?” He goes, “‘Cause the next time that teacher is about to destroy a kid, suddenly the doubt will pop into his head, “Maybe this one has a crazy father too,” and as a result, that kid will be saved from being crushed.” So, he didn’t like the idea of people’s creativity being crushed by authority, and that’s what he saw in the school. But that was again another instance of over-caring.

Brett McKay: But he was playing some game theory there, right? He was thinking, “That’s the whole thing, I want the person to think that I’m crazy or there could be another crazy person, this is gonna cause anything twice.”

Rich Cohen: Right. But it was like, to me, a really great battle to play with the Russians, but this was like, “You pick your battles.” This was a small thing, ultimately. But who knows, maybe it did save a bunch of kids from having this terrible experience and never wanting to open their mouth to say anything again because they were afraid of how it would be received.

Brett McKay: Okay. So, I think the takeaways from these stories are, one, “Choose your battles” is the big one. “But then also try not to negotiate for yourself, ’cause that’ll just get you into trouble. And if you have to negotiate for yourself, you gotta try to be detached. Pretend… And the only tip I’ve heard is, “Pretend like you’re negotiating for someone else when you’re negotiating for yourself.” And this principle of “Caring but not caring,” I think about this a lot. And I’ve been trying to figure it out and strike that balance. And I haven’t figured it out, I’m constantly striving for it. But it’s a good reminder to care, but not too much. So another one of your father’s principles was, “It’s not the what, but the how.” So, what did he mean by that? And how did you see that play out?

Rich Cohen:Well, he would always use a restaurant as an example, which is “It’s not what the food that they’re serving here that is bringing you in, it’s how they’re delivering it, how they’re treating you, what the experience is like.” And he was very big about treating people with a lot of dignity. So, here’s a trick he taught me recently. This is after the book. He said, “If you’re running late to a meeting, and due no fault to your own, traffic, whatever, you’re late. People receive that as great disrespect, you know, ’cause you don’t care about their time.” He said, “If you walk in 10 minutes late, apologize profusely and say, “I’m sorry, I got stuck in traffic, I’m 30 minutes late.”” And they’ll go, “Oh no, no, you’re only 10 minutes late.” And instantly change the dynamic of them being mad at you, but then sort of backing you up and apologizing. Another little thing he taught me, this is unrelated but I always think it’s so funny is, he meets all these people, and he doesn’t remember a lot of people, he’s met so many people. And when they come up and they talk to him, he explained this to me once like they know him.

He says, “Are you still living in the same place?” He’s like, “If you ask about their wife, maybe their wife died. If you ask about their husband, maybe they got divorced. If you ask about their job, maybe they got fired. But if you ask if they’re still living in the same place, well, either they are and they’re so glad you remembered their place, or they moved and that’s a story they can tell you.” So, it’s a little trick of human interaction. And a good example of the what versus the how is, we used to always go to this really bad restaurant in our town. And finally, I said to him, “Why do we go to this bad restaurant even though we all hate the food?” He said, “Because they always give us the booth.” So, that was the how over the what. So he really talked about how you treated people and creating the experience of how you were treating them, as opposed to just what you were offering.

Brett McKay: Well, you also learned this when you’re buying your first car. You figured out that, okay, the perfect car for you is this Honda Civic, 70,000 miles. And then you found it. And you go to look at it, and your dad’s like, “No, because it’s not the what but the how.”

Rich Cohen:Well, the story is, so we went, we finally find this car, I didn’t want that car, specifically. He made a long list, this is his information where he rated each possible car I could buy with in 20 categories. And based on that score, ’cause I needed a used car that was a certain price. I needed to get a Honda Civic with less than 70,000 miles. And we found it, and I was excited that we found it. And he’s like, “I don’t think you should get this car.” I’m like, “What? This is your car. How can you say that? This meets every criteria.” He said, “Did you see all that writing?” And the previous owner, on the door it said, “Barry.” On the passenger side door, it said “Chuck,” like in calligraphy writing. And on the door it said, “Barry.” On the other door, it said, “Bobby.” And on the hood, it said, “Chuck.” And he said, “Did you see all that writing?” And I said, “So what? We’ll have it painted over.” He goes, “You’re missing the point. A schmuck owned this car.” And to me, that was the what versus the how, which is, “It’s not just what the car is, but it was how the car was treated, who was driving it,” blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.

But it really made an impression on me. And as most things he did, it was very funny to the point that I remembered it all my life. And look, I ended up with a Dodge Daytona that probably wasn’t any better. He also made a big list like that to get the best perfect dog for our family. And after we filled out like 50 different check marks, we ended up with a beagle, the most average, generic dog you can get. So, his system did have its limits.

Brett McKay: So, when we talk about these principles that your dad extracted from his life that he applied to his career as a negotiator, when you look back at your father’s life, what was the big idea that was guiding him?

Rich Cohen: The big idea is, “Approach life like a game, ’cause that’s what it is.” And that in the end, nothing, none of this stuff will matter in the end. In the end, all that will matter is your relationships and how you treated people. And he’d always say when I came to him with a problem that I was obsessed about, “It’s just a walnut in the batter of life, it’s just a blip on the radar screen of eternity.” And that was his message, which is, “It just doesn’t matter that much. And that knowledge, while it could scare you, should also give you the kind of freedom to act and do what you want and what you can in the game of life.”

Brett McKay: Well, Rich, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go and learn more about the book and your work?

Rich Cohen: I have a website, authorrichcohen.com, and I’m on Twitter, Rich Cohen 2003. 2003, because that’s the year I peaked. And those are probably the best places. Also, the publisher, McMillan, has a site for me, and Amazon for the book.

Brett McKay:: Fantastic. Well, Rich Cohen, thanks for the time. It’s been a pleasure.

Rich Cohen: Yeah, really fun. Thank you.

Brett McKay: My guest here was Rich Cohen. He’s the author of the book, The Adventures of Herbie Cohen: World’s Greatest Negotiator. It’s available on Amazon.com and book stores everywhere. You can find more information about Rich’s work at his website, authorrichcohen.com. Also check at our show notes today, aom.is/herbie, where you find links to resources where we delve deeper in this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM podcast. Make sure check out our website at artofmanliness.com where you find our podcast archives, as well as thousands of articles. You know, there’s about pretty much anything you’d think of. And if you like to enjoy ad free episodes of The AOM podcast, you can do so on Stitcher Premium. Head over to stitcherpremium.com, sign up, use code “MANLINESS” at check out for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the stitcher app on Android or IOS, and you start enjoying add free episodes of The AOM podcast. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on Apple podcast or Spotify, it helps us a lot, and if you have done that already, thank you, please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you think will get something out of it. As always, thanks for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay reminding you to not only listen to The AOM podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.