While recently working on a side project where I needed to think through what it meant to be a good citizen, I found to my dismay that my own conception of citizenship was quite hazy. I couldn’t remember talking about it very much in school growing up. Sure, I think I watched a cartoon about how a bill becomes a law, and got some lessons about U.S. history and the different branches of government. But I don’t recall the connections that were made between such facts, or how a citizen was supposed to engage with them — what it meant not only to live in this country, but to contribute to it.

So too, I found there were few modern resources on the subject of good citizenship. Civics, while it would seem to be an integral part of every person’s education, seems to be something we’re just supposed to pick up somehow as we get older. Unfortunately, that doesn’t often happen, and as a result, most people have a view of citizenship that’s just as hazy as mine — or more accurately, just as incomplete.

I eventually came to find some of the best insights about citizenship in my collection of old Boy Scout manuals, which always included a section about what it meant for young and grown men alike to participate in a democracy.

Especially instructive was a manual released in 1953 dedicated solely to explaining the Citizenship Badge (there was a whole series of short, separate books available at the time for each respective merit badge). The Citizenship manual explained that “citizen” was another word for “member,” that every young man was a member of a town, a state, and the nation, and that membership in these bodies, just like membership in any other organization, was a two-way street — it came with both benefits and duties.

When citizenship is mentioned at all today, it’s usually in the context of rights: “I have the right to do this!” “I have the right to do that!”

But as the manual points out, these privileges come with accompanying obligations [emphasis mine]:

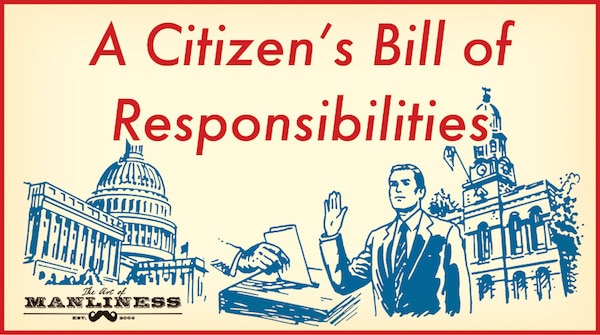

“A good citizen has a ‘Bill of Responsibilities’ to live up to as well as a Bill of Rights to live under.”

A Bill of Responsibilities. You may never have thought about this concept, but such a thing inarguably exists. Membership in any group confers certain advantages, but they are contingent on each member following the group’s rules, actively participating, and contributing to the group’s health and strength.

While the privileges of the Bill of Rights are explicitly spelled out, the obligations of the Bill of Responsibilities are implicitly charged. The latter are thus easy to forget, often subsumed by an exclusive focus on the former.

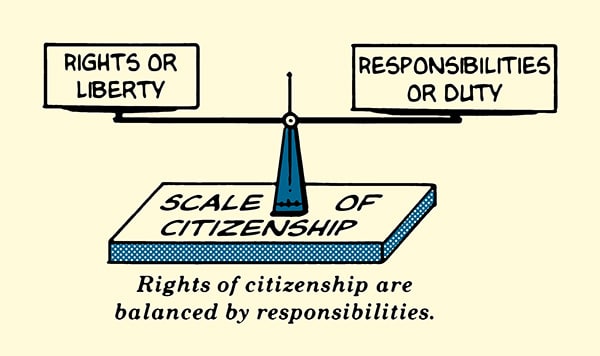

Yet the continued existence of rights is premised on the fulfillment of their reciprocal responsibilities. Democracy can only flourish when people are able to govern themselves. In the absence of such self-governance, without the collective willingness to live virtuously, participate intelligently in the public sphere, perpetuate the greatest good for the greatest number, and serve each other and our communities, more and more regulations and laws must be passed to compel behavior and maintain order, curtailing liberty. Freedom paradoxically cannot endure without constraints.

Democracy is thus a two-way partnership: citizens receive certain rights, services, and protections from the government, and in turn offer their money, time, knowledge, and commitment towards maintaining these privileges. Individual rights must always be matched with individual responsibilities; one cannot hope to have a healthy democracy if citizens are solely focused on what they can get, to the exclusion of what they can give.

I think it is useful, then, to pause occasionally to discuss the implicit obligations of citizenship in a more direct way — to reflect on how we measure up in our duties. As the Scout manual puts it: “the ‘Bill of Responsibilities’ is a sort of yardstick of citizenship.”

Below you’ll find an attempt to spell out some of the responsibilities that are attendant to the rights contained in our national, state, and local laws (including the Constitution, statutes, and judicial opinions); they can of course be added to, and vigorously debated.

1. The right to a fair trial./The responsibility to serve willingly on a jury when called.

It’s hard not to moan and groan when you’re called up to jury service. It’s an inconvenience to your life, and sometimes a detriment to your paycheck as well. But the factors that make jury service especially inconvenient — a steady job, being a business owner, having children — are also things which speak to the fact that you’re an engaged member of the community, and thus a valuable juror. When these kinds of engaged citizens try to duck their duty, jury pools are left only with those who aren’t “clever” enough to find an out, the unemployed, and the retired. This hardly makes for a jury of one’s peers.

Were you to be accused of a crime, you’d want a diverse, savvy jury hearing your case; give other people the same privilege by willingly serving when called to do so.

2. The right to free (and/or government supported) schooling./The responsibility to take full advantage of one’s education.

To my shame, I had never thought of education as being a two-way street until I read this in the Boy Scout Citizenship manual:

“As a citizen of the United States, you have the right to a free education in the public schools; but you also have the responsibility to do your best to take the fullest possible advantage of that educational opportunity in order to prepare yourself for a life of useful service to your fellow citizens.”

While we often think we have the right to goof off in school, that it only affects ourselves, if you’re attending a publicly funded institution or using publicly funded loans to finance your education, you’re goofing off on someone else’s dime. Factory workers and doctors, teachers and firefighters, are laboring 40-80 hours a week, and giving up chunks of their paychecks so you can play Fallout 4 and flunk your biology class.

If you’re a student, make good on your fellow citizens’ investment in you, by taking full advantage of your education and equipping yourself to leave school able to strengthen your community and country.

3. The right to protection of life and liberty./The responsibility to stay ready to defend that right and the willingness to serve when called.

Americans today enjoy the privilege of being protected by a professional, all-volunteer military force. But should another large-scale crisis, like the past world wars, emerge, the draft would be re-instituted. Citizens not only have the responsibility of answering such a summons when in force, and also staying ever ready to serve during times of peace. To the best of their ability, citizens should prepare their bodies and minds for a call to defend their country. The Founders imagined every man as a citizen-soldier.

4. The right to enjoy natural resources./The responsibility to preserve and conserve public parks and lands.

Our national parks are some of our greatest treasures, and our local parks some of our most appreciated retreats. Government provides access to these wild and bucolic preserves; citizens are charged with following “leave no trace” principles, practicing fire safety, and keeping them clean and pristine.

5. The right to welfare assistance./The responsibility to be as self-supporting as possible.

The government’s aid programs are designed to help those who have no other options for assistance — as a safety net when all else fails. Citizens have the responsibility of only availing themselves of such programs out of true and honest need, and making a best faith effort to decrease the chances of falling into that fix: working when possible, exercising financial prudence, and maintaining healthy habits. No one is ever entirely self-sufficient, but striving towards that goal ensures that welfare goes to those who really need it, lightens the burden on the system, and frees funds to be put towards other important projects, thus strengthening the nation.

6. The right to use public libraries, roads, transportation, parks, police/fire services, etc./The responsibility to pay the taxes which support such services.

Nobody likes paying taxes. But nearly all of us like to drive all over town and across the country on paved roads, eat non-contaminated food, and read reams of books for free. Nearly all of us want to know that the police and fire department would come to our aid in an emergency. All of these services, and many more, rely on tax money to exist. If you take from the pot, you also have to put into it.

This isn’t to say that citizens don’t have the right to opinions on how they should be taxed, and how their money should be used. As the Boy Scout manual advises, every citizen has the responsibility to “watch whether these funds are spent wisely or not.”

It can be galling to see how much government money is wasted and misappropriated, but the recourse to this outrage is to vote for politicians and policies that will change the system, not to stop paying taxes until they meet personal standards. Otherwise, one’s position is akin to someone who justifies stealing a business’ services because the individual disagrees with their business model; e.g., sneaking into a movie without paying because you think they charge too much for tickets.

7. The right to free speech and protest./The responsibility to offer informed opinions and constructive criticism, and to uphold the free speech of others.

The right to free speech, and its related rights to assemble peaceably and petition the government for a redress of grievances, are some of our most cherished American privileges. As long as we don’t unfairly hurt others, or incite violence or treason, we can say whatever it is we want. As Citizenship celebrates:

“The government cannot censor our letters, burn our books, cut our radio programs off the air, or otherwise hamper the free expression of our thoughts, providing we respect the rights of others. In America there are no ‘thought police’ to control what we read or listen to…We have the right to gather together when and where we please…Even when we are criticizing our government, we are entitled to police protection.”

While we have the right to say nearly anything we want, that doesn’t mean we should; we also have the responsibility to offer speech that is well-informed and well-reasoned.

Citizens should know how government works so as not to call for one of its branches to make a change or take an action that is not actually within the purview of its powers. Citizens should also not just complain, but offer constructive solutions, “avoid[ing] any criticism unless he can suggest an improvement.” We have the responsibility of actively striving towards the change we want to see — of putting our skin in the game and working through community groups, churches, non-profits, and elections to alter the landscape and address injustices.

At the same time, citizens should fervently uphold the right to free speech for others, including those — especially those — with whom they disagree. Too often there is a tendency to support free speech when someone says something with which we concur, only to throw it out the window when they say something that offends our sensibilities. But the right of free speech can only be preserved when it is applied equally, even to words the majority find despicable. The government is not to act as the thought police, and neither should its citizenry.

Finally, the right to speak freely comes with the responsibility to listen earnestly. It requires, as the Citizenship manual puts it, “keeping an open mind, trying to understand [others’] viewpoints, considering the minority opinion on a question and cooperating with the majority opinion, once it is accepted.”

8. The right to equality under the law./The responsibility to stand for the equal rights and opportunities of others.

A good citizen doesn’t just enjoy his own access to equal opportunities, his own equal protection under the law — he is distressed by the encroachment and violation of these rights for others. This not only applies to the right of free speech, but to other rights like the freedom of religion; if you want to enjoy the right to worship as you please, you’re responsible for supporting the right of others to worship as they see fit.

As the handbook advises, a good citizen wants everyone to share the same constitutional privileges he does, and “Stands for equal rights to opportunities for all, for fair play regardless of anyone’s race, religion, nationality, social position or way of earning a living.”

9. The right to bear arms./The responsibility to train yourself in the safe and effective use of your firearm.

The Second Amendment enshrines Americans’ right to equip themselves with one of the most powerful tools on earth — a tool which can take another’s life. With great power, comes great responsibility, and those who choose to exercise their right to bear arms, also have the responsibility of becoming versed in how to use their firearms safely and ably.

10. The right to vote./The responsibility to be fully informed as to candidates, issues, and parties.

While there are no longer any explicit barriers to voting (besides age), an implicit barrier should remain: knowledge of what one is casting his ballot for. Knowledge that runs deeper than headlines and soundbites, and encompasses a good understanding of both sides of an issue, and the positions, policies, and character of political candidates.

The simple act of casting a vote in and of itself is often seen as the ultimate expression of citizenship; but voting in ignorance is no better — in fact is often worse — than not voting at all. As the Scout manual admonishes, “Be a thinking citizen, not a thoughtless one.”

11. The right to publish anything short of sedition and slander./The responsibility to vet and examine published information.

Just as Americans have the right to say nearly anything they please, we also have the right to put down on paper (physical or digital) almost anything we’d like. The freedom of the press ensures that individuals and media companies can publish their thoughts, opinions, and reports without government interference. But the readers of these publications in turn have a responsibility for evaluating the validity and accuracy of the information that is disseminated — calling out errors and refusing to support purveyors of lies and misinformation.

In the digital age, when anyone and everyone is now able to become a “publisher” and exercise the freedom of the “press,” the responsibility to vet and filter information has become more important than ever.

12. The right to happiness./The responsibility to contribute to that happiness by living virtuously.

Everyone loves that the Declaration of Independence consecrates “the pursuit of happiness” as an unalienable right. Yet few understand how the Founders defined happiness. It was not mere personal pleasure or a good feeling; rather, they conceived of happiness the way the ancient Greeks did: as virtuous excellence.

The Founders believed that the success of the republican experiment they were setting forth was contingent on its citizens living lives of industry, honor, frugality, humility, and justice. If citizens wished to enjoy their rights, they needed to live right; private happiness, or virtue, led to public excellence — an environment in which individuals had the liberty, protection, and structure to truly flourish.

13. The right to effective, intelligent, just representation by elected officials./The responsibility to be an active, engaged, informed citizen.

Everyone wants to live under a fair, honest, effective, efficient government. But few want the obligation of helping to produce that good government. They want virtuous politicians, but live morally lax lives themselves. They want to be heard, but don’t listen. They want to be served, but don’t want to serve. They want to get, but not give.

They don’t understand why government seems so inept…yet people invariably get exactly the leaders they deserve.

There is no protection without participation, no freedom without duty, no liberty without constraint.

If citizens wish to fully enjoy living under their rights, they must fully live up to their responsibilities.