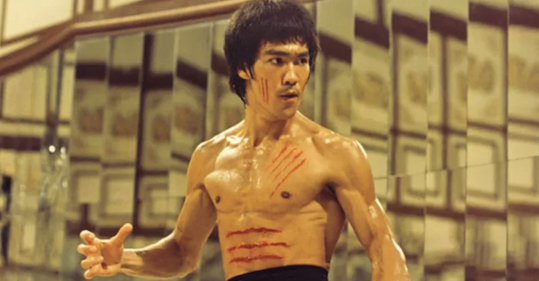

Many people know Bruce Lee as a martial artist and film star. But he was also a philosopher, who articulated principles that apply beyond engaging in artful combat, to grappling with life itself.

Shannon Lee, daughter of Bruce Lee, caretaker of his legacy, and author of Be Water, My Friend: The Teachings of Bruce Lee, unpacks those principles on today’s show. We begin our conversation with what Shannon remembers of her late father, and how she discovered the power of his philosophy after sinking into a depression following the death of her brother, Brandon Lee. We then dive into some of the sources of Bruce Lee’s philosophy, his reading habits, and what books he kept in his extensive library. Shannon shares the story behind how her father first started formulating his ideas around becoming like water, how he engaged in forms of moving meditation, and what you can learn from his journaling practice. We end our conversation with the resilient, proactive way Bruce Lee responded to a potentially crippling back injury.

Great inspiration in this show on what should be every man’s ideal: the combination of contemplation and action.

If reading this in an email, click the title of the post to listen to the show.

Show Highlights

- Shannon’s memories of her late father

- What catalyzed Shannon’s interest in her father’s philosophy?

- What was the big picture aim of Bruce’s philosophy?

- Bruce’s reading life and philosophy library

- What does it mean to “be water”?

- How did Bruce empty his cup? What was his meditation practice like?

- The fights — literal and metaphorical — over Bruce’s martial arts system

- Turning the abstract into the concrete

- Bruce’s journaling practice

- How Bruce responded to bad back injury that laid him up for a year

Resources/Articles/People Mentioned in Podcast

- How to Throw Bruce Lee’s 1-Inch Punch

- The Libraries of Famous Men: Bruce Lee

- The Life of a Dragon

- Brandon Lee

- Alan Watts

- Be Water

- Meditation for Fidgety Skeptics

- A Man’s Guide to the Martial Arts

- Jeet Kune Do

- The Power of Moral Reminders

- Action Over Feelings

Connect With Shannon

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

If you appreciate the full text transcript, please consider donating to AoM. It will help cover the costs of transcription and allow other to enjoy it. Thank you!

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. Many people know Bruce Lee as a martial artist and film star, but he was also a philosopher who articulated principles that apply beyond engaging in artful combat to grappling with life itself. Shannon Lee, daughter of Bruce Lee, caretaker of his legacy, and the author of “Be Water, My Friend: The Teachings of Bruce Lee” unpacks those principles on today’s show. We begin our conversation with what Shannon remembers of her late father, and how she discovered the power of his philosophy after sinking into a depression following the death of her brother Brandon Lee.

We then dive into some of the sources of Bruce Lee’s philosophy, his reading habits, and what books he kept in his extensive library. Shannon then shares the story behind how her father first started formulating his ideas around becoming like water, how we engaged in forms of moving meditation, and what you can learn from his journaling practice. We end our conversation with the resilient proactive way richly responded to a potentially crippling back injury. There’s a lot of great inspiration in this show on what should be every man’s ideal: The combination of contemplation and action. After it’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/leephilosophy. Shannon joins me now via clearcast.io. Shannon Lee, welcome to the show.

Shannon Lee: Thank you. My pleasure to be here.

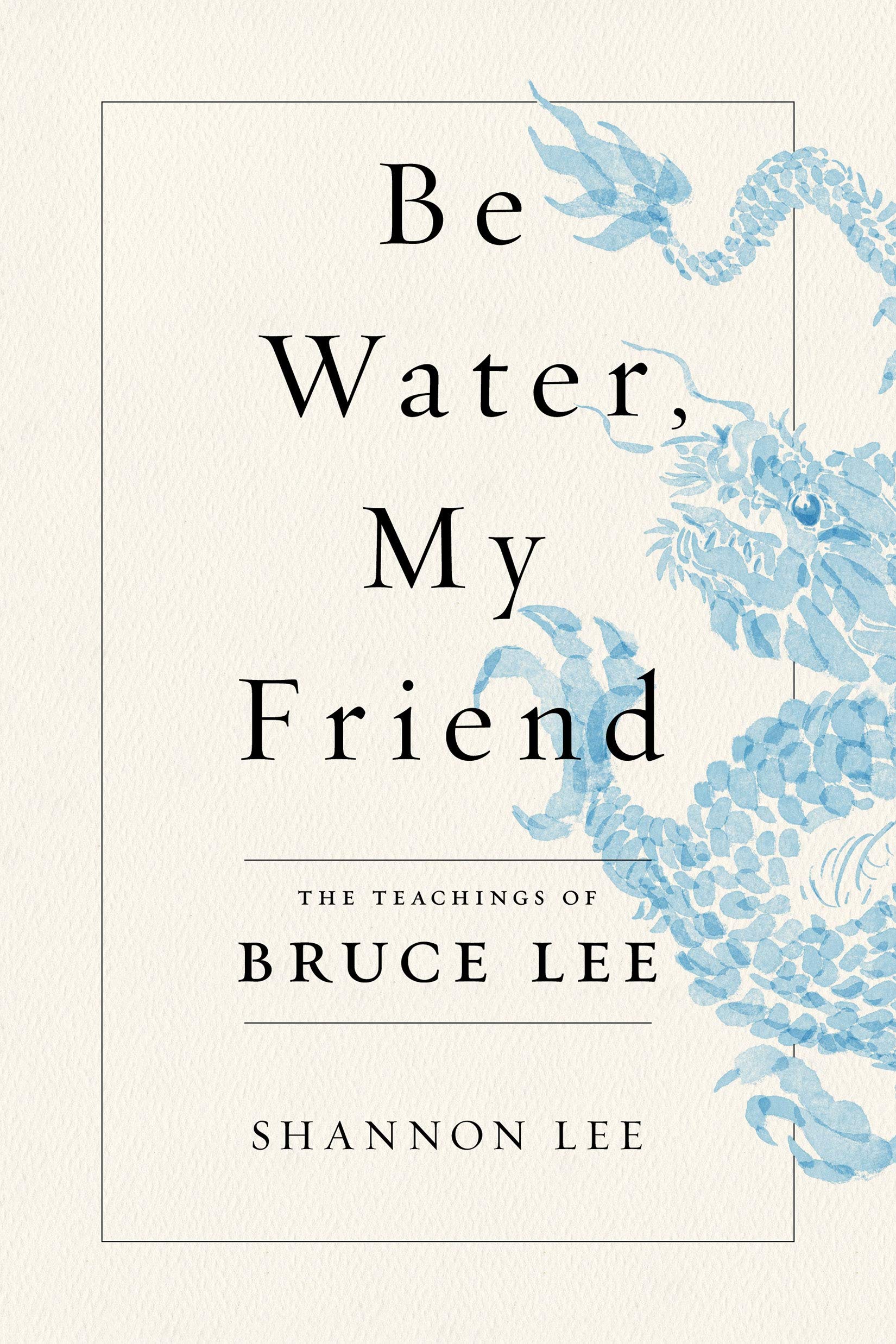

Brett McKay: So you are the daughter of Bruce Lee, and you also are in charge of your father’s legacy. You manage what you call “the business of Bruce Lee”, and recently, I think it was last year, you put out a book called “Be Water, My Friend”, which is… You basically synthesized your father’s philosophy. A lot of people don’t realize is that Bruce Lee was a philosopher. Synthesized his philosophy, but also showed practical applications of how to put that into practice. And I’m hoping we can, in this interview, discussion, talk about the sources of your father’s philosophy, what it looked like big picture, and then how we can apply that. But before we do, let’s get personal. I’m sure you get asked this question all the time, but you were four years old when your father died, how much do you remember of your father?

Shannon Lee: You know, I’m sure anyone thinking back to what they remember when they were four, and I know there are some people who remember every single thing, but I think that’s fairly rare. My memories are quite limited. I don’t have those long-form visual/audio memories, where I’ll say, “Oh, I remember when he walked into the room and then he said this, and I… “, all that kind of thing. But I’ll tell you, and I talk about this in the book, and thank you by the way, for having me on the podcast, to talk about the book. The thing I really remember very vividly is the feeling of him. And it took me a really, really long time to understand that that was a memory. I used to think I was just a little bit insane, ’cause I was like, “God, I feel like I really know this person. I feel like I know this person intimately”, in a strange way. And I used to just think, “Well, gosh, that just must be some strange longing that I have or something, but it is so visceral for me.” And it wasn’t until I talked to another friend of mine who had lost their father at a young age, and I was describing the sensation, and he said, “Oh yeah, I have those memories too”, and I was like, “Memories! These are memories.” [chuckle]

And so I have to say, even though I was very, very young… And it makes sense, right? When I start thinking about it as a child, especially a toddler, before you’re even able to speak you’re feeling. You’re just feeling everything around you all the time and taking it in. And so I do remember things like going to visit him on set. I remember our house in Hong Kong, my memories really start in Hong Kong, we moved there when I was three. And I remember though what he felt like, his energy, his just kinetic, charismatic, sparkly, intense presence. And that is something that I am so grateful for.

Brett McKay: Well, I’m hoping in our conversation we can let our listeners get a sense of that kinetic vitality that your father had. You describe in the book, in your teenage years and in your early part of your 20s, you didn’t think too much about your father’s philosophy, like cerebrally, but then you had this moment in your early adulthood where you went to a dark place. You had a crisis, despair, depression. And it was in this moment, like your father’s philosophy kinda hit you in a very profound way, almost as if he was speaking to you from the beyond, and that led you to dig deep into his philosophy, also making your life’s work overseeing his legacy. Can you walk us through that experience and what led up to that moment?

Shannon Lee: Sure. So, of course, being raised in my family as I was, I was familiar with some of my father’s philosophy, in particular the more famous ones, like “Be water, my friend”, or “using no way as way”, “having no limitation as limitation”, and those types of things. But, as you say, I had never really delved deep into it or looked into it, I just kind of knew it because it was just part of my culture growing up. But then right before my 24th birthday, my brother was killed in an accident on a film set. And that was extremely traumatic, and it just plunged me into this really painful dark place, where I didn’t know what to think. I had all of these horrible feelings that I didn’t know what to do with, and I didn’t know how to make sense of it, if that’s even possible.

I didn’t know how I was supposed to keep going on with my life. The world became very nonsensical, and I’m sure anyone who’s experienced death closely knows what I’m talking about, when you’re just sort of in bewilderment that the world is still going on around you like everything’s fine, when you yourself are clearly not fine. And it’s really hard to know what to do with yourself. And for me it really set off this book-end experience, my father having died when I was four and then my brother dying right before my 24th birthday, so 20 years apart. As I healed through that process I started to see like, “Oh, I’ve been mildly depressed my whole life”, it’s just that with this sudden immense tragedy I was just plummeted into such a deep well of painful depression.

And you go through a funeral, you go through memorial services, you have some time for a little while where you’re just so bereft with grief, and then you kinda have to keep living your life. And so on the outside, I was going through the motions of living my life, but on the inside I was in an extreme amount of pain. And when I would have my quiet moments, and I talk in the book about driving in my car around LA, which we do a lot in LA, and just crying as I’m driving. And then I would arrive some place and I’d sort of wipe off my face and throw a smile on and hop out of the car and go about my life, and that’s not really living. That’s two separate planes of existence, which is a really hard thing to maintain.

And I went on this way for a couple of years, and then just sort of by happenstance I was given photocopies of all of my father’s writings. [chuckle] My mom was working with someone on a series of books and they had made copies of all of his writings in order to go through them, and they handed them to me and said “We made you a copy, we thought maybe you would like to see these.”

And, dating myself here, but it was like three phone books worth of papers of his writings, and I just started flipping through them. And as you can imagine, a lot of them are around martial arts and technique and that sort of thing, but so many of them were about philosophy and his thoughts on life, and there were creative writing. There were all sorts of things in there, it was like a treasure trove. And as you say, I came across this one quote that I had never heard before, not having been a student of his writings that I am now, and I just had this sudden response as if suddenly it’s like there was a little vision or a little crack that opened up and some light got in. And all of a sudden I was like… It just hit me square in the chest, and I just thought, “Oh my gosh”.

There was something about this quote that it just said to me “You can be okay. You’ve gotta work for it, but there is a way to know yourself and heal yourself and move forward.” And that quote, which sometimes I butcher, and sometimes I don’t, we’ll see what happens, is “The medicine for my suffering, I had within me from the very beginning, but I did not take it. My ailment came from within myself, but I did not observe it until this moment. And now I see that I will never find the light unless, like the candle, I am my own fuel.”

And there was just something about that that said, “You’re suffering, the way that you are suffering, is coming from within yourself, and you’ve got to seek the cure for that. You’ve got to start observing that pain and really starting to question it and really starting to seek a way through it, not to ignore it, not to deny it, but to really let it in and explore it.” And I didn’t have those amazing sensical thoughts in that moment, it’s just that the words hit me and I just thought, “Oh, the medicine for my suffering, I have the medicine for my suffering”, then I was like, “Okay, what is that?” [chuckle] And I just kept reading and reading and reading, and I found that the medicine was in the words, and it was in me attempting to apply the words.

Brett McKay: So this is a question I’m sure it’s gonna be hard to answer. So your father was a philosopher besides a martial artist, but his philosophy and his martial arts was intertwined. And the other thing about your father that I took away from your book is that he wasn’t a dogmatist. And so his philosophy it was open. And so you really couldn’t put a container around it, but if you were to do that, so we can grasp it a little bit, what would you call his philosophy? Like big picture, what was the aim of Bruce Lee’s philosophy?

Shannon Lee: To me, his philosophy is about self-actualization, which means essentially making a reality of one’s truest self. Or, said another way, fulfilling your potential to the best of your ability. And for him that meant as a martial artist, but also as a human being. And I think he said “Everything that I’ve learned in life I’ve learned from doing martial arts.” And then later in his life, he said, “I’m a martial artist by choice, I’m an actor by profession, but what I’m really hoping to be is an artist of life.” And so I think philosophy and sort of one good way to test philosophy is, “Is it applicable across experience?”

And the fact that it was applicable to his experience of martial arts as well as his experience of life, says to me that it is extremely useful philosophy. And what it means to self-actualize as a martial artist is one aspect, what it means to self-actualize as a human being is another. And I think if we step into the broader one, which is to actualize as a human being, then we also will actualize as a martial artist, because we’re attempting to fulfill our potential in every possible human way.

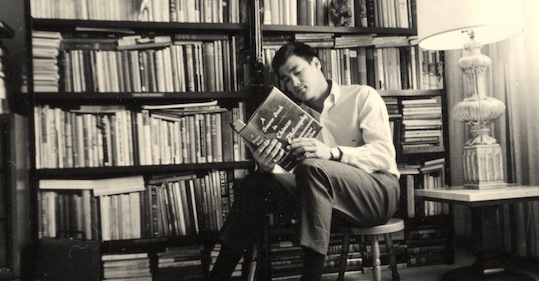

Brett McKay: Alright, so self-actualization, and I’m hoping we can get into the details of what that looked like, but before we do let’s talk about the sources of your father’s philosophy. I think something that a lot of people don’t realize that your father was a student of philosophy, he literally studied philosophy in college, and then throughout his life after college he continued to… He was a voracious reader, read all sorts of books, from books about boxing and martial arts to books about positive thinking, but also those philosophical really deep texts. Based on looking at your father’s work, do you have an idea of some of the sources of his philosophy, both Eastern and Western? And then maybe we can talk about his library a bit too, which I think some people would be interested in that as well.

Shannon Lee: For sure. My father was extremely self-educated and he believed in prescriptive reading, so reading that he took upon himself in order to learn something that he wanted to know. And as you say, he studied philosophy in college, he didn’t graduate, but he went to the University of Washington and studied philosophy for a couple years. And the funny thing is, everyone thought, “Well, this is weird, why is he studying philosophy?” [chuckle] They thought he would go into physical education or something having to do with physicality, because he was so active and physical and so interested in how to move his body and all that sort of thing.

But he was working with a guidance counselor at college to help him choose his classes, and his guidance counselor said to him, “You know, you’re really inquisitive”. My dad was one of those guys who would just ask questions all the time. “Well, why this? And what about this? And what does this mean? And what do you mean by this? And why should I do that? And what do you think about that?” And he was just extremely inquisitive, and his guidance counselor said, “You know, you’re so curious and you ask so many questions”. He said, “I really think you would enjoy taking a philosophy course, because philosophy is about why we do what we do and what we are living for, and why we are living for it.” And so my dad thought that was interesting, and so he signed up for some classes, and he immediately fell in love with philosophy. And he really started at that time to formulate this notion that he really needed to combine philosophy with martial arts, because it would explain the why of movement for him.

And that that was just as important in terms of learning and nutrition in martial arts as technique. And in fact, maybe in some ways more important, because it would give technique meaning. And so, it’s funny ’cause I’m sitting here in my office and I’m looking right now at all of the boxes and boxes and boxes of my father’s books that we have right now, and just… He had thousands of books, and they are underlined and annotated, and maybe not every single one, but a good majority of them. And he was very influenced by Eastern philosophy, in particular the Tao Te Ching, and he read up quite a bit on the different Eastern philosophical schools, like Confucianism and Daoism and Buddhism, and different aspects of that he was very interested in. He also read Alan Watts and Joseph Campbell and Krishnamurti. Krishnamurti and Alan Watts were two of his favorites.

And later in life, he, as you mentioned, went more into also self-help books and anything that sort of talked about like “These are some of the thoughts around why we live, and then these are some of the tools about how to live a better and better life.” And the funny thing is, is that when my mom, who’s five years younger than my dad, first laid eyes on my dad, it was at her high school. He had come to lecture on Eastern Philosophy at her high school, to the high school philosophy class. And she didn’t meet him at that time, but she saw him in the hallways and she said all the girls were like, “Who is that cute guy on campus?” [chuckle] So my father, anything that he undertook, he undertook it to the very best of his ability, and he really wanted to do it well. So if philosophy was his jam then he was going to dive fully into it and immerse himself.

Brett McKay: That was one thing that impressed me about your father and his reading, and his philosophy too, is that it wasn’t just theoretical for him, he always tried to put it into action. It wasn’t just contemplation. Like, he did that but that it was also oriented towards action as well. He didn’t just read Norman Vincent Peale, he actually did what the suggestions are in that book.

Shannon Lee: Totally. Totally, totally, totally, totally. And that’s the thing that I really try to get across in my book and about my father when I talk about him, which is he didn’t just espouse philosophy, he tried to live philosophy. And he himself had a quote that said, “Philosophy can be the disease for which it pretends to be the cure.” So, I think nowadays a lot of people can go around saying great quotes or posting great quotes, or they have a lot of jargon, but are they applying it? Are they really attempting to live through those words, or does it just sound good?

Brett McKay: Well, let’s dig into the details of your father’s philosophy and how we can put it into action. And I’m sure everyone has likely read or seen that YouTube video of Bruce Lee talking about his idea of “Be Water.” Do we know when he first started developing this concept?

Shannon Lee: Yeah. So, he had his big revelation about being like water when he was 17, so, early. He had this experience where he was in his martial arts class with Ip Man, and he was facing off with an opponent and he just kept getting really aggressive and trying to win. And Ip Man kept trying to say to him, “Stop trying to enforce a strategy, get out of your head, you have to follow your opponent’s movements, you have to be more fluid”, all this kind of stuff, and “You need to have more gentleness”, and my dad kept trying to understand what he was saying, but being a rowdy teen who just wanted to win, he just kept getting in his head trying to win win win at all costs. And finally Ip Man said, “Stop, go home. Think about what I said, don’t come back for a week.” And my dad was like, “What?” [chuckle] For him, martial arts was his life, he was absolutely in love with it, he was practicing it all the time, and he couldn’t believe he was being banished from class for a week.

And so he left, and he really tried during that time to understand “What is he talking about, what does gentleness have to do with martial arts? What does he mean don’t enforce my strategy or get it out of my head? I don’t understand what he’s talking about.” And he got really frustrated and finally he took a boat and he went out into Hong Kong harbor, and he was just sort of like bobbing around in the water trying to think about what his teacher was telling him. And he got super frustrated and he leaned over the side of the boat, and he started punching the water with all his might. And in that moment he had an epiphany, and he just stopped and he said, “Oh my gosh, I’m punching this water with all of my force, and it is moving out of the way. It’s making room for my fist.”

And then he tried to grab the water, and every time he would grab it, it would just run through his fingers. And he was like, “Okay, this substance which seems so soft and weak and nothing, is actually can be the strongest thing in the planet. Storms, and it can carve through rock, and it can do all of this stuff, and yet I can’t grab it, it moves around me. And when I punch at it, it doesn’t suffer injury. It gets out of the way.” And he just had this huge epiphany, and then right after that he saw a bird fly over the water, casting it’s reflection, and he thought, “Oh, this is how my mind is supposed to be. It’s supposed to be like the reflection of the bird on the water. The water sees it but it just lets it pass through. And that’s how my emotions and my thoughts should be when I’m trying to fight and engage in combat.”

And it was then that he just sort of got this big download. And of course, being 17, he didn’t like immediately go home and write down the “Be Water” quote, but it was from that moment forward that he really started to apply this notion of fluidity and gentleness and really following the opponent and being in relationship with your opponent, and all of these things. And it was later, it was more in the late 60s, early 70s, when he really created that quote that we all know now, and started saying it out loud to people all over. But he had many writings about the nature of water, which can be found a lot obviously in the Dao De Ching, and in Daoist principles as well, which are very based in the natural world. But that’s where it started, is when he was a teenager.

Brett McKay: And I think we all can kind of intuitively understand why you’d wanna be water in a fight, right? You flesh this out, how can you apply this idea of “Be water” outside of martial arts? What does that look like?

Shannon Lee: I mean, I talk about this in the book, I feel like a fight is actually… Or a challenge, let’s say, is something that we’re facing all the time in our lives. Even if it’s just like the challenge of getting up in the morning. Or greater challenges that are thrust upon us as have been for many people over this last year. I think that being like water applies across the board to the experience of living, because life is challenging. Even when life is good and we feel good, we are still trying to figure out how to live our most fulfilling life and how it can be better and how we can fulfill our purpose and all of those types of things.

So whether we’re facing a difficult challenge or whether we’re facing a challenge of just trying to be even better and better, we’re still challenging ourselves every day in how to live the most fulfilling life. Or how to live a pain-free life, whatever the circumstance. And so being like water is extremely helpful, because we will be faced with obstacles and learning how to be flexible, how to be fluid, how to flow with our obstacles rather than ignore them or run from them or deny them, is part of being like water, being in relationship with what’s going on around you, as water is. It’s also about being present to your circumstance, and about being always moving forward and being unrelenting in that way.

Water, when I talk in the book I talk about living water, water that is in motion, even if it’s a still pool of water, it’s being fed from a deep source in order to stay viable and fresh. So my father talked about living water, and he equated the notion of being like water to the notion of truly living, because life is in motion all the time, and we need to be in response to it, like water is in response to its surroundings. It’s in response to the shore, the sand, the weather, the rocks, wherever it is, we also need to be in a sense of fluid readiness, to be able to respond to our lives in the most present way that we can.

Brett McKay: Another concept related to “Be like water” is this idea that your father talked about of emptying the cup. What’d he mean by that and how did he empty his cup?

Shannon Lee: Yeah, so the “Be water” quote starts, “Empty your mind. Be formless, shapeless, like water.” And he used to say this all the time, “The usefulness of a cup is in its emptiness.” If a cup is full, you can’t use it, right? So it’s already in use, it’s preoccupied. And he likened the cup to the mind. And when he would say, “Empty your mind” he would say “Let go of all of your preconceived notions, all of your conclusions, your judgments, and empty that cup, make it clear and ready to receive what is happening now in the moment, without the burden of your judgment and your preconceived ideas.”

And when you do this you allow for the maximum amount of learning, the maximum amount of observation, the maximum amount of sensing, sensory input. And you want to leave yourself open for whatever may come, so leave yourself open for a new solution, a new understanding, an epiphany, to learn something you didn’t know before, to sense something you didn’t realize was happening before. And this applies to martial arts and it applies to life. The person who is the most open and aware, the notion of having an empty cup is the notion of being aware in the moment, of as much of what is happening as you can be, and not putting your judgment on it to say, “This is good and this is bad”, it’s just what is coming in, and I get to decide in every moment what it has for me, what information there is, what I think is happening, what I can learn.

And so it’s a very important step because… And I say this in the book, I say if this is the only thing that you work on for a really long time, which is to let go of your judgment in every instance that you can in your life, and to meet each instance of your life with openness and awareness, that’s huge. It’s huge. And it allows for perception, new perceptions.

Brett McKay: And one way your father emptied the cup is he had meditation practices that he did.

Shannon Lee: Yes.

Brett McKay: What did that look like? What did your father’s meditation practice look like?

Shannon Lee: Yeah, so my father… Thank you, I knew there was another part to the question. [chuckle] My father did meditate traditionally sometimes, we actually have a picture of him, sitting cross-legged, hands in his lap, eyes closed, meditating. But my father was such a kinetic human being, he was just moving all the time. And so a lot of times he would meditate in movement as well. So he liked to get up in the morning and go for a jog. Jog a couple of miles, sometimes two, three, four, five, six miles, and he loved that as quiet meditation time, time to let the mind be loose.

So, there are a lot of different ways to meditate, and I’m sure there are meditation teachers who would say, “No, this is what meditation is”, or “No, this is how you’re supposed to do it” and all of that, but for me, I do advocate for meditation because it gives you that space in your mind to loosen it, for it to become fluid, for it to empty out of all of the thoughts and feelings and things that are going on in there all the time. So my father would employ meditation all the time. Sometimes he would just walk around the backyard quietly, allowing his mind to contemplate deeply, whatever his sense was and to create that opening within.

Brett McKay: As we said earlier, your father’s philosophy wasn’t dogmatic, and there’s this pivotal moment early on in his career where it came to like… It’s like dogmatism versus Bruce Lee. And what was going on is your father’s starting some martial art studios in California, but the guys in Chinatown, the traditionalist, this was in San Francisco, they didn’t like it, ’cause they were like “You’re not doing it the way you’re supposed to do it”. And basically there was this showdown. Can you walk us through this showdown and how did that influence the rest of your father’s career and how we thought about his philosophy?

Shannon Lee: Yeah, this was a huge pivotal moment for him, and so he had opened one school in Seattle and then he had decided to move to Oakland to open a second school, with his friend James Lee. And he went down there and opened a school which was open to anyone and everyone, which back in the day was not done. You didn’t teach Chinese Kung Fu to non-Chinese. Certainly there were some schools that would let a person in here or there, but it was definitely the exception and not the rule. And my father was interested in sharing his love of Chinese Kung Fu with whomever had a sincere desire to learn it. So he opened this school and had a whole bunch of people, and then he started changing some of the traditional Wing Chun that he had come up learning in Hong Kong, to be in his… Experimenting with what was more effective and slightly changing some of the traditional moves.

And he would go around and do demonstrations and call people up on stage and tell them why their moves weren’t effective, and why it was better to do it this way. And this really angered, as you mention, the traditionalists, who were like, “Who is this young upstart telling us that hundreds of years of traditional Chinese Kung Fu is incorrect and teaching women and people of all different backgrounds and races?” and what have you, and making this big star and they really, really didn’t like it. And so they issued a challenge to him, and they found their best fighter and they issued a challenge and they said, “We’re gonna challenge you to a fight. And if you lose you have to stop teaching, and if you win then you can go on teaching.” And so my father was incensed, and was like, “Great, fine, let’s do it.”

And so they came to his school in Oakland, it’s at the very end of 1964, my mom was eight months pregnant with my brother, and she was there along with James Lee, who is no longer alive. And they came in and they said, “We’re gonna have this fight”, and they started laying out all these rules, “There’s no this, there’s no that.” And my father said, “No, no, no, no. If we’re fighting for something as meaningful as this, there’s not gonna be rules, we’re gonna fight all out.” And so they conferred and they were like, “Okay, alright. Great, no rules. Just until someone gives up or someone’s knocked out.” And so they started and my dad just came out swinging. And the fight lasted about three minutes, my father won, the other guy gave up. And that was that. And they left.

And then I always remember my mom telling me this story and she said, “I came outside to see your dad and he was sitting on the curb with his head in his hands, and he seemed really upset.” And I said, “What’s the matter? You just won. Aren’t you happy?” And he said, “The fight didn’t go the way I thought it was gonna go.” And because there were no rules, and because the fight devolved immediately, as soon as the other guy found out that he was potentially outpaced, he turned and started running around the room, and my dad had to chase him and do all these things that you wouldn’t do in a traditional pairing off, and he was winded and it took him a lot longer to grab hold of him and get him down, and he was really disappointed with his performance, even though he had won.

And I talk about his ability to really assess himself and to really look at his pain points and his disappointments, and say, “So what can I do to change this?” And it’s from this moment where essentially Jeet Kune Do was born, his martial art that he developed. And he took an entirely different approach to martial arts and martial arts training, out of this. And he went so far actually as to ask his friend George Lee, who was a metal worker, to fabricate for him a miniature headstone, and on the headstone he wrote the phrase “In memory of a once fluid man crammed and distorted by the classical mess.” And I still have that headstone, and it was his sort of reminder, this symbol that he created, to remind himself to die to all his crammed distorted mess that he had gotten himself into, and just figure out a way to return to fluidity.

Brett McKay: That was the other thing that impressed about your father, and again, it’s this idea of taking the abstract and making it concrete. And you talk about this, this idea of… He made this grave stone as a concrete manifestation of this idea, of this experience he had, but he did this with other stuff, like he made other symbol throughout his life, sort of moral reminders or philosophical reminders that were concrete. Any other ones that stand out to you?

Shannon Lee: Sure, actually out of that same encounter he had these plaques created, which he called “the stages of cultivation”. And there were these four plaques that talked about the different levels that you would need to move through and attain in order to become whole, as a martial artist or as a human being. And they start with partiality, move to fluidity, and then emptiness, and then the final plaque was the plaque that he created to represent himself, as his philosophy and his whole representation. And he had his friend George Lee make those as well, and he designed them up and drew them, and he had them hanging in his school.

And he also had created this symbol, which was a yin-yang symbol with arrows around it, showing the ever fluid interplay of energies. And then around that he created the phrase, which I mentioned earlier, “Using no way as way, having no limitation as limitation.” And he had that written in Chinese characters around the yin-yang symbol. And he had that made into a medallion that he wore around his neck. And at another point he wrote an inspirational phrase on a business card and had a stand made for it when he needed some extra inspiration during that time in his life. So he was constantly creating these little symbols to remind him to stay on the path. He carried also like affirmations in his pocket that he would say to himself out loud, so he was a very… He had tools. [chuckle] He had serious tools.

Brett McKay: Right. And another tool that he used, and the reason we know the stuff that we’ve been talking about, ’cause he journaled. He was an obsessive journaller, he wrote tons and tons. What was his journaling practice like? Did he have a particular way he journaled, or was it more just like whatever thoughts he had he just sort of stream of conscious put it down?

Shannon Lee: Yeah, so he didn’t have a journal as we think of it today, it’s not all in one or several bound books. He was a little too kinetic, I think, for that. He would write stuff down wherever he was. He did sometimes carry little notebooks with him, but just to be able to capture anything he was thinking of at the time, since they didn’t have smartphones back then.

But he would write on all manner of pieces of paper and just keep them. He was really into… He had stationary created for himself as well, which was something that was easy to do in Hong Kong, and he wrote in a number of different ways. So, he wrote inspirationally, like “I have a thought, I’m gonna jot it down.” He wrote very methodically as well, in a sense that if he had an idea that he was working, he would work on it on the page. And there would be multiple drafts often times, of letters or essays or ideas that he was masticating and trying to work his way through. And I’m really grateful that we have all of all of these things, so that we can not only see the finished product but see his process as well.

And one of the things that I remark about his writings, which as I was going through them became really prevalent to me is that their are no negative writings. I mean there’s no place where he’s complaining or raging on the page, if you will, about his problems or his frustrations. If he did that he didn’t keep that stuff. And I point this out because, I know as a young girl who got into journal writing at a pretty young age, that was a lot of the first many years of my journaling, was just like, “So and so is really annoying me and I’m so upset about this and dadada… ”

He journaled very constructively, he was problem-solving and trying to express himself, and I just found that to be so amazing when I realized that. And I thought, “Wow, first of all, I’m so grateful to have this, but also this is actually something meaningful to me.” Because when I look back on those old journals of mine, of me sort of complaining and groaning about this, that and the other, there’s not a lot of useful information there for me anymore, because now I’m a different person than I was then. And what I see is me prolonging my suffering by concretizing it on the page. So I think that this is a really interesting practice, which is if you need to rage on the page, do it, but then throw it away and then start really using your analytical mind and your soul and your emotional body to seek your solution.

Brett McKay: Be constructive with your journal writing.

Shannon Lee: Yeah.

Brett McKay: Yeah, one of the stories you talk about that really hit home with me was your father, early on his career, he suffered… He was just about to take off basically, here in the United States, and he suffered a back injury. He was lifting weights, doing a good morning, which is… It can be a dangerous exercise, the mechanics of it, but he injured his back and it put him out of commission for a year. And I think most people would have fallen into a funk, been depressed, like you said, your father did feel those but then he always responded positively with a constructive action. So how did your father respond to this setback and what have you taken away from that?

Shannon Lee: I think that this is a similar moment to the one we were discussing earlier, which it was a different kind of pain, and he was in a lot of physical pain, he had injured his fourth sacral nerve and damaged it really badly to the point where he was told he would never do martial arts again, and that he may never walk easily again. And as you say, the thing about my father, he definitely felt his feelings, he didn’t just ignore that. And he was upset and depressed for a minute, but then I think the thing that’s important is once you know that that’s how you feel and you’ve expressed those feelings, and I think back to me being in so much pain over my brother’s death, and I just hadn’t worked up any tools for myself.

Where my father differed was, he had tools. And so for him in that moment it was like, “Okay, this is what has happened. Now what?” And so he didn’t know if he was gonna be able to work himself back into any kind of health, but he was gonna see if he could. And so in this library of books of his that I have, are many books about anatomy, about back pain, how to exercise your back, books about kinesiology, all sorts of things on how to sort through for himself what was going on with the problem, and how he could deal with it and try to construct some sort of recovery for himself.

In addition to that, because he was bedridden for a number of months, he was gonna make use of his time. So it’s actually during this time that we have so many of his writings on martial arts. He started working on these… We have seven volumes of his writings on martial arts called “My Commentary on The Martial Way”. And he also read a number of self-help books about positive attitude, about positive thinking and practices. And one of the things, which I mentioned earlier that he did, was he wrote the words “walk on” on the back of one of his business cards, and he had a little stand made for it, and he put it where he could see it from his bed. And it was his reminder to just keep moving forward, just keep spending each day using his time, seeking his cure, figuring out what he was gonna be able to do.

And then writing, writing, writing. And he wrote so many philosophical essays and thoughts, creative ideas, as well as technical writings on martial arts, during that time. And if it hadn’t been for that time, we would not have that. And so I think the important thing here is that he was like, “You know, here’s the thing: I’m alive, and as long as I’m alive then I might as well be working towards something.” And I think that was really his attitude, which was, “Okay, if I’m gonna be stuck in this bed and then I’m gonna do what I can from this bed. And I’m gonna attempt to see if I can also figure out how to make my body stronger as well”, which as we know, he ultimately did.

Brett McKay: The other thing, I had to keep reminding myself as I was reading the book, ’cause all these insights are just like, “Wow, he’s probably in his 40s, 50s when he wrote… ” You always forget, your father died when he was 32 years old.

Shannon Lee: Totally. I think about myself at 32 and I’m like, “Man, you were a mess. [laughter] What did you know at 32?” I mean, I knew some things, but he was just this force of nature in terms of, as we mentioned, like putting things into action. And as a kid his nickname was “Mo Si Ting”, which means “never sit still”, and that was really his thing, was that he just was this kinetic ball of energy. And so he was gonna do, do do, do do. And so when I say like, “Oh yeah, my dad was as an action hero”, I mean it in the broadest sense of the meaning, not just films. He was a man of action. And yeah, I feel like I finally came around to being able to express what I expressed in this book in my 50s [chuckle], but I also say to people, “That’s the gift of a long life.” I got the opportunity to live my life long enough to get there.

Brett McKay: Right. Well, Shannon this has been a great conversation. Is there some place people can go to learn more about the book and your work?

Shannon Lee: Thank you. Yes, well, you can go to Brucelee.com to check out all things Bruce Lee. We do share a lot of his philosophy through our social media as well, which is @BruceLee. There’s also The Bruce Lee Podcast, which is an applied philosophy podcast, so if you wanna learn more about his philosophy and listen to us discuss it and break it down, because there’s much, much, much more to his philosophy than the “Be water” aspect of it as well. You can listen to the Bruce Lee Podcast, and I also have my own social, @therealshannonlee.

And I just wanna say quickly that the reason that I got into looking after my father’s legacy is because of the philosophy, because of that dark moment in my 20s where the philosophy changed the course of my life and helped me to heal. And I felt like my father’s legacy doesn’t really need any help from me in the sense that he himself is a discovery that people will continue to love and admire all on its own. But I wanted people to know this side of him, and I think from reading the book you can really get the sense that he wasn’t just an armchair philosopher, he was a really educated, deeply contemplative man, who was really a philosopher at his heart.

Brett McKay: Well, Shannon, thanks so much for your time, it’s been a pleasure.

Shannon Lee: Thank you so much.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Shannon Lee, she is the daughter of the late Bruce Lee, the author of the book “Be Water, My Friend: The Teachings of Bruce Lee”, it’s available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find out more information about the work they’re doing with Bruce Lee at Brucelee.com. Also check out our show notes at aom.is/leephilosophy, where you find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of The AOM podcast, check out our website at Artofmanliness.com, where you find our podcast archives, as well as thousands of articles written over the years. And if you’d like to enjoy ad-free episodes of the AOM podcast you can do so on Stitcher premium. Head over to stitcherpremium.com, sign up, use code “manliness” at checkout for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the Stitcher app on Android or iOS and you can start enjoying ad-free episodes of the AOM podcast. And if you haven’t done so already I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on Apple podcasts or Stitcher, it helps out a lot.

If you’ve done that already, thank you, please consider sharing the show with a friend or a family member who you think will get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding you not only to listen to the AOM podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.