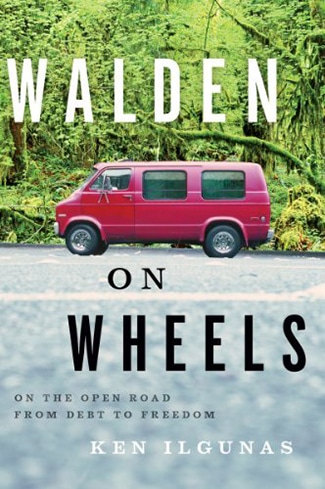

Millions of young adults know what it’s like to graduate from college with student debt. For some, it’s a frustrating annoyance. For others, it’s a worry-inducing burden. For Ken Ilgunas, it was a dragon in need of slaying and a pathway to adventure.

Ken is the author of Walden on Wheels: On the Open Road from Debt to Freedom, and today on the show, he shares the story of how his quest to erase his debt led him to the Arctic Circle and through the peaks and valleys of living a totally unshackled life. Ken explains why he went to Alaska to work as a truckstop burger flipper and park ranger to pay off his student debt, what it’s like to hitchhike across the country, how reading Thoreau’s Walden got him questioning how we live our lives, and how that inspiration led him to living in his van while attending grad school at Duke. Along the way, Ken shares his meditations on nonconformity, engaging in romantic pursuits, and the benefits of both de-institutionalizing and re-institutionalizing your life.

Resources Related to the Podcast

- Walden by Henry David Thoreau

- AoM Podcast #841: What People Get Wrong About Walden

- AoM Podcast #473: The Solitude of a Fire Watcher

- AoM Article: How to Hitchhike Around the USA

- Sunday Firesides: The Cost of a Thing

Connect With Ken Ilgunas

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. Millions of young adults know what it’s like to graduate from college with student debt. For some, it’s a frustrating annoyance. For others, it’s a worry inducing burden. For Ken Ilgunas, it was a dragon in need of slaying and a pathway to adventure. Ken is the author of Walden on Wheels: On the Open Road from Debt to Freedom, and today on the show, he shares the story of how his quest to erase his debt led him to the Arctic Circle and through the peaks and valleys of living a totally unshackled life.

Ken explains why he went to Alaska to work as a truck stop burger flipper and park ranger to pay off his student debt, what it’s like to hitchhike across the country, how reading Thoreau’s Walden got him, questioning how we live our lives, and how that inspiration led him to living in his van while attending grad school at Duke. Along the way, Ken shares his meditations on nonconformity, engaging in romantic pursuits, and the benefits of both deinstitutionalizing and re-institutionalizing your life. After the show is over, check out our show notes at aom.is/waldenonwheels.

All right, Ken Ilgunas, welcome to the show.

Ken Ilgunas: It’s awesome to be on. Thank you.

Brett McKay: So you had a varied and unique resume after you graduated college. So you moved to Alaska. And then while you were there, you cleaned a motel at a truck stop there near the Arctic Circle. You flipped burgers during the night shift at a diner at this truck stop. You guided cruise tourists. You worked as a backcountry ranger in a national park. Then you hitchhiked from Alaska to New York. So you’re kind of a tramp for a bit. You served in the AmeriCorps in the American south. And the capstone, there’s some other stuff you did, too. We’re going to talk about it. But the capstone of this career that you had after college was you lived in a van on the campus of Duke University from 2009 to 2011 while you pursued your graduate degree.

And what’s crazy, you did all this stuff so you could pay off your student debt. Let’s talk about this. Like, how much debt did you acquire during college? And was there a moment you had in your life when you saw your mounting debt? And you’re like, Oh, my gosh. I got to do something about this.

Ken Ilgunas: It was $32,000, I think, with interest, that climbed up to 35,000 that I had to pay off. For the most part, I did a good job, as so many growing debtors do, in that I just completely put it out of my mind. When I was at college I never really thought about debt. I was just focused on my part time job, writing my essays, getting whatever grades I needed to get. So I just kind of put it out of my mind. And then one day, I think this was maybe after my third year, my mother called me down to the kitchen table. I was commuting to the university at Buffalo in New York, and she had all of these kind of loan bills and papers just kind of piled up on the kitchen table. And she’s just like, you’re going to be in a lot of debt. And at this time, I was pushing carts at the Home Depot for $8 an hour, and she was just like, what are you going to do? Like, how are you going to get out of this situation? And I just kind of said, Mom, don’t worry about it. I’ll deal with it. And I always had fantasies of just like moving to a different continent or faking my death or just weirdly happening upon a well paying job, just stupidly optimistic. And I just kind of joked around about it.

And it was one of the few times in my life where I saw my mom fold her arms and put her head down and weep. She was so scared for me. And that was kind of a wake up moment. I was just like, Wow, I really do need to think about all this debt I need to pay off.

Brett McKay: And a lot of that debt you talk about in your book, Walden on Wheels, a lot of that debt you acquired, it happened during that first year of college because a lot of high school students, you think, well when I’m gonna go to college, I’m gonna go to the best college I can get into, and I’ll worry about how much it costs later. So I guess the first college you went to was kind of an expensive private school, right?

Ken Ilgunas: It was an expensive private school called Alfred University in Southern New York, now, it’s not that expensive to a lot of students who can get grants and scholarships. I was just a lousy, slouchy high school student, so they just charged me as much as they could. So, yeah, I racked up about $18,000 in debt just from that first year alone. And it didn’t take me long to realize I’m probably not going to be someone who makes the big bucks someday. So then I changed schools to University at Buffalo, which is a state of New York school. So that was kind of mistake number one. But when you’re in high school, this is like the first big decision you have to make. What school are you going to go to? And you just don’t want to have a mediocrity frame of mind. This is your first thing. You want to kind of launch yourself into the world and be ambitious and go for the best thing you can. And I was told again and again, don’t worry about the debt. Just go to the best school you can. So that kind of what got me into this problem.

Now, if I was advising other young folks, I try to say go to the best state school you could go to and save yourself a lot of grief if you can.

Brett McKay: So third year, your mom sees the bills and she starts freaking out. And that kind of had you have a come to Jesus moment about your debt, and you got really motivated to pay off your student loans. What was behind that besides your mom crying? Was there something else going on where you’re like, Man, I want to get rid of this stuff as fast as possible?

Ken Ilgunas: There was a couple things. One, I was right on the edge of being a loser, low status man who can’t get a date. So there was just kind of desperation and really wanting to self improve. And getting rid of my debt was kind of the obvious thing. And, oh, man, what I wanted to do was be a journalist. I joined the student newspaper at university, and I loved it. I interned at Alt Weeklies, and I kind of put all my eggs in the journalism basket. So I applied to 25 paid newspaper internships. And over the course of my last semester, I got 25 letters in the mail rejecting my applications. So I was kind of just standing there in my underwear, completely vulnerable, having no idea what to do. Because if you don’t deal with your debt, the interest accrues and swells, and suddenly a $30,000 debt could be a $50,000 debt. So part of it was just desperation. But I don’t know. I guess I had romantic longings.

And by romantic, I’m not talking sexual romantic, I’m talking more of, like a sentimentality. I wanted a life of adventure. I wanted to pursue dreams and goals. I wanted to live my life fully and interestingly and in the way I wanted to. So I saw my debt as this ball and chain, which was going to prevent me from living that life.

Brett McKay: So instead of getting just a regular job so you can pay off that debt as quickly as possible. You decided to go to Alaska and work these odd jobs. Why did you go that route? Was it just because you couldn’t find a regular job? So you’re like, Well, I’ll go to the Arctic Circle and see what happens there?

Ken Ilgunas: Yeah, it was a bit of a little things. One, it was like, if I had a job offer in journalism, I would have taken that. But I didn’t have that. The previous summer, for a couple months, I worked up in Alaska so I had a connection there. So it was just like, if this is my worst case scenario, cleaning beds or flipping burgers or tour guiding visitors up in the Arctic, I’ll take that over getting my old job at the Home Depot, pushing carts and sleeping in my boyhood bedroom. So, yeah.

And when I went up to Alaska, I was a bit depressed because it’s just like, here I am working these, a low wage, low skill job, which I would have been perfectly able to do out of high school, except now I have a college degree, $32,000 in debt. This is not an idealistic career. I don’t feel like I’m launching myself towards anything meaningful. So I was just kind of like, I’m just stuck in this purgatory and I could be here for, who knows, like, 10 years working jobs for low pay. But what I quickly realized was I accidentally landed myself in an almost ideal situation to pay off my student debt. And that’s because a lot of these jobs up in Alaska and out west, they provide room and board, meaning your rent and your food.

So when I was living up there, I had no cost. I had no health insurance. I didn’t have to pay for my food. There was no cell phone service. I didn’t need a car. I had literally no bills at all, except for my student debt. So I just decided I’m just going to put everything I can towards my student debt, making $9 an hour and working a full year. You don’t make much working $9 an hour. I think I accumulated $18,000, which to a lot of your listeners will sound pathetic. It’s like, oh, you worked year round, you made 18,000. But guess what? I saved $18,000.

Now, working kind of a normal job in a normal American town, how much do you need to make to save $18,000? I calculate about $50 to $60,000 living a normal American lifestyle, then you can save 18,000. I did that working up in the Arctic. And that would be really helpful when it came to paying off my debt.

Brett McKay: You, in this book, Walden on Wheels, you do a compare, contrast between you and your friends. You have a really good friend from high school who was having the same problems, had a lot of debt, couldn’t find a job after graduating college. And while he was doing the job search, you were up in Alaska, in the Arctic making $9 an hour. But you were paying down your debt and this guy’s debt was just constantly accruing.

Ken Ilgunas: Yeah, he graduated with something like he thought it was 58,000. And then one day he got a letter in the mail and they’re like, oh, it’s actually 8000 more. So, yeah, it was something like, I don’t know, $65,000 in debt. What he wanted was control. He wanted kind of a stable situation, a decent job where he could begin chipping away at that debt. What I wanted was urgency. I wanted to pay off my debt as fast as humanly possible. And I was a little crazy about it. I call it practical insanity. And what I mean by that is when you take things like, I don’t know, narcissism, delusions of grandeur, megalomania, OCD, just obsessive thinking. And then applying that to a problem to help you get over kind of insurmountable odds. So that’s kind of how I thought about. Of my approach to this. It is just like, be crazy, be obsessive and kind of devote your whole self to this.

Obviously, there’s some drawbacks to that. Mental health drawbacks to that. ‘Cause you don’t feel like you can take a break at all. ‘Cause if you’re just so obsessed with your goal. And I think I also kind of had… And this was all unconscious at the time. I didn’t articulate it this way when I was 22. This is just me, 40, thinking about it. But I was also, as I said earlier, I just kind of had a romantic frame of mind, kind of like a mythopoetic. And I thought of my debt as like a dragon to slay and me, this hero, up against it.

So if you can apply these kind of romantic frame of mind to something like that, it can help you get over something big.

Brett McKay: Well, speaking of this romantic frame of mind, did you go to Alaska also… Was this also there’s some kind of Jack London romanticism going on. You’re thinking, I’m this kid from the suburbs who hasn’t tested himself. And I’m going to go to the wilds, the great north, to see if I can withstand it. Was that going on too?

Ken Ilgunas: I was always drawn to Alaska. I begin my book, Walden on Wheels, with I dreamt of grizzly bears because I had these chronic dreams of grizzly bears. These grizzly bears would be just munching grass in my western New York suburb. And I remember in my dreams, I’d just be in awe of these big brown towers of fat and fur. And I was just like, Why am I dreaming about grizzly bears? And I remember one day it. I looked at an atlas, and I saw Alaska, and it was just like I was drawn straight to that place. And I don’t know why exactly. Looking back, I think it was because I’d been such a suburbanite growing up. I grew up just outside of Buffalo, New York, Niagara Falls, New York, around these boneyard deindustrialized cities where there’s kind of endless cookie cutter suburbs, just landfills. 4 miles from my home was Love Canal, the site of this 1970s environmental disaster.

And I just saw people around me. It was almost like the people living around me. They weren’t living a life that kind of accommodated normal human instincts. They were going to these 9:00 to 5:00 jobs, they hated, paying bills for the rest of their life, cramming vacations in tiny two week windows. And it just seemed crazy to me.

And I think I wanted an escape. And again, this was all kind of unconscious. And I think there was something in my subconscious saying, You need to get out of here. You need to go to somewhere completely wild, and then maybe you’ll kind of escape this surreality of the suburbs. And I’m happy I listened to that inner voice.

Brett McKay: So you were in Alaska. You did a bunch of different stuff at this truck stop. What was life like working at this truck stop in Alaska? What kind of people were you interacting with? Kind of give us a day in the life of… I mean, you’re pretty close. I mean, you’re in the Arctic Circle, right?

Ken Ilgunas: Yeah. I was 60 miles north of the Arctic Circle. This was about 250 miles north of Fairbanks. So the nearest store, stoplight, movie theater, whatever, was 250 miles away. And I’m right in the middle of the Brooks mountain range, which, if any of the listeners haven’t seen it, try to go up to the Brooks Range someday, because it’s one of the most amazing, wildest landscapes left on earth. It’s this 800 miles east to west mountain chain full of grizzly bears and moose and herds of caribou and wolves and… Yeah, so the population of there was 32, not 32,000, 32 people. And half of it, I’d say, were kind of debt ridden college students. And the other half were just kind of working class folks who did this for a living. Kind of bounced around from camp to camp. So there was a good mix of people.

And I just found myself working alongside and living alongside truckers, pipeline workers, carpenters, a lot of weirdos. I mean, if you’re going to go 60 miles north of the Arctic Circle, you’re going to be a bit different. So I remember I lived in a dormitory, and on one side of me was this young man from Utah who was just high all day long.

And this was a big step up for him. He worked at a porn shop where he had to clean up booths every day. And then the other side of me was this half White, half Vietnamese guy who was a schizophrenic. And I’d constantly hear him talking to himself. And every day he would bust open his doors and he’d have two invisible machine guns on his arms, and he’d start to shoot people with this invisible machine gun. And it was very kind of interesting, from a sociological and anthropological perspective to rub elbows with people who were normally outside of my bubble. And it was that way for a few years up there.

Brett McKay: And there was one guy in this town. We can call it a town. It’s Coldfoot, right? It’s the name of this place.

Ken Ilgunas: Yeah.

Brett McKay: There’s this guy who would later serve as the inspiration for your van dwelling phase of your life, which we’re going to talk about. Tell us about this guy.

Ken Ilgunas: Well, there was actually two older gentlemen who really inspired me. The first was this guy named Jack. And he lived in a town 12 miles north, this semi subsistence village called Wiseman, which had, like, 15 people living in it. And he hunted for a living. He fished, he trapped. He grew his own vegetables. This was the most northern vegetable patch in North America, to my knowledge. He had solar panels. He had his own wind turbine. He had this beautiful cabin. And I was just transfixed with his life. This is someone…

There was kind of no division between life and work for him. He went out and hunted and fished. That was his work. And he came home and cooked, like there was just kind of no separation as there was back in kind of contemporary American society. So I was really inspired by that. And then there was this older gentleman, James, he was in his mid 70s. He had this long white kind of mountain goat beard, and he worked for the Bureau of Land Management. And he lived in his 1980 Chevy Suburban truck, this yellow truck. And he did that for six years in the Arctic. Now in Coldfoot, it once got to negative 81 Fahrenheit. I don’t think it that got that cold when he was in living in his truck. But he lived in that thing for six winters. He put a little propane stove that popped out of the roof of his truck. So I kind of looked at these folks up in Alaska, and they were just living lives the way they wanted to. They were living them creatively with imagination, with independence. And I thought I could take this kind of wild style of thinking back with me down into the lower 48.

Brett McKay: What did you do when you were working up there, when you weren’t working, right? So you didn’t have the internet, you didn’t have cell phones. How did you keep yourself entertained and not going crazy, particularly during the long, cold, dark winters?

Ken Ilgunas: Yeah. The winters were tough. That’s when the town went a little bit crazy. [laughter] That’s when people started drinking. They were doing drugs. There was a lot of cliques. I’m talking like 12 people. [laughter] There’s like just tidy cliques.

Brett McKay: Wasn’t there like people crapping on people’s cars or something like that too?

Ken Ilgunas: It got pretty hostile. Yeah. There was some roof defecation happening. One guy poured some water on someone’s husky, which you don’t want to do when it’s negative 20 below. They would go on these drunken joy rides and once they went off a cliff and into a frozen river, and I’m like, Okay, thank God they’re gonna get fired. And they were back at work the next day because you can’t just fire one fourth of your workforce. So I would just kind of hide away and went inward and I was reading a lot. That was the most books I ever read in a year. I think I read 62 books that year despite working long hours and just kind of planning my exit. I didn’t know what was next for me. But yeah, I was studying for the GRE, I was thinking about grad school. I was starting to really crave going back to school.

Brett McKay: So one of the books you read and all that reading you did was Henry David Thoreau’s Walden. What did that book do to you when you’re in Alaska?

Ken Ilgunas: You know one of those books that you read and you’re just like, underlining almost every word in it?

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Ken Ilgunas: Or you just find yourself nodding your head and recognition. And he wrote that I think in the 1840s, but it felt like it could have been written apart from the archaic prose. It felt like it could have been written in the 21st century. And I remember reading this passage where he’s talking about shelter, and he would go past the railroad and the railway workers would lock up their tools and this little six foot by three foot shack, which at the time sounded like a coffin to me. And he’s like, for a dollar, anybody could live in one of these. And then he says, if you think I’m jesting I’m not. And I just love that. I love… It reminded me of the folks in Alaska, like they’ll do whatever it takes to make it work.

They’ll use that imagination, they’ll think out of the box. And I admired Thoreau for just being kind of like an artist of life. He thought very deliberately, he wanted to craft his life in a very specific way. The same way an artist, very meticulously put something onto her canvas. And I too wanted to be an artist of my life. I wanted to design my life. I didn’t want my life just to happen to me like it had been happening. I wanted to carefully think it through. So between Jack and James and Alaska and Henry David Thoreau, I was questioning everything. I was questioning how we shelter ourselves, how we work, how we live, and how we transport ourselves, which probably we should probably get into hitchhiking, right?

Brett McKay: Yeah. We’re gonna get to hitchhiking.

Ken Ilgunas: Okay. [laughter]

Brett McKay: But before we do, tell us again how much debt you’re able to pay off thanks to your work in Alaska.

Ken Ilgunas: So that first year I made 18,000. And again, there was some mental health drawbacks to being so obsessed. So the one kind of fix I applied was any tip money I made as a cook or a guide. I was like, Okay, that’s yours. You can do whatever you want to do with it, but everything else goes towards your debt.” So I think I made 22 grand and 18,000 went to my loans and it would take me another year and a half to fully pay them off.

Brett McKay: During your stay in Alaska, this is kind of a detour, you went to go see this Canadian motivational speaker who did 18th century Canadian explorer reenactments. So he would get in a canoe and go down these rivers and then you ended up doing an expedition with this guy. How did that happen and did you get paid for it? Was this part of the plan of paying off your debt or was this something you just thought, Hey, this would be fun to do?

Ken Ilgunas: It had nothing to do with the debt. What had happened was after the tourism season in Alaska died down, my boss invited the tour guides to this tourism convention in Valdez, Alaska. And one of the motivational speakers was this guy named Bob, I forget his last name, but he puts together annual voyages across Canada, kind of replicating some of the historic voyages of the voyageurs who were kind of the fur traders in the 19th and 18th century Canada. So I was listening to him talk about his voyage across Ontario and Quebec, and he said, at the end of this, I’m actually trying to put together a team for the next summer. Let me know if you’re interested.

So at the end of that talk, without thinking about my debt or anything like that, I just walked up to him and put my hand out and I said, Bob, I’m your man. [laughter] And sure enough, I got selected for that summer journey. So for two months across Ontario, Canada, I think it was about a thousand miles. We lived as if we were in the 18th century. So we didn’t have tents, we didn’t have sleeping bags, we didn’t have toilet paper or bug spray. We had two very leaky birchbark canoes. And it was as close as a person can get to living in a different century, I think.

Brett McKay: What did you get from this experience? Just memories? Or did you actually develop any skills that you could say, I could take this and apply it to my life?

Ken Ilgunas: I learned a lot about knot tying [laughter] which helped a lot. I think I learned a couple things. One, I never… So I’ve kind of talked about all these wilderness experiences I had, but I hadn’t been on a hike on a trail until I was 21 years old. That’s just not what you do where I come from in western New York, a lot of us don’t hunt or go camping or hiking. So this was all kind of new to me. And my relationship with nature was changing. I grew up in a hockey rink and on a football field and I thought of the mountains as just another one of those arenas, like something to win, you beat a mountain or something like that. And when I was out in Ontario paddling over Georgian Bay, I began to feel something different.

It was almost like an indifference to nature because I think when you see nature through a windshield, it’s just like, Oh, that sunset is so beautiful and magical and serene. But a sunset when you’re out on the water, like that could mean, Oh man, here comes the mosquitoes, here comes the cold, here come the storms and you don’t have a tent or a sleeping bag. So I felt like I was just kind of becoming nature. That kind of divide that separates man from nature was just kind of dissolving. And as I noticed, nature was indifferent to me. I was kind of indifferent to it. So some of that mesmerization kind of went away a little bit. And I’d also say this, it made me reflect on how Americans were really lacking kind of just that period of no responsibility adventure.

We had this Métis guy on the trip. He was half First Nations, half white, and he would talk about how his tribes would go on these spirit quests where a young man would go off into the woods and starve himself and wait for a vision or something like that. I was like, Does kind of my sort of culture in America, do we have anything like the Native American spirit quest? And I was like, no, we really don’t. And I do think we used to have a legacy of traveling and journeying as young people, whether it was being a tramp in the 1930s or poets going on long road trips in the ’50s, or being a hitchhiker in the 1960s and ’70s. And it’s just like, we kind of don’t have that, we don’t have that thing that serves as a bridge between, school and career, that period of adventure. It’s just kind of been abridged from a young person’s life. And I just began to think, this is what we need. We need 21st century spirit quests.

Brett McKay: We’re gonna take a quick break for a word from our sponsors.

And now back to the show. Before you did this Canadian reenactment expedition, you had to get back home to New York ’cause Ontario was close to New York. And in order to save money, you decided to hitchhike, and hitchhiking, it used to be a thing in America, but it’s not anymore. First off, what do you know about hitchhiking culture? Do we know why hitchhiking went away?

Ken Ilgunas: We can take a few guesses. One, I’d say the crime rate in the 1980s up to the mid ’90s was pretty bad. And maybe that’s when hitchhiking culture really started to die down. Hitchhiking being represented in movies and whatnot. The hitchhiker was always the homicidal maniac that didn’t help at all. And I think Americans, we were just kind of undergoing this period of reduced social capital and public trust and just general fearfulness and paranoia. So I think that’s why we kind of stopped. But there are pockets in America where it’s still commonly done and not too hard. I think if you’re in the through-hiking community around a big through-hiking trail, the locals there see someone with a backpack and they know it’s just kind of normal and they’ll pick you up and whatever. Alaska, Yukon territories, British Columbia, Washington state, some of these western places, it’s still somewhat easy and practiced a little bit. But yeah, like where I grew up in Western New York, I never once saw a hitchhiker, so it’s just kind of more common in some places than others.

Brett McKay: What did you learn about people being a tramp for thousands of miles?

Ken Ilgunas: It was terrific. I mean, I would have to wait on the side of the road I’d say on average 30 minutes to two hours. I kept some calculations for a while. So you’d have to be on the side of the road for a while, but when you get picked up, you get the feeling of like a Christmas morning, it’s just like, Oh, thank goodness I finally got picked up. And then you have a few seconds to determine, Is this guy gonna kill me [laughter] or not? So you have to have a quick conversation to determine how sketchy they are. And I’d say I turned down less than half a dozen rides and I’ve accumulated probably 10,000 miles of, hitchhiking across North America. So very, very rarely would I turn down a ride. But it was a great time to… It’s like the ideal travel experience because think about any other way we travel, whether it’s cycling or on bus or train or planes.

When we get on a plane and travel 5000 miles, we usually have some earbuds in and watching a movie. We’re not talking to people, we’re not experiencing the culture. But when you’re hitchhiking, you’re thrown right into that person’s culture, like you’re gonna get to know that person really well. And what I found is after two hours of talking with a complete stranger, I’d often hear secrets they probably never told their wife, it was almost like a therapy session. And that’s how I paid for my ride by being a really good active listener. And yeah, you really get to see all sorts of folks. I don’t wanna say I grew up in like a complete liberal suburban bubble, but I sort of did and suddenly I’m getting in the car with ex-cons and people who tell me about their alcohol addictions or their meth addictions and people who had problems that were very different and far more extreme than the problems I grew up around. So in some ways it was very enlightening, but more than anything it just made me feel like we do have this wrongheaded and somewhat unfounded view of our country. I think we are overly fearful, overly paranoid. And when you’re picked up again and again by complete strangers who don’t ask you for money or any favors, you begin to see your country and your culture in a new and much more warm-hearted way. In some ways hitchhiking really renewed my love for being American.

Brett McKay: Any advice for people out there who are listening and thinking, I want to hitchhike. Any tips, tips for the road?

Ken Ilgunas: Well, you probably don’t need to listen to me. ‘Cause one of the the funnest parts about it is, is just learning how to do it on your own. But let me get you started with a few tips. The biggest one is placing yourself in a situation where the driver is probably going less than 30 miles an hour and has a lot of space to pull over. That’s the biggest thing. Also, dress for business, [laughter] you gotta dress nice, wear a nice ball cap, put on a collared shirt, tuck in your shirt into your pants and just look presentable.

Never show any anger or frustration because sometimes people will go past you and then feel guilty and then you’ll see that same person five minutes ago. So don’t kick the gravel in the road or show any frustration ’cause you will be frustrated.

There was times when I’ve just been in pouring rain for 12 hours and you’re so angry. It’s just like, you guys are all heartless. And also take a box of crayons and write a nice sign. Don’t use your thumb. Write a nice colorful sign that’ll make you seem a little bit more family friendly.

Brett McKay: Gotcha. I think that’s awesome. So you did this expedition, after the expedition, you had this period where you’re back at home with your parents. And you talk about how being back in your childhood home in the suburbs, you started falling into this funk and depression and the mountains, the wild started calling you again and this time you decided to go back to Alaska, but this time you were going to be a park ranger in, I think it’s like the most remote national park in the United States. So tell us about that experience.

Ken Ilgunas: Yeah. I remember I went back home and sometimes when you’re away from home for a few years, you can kind of see your milieu, your natural environment more clearly than before. And yeah, I had some really tough conversations with my mom. I remember once she sat me down and she said, Are you trying to kill yourself doing all this? And she told me she’s gonna start to distance herself from me because she just thought I was acting in a very kind of reckless and erratic way. And she once said, when are you gonna grow up and start acting like a human being? And I understood ’cause she was fearful of losing me ’cause I was hitchhiking and all that, but I’d never felt more like a human being. I’d never felt more alive and more charged with life when I was climbing a mountain in the Brooks Range or getting into a car and hitchhiking across Mississippi or something like that.

So I felt this very stark disconnect with the place I grew up and the life I wanted to lead. So yeah, yeah, I got a job with the National Park Service, which paid a lot more than the wages I was getting working at the truck stop. So this would help put me over my student debt and it was just an amazing job. I had this job as a backcountry ranger in the gates of the Arctic National Park where they dropped me off on a little four seater plane in the middle of the wilderness with these big bush tires or landed me on a pond out there. And I’d go on an eight day backpack patrol either on canoe or on foot. And I got paid to go hiking. And honestly that was enough, like having three months living in the wilderness. I didn’t kind of need any more adventure wilderness. That was like an ideal amount of time living in a state of adventure and the wilderness. ‘Cause then I was kind of eager to go back to school and embrace the life of the mind. It was just I… For a couple years I had a really nice balance between the life of the mind and the life of adventure.

Brett McKay: What are you supposed to do when you’re out on these trips? Were you writing tickets? What was your job?

Ken Ilgunas: Oh, no. You have to imagine, gates of the Arctic, it’s over 8 million acres, and it’s I think the second least visited national park, so over the course of eight days, I’d be lucky if I saw one group of people. So, no, I wasn’t that sort of a ranger, but it was more kind of presence to prevent poaching activity, any sort of trash clean-ups. Sometimes we’d be told to go in and take out an old gold mining barrel or a caribou collar or educate folks out there about bear safety and fire safety stuff, stuff like that, it was a great job. And probably one part of me could have just kept doing that for the rest of my life, but there was something missing, I didn’t want to… ‘Cause it kind of felt like a vacation, I felt like I was getting paid to hike and I’m sure there’s some listeners like, Oh, you had it made. But I was seeking something more. I wanted more of an existential spiritual fulfillment from my work and ranger-ing wasn’t that.

Brett McKay: No, if you’re a young person, I think I would have done this if I could do this again, jobs with the National Park Service or the US Forest Service, seem like they’re really cool. You can be doing something like you did, where they just drop you off for a week, you get to backpack in beautiful country and get paid well for it. We had a podcast guest on a long time ago, it’s one of my favorite episodes we did with this guy named Phillip Connors, and he is a fire watcher for the US Forest Service in New Mexico, and he just goes to one of the few remaining these fire towers where they’re looking for smoke, and he just lives there during the fire season, and it seems like a great gig. You’re out in nature you get to hike, and it seems awesome if people wanna listen to that, that is episode number 473, if they wanna check that out. Okay, so you did this backcountry park ranger thing, it was paying a lot. And because of this job, you’re able to pay off your debt, you’re finally able to pay off 32-34,000 dollars worth of debt. How did that feel? How did it feel to finally accomplish this goal that you’ve had for years and were obsessively trying to accomplish?

Ken Ilgunas: I wish I could say there was a celebration with champagne and confetti, but it wasn’t, I don’t even think I barely acknowledged it, ’cause I did the math months before and I kinda knew exactly when the debt was going to die, so it was kind of rehearsed in my mind, well, ahead of time, and I don’t know, sometimes you’re in a relationship that’s kind of bad for a long time, and when it comes to the break-up, you kind of feel nothing and it’s kind of because you’ve rehearsed this so many times in the past, and I think that was kind of the case with my debt.

Honestly, I miss the debt a little bit because… And that’s gonna sound crazy, but I just loved having purpose and a goal and something… A dragon to slay. So you kinda have to be ready to replace that one sense of purpose with another, and luckily I had something lined up as we’ll get to. I was ready to go to grad school. So yeah, there was no really real sense of relief or celebration. I was just happy it was gone.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I think it is what happens with most goals that you think a lot about when you finally get it, you might feel good for two seconds, and then it’s like, Okay, I’ve gotta find the next thing to work on, and so for you the next thing to work on was you’re gonna get your graduate degree and you decided to go to Duke University, but you did not wanna go to grad school and take on any more student debt, so to avoid that, you decided to live in a van on the campus of Duke University. So talk about just the van, you bought, what kind of van did you live in? Was it a creeper van? What are we talking about here?

Ken Ilgunas: Well, almost all vans are creeper vans. It was a 1994 Ford Econoline, and I should say this is back in 2009, so this was kind of before the whole #Vanlife movement, and I remember as I was thinking about the for real living in that coffin box, I was like, Oh, I could do that at Duke University, live in a little coffin or something. But a van made more sense, and I did some research online and I couldn’t find one person who’d done this before on a college campus, so I felt like a pioneer in a way, ’cause again, back in 2009, you were either homeless or a pervert, if you were living in your van, so I’m happy to help change the image away from that, so yeah, I thought If I could buy a cheap van and just live in it year round, then maybe I could avoid expensive apartment payments and I do all my cooking in the van and not move it around on campus, and the big thing was I had to keep it a secret, ’cause I did not want campus security or any students finding out because I thought if they found out they’re gonna spread the news on social media, I’m gonna be like the van man on campus, and suddenly I’m gonna get kicked out of my parking lot, so stealth and secrecy were the names of the game.

Brett McKay: Well, and it was technically not against the rules to do this, there wasn’t a rule about this, right?

Ken Ilgunas: It was kind of vaguely worded and I think I just kind of purposefully looked the other way, what’s that saying? It’s better to beg forgiveness than ask permission, and that was kind of a huge approach to almost everything in my mid-20s, so I just decided I’m just gonna secretly live in this van, so the van came with blinds and I put up this big black sheet behind the windshield whenever I was in there, so nobody knew I was in there and Duke, that’s where a lot of affluent young folks go to school, so I didn’t think any locals or campus security were thinking that one of their own was living in a vehicle, so I had that going for me as well.

Brett McKay: Okay, so you did everything on this thing, you cooked, what kind of food were you cooking in a van?

Ken Ilgunas: I’ve learned a lot about nutrition since then, so I was just eating a lot of peanut butter, cereal, oatmeal, I kind of put peanut butter in almost every meal I ate, but some of it wasn’t bad, I had a Whole Foods basically right next to my van, so I’d go there and buy a couple of vegetables, chop them up, put them in a stew, so just kind of like a vegetable stew or rice and bean burrito night, just really simple stuff. And that first semester, I was quite extreme with keeping my budget as low as it could be, I had it down to about $4.34 a day for my food costs and all my other costs, whether it was gas for the van, car insurance, whatever came to about $103 a week. So I lived on a budget of about $400 a month, which I found quite manageable, and it was all possible because of the van.

Brett McKay: Then your bathing, I guess you did at the school gym, the locker room there.

Ken Ilgunas: It was not a life of deprivation at all, I should say. I mean, the Duke gym had a sauna, a swimming pool and a sauna and a basketball court. So it’s not like I was living in complete deprivation. The library was open almost all hours, so if it was too hot or too cold, I always had a place to go. I had a really good sleeping bag. North Carolina winters don’t get too cold. And man, I slept so well there, I have a four-year-old daughter now, so I know what it’s like to be in a state of sleep deprivation for years on end, but I slept so well. One of my favorite parts of that period of my life was just waking up, ’cause I was so time-rich. I would just wake up and just slowly wake up and think and just kind of stare at the roof of my van and listen to all the birds and the bugs outside, I’d just kind of slowly wake up for an hour, that’s the biggest thing I miss about that period of my life.

Brett McKay: You talk about how the hardest thing about living in a van, so it sounds like you were living pretty good, it wasn’t… You weren’t deprived. You’re eating well. You were comfortable you had access to showers to a sauna, to a gym, but the hardest part was the social isolation, but you’re seeing people at your classes and whatnot. Why did you feel so lonely?

Ken Ilgunas: Well, one I’m an introvert, a little bit shy and things like that, so making connections out of nothing doesn’t come as easy to me as it might to others, so there was that, and then there was the whole secrecy factor. I didn’t know who I could trust with my secret of living in a van, so I just found myself telling little white lies with all these new acquaintances I had. They’d always ask me, you never know how quickly the question, Where do you live comes up until you’re secretly living in your van. It’s usually like, question number two, where are you living? And I would say I live on 9th Street, which was true in Durham, North Carolina, but they would always think I lived in the apartment complex there and not the parking lot, so. Yeah, so it was just… And grad school and college in general, can be quite lonely when you lose your neighborhood and your old friends and your family, so I think what I was going through was quite common, it was only exacerbated by the van.

Brett McKay: In Walden, Thoreau talks about the cost of a thing, and thanks to your unconventional life, you’re able to pay down your debt and you’re able to avoid new debt, but were there unintentional cost of your extreme measures that you might see now, thanks to hindsight.

Ken Ilgunas: Well at some point, I would say my 20s was a period of de-institutionalization, and what I mean by that was I was getting rid… I was just shedding off all institutional influences, whether that was your family, your neighborhood, your church, stable work, all of that was kind of being shed in the name of independence, of self-improvement, of adventure, of living your life the way you wanted to. So you’re kind of playing with fire when you shed everything, and when you live in a state of institution-less-ness, there’s a lot of wonderful things that can happen in that period. You can really see your society and your culture around you almost with fresh eyes, because you’re viewing it from the outside, and you’re really able to kind of fashion your own character outside of these institutional influences, but there’s a cost with that, and this was a period in my life where I wasn’t devoted to developing friendships, building that friend network, finding a church or a workplace. When you’re completely adrift like that, sometimes you feel a bit empty and a bit lost. I was living the life of perfect freedom. I had no debt, very few bills, I could kind of do anything I want. And that sounds like the American dream in some ways, but there’s nightmarish qualities to that too.

Brett McKay: Yeah, Aristotle talks about that. People who just live by themselves solitary, he says they are either gods or beasts, there’s a part of humanness, you miss out on when you’re not embedded in a community.

Ken Ilgunas: And I hungered for that and I just… And I didn’t go on that journey, I’d say until my mid-30s.

Brett McKay: Did people eventually find out that you were living in a van on the campus of Duke University, like what happened when they did find out?

Ken Ilgunas: Yes, they did. I kind of outed myself after a year of doing it, I wrote an essay in my… A travel writing class I was in, and my teacher, it was kind of like, I live in a van down by Duke University. And she’s like, Oh, man, you gotta publish this. This article’s gonna go viral, ’cause this was just in the height of the great recession after 2008, so everybody was in debt, there was a lot more awareness about student debt, and she thought the story of someone desperately trying to live within his means would really register and she was right.

So I wrote this article for salon.com, an internet magazine, and it just took off. So overnight, I went from completely anonymous and secretive van dueler to momentary celebrity. The next day I had NPR on the phone, Inside Edition was calling me, Rachel Ray wanted me on her show to pimp out my van, and I remember I was on the phone with a Raleigh newspaper and my hand was just shaking, shaking uncontrollably. It was exciting in a great and terrifying way, so I kinda outed myself, one of the first things, Duke University, their spokesman said, We’re prepared to help Ken find guidance and counseling. As if I was crazy.

And soon after that, a local student complained that they didn’t want to share a parking lot with someone living in it, and that’s when I felt like I was being persecuted. It felt like, Oh, they’re persecuting the van dwellers now. But Duke was kind enough, they just made me sign a contract saying I wouldn’t sue them for anything as long as I parked near the campus police station, so they gave me a new parking lot and let me finish and graduate, and when I did graduate, they passed a new parking law of prohibiting anyone from doing what I did, which is the legacy I left there at Duke University.

Brett McKay: It’s the Ken Ilgunas law.

Ken Ilgunas: They should have named it after me.

Brett McKay: Okay, so this period of your life, you call it the de-institutionalized period of your life, but recently you said in your mid-30s, you’ve gotten married, you had a kid, you’ve put down some roots in a village in Scotland, so you’re starting to re-institutionalize yourself, kind of reintegrate yourself into community life, how do you think people should balance freedom and having institutional attachments like what’s been your experience?

Ken Ilgunas: I wish I had all the answers and it really varies on the person and the culture the person comes from. Whatever it is about my ethnic background or whatever, I kinda glorify this kind of Thoreau individualistic frame of mind, whereas some of my Italian-American friends, they’re just a lot more connected to their families and don’t have those same kind of lonesome longing, so I don’t wanna say don’t do that, but just speaking from my own point of view, I do think it’s good to kind of deinstitutionalize and go on that crazy year-long or two-year-long journey where you’re kind of outside, you take a break from all those institutions, and again, I think it’s great to kind of see them anew from the outside, and to fashion your own individuality and character through experiences that no one has ever had. I think that’s an education in and of itself, and I would advise not trying to rebuild your institutions as late as I did. I remember I was 34 and I was living in a cabin in Alaska, in this park called Lake Clark National Park, and I was surrounded by grizzly bears, I’d see about 30 grizzly bears a day.

And I’m just like, What am I doing? I’m living the dream of my 21-year-old self in my mid-30s, I felt like I should have been dating and trying to find a partner and trying to find a home, and I just keep going back to these really remote, dangerous places in Alaska. So that’s when I kind of unconsciously made the decision so like, Oh, I gotta find a home. I gotta find a partner. I gotta build a family, and stuff like that, so that’s kind of the journey I’ve been on, and my journey is not over with like… I’m not religious, so I don’t have a church, I’m a writer. So I work from home in front of my computer all day, so there’s still things I want to do to kind of rebuild the institutions in my life.

Brett McKay: So maybe have a Rumspringa, like an Amish Rumspringa when you’re young, have an adventure, and as you get older, start adding attachments back into your life, but don’t wait too long. How are you doing the same, do you still have that itch to go off to Alaska go off to the wilds, how are you balancing freedom and roots as a 40-year-old?

Ken Ilgunas: Well, first of all, I think Rumspringa that should be the name of someone’s memoir, that’s an awesome title for a travel memoir or something. Yeah, yeah. I’ve got a four-year-old daughter. I moved into a very shoddy house that needed a lot of work, so I’ve just been living the domestic existence for a few years, and as my wife has a much more stable job than I, I was kind of a primary caretaker for my daughter for a couple of years, and there was an extreme sense of loss. Of course, I gained a lot, I gained a family, but it felt like I almost lost a part of myself, and I remember I had these weird ideas of creating an effigy of myself and burning it over a bonfire just to kind of wish him well and say goodbye. But things get easier as a dad and things are getting a lot easier for me now, and… Yeah, I feel like that kind of wilder half of myself, he’s still there, he’s just in a state of hibernation, and I look forward to the day when I can let him out again, a bit.

Brett McKay: Yeah, maybe you’ll be like that guy who lived in his Subaru he’s in his 70s, and he’s living in a Subaru in the northern… That’s gonna be you when you’re 70.

Ken Ilgunas: That’s gonna be my Rumspringa sequel memoir to Walden on Wheels.

Brett McKay: Exactly. Well, Ken, this has been a great conversation, where can people go to learn more about the book and your work?

Ken Ilgunas: Just go to my website, kenilgunas.com, you can sign up for my free newsletter. I won’t overburden you with that. That’s just kind of a once a month or once every two month thing, and you’ll see all my books on the page.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well, Ken Ilgunas thanks for you time, it has been a pleasure.

Ken Ilgunas: It’s been my pleasure. Thanks so much, Brett.

Brett McKay: My guest here is Ken Ilgunas, he’s the author of the book Walden on Wheels. It’s available on amazon.com, you can find more information about his work at his website, kenilgunas.com, also check out our show notes at aom.is/waldenonwheels, where you’ll find links to resources where we delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM podcast. Make sure to check out our website at artofmanliness.com, where you can find our podcast archives. And while you’re there, make sure to sign up for our newsletter. We’ve got a daily option and a weekly option. They’re both free. It’s the best way to stay on top of what’s going on at AOM. And if you haven’t done so already I’d appreciate if you’d take one minute to give us a review on Apple podcast or Spotify it helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or a family member who you think will get something out of it. As always thank you for the continued support. Until next time it’s Brett McKay, reminding you to not only listen to AOM podcast, but put what you have heard into action.