Last week we discussed Edwin Friedman’s theory of what makes groups dysfunctional.

Friedman laid out his ideas in A Failure of Nerve and based them on the “Bowen family systems theory.” He posited that many modern families, organizations, and even nations have an emotional system characterized by “chronic anxiety” — a high level of tension/nervousness that the group experiences as a whole.

Friedman observed five characteristics common to all groups with chronic anxiety (see the previous article for an explanation of each):

- High reactivity

- Herding

- Blame displacement

- Quick-fix mentality

- Lack of well-differentiated leadership

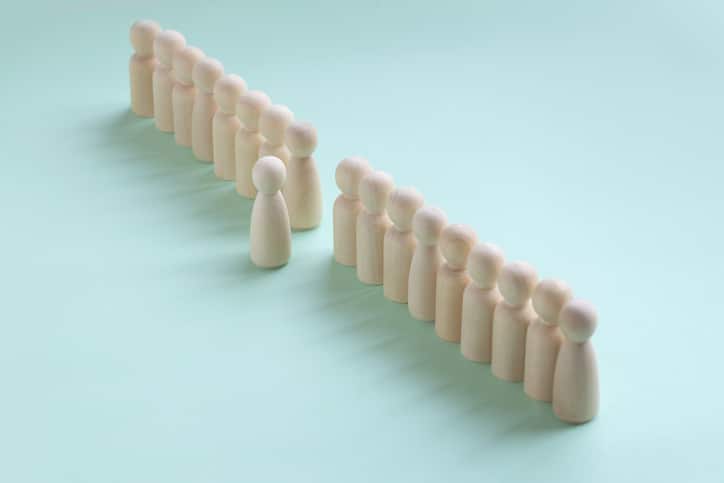

For Friedman, that last characteristic — lack of well-differentiated leadership — was the most significant factor that leads to and drives chronic anxiety. A lack of well-differentiated leadership creates uncertainty and disorganization. Uncertainty and disorganization produce chronic anxiety. As anxiety increases, characteristics like high reactivity and herding begin to rise, elevating the anxiety even further. A vicious circle is formed.

To quell chronic anxiety in a group, someone needs to step up and become a well-differentiated leader.

Below we unpack what that looks like.

Differentiation in Bowen Family Systems Theory

Friedman based his idea of a “well-differentiated” or “self-differentiated” leader on the concept of differentiation in Bowen family systems theory.

The psychiatrist Murray Bowen believed that many of the problems people encounter in life are due to their inability to differentiate or separate themselves from their family’s emotional ecosystem. Here’s an example:

A child grows up in a family where his dad has a bad anger problem; when his father loses his temper, he becomes emotionally abusive. This creates an ever latent layer of chronic anxiety in the family. To deal with that anxiety, the mother tries to ensure that her kids never annoy their father. She constantly tells them to stay quiet and not bother him.

This boy routinely calibrates his desires based on his parents’ emotional unwellness. He learns that if he states what he wants or needs, Dad might get mad, and if Dad gets mad, someone will get hurt. So he just keeps things to himself.

The child develops a tightly fused relationship with his mother and father. His sense of self is based largely on what they want from him, and he never forms his own differentiated sense of self. His self, such as it is, is created by what he thinks will maintain family peace and order.

As an adult, this man carries his lack of self-differentiation into other parts of his life. He isn’t able to be assertive. He has a hard time standing up for himself at work. He struggles to say no. He’s a people pleaser, even though it makes him miserable. Women might find him attractive in the beginning because he seems so attentive to their needs, but they later find his lack of self contemptible.

The idea of pushing back on anything fills him with anxiety, because in the recesses of his mind he still thinks, “If I cause a stir, Dad will get mad, and someone will get hurt.”

Bowen would say that for this man to become emotionally healthy, he needs to learn how to differentiate and disentangle himself from the chronic anxiety of his family and develop a more autonomous self.

Differentiation isn’t an endpoint in family systems theory. Bowen didn’t think you could ever achieve “differentiation nirvana.” Instead, differentiation is a goal you spend a lifetime journeying towards. It’s a process.

What Is a Well-Differentiated Leader?

Friedman took this idea of differentiation and applied it to leaders in all kinds of groups beset with chronic anxiety.

For him, a well-differentiated leader is able to escape the anxiety of a group while still being connected to the group. He can maintain a “non-anxious, well-principled presence” in the face of the stressors swirling outside and within the group. Rather than getting caught up in the same dysfunctional behaviors which plague the group, he stands apart from and above the dysfunction.

In short, a well-differentiated leader can be a part of a dysfunctional group without its chronic anxiety affecting him.

What does this look like in action?

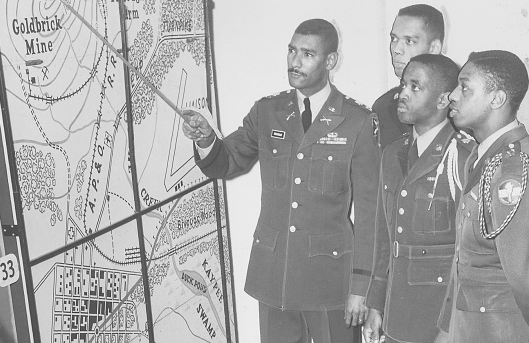

Friedman lays out some principles. The well-differentiated leader:

- Organizes the group around strengths as opposed to weaknesses.

- Is more concerned about his own growth than the growth of others in the group.

- Encourages other group members, by his example, to take responsibility for their own problems and emotions.

- Works with motivated people instead of spending all his time trying to motivate maligners.

- Responds to problems in an objective manner instead of reacting emotionally.

- Is clear about his own personal values and goals.

- Can take a stand in the face of intense pressure in an emotional system.

Some of this advice seems to fly in the face of modern dogmas about good leadership. “A leader is more concerned about his own growth than the growth of others in the group?!”

But the idea here is this: by prioritizing your own effectiveness and emotional strength, you become a rock and backbone for the group. An oasis of stability and calm in an otherwise floundering, tension-filled community. You become the group’s leaven, and your non-anxious, principled presence can rub off on others.

When members of the group see that a differentiated leader won’t join them in their chronic anxiety and isn’t even going to do much to soothe it, they’ll start soothing themselves. Ideally, these individuals will begin doing their own differentiation work. The more group members who differentiate, the healthier the group becomes. People learn that they can do more as a group when each member has a distinct sense of self.

A vital point Friedman makes is that well-differentiated leadership is more about emotional presence than behavior. There aren’t any social hacks you can use to display your status as a well-differentiated leader. You simply have to spend a lot of time “sorting yourself out,” as Jordan Peterson puts it. By showing up as a sorted-out self, you start a chain reaction where the group can begin sorting itself out as well.

Expect Sabotage in the Face of Differentiation

Dysfunctional groups, while dysfunctional, can still provide comfort to their members, particularly emotionally unhealthy members. Some people like it when things are highly reactive and volatile. They find it “exciting.” What’s more, immature people often benefit from chronic anxiety in a group, as the herding principle causes other group members to direct their energies towards accommodating their needs.

A well-differentiated leader can upset that dysfunctional-but-familiar equilibrium. Instead of reacting, he avoids getting sucked into emotional and polarizing debates. Instead of compromising the potential of the majority to thrive by changing the group’s structure or culture to cater to a lone exception, he asks the exception to accommodate to the rest of the community. Instead of adapting the mission to the lowest common denominator, he asks that denominator to adapt to the mission.

This can upset emotionally unhealthy people. In response, Friedman argues that the chronically anxious will often begin sabotaging the well-differentiated leader. He will be accused of being power-hungry and unempathetic. Passive-aggressive mucking up of group operations will occur.

Friedman argues that sabotage is a sign that the well-differentiated leader is on the right track.

The key for the well-differentiated leader is to maintain his non-anxious presence even in the face of sabotage. Ideally, the example of the well-differentiated leader will nudge emotionally healthy individuals to start taking responsibility for their own lives. If it doesn’t, the well-differentiated leader possesses the nerve and courage to kick emotionally immature members out of the group for the sake of the larger community.

How to Become a Well-Differentiated Leader

Because Friedman died before he could complete A Failure of Nerve, he never fully fleshed out his ideas on how one could become a well-differentiated leader. He did leave some hints, though:

Work through differentiating yourself from your family. If you’re part of a “fused family,” you may never have developed a distinct self, and as mentioned above, the inability to differentiate yourself from your family can carry over to other parts of your life.

A man who cannot set boundaries with his parents isn’t likely to be able to set boundaries with his subordinates and associates.

To start setting boundaries in other areas of life, you must first practice setting boundaries with your kin. You have to learn to be an individual while still being a part of your family. It isn’t easy, but it is possible.

Focus on your personal development first. A lot of leadership advice these days is about putting the needs of those in your group above your own. Friedman argues that’s backward. A differentiated leader will prioritize his own personal development. Doing so inspires those around them to take responsibility for their own personal growth and start working on it.

Don’t make belonging to the group your sole source of identity. Doing so sets yourself up for getting sucked into the group’s anxiety. If your identity is tied up with the group, you’ll be more invested in ensuring everyone is pleased and happy. This is a recipe for stress and burnout. Distribute your sense of status across several “pots,” and maintain a bit of detachment from the groups you lead.

Have a support system outside of the group you lead. You need people who can provide support and a neutral third-party point of view of the problems you face. Friends, mentors, and therapists can provide this.

Make sure you’re not just talking to people whose opinions are already colored by the chronic anxiety of the group you lead.

Have a bedrock of principles and clear long-term goals. Know what you’re about and what you’re trying to do as a group leader. The clearer you are on your principles and long-term goals, the less likely you are to be tempted to implement the short-sided, emotionally reactive, quick-fix ideas forwarded by your group’s chronically anxious members.

Practice deep breathing, prayer, or meditation. The key to being a well-differentiated leader is maintaining a non-anxious presence in the face of chronic anxiety. Relaxation techniques can help with that.

Make the hard decisions. Friedman observes that the poor leader frequently puts off making hard decisions by falling back on the need to gather more data. It may look like he’s being responsible, but it’s a way to procrastinate making a difficult choice. The postponement of decisions creates uncertainty, uncertainty creates anxiety, and anxiety creates dysfunction.

If the same question keeps bringing the same data, it’s time to pick an option and pull the trigger. Get into the practice of making hard decisions, as quickly as possible. This is the crux of what separates poor leaders from well-differentiated ones.

Maintain your sense of humor. Over-seriousness is a symptom of highly anxious people and groups. Friedman believed a well-differentiated leader fosters a certain lightness in his community by maintaining a sense of humor, even in the face of a crisis. Humor keeps the system loose and thus open to new ideas and solutions.

Differentiation isn’t easy. It’s a process you’ll have to work on continually for the rest of your life. But the rewards are well worth the effort. As you differentiate and become an individual, your own life will become better and more flourishing, while simultaneously improving the lives of the people you lead — whether they’re in your family, your business, or your church.

To become a leader, first become a self.