Once again we return to our So You Want My Job series, in which we interview men who are employed in desirable jobs and ask them about the reality of their work and for advice on how men can live their dream.

When people think about diving, tropical vacations and swimming next to brightly colored fishies comes to mind. But there’s a grittier world of diving: commercial or deep sea diving. These are the guys that keep the world running above the water, by putting in the hard work below it. Ron Null has been a deep sea diver for almost 30 years and he sounds like exactly the kind of man every employer is lucky to have on the job. Thanks for taking part in our interview, Ron!

1. Tell us a little about yourself (Where are you from? How old are you? Where did you go to school? Describe your job and how long you’ve been at it, ect).

I’m originally from San Diego County, CA.

Following high school, I fell into the diving business through a friend who had spent time first as a Navy diver, then as a Reservist. He did commercial diving work around the San Diego harbor and connected me with a job. Later, due to insurance reasons, I enrolled in a commercial diving vocational training school to formally obtain a certification. So, with the combined time before and after formal training, I’ve been at this for just about 30 years. I began in the harbor market on piers and pilings, moved into the offshore oilfield on platforms and pipelines for about 15 years, then migrated into civil work on dams, bridges etc.

2. If a man wishes to become a deep sea diver, how should he best prepare? Are there schools that can train you?

The best way to prepare is to be as well-rounded mechanically as possible. Polish your common sense. Develop confidence without arrogance. Stand by your decisions. Worry less about competing with others and more about elevating your professionalism. If you choose to do this as a career, be the best at it that you can be. Don’t dabble in it just because you can earn a few bucks, because that is an unsustainable motive and you’ll eventually either be found out as your abilities will get dull through complacency……or, you’ll kill yourself.

3. What kind of jobs do deep sea divers do?

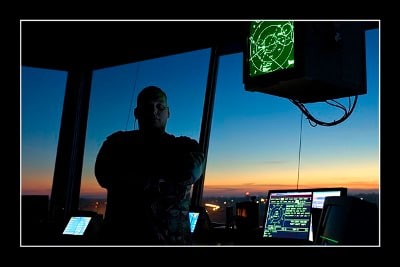

Manual, unglamorous labor and tasks ranging from the most strenuous grunt-work to the installation and repairs of relatively technical instrumentation and just about everything in between. If it can be done above water, at some point it will need to happen underwater.

Inspection divers are often the ‘eyes and ears’ for engineers and technicians, acting like organ-grinder monkeys operating at the command of someone else that directs the diver to obtain information that that person is unable to obtain for themselves.

Construction divers perform just about the same kind of concrete, steel and timber construction that you get on other kinds of small, medium and large civil jobs, the only difference being that the environment is different. It’s the same kind of construction tasks like concrete forming, welding and cutting, rigging etc. with the additional factors of wearing a helmet and rubber suit, invariably in marginal to absolute zero visibility, in cool to downright cold water for sometimes hours on end, often deep and what can mess with your head is being a long way from the safety of the surface if you allow your mind to run away with your thinking. Sometimes in current or tidal flows, sometimes with the pressure of time or budget constraints, sometimes in miserable locations or weather conditions. Often the working environment is uncomfortable, and it’s challenging to maintain enthusiasm if the job at hand is mundane or boring, physically exhausting, or if the decision makers directing the operation just don’t get it or insist on it being carried out in what you know is not exactly the best way, but their way.

4. How competitive is it to land a job as a deep sea diver? What sets a candidate apart from others when he’s applying for a position?

Anybody that has money can pay the tuition and attend a diving school. In spite of what the dive school recruiting salesmen or “career counselors” would have you belive, they don’t turn anybody away that has money. They are businesses after all.

Following successful completion of a training school, the entry-level position is called a Dive Tender or “Tender” for short. The tender is essentially an apprentice who works as part of the above water team that supports the diver working below. A tender works in this capacity for a period of time during which he is supposed to keep his eyes and ears open to learn the business. Learn the way systems, tools and equipment operate. How to properly send tools to the diver, how to stay aware in a dynamic industrial environment, and how to carry out directions as part of a team or cohesive group with a common goal. During his (or her) time as a Tender, the supervisor will often grant the tender dives from time to time to carry out simple tasks in order to both give the tender some water time as well as possibly utilizing the tender as an interim diver in order to save a more skilled diver for some upcoming task that requires more talent. Once the tender has spent what has been determined to be a reasonable amount of time learning his craft, he is then declared to be “broken out” as a full fledged diver, allowing him to be assigned to jobs with the title “diver.” During this time as tender, it is also the time of determining self-washout or attrition. Few are cut out for the career. While you are a tender you come to find out that the lifestyle is not exactly what they painted when you were in dive school or watching the Discovery Channel. That is the time to go back to bank teller or trucking school. Or, make your parents happy and save some of those tender earnings and go to college and get a degree.

The tender phase is a subjective one. The duration that one toils in this most thankless and arduous role is as determined by one’s luck in being in the right place at the right time as the rate at which one learns the trade. As with anything in the competitive free-market, supply and demand plays as much a factor as talent and enthusiasm in break out. Following hurricane Katrina, graduates of dive schools were breaking out as divers sometimes in just a couple of months. This was to satisfy a need by diving companies to satisfy the windfall workload. And, while I understand the profit-sided rationale for this, I have little endorsement for this practice. The best, most well-rounded divers I have ever worked with had learned their craft in a controlled and methodical system of experiences and opportunities to witness and participate as a tender before being thrust into the demands of delivering quality workmanship as a diver. It is an injustice to shortchange someone that plans to be in it for the longhaul in this way. Because, if the inexperienced is suddenly asked to achieve at a level that they are not fully prepared or qualified for, their failure or paltry success will set their reputation in a direction that it probably won’t ever recover from. There are also those who “break themselves out” by buying all the gear while they work as a tender for one company, then heading down the road and selling themselves as a “diver.” With the modern advent of cell phones and email, this has gotten to be less of an issue since the industry is so small that just about everyone can check someone’s reputation with just one or two degrees of separation. Just about anyone you find yourself working with has worked with someone else that you’ve worked with. It doesn’t take more than a couple of minutes to find commonality in the diving business. For this reason, reputation is something to be careful with. Yet, because the work is down deep in the dark, there will always be the divers that can bullsh**t their way for a long time on self-selling rather than performance. But, eventually they run out of companies where nobody knows them.

The “break out” diver is the most dangerous time for anyone in this business. It takes a large measure of self-control to keep an ego in check once you have been labeled a “diver.” Many break out divers develop the swagger and the big headed attitude that they now know everything and that no one can tell them anything. Many never recover and stop learning and perfecting their skills. Indeed, the diving industry is populated at all levels by huge egos. In my experience, the divers that I prefer to work with are those who are silently competent, humble enough to perform the menial task without being asked if they see that it needs doing, pass along tips and hints to the other divers and younger members of the crew, and are always looking to find a better way to do things.

5. Are deep sea divers employed by a company? Or do they do freelance work, signing up for different projects?

Both. The larger diving companies (those that primarily stay within the offshore oil market) maintain company divers. When I first started, there was more acceptance of the “freelancer.” Nowadays, the big players prefer to invest training and time into divers that will stick around and be counted on to be ready to go to work when called upon. But, as with any business, if the company can’t deliver, you gotta go where the work is.

The civil or so-called “inland” diving market has generally smaller companies. The larger of which maintain a similar attitude of wanting to keep a core group of divers. Some of the smaller “mom and pop” companies will expand and contract to fit their job loads at any given time, be it economic or seasonal. This allows many divers to shop themselves around and make a decent living as a transient employee.

6. What is the best part of your job?

The variety of jobs, tasks and locations. I have had some great jobs over the years: some very satisfying salvages, demolitions, construction projects and year-to-date earnings.

7. What is the worst part of your job?

Sometimes the travelling and living on a boat or in a hotel can get old if it goes on for a long time without a break. Being cold can suck. Divers that wear all the deep-sea diver t-shirts and belt buckles and turn the job into their only identity can be kind of comical.

8. What’s the work/family/life balance like?

As with any career, it’s pretty much what you make of it. It does take a special person to be the spouse of a professional diver. I don’t know this to be a statistical fact, but I do feel that anecdotally there is a larger than average divorce and break-up rate for divers. Owing primarily to the time away from home and the ups and downs of personal economics. But, conversely, it can be very liberating to work for a chunk of time, then have a period of time off, rather than the Monday thru Friday with weekends off then back on Monday. The balancing act is maintaining the work coming in and not finding yourself with too much time off.

9. What is the biggest misconception people have about your job?

“What’s the deepest you’ve been?”

“Do you ever see any sharks?”

“You guys are rich, right?”

10. Any other advice, tips, or anecdotes you’d like to share?

Learn to communicate and convey information accurately and objectively, without drama or sensationalism. Remember that no matter how deep and dark and alone your work is, someone will eventually see it or inspect it. Don’t cut corners to make yourself look faster or better at accomplishing something. Do it right. You may be by yourself down there while you’re working, but you should keep up your ethics.

Experienced supervisors and senior divers know that you can tell everything you need to know about how a diver works when he’s on the bottom by watching how he works on the deck. All of his efficiencies, strengths and ethics are revealed if you just watch him work ‘in the dry.’ If he moves slowly, tentatively or with what is observable uncertainty, or if he has to make four trips to get the right tool, or if he stands and stares at the problem and just can’t quite figure it out, or if he tells you the job is done and you can look right at it and see that it wasn’t done correctly…….that is how he is working when he gets over the side and you’re hearing him down there over the dive radio and envisioning what he’s doing.

Every working dive and every day is an investment in the next dive and a future day. You can either waste it, or you can learn and build off of it. That’s part of a thinking man’s professionalism. Make every dive count and make every day count.

If you want to always be considered a “good diver” and get the work, make the company look good and make your supervisor look good. Supervisors keep guys around that make their life easier, not the guys that require constant re-assurance and dramatics.

Don’t allow anyone to convince you to do anything that in your heart you don’t think you should do or is not safe. Think about everything that you are asked to do, don’t just do it. Be a thinking man. Just because the guy that you work for has many years more under his belt doesn’t mean that he necessarily knows what is best for your safety. Own your own ass.

Set up the next diver in rotation and they will set up unto you. That goes both for the good and the bad. Get a reputation as a diver who consistently leaves a mess for the next guy and you’ll find less and less work as your career moves along.

Enter the water like you have your s**t together and are going to take care of business and get the job done. Exit the water strong, like you made things happen.

Always get the money.

Tags: So You Want My Job