Editor’s Note: This is a guest post from Stephen Fortenberry.

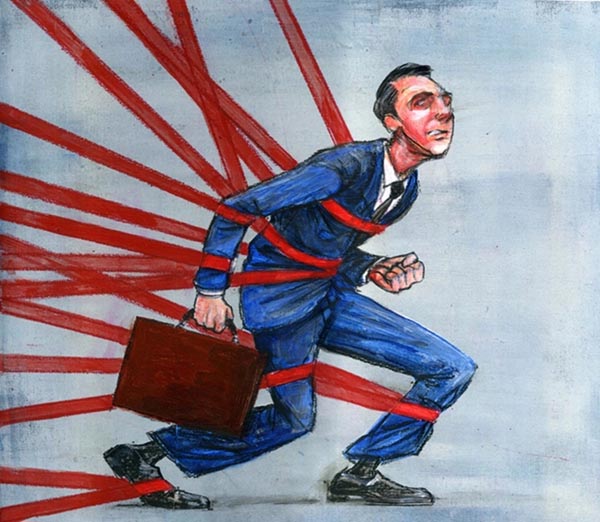

If you had asked those of us who are now in the workforce, to describe our ideal job or career path back when we had just graduated from college, many of us would have talked about being our own boss, or at least being part of a small team of decision-makers. The current reality for most of us, however, is that we find ourselves as “anonymous” members of large bureaucratic organizations, and possibly rather frustrated by that fact. We feel like a cog in the wheel, crushed by the weight of organizational machinery, and powerless in the face of externally-dictated policies, procedures, and red tape.

For those who share in this situation, I offer two pieces of good news.

The first is that bureaucracies are not always as bad as we make them out to be, and can actually have their upsides, including the fact that a well-run organization can accomplish greater good in the world than an individual could on his own. Being an employee rather an entrepreneur has its advantages as well; among other things, it can in fact be nice not to have the entire weight of an endeavor’s success sitting on your shoulders.

At the same time, the perception of being powerless within a bureaucracy isn’t entirely accurate; while it may seem difficult at times, it is possible to achieve feelings of agency within its strictures. Below I discuss how to do so, and operate with effectiveness, and even fulfillment, when you’re part of an organization.

Keep the Core

While organizations large enough to require a bureaucracy are formed for a key purpose, many individuals feel that they are pulled in so many directions that they are left scattered, and unable to focus on it. To be effective, you need know what the key purpose of the organization actually is, know how your specific role fits into this purpose, and orient your efforts around this core mission. In other words: “Put First Things First.”

A helpful practice is to distill your understanding of your specific role into no more than three thoughts that serve as lenses to filter your efforts. Your organization quite likely has a mission statement, and while this is a good starting point, such statements are generally too broad, too vague, and too laden with buzzwords for individuals to effectively apply them in practice. Instead, find your own way to describe which of your responsibilities contribute most to the achievement of the organization’s purpose.

As an example, here are the three thoughts I feel frame the core mission of what I should be doing as a high school math teacher:

- Have a positive influence on students by developing appropriate, professional relationships

- Consistently provide high-quality mathematics instruction to students

- Support other teachers’ efforts to develop relationships with students and provide quality instruction

Once you have refined your set of key ideas, use this list to direct your efforts through self-discipline and personal effectiveness. Find ways to maximize those activities that contribute directly to the achievement of the core mission, and minimize those that do not. Note that the word “minimize” was intentionally chosen, since it is virtually impossible to eliminate all activities that do not fit with the core purposes of your position. For example, you must still complete that paperwork you suspect will be going into a “black hole”; as we will discuss, working with the system is part of playing the long game and gaining influence.

However, you should not spend any more time and effort on such tasks than is required to complete satisfactory work. Devote the cream of your energy to those tasks impacting what you know to be truly important.

Work (WITH) the System

Once you have developed a filter to direct your purposes within an organization, your thoughts should necessarily turn to how to achieve these purposes. As you do so, it is important to remember that it is not your system to control, but it is your system to work with. Keeping this in mind will help you to not give in to the temptation of believing that everything would be better if you ran things. Such a thought is dangerous for two reasons: 1) it does not align with the reality that you don’t run things, and 2) it dismisses the value of the organizational wisdom developed through countless years of collective practice. Accepting this does not discount the overall need for improvement, or mean that you are not the one to affect change.

However, it does mean that you should respect, and seek to understand, the reasons behind the practices you see. Moreover, accepting the reality that you must generally work within a system reduces the exasperation that is inevitable when we expect the world to work our way. Once this is accepted, you should consider both how to effectively achieve your core purposes directly through your own activities, and indirectly through the development of influence within an organization.

Get Action: Direct Impact

Almost all of us have some set of tasks that we are expected to perform, and for which we can be held almost solely accountable. As a teacher, the best example would be my actual delivery of lessons in class. Yes, I may need resources from my school district and help from other teachers. However, at the end of the day, it is me standing in front of students either delivering a quality lesson, a mediocre lesson, or a poor lesson. In your case, it may be documents, presentations, or other products you are delivering internally within the organization or to an external customer.

Consider not only the big stuff you have direct control over, but the small stuff as well. Just do a thought experiment that considers all the impacts, no matter how small, of your core tasks being done well, and then the same tasks being done poorly. You are almost sure to find that what you do matters; even if it does not change the world in the same way the high school, or college, version of you once envisioned.

Whether the tasks are big ones or small ones, there is sure to be something, or some things, that you control to a great extent.

In a bureaucracy, it is also just as sure to be the case that there are policies and procedures governing the execution of the tasks for which you bear ultimate responsibility. It can be very tempting to fall into the trap of making the established bureaucratic policies and procedures the excuse for your failure to perform quality work, or achieve your core purpose. However, rather than following that path, embrace the mantra of the Art of Manliness: Get Action.

First, you should consider whether the bureaucratic policies and procedures truly limit your ability to accomplish your core purposes, or if they simply require that you modify your approach to accomplishing the objectives. In other words, is what is holding you back a matter of preference or substance? If it is merely a matter of preference, then the best path forward may be to accept the method put forward, and execute your core tasks as efficiently as possible. Doing so will help you avoid unnecessary friction and, as we will discuss later, help you gain greater influence in the long-term by avoiding unnecessary complaining.

If you judge a disagreement over directives to be a matter of substance, or that what you are being asked to do defies common sense, you may simply need to find a way to assert your disapproval in a tactful manner (more on this below). It may be that your proposal will be accepted, or at least that you will gain some satisfaction from having voiced your opinion.

Alternatively, you may want to reconsider the interpretation of what is being called for in the policy or directive. In an effort to protect ourselves from any risk, we too often look for the most restrictive interpretation of a policy so that we can simply blame the policy if anyone ever finds fault in our actions. This is not an invitation to throw out all considerations of policy and act in bad faith. However, it does mean that, when you are confronted by a requirement that defies common sense if interpreted in the most draconian of terms, you should work to find an interpretation that allows common sense to take its proper place. Doing this could require that you increase your personal agency since it may necessitate that you take responsibility for your interpretation of policy rather than relying upon an explicit statement of whole-hearted approval from a manager. Realize that it is sometimes better to ask for forgiveness than permission, and keep in mind that a good manager typically values the common-sense, practical implementation of policies and procedures made in good faith even if they cannot explicitly endorse it.

Get Influence: Indirect Impact

In addition to those things that fall directly within your responsibility, there are many other things over which you have very little formal control. Ironically, it is often the practices over which I do not have direct control that have impacted my attitude toward a job the most.

The first step to effectively dealing with such matters is to admit the truth that you cannot control determinations related to those subjects, and that you can only hope to have some level of influence. The next step is to develop influence, which is far more of an art than a science. The most essential principle to keep in mind when developing influence is that people matter, so it is vital that you act like they matter. Yes, it is important to have good ideas and develop logical arguments. However, it is ultimately other human beings who are making the final decisions in organizations.

Given this, when seeking to influence a specific decision I attempt to balance how hard I am willing to “fight” for my position with what I consider to be the true measure of influence: whether people, who don’t really have to continue listening, want to continue to listen to the words coming out of my mouth. By listening, I mean that they actually contemplate what you are saying and honestly consider incorporating your recommendations into their decision. I do not mean that they simply thank you for your “candor,” and do nothing with your input. As was emphasized above, we are focusing on decisions that are made outside of your direct control. Hence, if the person or group that is making a decision doesn’t want to listen to you anymore because of previous interactions, then you cannot impact any decisions. Consequently, there are very few arguments that are worth sacrificing a workable relationship with a decision-maker, or group. Beyond this guiding principle, the following ideas are some that I try to keep in mind with respect to developing influence:

Trust takes time. Trust is the most important ingredient of influence. Do not expect to establish trust through a few interactions, or through false sincerity. Trust, especially in a bureaucratic setting, is established through genuine consistency that others can rely upon. This includes both personal interactions, and others’ observations of whether you competently perform the daily tasks within your control. Ironically, how you’re performing in your bigger, more purpose-driven tasks, is often noticed less than whether you complete the little administrative stuff — like whether some form was filed on time — because it’s more readily observable and quantifiable. No matter what you’re working on, you may not even know that you are being observed, which is yet another reason to consistently take care of your daily duties.

People also really do value when you make their jobs easier, and it often doesn’t take you much, if any, extra time. Who do you think a decision-maker wants to listen to: 1) the person who usually misses deadlines for the paperwork that doesn’t really matter but has to be done, or 2) the person who consistently takes care of the mundane tasks without being told?

“Never complain; never explain” . . . and never, ever complain about things that are your responsibility. The maxim “Never Complain; Never Explain” is excellent advice in general, and even more so in bureaucracies where there is a constant temptation to attempt to relate to everyone around us by discussing how much we all dislike certain parts of our job. While some venting is necessary from time to time, it should be kept to a minimum and practically eliminated from your conversations with your supervisors. Your supervisor is likely aware of many of the systemic things that bug you because the last five of your co-workers they spoke with complained about those same things without offering any solutions. Be the one who can relate to others without complaints; broaden the range of subjects you can converse on.

If you must complain, be the one who doesn’t offer a complaint without tying it to a constructive solution. Most importantly, never ever complain about things that are your responsibility. For example, as a teacher, I should never complain that my students are not motivated, because a large part of my job is to motivate students. When you make complaints of this nature, you are simply indicting yourself.

“Don’t look too good, nor talk too wise.” While practically all of the poem “If” provides excellent life advice, this phrase is especially important when presenting an idea. If you present an idea in a manner that even insinuates it is so good that no reasonable person could possibly disagree with you, you are inviting disagreement. This is true even when you have an exceptionally good idea because condescension is a universally despised attitude. Moreover, it is highly unlikely that your idea is so complete that it leaves no room for improvement. A sense of humility is necessary and proper, and should be conveyed.

Different positions have different priorities — as it should be. Another source of frustration that is often faced when attempting to influence a decision vitally important to your role is finding that it is not a chief priority for others. This is especially true when you are seeking to communicate the impact of a decision, or current practice, upon your core mission to a supervisor. Too often, I have been taken aback by the realization that a supervisor has not given a great deal of thought to things that impact my ability to achieve my key responsibilities.

However, I have come to realize that this is proper and necessary. Even if my priorities are properly aligned, only someone actually in my position should be expected to have priorities similar to mine. It should also, however, not be completely surprising that people in positions similar to your own do not lend the same significance that you do to all issues. Instead of chalking up someone’s inability to immediately embrace the importance of a decision to their lack of concern or aptitude, be prepared to explain its significance. Even better, be prepared to explain its significance in the context of their priorities. Considering their priorities beforehand is also a good check to see if they are even the right person to seek help from when addressing an issue. If your issue is unrelated to their priorities, find someone whose priorities do relate.

Know not only who to talk to, but when to talk to them. As discussed above, it is important to understand the priorities of others, and allow this to guide who you choose to speak to. However, it is equally important to consider the time and setting for discussions. With timing, first consider when you are personally most open to discussing a subject that is important but wasn’t at the forefront of your mind. In other words, account for human nature. For jobs with a standard Monday to Friday schedule, this should rule out starting a big conversation first thing Monday morning about that important thing you thought about all weekend, or starting a conversation Friday afternoon about that thing you had meant to talk about all week. On Monday morning, people are trying to get back into rhythm. Friday afternoon is a time to wrap things up, and make it to the weekend. At other times, gauge their body language or tone before launching into your “great” idea.

Also, consider the setting for a discussion. Asking a specific question about a policy you care deeply about in front of a large group often does not produce the best results. It generally frustrates those who don’t care about the topic as much as you do, and makes them less open to any future comments you have on other topics. It also can force a manager to give a more restrictive response than you would receive in a private conversation, which allows for more nuanced discussion and greater compromise. Give preference to productive private and small group discussions, rather than to large group “soap box” speeches.

Conclusion

There are sure to be days where you, and I, have trouble seeing the potential value of being part of a bureaucracy. However, it is my hope that you have found this discussion relevant, practical, and encouraging. While working in a bureaucracy may not often reveal opportunities for “heroic” action, the consistent, high-quality performance of your everyday duty adds up and does make a difference. Do not undervalue the ability of an individual to positively impact a system, even a large bureaucracy. As you shape the bureaucracy for good, through the effective achievement of your daily tasks, that becomes a force multiplier — increasing your personal fulfillment, as well the positive impact of your individual influence, and that of the organization, on others.

___________________________

Stephen Fortenberry is married to an incredible woman, Kelli, and father to three wonderful boys. After working several years as an engineer for a large corporation, he switched careers to become a high school math teacher. He has just finished his sixth year in public education and couldn’t be happier with the switch. He also enjoys running, strength-training, gardening, building furniture, golfing, and being part of Scouting with his oldest son (Christopher).