Resources Related to the Podcast

- Andrew’s latest book: The War Before the War: Fugitive Slaves and the Struggle for America’s Soul from the Revolution to the Civil War

- “Harvard’s Long-Ago Student Risings“

- Wikipedia entry on the history of Harvard which starts with the quote Andrew referenced in the show (“dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches…”)

- Art of Manliness Podcast #351: The Surprising Power of a “Useless” Liberal Arts Education

- Podcast #656: The Hidden Pleasures of Learning for Its Own Sake

Connect With Andrew Delbanco

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript!

If you appreciate the full text transcript, please consider donating to AoM. It will help cover the costs of transcription and allow other to enjoy it. Thank you!

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to the edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. A lot of students are actually going to college as the waiter and the credential that’ll help them get a good job. But as Andrew Delbanco, professor of American Studies at Colombia University argues in his book, College: What It Was, Is, and Should Be, higher education was developed for a different purpose, one it should fight to maintain. Today on the show, Andrew shares how we decided to write his book to understand more about the history, nature and value of an institution which has come under increasing pressure in the modern age. Andrew describes how America’s earliest colleges were founded as places where students can learn from both their teachers and from each other, and thereby develop a capacity to grow in character, serve others, live a good life, and even face death. Andrews explains why colleges have largely abandoned this mission, and makes the case for why a broad not entirely specialized liberal arts education remains relevant in an age in which the ability to grapple with life’s big questions is as crucial as ever. We also talk about the difference colleges and universities, and no, they’re not synonymous. Why a perspective student might choose the former over the latter. And what other things those contemplating where to go to school should consider when making the decision. After the show is over, check in our show notes @aom.is/college.

Brett McKay: Andrew Delbanco, welcome to the show.

Andrew Delbanco: Thank you. Glad to be here.

Brett McKay: So you got a book published over a decade ago. I can’t believe it, it seems like not that long ago, called, College: What It Was, Is, and Should Be. What’s the impetus behind this book? And what did you start noticing in colleges and universities? ‘Cause this is your business, you’re a professor, that caused you to take a look at the history of colleges to see maybe there’s something from the past we can learn on how to improve the college experience.

Andrew Delbanco: Well, my impression, most faculty members are hired to focus on a special subject, engineering or English or whatever it may be. And then they wake up one day and they find they’ve spent 10, 20, 30 years, in my case, more than that by now, inside an institution that they don’t know very much about. And I began to feel that I wanted to learn something about where the institution in which I spent my life, first as a student, then as a teacher, came from. Every institution has a history, and usually we can learn something about where we are by figuring out where we’ve been. So I just got curious about the history of this thing that we call College, and I began to read about it, educate myself about it. And so I guess one answer to your question is just intellectual curiosity. The other one is that I think there’s a general feeling, certainly it was there on my part, that this is an imperilled institution. It’s a fragile institution. There’s a lot of pressures on it from all kinds of directions, cultural, economic. And I think we have an obligation to understand its value and to defend it and to try to see that it has a fruitful future. So that’s something like an answer to your question.

Brett McKay: Yeah, you wrote this book right around the time of the Great Recession, and there’s a lot of, I guess, hand-wringing and concern about students graduating college with enormous amounts of debt and there’s no jobs. And we’re still having that conversation today. And so, yeah, that’s one idea. We typically think of college as, “Well, it’s a place you go so you can get a job.”

Andrew Delbanco: Right. Well, look, the student debt problem is a real problem, but there’s also a lot of misunderstanding about it. A great deal of student debt is accrued in graduate school. A great deal is accrued by students who are attending for-profit so-called universities, and I use the term “so-called” because I think a lot of for-profit institutions are really masquerading as universities, and they take advantage of students, and before you know it, you’ve accumulated a lot of debt and you have either no degree at all or a degree that isn’t worth very much. Another reason that the cost of college has been going up so rapidly and students have had to borrow so much is that, the states by and large have been disinvestment from public higher education. So the cost of educating students over the last several decades has been transferred in large part from the taxpayer to the student and the student’s family.

Now, it’s a political argument as to whether that’s justified or not, but it is a fact. I haven’t mentioned the private sector, which is what a lot of people think of first when they think of college, famous old institutions in the northeast, like Ivy League institutions and so on. Those institutions, the level of student indebtedness is actually very low, because those institutions are able to provide financial aid for students who need it. So it’s a complicated picture, but it certainly is on the minds of a lot of people, and quite understandably, the cost of college has compelled people to ask hard questions about, “What am I investing in? What kind of return should I be expecting on my investment? What’s the deliverable at the end of this process?” And the answer to that question has changed a lot over our history, and that’s one of the questions I try to explore in this book.

Brett McKay: Well, let’s talk about that, ’cause I think that’s the big question that people ask, “What am I going to college for exactly?” And it’s funny, I took my son to a football camp at the University of Oklahoma a couple of months ago, that’s where I graduated from. And it’s a beautiful campus, but as I was walking around, I was like, “This is really… If you can think about it, it’s kind of weird,” this idea, we cordon young people off from the community, we create a community within a community for a few years where all they can do is focus on learning. Then we build big giant beautiful buildings and libraries, and then there’s football stadiums and all this stuff. And so if you think about it, how did this happen? Where does this idea of college where we take young people for four years of their lives and we just make a small little community. How did that get its start. Let’s start there. I think that’s interesting to explore.

Andrew Delbanco: Well, that’s a great question, and therefore, there’s no real quick easy answer. First thing to say I think is that, the kind of college you’re describing is almost unique to the United States. That is a place where young people roughly between the ages of 18 and 22 let’s say, go, as you say, to be cordoned off from the world to some extent, to live in a community of other young people roughly the same age, and live in the place where they study and grow up. That’s an idea that is quite unfamiliar in most of the world where most people who go on beyond secondary school to university, they live in town, they go and listen to the lectures, they may have a friends group, but there’s nothing like residential campus life in most other countries. So what we take for granted in this country is actually very strange in the eyes of the rest of the world, particularly you mentioned the football stadium, particularly big college sports, which is a completely foreign idea in most countries. But specifically, so where did this uniquely American institution of the residential college, which is what we’re talking about right now, and we don’t wanna forget that most American students do not attend such institutions, we’ll get back to that.

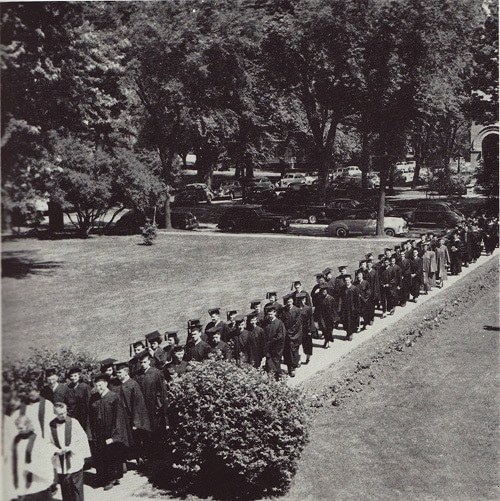

Where did this idea of the residential college come from? And the answer is pretty straightforward, it came from England. It came from the colleges of those ancient universities, Oxford and Cambridge, where a young men, and there were of course only men in those days, came together initially to prepare for careers as ministers in divinity by and large, and spent three, rather than four years, literally behind locked gates so that they were separated from the outside world. And that idea of the residential college got transferred to what became our country in the early 17th century in Cambridge, Massachusetts, when Harvard College was founded, our oldest college.

And in fact, the founders of the college, it’s very interesting to read their admission statement that they published when they opened the college, they said very specifically, “We want students here to grow up in what they called the Collegiate way,” and if you think about that word “collegiate” related to collegial, collegium, community, they wanted students to learn from each other and to live with each other. They wanted to… I guess you could say the boundary line between study and life to be a blurry one. It’s not that you came in to study and then you went back into the world, but you came into a whole world that was about study, gaining in self-knowledge was the hope, developing a character committed to public service, because most of these students were initially trained to be either ministers or school teachers. So they very explicitly designed this college in contrast to the European university where students kind of dropped in to pick up some information and then dropped out again.

Brett McKay: So there was almost a monastic experience they were trying to create.

Andrew Delbanco: Yeah, well, monastic, it’s tempting to go to that analogy. There is something like a convent or a retreat or a monastery, but I can assure you that students never behave monastically. [chuckle] One of the first things you realize when you start reading about the ancient colleges of Oxford and Cambridge and early Harvard and early Yale, is that a lot of the things we think are indicative of a decline in student morals today have always been true, right down to food fights, riots over the quality of the college food, being out after hours when the gates were locked and your friends had to figure out a way to smuggle you back in, putting on wild parties, all of that stuff has always been part and parcel of the college experience.

Brett McKay: Now, I think you noted some experiences in the past, and I’ve read this too, of just outright riots that were happening on the campuses over something, and they would go and attack the President’s house, throw rocks through his window. And the next day the president would get up, he’d give a lecture in front of these hooligans who just pelted his house with rocks.

Andrew Delbanco: Yeah, I think over the long sweep of history, today’s college students are actually relatively better behaved than their predecessors were.

Brett McKay: But back then in colleges, the early colleges, they took that in account, that the fact that young people were still rough around the edges, they were works in progress, so they’re malleable. So when you look at the founding documents of these early colleges, a lot of it was about character building, like they said, “We’re making this college to develop the character of these students while they’re here with us so they can go out and do good in the world.” So that was the purpose, character development. Did the curriculum… Or how did the curriculum of these early colleges reflect that purpose?

Andrew Delbanco: Well, I referred earlier to the mission statement of Harvard College, which came out about 1638. It was not only a mission statement, it was also, you might say, the first fundraising brochure in the history of American higher education. They wrote a document and sent it back to their Puritan allies in England and said, “Hey, we need your help. We need your support to maintain this college.” And in that document, there’s a beautiful line that’s always struck me with great force. They say, “The purpose of this college,” I’m paraphrasing now, “is to ensure that we do not leave an illiterate ministry. We do not leave an illiterate ministry to the people when our present ministers lie in the dust.” So the mission there was very explicit, was to prepare the next generation in the face of the inevitability of death, to prepare the next generation to carry on the Christian ministry to the people of New England. Simple as that.

Now, the mission, of course, grew enormously. And if you asked today, “What’s the mission of that particular institution,” there’d be 150,000 different missions. But in that original mission, I think is that implication that we are here to help people cope with the trials and tribulations of life to understand how to live a virtuous life, how to serve other people, and how to face death when that moment comes. But that’s a pretty tall order. But I think that’s at the heart of what the original mission was all about. But on this subject, it’s one thing when most American colleges belong to one Christian denomination or another. Those early ones were all Protestant. So in fact, the process of Harvard becoming Yale and Yale becoming Princeton, was a sort of a schismatic process, the way churches break up when some part of the congregation isn’t happy with the minister or what’s going on, they’ll go off and form a church of their own. That’s essentially how the early colleges proliferated.

But in that era that lasted throughout the colonial period and into the first half of the 19th century, most colleges were explicitly Christian institutions. And indeed, most college presidents until the late 19th century were clerics, they were ministers. So in that context, people felt relatively confident in how to answer the question of, “What does it mean to develop a good character?” It meant to be a believing Christian who lived according to the precepts of whatever particular brand of Christianity was at home in the particular college. We now obviously live in an era where that criterion no longer applies. Some people might miss it, but there’s no going back whether one wants to or not. We live in an era where there’s a great… I hardly need to point this out to you or your listeners, there is a great deal of debate, dispute, argument, and even animosity and hatred over basic questions such as, “How should people behave in their private sexual lives? Where should the line be drawn between ambition as a good thing and greed as a bad thing? What does a good life look like? What does it mean to commit to a family? What does a family look like?”

There as many answers to those questions now as there are thinking people in our country. And therefore, for any institution to say, “We’re here to train you to be such and such a kind of person,” it’s still possible for institutions to do that, and there are some institutions that define good character rather narrowly, but most of the more visible colleges in our country are trying to accommodate a great diversity of points of view, people from all walks of life, different religious and cultural traditions, different ethnic and racial identities, and to try to help them create some kind of workable community where people can agree at least on the basic elements of what it means to be a citizen, a neighbor, and a productive member of our diverse and heterogeneous society. That’s a tall order. That’s very hard work. For that reason, I think most colleges have more or less given up on it, and I’m sorry about that. I think we should be trying harder to continue to help young people find their way through life with some sense of who they are and who they wanna be.

Brett McKay: Is that probably why now, college today, there’s less of a… I mean they still talk about, “We’re here to develop the whole person, the character. But because there’s no single shared telos, because we’re… They can’t really… It has to be very vague. So as a consequence, universities and colleges today, I think it’s typically why we see it like, “Well, college is a way where you can get a credential so you can go and work.” The economic part is what’s emphasized instead of the character part, ’cause it’s easier. You can say, “Well, you get a degree, you can get a job.”

Andrew Delbanco: Right, right. Well, and look, it’s not only easier in a sense, it’s also completely understandable. One of the great success stories in American History is the way in which we have opened up college to incredibly larger portion of our population than the founders of those institutions would ever have imagined. We’ve made it almost universally available, and that’s a great thing. One of the results of that, of course, is that college is no longer the preserve of affluent people who don’t have to worry about what they’re gonna do after college. It’s a place filled with young people who, as we said earlier, have taken on debt or their families have made financial sacrifices. So most everyone who goes to college legitimately has on their mind the question is, “Okay, I’m gonna get this degree after four years, how am I gonna make that into a marketable credential? What’s it gonna bring me at the end of the process.

And that’s a very legitimate question, particularly for young people who come from families who don’t have a lot of resources, what I regret, and I guess you asked me at the beginning of the conversation, why did I write this book, and I suppose it’s a little bit of a sermon in its own way, what I regret is that even as our colleges work hard to prepare students for productive working lives, you’re gonna be an engineer, or you’re gonna be a healthcare worker, or you’re gonna be a computer programmer, or whatever it may be, we shouldn’t give up on that other aspect of the college experience, we shouldn’t, I think, be telling students, “This is the right way to live, and that’s the wrong way to live.”

But we should be giving students an opportunity to ask those questions, not just privately, silently in their own minds, which all students do, to one extent or another, I believe, but to have conversations about those kinds of questions with their peers, with their contemporaries, and colleges could do a better job of fostering and facilitating those kinds of conversations, some of which can happen outside the classroom and do happen outside the classroom, of course, but some of which could and should happen inside the classroom, and that’s what we used to call… And we still call it that, but it doesn’t have much meaning anymore in most places, we used to call it general education, we made a distinction between the major, the special field, where you got a credential that said you know how to do X or Y, and general education, which was supposed to broaden your horizons, deepen your imagination, open your mind to the experience of other people, not only in the contemporary world, but people in the past.

It’s often said the past is another country, and it’s not a country that anybody can visit except by reading about it, and yet by studying the past, which is a large part of what college used to be about, one gets a sense that the world doesn’t actually have to look exactly the way it does today. It has been different there are some… Some societies have been run by monarchs or tyrants, other societies have tried to make democracy work, other societies have done a mixture of the two, some societies believe in the radical principle of free speech to be protected at all costs. Other societies have strict limits around what individuals are permitted to say in public and penalties applied if they say something that government disapproves of, it’s helpful to know that human beings have organized themselves in different ways over time, and that we collectively have a choice about how we want our society to be in 10, 20, 50, 100 years from now.

Those are the kinds of questions that I think belong in the curriculum of every college, whether it’s a nursing program or an engineering school, or for those very small and dwindling number of students who wanna become professors when they grow up. Everybody should have a chance to think about these kinds of questions. And so I hope that in the years ahead, educators will make a greater effort in that direction and parents will understand that that’s a legitimate and important part of their children’s college experience as well.

Brett McKay: We’re gonna take a quick break for a word from our sponsors.

Brett McKay: And now back to the show. Yeah, I think that’s a big point you see throughout the book is as you look back to the past, you see that at the beginning the curriculum was very interconnected, interdisciplinary, there wasn’t a lot of specialization, the math was connected to the philosophy and the philosophy was connected to the science. So the idea was to give a student a general liberal arts education, so one trend that’s happened… Okay, let’s talk about one trend that’s happened. We mentioned the shift from focusing on character development to the economics, because that’s just… It’s understandable that colleges had to do that, ’cause we’re a diverse heterogeneous society, the other shift has been more from general education to a very specific or specialized instruction.

Andrew Delbanco: Yeah, well, a lot of smart people long before this conversation have pointed out that one of the characteristics of the modern world is the relentless trend toward increasing specialization. Technology, for example, on the one hand, is supposed to make life easier and simpler and more manageable, but creating new technology, even learning how to use new technology is a specialized skill. Science which has become the center of intellectual life in so many ways, where the exciting discoveries are being made and where we can feel its presence in our everyday lives, the scientific knowledge is expanding at an incredibly rapid rate, so there’s no way that even the smartest young person can be an omniscient, all-knowing renaissance man scientist like say, Isaac Newton was or Galileo.

The student has to focus on a particular field, whether it’s biology or physics, or the new growing field of neuroscience, and there are innumerable number of specialized courses that you have to complete on route to a degree in any one of those fields, and that’s just a first degree, that’s the BA degree or the bachelor science degree. So the pressure of specialization is everywhere on all of us all the time, and it has the effect of crowding out space for reflecting on broader questions, of just taking a pause, taking a breath, putting the textbook or the problem set aside and experiencing being alive and asking yourself what you wanna do with this opportunity to be alive.

Those questions are not very evident in the college curriculum anymore, although every once in a while somebody will… Like at Yale, they have a famous course called Happiness, and it was jammed with, I think 1000 students wanted to take it. At Harvard they have a course called Justice, which is very popular with students. So students have an appetite to confront these big questions, even as they know, they have to prepare themselves to take the LSAT exam if they wanna go to law school or the MCAT, if they wanna go to medical school, or whatever the special focus may be. They still crave that opportunity to ask the big humanistic questions, and I think college is ought to be doing a better job of giving them that opportunity.

Brett McKay: And so that’s the value of a liberal arts education, even in the 21st century, allows you to think about what does it mean to be a human and what does it mean to live the good life. And so you mentioned it’s getting harder to teach that stuff because it’s often those general ed courses or liberal arts courses, they’re kinda giving the short shrift, it’s just like, “Well, I just gotta get through this.” That’s how the students perceive it, but then also there’s something going on on the college level, there’s another change that we can talk about. So you mentioned the Early College in the United States, they were very small, cozy, collegial, you wanted to have this intimate relationship with your teacher, where you had these discussions, but throughout the 19th century, things started getting bigger and we shifted from a college to a university system. I think that some people… That’s something to be interesting to explore, I think when we throw around college and university, we use them as synonyms, but they’re not, they’re different. Walk us through the difference there.

Andrew Delbanco: No, I think that’s right. We use those two words interchangeably, Sally is going off to Williams, and Johnny is going off to Wisconsin. In the first case, it’s a college, in the second case is a university, but we make no distinction in our mind, there’s a big distinction, and I would try to boil it down this way. First of all, University is a much more complex institution that does a lot of things, it conducts research, it trains graduate and professional students for the professions, and the college that may exist inside the university tends to be a rather subsidiary entity within this larger thing. But on a more abstract level, what a university is about fundamentally, is the production of new knowledge.

Now, that’s most evident in the sciences, where we understand nature better and better with every passing year, but it’s also true in history where historians discover new aspects of the past and propose new interpretations of the past based on the research that they do in the archives, and so on and so forth. A college has a very different function. A college is about the transmission of knowledge to young people, not in the sense that it’s a static body of knowledge that’s never gonna change, but in the sense that, “Okay. This is what we as a culture have learned about ourselves and have learned about the world. And we want you to know the basics of this so that you can go out and contribute and change the world.” That’s a very different mission from the university mission, and the two tend to get tangled up together and it’s inevitable, I think what you see over the last 125 years or so, is that colleges are becoming more and more like universities.

And there are some positives about that, but by and large, I think more is being lost than is being gained, the pressure on the college student to specialize earlier and earlier, the pressure on the college student to be able to say on the day when they walk through the door, “This is gonna be my major, this is gonna be my career,” that’s the sort of university ethos, whereas the taking the time to sit back and explore and reflect and figure out what makes you excited, and taking the chance of studying something that you might not be very good at, but that you’re curious about it, so you might get a bad grade, that’s gonna bring your GPA down. Those opportunities have become narrower for college students, and they were even when my generation was in college back in the 1970s, a long time ago by now.

So this is a long-standing tension between college and university, and one thing young people can ask themselves when they’re thinking about where they wanna go to college is, do they wanna go to an institution that’s inside a big university, or do they wanna go to a free-standing independent college where that university ethos may be a little lighter, that doesn’t mean they won’t get great science, in fact, there’s a lot of evidence that pre-meds at liberal arts colleges do better than pre-meds at big universities, and of course, the faculty mostly hold PhD degree, so they’ve all been in universities, but there’s still something different about an independent college than a university.

Brett McKay: Yeah, yeah, and I think the point I was going on earlier is that professors, there’s this pressure on professors, that sort of a cross-winds, they’re trying to be a college professor where their job is to transmit knowledge, yet at the same time they have this pressure from the university cross-winds, say, “We need to create new knowledge,” ’cause universities use that in their public relations like, “Hey, we’ve made this new discovery,” or even in the liberal arts or social sciences, and so college professors… I have professors friends where they’ve complained about that, they wanna focus on teaching, but they have this immense pressure to put out a new book or a certain amount of articles, and they feel like they can’t do both very well, so it’s sort of middling.

Andrew Delbanco: Well, this is one of the… It’s a big distortion and it’s a big problem, if you think about it, people who become professors, they get a degree in graduate school and they earn that degree by doing research, very little attention in graduate school is spent on helping you become a better teacher. It’s almost an accident if you have an outstanding researcher who also is an outstanding teacher, it happens, but there’s no logical connection really between the two things, and then when they get to the college or the university, it’s the rare institution that will provide incentives and rewards for people to really throw themselves into their teaching and give the time and attention that undergraduates need, and we could talk for hours more about the trend toward online teaching and learning and what that’s likely to do to the relationship between teachers and students.

But at the end of the day, students need attention, all students need it, especially those who are not as well prepared for college as others, and if we’re gonna ever do anything about our low graduation rates in this country, our poor success rates and the evidence of relatively limited learning that goes on in our colleges, by and large, we have to strengthen this relationship between teachers and students, and that’s a very tall order, which is easy for me as a sort of outside commentator to call for it, it’s a harder thing for a college president or dean or a provost to make it happen, but it’s certainly worth the effort. If I could say one of the things, Brett, to maybe, at least in my own mind, pulled together some of the things we’ve been talking about, we all know that we’re in the middle of this and we’re still in it, unfortunately, this COVID-19 crisis, and it’s very obvious that it is in the first instance, a public health crisis.

And it has also been an economic crisis, especially for less fortunate Americans who work as restaurant workers or retail workers or in meat packing factories, where COVID really took a high toll or places had to shut down, so it’s all those things, is a public health crisis, or economic crisis, but it’s also a values crisis, because it has forced us to ask fundamental questions about individual liberty on the one hand, and government authority on the other. All the debate and dispute we’re witnessing right now over whether or not there should be a mask mandate, whether or not you should get the vaccine, to what extent is getting the vaccine something you should do for yourself, and to what extent is it something you should do in order to protect others around you, not just your loved ones, but also strangers whom you come into contact with. These are not scientific questions, these are not technical questions, these are humanistic values questions.

I don’t have answers to these questions, and it’s discouraging to me that we have so many public figures who are so shrill and certain that they have the right answers to these questions. My point is that we want the graduates of our colleges to be thoughtful, reflective people who are capable of thinking about these questions and not just having opinions about them based on what their parents told them, or what they heard on this or that talk show or TV network, but based on evidence, argument, as opposed to just opinionating and being willing to listen to people with a different point of view on these questions. All human questions are hard questions, and college is a place where students should begin to understand that and understand that they’re gonna spend the rest of their lives thinking about these questions whether they want to or not, so I just wanted to put our conversation in that context.

I hope that makes some sense. There’ll be another crisis in five years or 10 years, we don’t know what it’ll look like, but I can assure you that once again, will not be a problem that’s susceptible only to technical solutions, all human problems are values problems, and that’s why we wanna make sure that the humanities and general education, as I’ve been talking about it, continue to be a part of the college experience, and that colleges don’t just become training institutions to prepare people to perform certain kinds of functions. So sorry if that sounded like a sermon, but I feel pretty strongly about it.

Brett McKay: No, you’re making the strong case for why liberal arts education is still relevant today, even our technocratic society, even we have the technology underlying that is always… We always had to deal with the humanistic questions that go along with it, they’ll never go away.

Andrew Delbanco: Look at the questions that technology has raised, like privacy questions. Every time I turn on my computer, Amazon or Google, they know all about what I was shopping for yesterday and what my interests are and so on, and the free speech questions, can you post lies and slander on Facebook, and there are no penalties for that. Again, these are hard questions, but they’re gonna get the better of us, they’re gonna overcome us, if we don’t have a population that’s capable of thinking about them and debating them and discussing them in a civil way, and I don’t mean this as an idle comment, but in the way that you promote in your podcast, people talking about complicated issues, not yelling and screaming at each other and trying to sell something, but actually trying to think together, and that’s what a college should be about at the end of the day, so that’s my hope for what the colleges will look like in the future.

Brett McKay: So here’s the question, I think you had alluded to earlier. Say, if you’re a young person listening the podcast, or you’re a parent of a young person, and they’re looking at which college to attend and you’re looking for one that will provide that robust liberal arts education, and where you see a good model of that collegial education where there’s an interaction between students and then teachers intimate, and it’s edifying. What advice would you give to those people to find that right college?

Andrew Delbanco: Well, I would say I’d say a couple of quick things. First of all, it helps to understand that most American students don’t have the luxury of making that choice. So what we’ve been talking about for the whole time together here, which is fine, is a certain stratum of the undergraduate experience, the college that you get in the family car or maybe in your own car, or maybe you take an airplane or a train and you go there, and you move in and you live there for several years, that is not the typical experience for most American students who attend underfunded, over-crowded public two-year or four-year institutions often as commuters. So that’s one thing that young people should realize if they’re in that position, is a fortunate position to be in.

The second thing I would say, and I find myself saying this a lot when parents come to me, ’cause I wrote this book about college, so I’m supposed to know something about it. The only thing that really matters is that whichever college you go to is one that you feel good about. It doesn’t matter where it is on the prestige ladder, it doesn’t matter how many faculty have won the Nobel Prize or have a high rating in the citation index, it doesn’t matter if the football team is good or bad, at least not in my view, it only matters that you go there with a feeling of excitement and curiosity and desire to learn, and there are hundreds, if not thousands of institutions in our country that can be that place for you.

So one of the really sad things has been to see how the prestige mongering of the last quarter century and more has distorted the lives of young people who, not just in high school, but in middle school and even in practically, in pre-school, are under pressure to perform well on standardized tests and get that extracurricular summer experience that they can put on their resume and so on and so forth, all of that is distorting the lives of young people, and none of it has anything to do with what we’ve been talking about, learning and growing. So finally, what’s the right college? It’s the college that feels right. And that’s gonna be an individual choice. In general, it’s a good idea to go somewhere where the faculty actually care about the students. And the degree to which faculty care about students might actually be an inverse proportion, in some cases, to the prestige of the institution, because if you are going into a place where the faculty spend most of their time doing research or traveling around the world telling other people about their research, they don’t have a lot of time for students.

So you gotta feel it out. You gotta… And the process of choosing a college, if you are one of those privileged relatively few who can choose, the process itself should be a learning experience, should be an educational experience because it should require you to ask questions about yourself, “What do I get excited about? What kind of people do I wanna be around? Do I have… Is my comfort zone large enough that I can go to a place where there are gonna be a lot of students who are not like me, don’t look like me and who come from other parts of the country or the world? Or do I really need to be in a place where I feel comfortable and people have had a relatively similar experience to my own?” There’s no right or wrong answer to those questions either. But those are the kinds of questions that you should be asking. Not where does this institution stand in US News and World Report, which is a whole other subject.

Brett McKay: Right. And I think another takeaway too, this is from my experience is that no matter where you go, you can create that collegial experience wherever you’re at. It doesn’t matter if you’re at Harvard or the University of Oklahoma. So my best memories from my college days at Oklahoma. Yeah, I went to the football games. That was fun, but I loved meeting with a bunch of students after class and continuing the discussion that we had about Aristotle’s Politics. That was great, I loved it and I miss it, and I’m glad I had those experiences.

Andrew Delbanco: Well, that’s the way it should be. And I’m not surprised to hear you say that because otherwise, you wouldn’t be doing what you’re doing, but the best teacher I ever had, whom I think about every day when I teach myself, used to say that the best kind of class is not one that ends with a conclusion, or the answer to a question. The best kind of class is one where the students leave the room wanting to talk more and wanting to think more about what’s just been under discussion, and if you can find a college where that’s happening, then you’re in good shape and take advantage of that and you’ll get a lot of value out of your investment in college, and I wish to all your listeners that that will be the case for them.

Brett McKay: Andrew, where can people go to learn more about your work?

Andrew Delbanco: Well, my work is a little bit all over the place. My last book is actually a history book about how enslaved persons who ran for freedom in the years before the Civil War changed the course of American history, and how it would be good for all of us to know something more about their history than we tend to do. So I’d be delighted if your listeners wanna go read this little book about college, which is a bit out of date by now, but if they wanna read my most recent book, The War Before The War, which I subtitled “Fugitive Slaves and the Struggle for America’s Soul, From the Revolution to the Civil War,” that would be nice too, and I think they’ll find that it’s possible to actually read it.

Brett McKay: Well, Andrew Delbanco, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Andrew Delbanco: Thank you so much. I hope we’ll get a chance to talk again and you have a great day.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Andrew Delbanco, he’s the author of the book, College: What It Was, Is, and Should Be, it’s available on Amazon.com and book stores everywhere. For more information about this book and his work and dig deeper into this topic, go to our show notes at aom.is/college.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM podcast. Make sure to go to artofmanliness.com, where you can check our podcast archives, where there’s thousands of articles that we have written over the years about pretty much anything you think of. And if you would like to enjoy ad free episodes of the AOM podcast, you can do so on Stitcher Premium. Head over to stitcherpremium.com, sign up, use code MANLINESS at checkout for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the Stitcher app at Android or iOS and you start enjoying ad free episodes of the AOM podcast. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on Apple podcast or Stitcher. It helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you, please consider sharing the show with a friend or a family member who you think will get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay reminding you to not only listen to AOM podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.