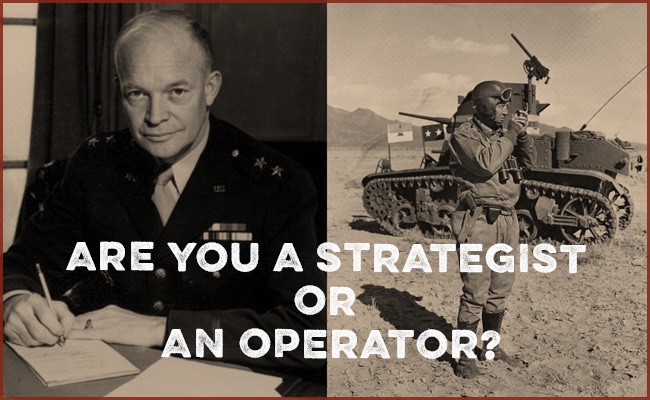

In the years after World War I, longtime Army colleagues and friends George S. Patton and Dwight D. Eisenhower contemplated what would happen if another global conflict broke out. As Patton envisioned it: “In the next war, I’ll be the Stonewall Jackson, and you can be the Robert E. Lee. Ike, you do the big planning, and you let me go in and shoot up the enemy.”

And that’s pretty much how things worked out in World War II.

Eisenhower led from Allied headquarters as Europe’s Supreme Commander, while Patton served on the ground as commander of the Third and Seventh armies.

Ike, who lacked battlefield experience, was nonetheless brilliant as a theater commander. Having spent his career as a highly effective staff officer, he had a genius for planning, marshaling material, organizing logistics, and practicing diplomacy. Charming, modest, flexible, and steady, he excelled at getting the disparate and sometimes rivalrous Allied leaders to work together, interfacing with politicians and the press, and keeping all the pieces of a monumental war effort sorted and spinning.

Patton, on the other hand, had little patience for politicking and wasn’t lauded for his ability to formulate high-level plans. But, he possessed all the traits necessary for superior battlefield command. Bold and aggressive, he executed missions with mastery and confidence and advanced with relentless drive.

While each man’s position and responsibilities were different, each excelled in his particular role.

Ike was the consummate strategist.

Patton was born to be an operator.

Strategists Versus Operators

Andrew Wilson, a professor at the Naval War College, describes the difference between Eisenhower and Patton as the difference between having a bent toward strategy versus having a bent toward operations.

Wilson defines strategy as “the means by which you translate political purpose” — what the political leadership hopes to achieve with a war — “into military action, and how it is that you anticipate military action to deliver your political purpose. . . . So strategy is the bridge between policy and military actions.”

Operations, he says, are those military actions — “essentially the big muscle movements, the battles.”

Those who excel in that second kind of work — operators — do best on the ground and in the field. They excel at, and derive satisfaction from, practicing and carrying out a certain skill, craft, or art.

Those who excel at the first kind of work — strategists — do best in high-level positions. They excel at, and derive satisfaction from, overseeing, organizing, and supervising those who practice and carry out skills, crafts, and arts.

Another way to describe the strategists versus operators dichotomy is as managers versus tacticians.

It’s a distinction in men’s proclivities that extends beyond the military context, and it’s crucial to know which category you fall into.

Are You a Strategist or an Operator?

While there are a few men who are adept at both strategy and operations, most primarily lean toward one over the other.

Problems arise when men don’t have the self-awareness and foresight to understand their personal strengths and propensities, and end up in a role for which they are ill-suited.

Strategists Becoming Operators

Sometimes a man is doing well as a manager type, but may desire a job in the field, perhaps because such work seems “sexier.” For example, he may have done well for years as a supervisor within a company, but thinks about striking out on his own and becoming an entrepreneur, even though the skill set necessary for success in the former pursuit isn’t likely to translate to success in the latter.

Eisenhower thought about making this kind of shift.

In the lead-up to WWII, Ike thought he’d like to work alongside Patton and become the commander of an armored regiment. He had never seen combat; because he was so good at training others, he had been kept stateside during WWI and tasked with preparing troops to deploy. Having missed out on the consummate experience of a military career during the First World War, he was determined to get into the field during the Second.

So when in 1941, a general in the War Plans Division asked Eisenhower to consider joining its staff in Washington, Ike demurred. He really liked the prospect of that position, and knew he’d do well there, but felt that a field command was something he was supposed to prefer. He felt conflicted, and worried he’d “pass[ed] up something I wanted to do, in favor of something I thought I ought to do.”

Eisenhower needn’t have worried. While he continued to position himself for field command, his administrative abilities were too valuable to be dispensed with, and he was eventually appointed chief of staff to the commander of the Third Army, then Chief of the War Plans Division, and eventually Supreme Allied Commander. Ike’s sense of personal satisfaction, and the fate of world history, benefitted from his sticking to these strategic positions.

Operators Becoming Strategists

What happens more often than managerial men trying to shift into tactical roles is tacticians being promoted into administrative positions. Those who excel in operational roles are frequently moved up the ranks. The problem is, the skills required to succeed as tactical operators don’t typically translate into success as strategic supervisors. This is the essence of the “Peter principle.” And not only may a tactician placed in a managerial or executive job struggle to be competent in that position, he is also unlikely to enjoy it.

Entrepreneurs who successfully launch start-ups often don’t transition well to becoming the CEOs who run them. Fitness coaches who excel at training clients frequently flounder at owning their own gyms. Pastors who have the skill set to plant churches don’t always have the skill set to oversee the large, established congregations they grow into. Doctors who like practicing hands-on medicine won’t be satisfied spending their days supervising teams of nurses. Academics who enjoy teaching end up less happy as deans than they were as professors.

Writers and artists, who initially function as fully autonomous operators, sometimes try hiring assistants and social media gurus to expand the empire around their “brand,” but find they’d rather keep their “business” smaller than to give over any of the time they could be creating to managing other people.

Sometimes an operator has to transition to being a strategist because the fieldwork they do is physical in nature and takes a toll on the body. As a man who works in the trades gets older, for example, he may find it desirable and/or necessary to move from working on projects himself to supervising the work of others.

But oftentimes, an operator ends up in a managerial position because he feels he’s supposed to take it and defaults to following the standard professional trajectory. The next rung up the ladder may take someone out of the field, but the position comes with more money, power, and/or status. A man thinks he ought to keep moving up in the world, even if that “advancement” puts him into a position he’s less suited for and finds less fulfilling.

Do You Want to Be in the War Room or in the Trenches?

It’s important to know who you are: a strategist or an operator.

If you’re a manager type, lean into that, even if that job may not seem as sexy as others. Administrators are absolutely crucial in keeping the world spinning round, and even help win world wars.

If you’re the tactician type, do some real reflection before you accept that “promotion.” Is the benefit in money and status worth the tradeoff in fulfillment that comes from doing a job you’re brilliant at and love? It’s okay to recognize that you like carrying out orders more than formulating them. And it’s okay to value the chance to practice the things you’re really skilled at more than a bigger office.

When Eisenhower was serving as Allied Supreme Commander in North Africa during WWII, his forces experienced some initial setbacks on the battlefield, and the Army’s Chief of Staff, George Marshall, suggested that Ike bring Patton in to serve as his deputy and oversee the fighting. But Patton balked at the idea of taking a more administrative job. He understood that he could do more good on the ground than at HQ, and that an operator belongs in the field — not behind a desk.