Editor’s note: In 1944, the US War Department published FM 21-22, a manual on military watermanship. The manual covers everything a man needs to know to survive at sea, from how to properly abandon a sinking ship to how to stay alive in a lifeboat. This week we’ll be highlighting several of the manual’s sections; the information is both fascinating from a historical standpoint and useful for worst case scenarios.

FM 21-22 War Department Watermanship Manual, 1944

Abandoning Ship

LEAVING THE SHIP.

a. When the lifeboat is being lowered into the water all occupants who are not aiding the crew should remain low in the boat and out of the way. All men must be quiet and take orders only from the man in charge. The lower ends of all ladders, nets, or ropes down the ship’s side should be pulled out and away from the ship to aid men descending into the boat. The lifeboat must be kept away from the ship’s side to prevent its being crushed or capsized. The lifeboat should be moved rapidly at least 50 yards from the ship to escape the suction of the sinking ship. Once out of the danger area, the sea anchor should be dropped and all men should remain low in the boat until the confusion is over. The mast and sails are rigged only when the men have quieted down, because in their excitement they may fall overboard. Without endangering the entire boatload as many survivors as possible should be picked up from the water. Men may hang on to the life line around the lifeboat. If there is room, men on rafts should shift over into the lifeboat. All boats and rafts should stay together to increase the chances of rescue and bolster morale.

b. Before the signal to abandon ship is sounded, all persons are given the following information: the ship’s approximate location, the direction and distance to the nearest land, and the result of SOS signals. If a rescue ship has answered the SOS, lifeboats remain near the spot where the ship sank. Otherwise, the location of the ship and the distance and direction to land can be used to steer a course.

Right capsized lifeboat by pulling down on girth lines.

c. If the lifeboat capsizes, five or six men can right it by reaching over from one side and pulling down on the keel or girth lines — ropes running across the bottom of the boat.

BOARDING LIFEBOATS AND RUBBER BOATS.

a. Lifeboats.

(1) Because of their high sides and general shape lifeboats should be boarded from the center of one side. Face the boat squarely, hook the arms over the side, wait for the next swell to raise your body, and with a kick roll into the boat.

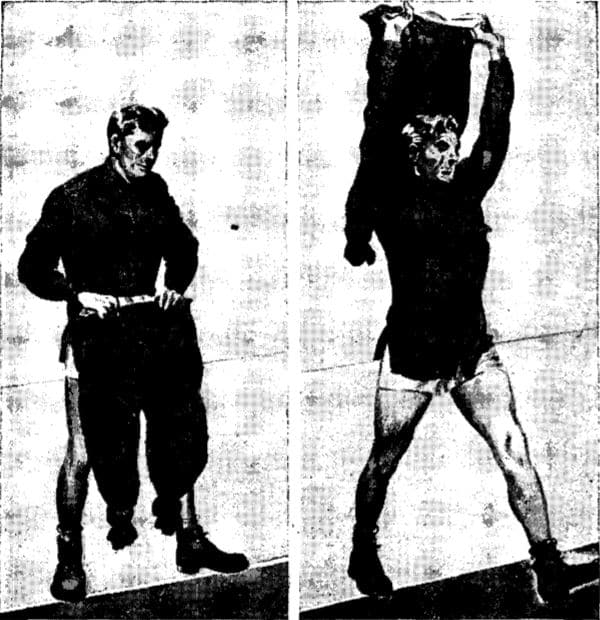

Help survivor into boat by lifting him until body can be bent at waist; grasp leg and pivot rest of body into boat.

(2) A man in the lifeboat should aid the survivor by lifting him above the edge of the boat until his body can be bent at the waist. This brings the head and shoulders into the boat. The rescuer then grasps a leg and pivots the rest of the body into the boat.

Board rubber boat over the side when there are two or more survivors. One man clings to side of boat. The other, on opposite side, places one arm in boat and locks it against side. He then grasps top of side with other hand, lifts leg over side and hooks foot inside boat. As next swell lifts boat, he pulls with arm and leg in boat, kicks down with foot in water, and rolls into boat.

b. Rubber boats. A lone survivor should board a rubber boat over the bow or stern. With more than one man, entrance over the side is recommended. One man clings to the side of the boat. The other, on the opposite side, places one arm in the boat and locks it against the side. He then grasps the top of the side with his other hand, lifts his leg on the same side as the arm in the boat and hooks the foot inside the boat. As the next swell lifts the boat, he pulls with the arm and leg in the boat, kicks down with the foot in the water, and rolls into the boat. The other survivor then boards the same way.

ENEMY STRAFING.

Enemy aircraft may strafe the boat. Because of its high speed, the airplane’s attack will be brief. Bullets from low-flying airplanes either ricochet off the water or penetrate no more than 24 inches below the surface. Hence, all who are physically able should go overboard prior to attack and bob under the water 24 inches. If sails are set, lower them or boat will sail away by herself. Another defense is to swim away from boat at right angles to airplane’s line of flight. All men who cannot get into the water should drop to the bottom of the boat. If all men go overboard, the strongest swimmers should grasp ropes from the boat to keep it from drifting away with the current or wind. Immediately after the attack plug up all bullet holes with the wooden plugs and cloth.

ABANDON-SHIP PROCEDURE; OVER THE SIDE.

Observe the following precautions when ordered to abandon ship over the side:

a. Enter the water with the idea of reaching a boat, raft, or other object which will support you. If possible, choose your objective first.

b. Avoid entering the water:

(1) Where there is oil or flame.

(2) Between the ship and a boat or raft close to it, which might crush you against the side.

(3) Near the propellers, if the ship is under way.

(4). Amidships, as your vessel may have a bilge keel at that point which cannot be seen under water but may cause serious injury if struck by you when falling.

c. Enter the water:

(1) From the part of the ship nearest the water, fore or aft if possible.

(2) On the windward side. An exception to this may arise when ship has been struck on the windward side and is losing oil or gasoline on that side. Under these circumstances, enter water on opposite side and immediately row or swim away from ship, beyond her stern if possible.

(3) At a spot free of debris.

(4) Where barnacles are fewest.

JUMPING WITHOUT OIL.

a. Precautions; jumping with life jacket.

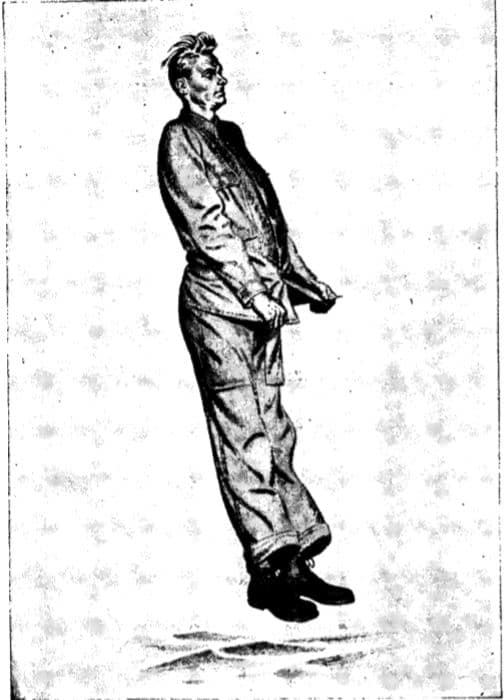

Jumping with life preserver from high freeboard. Hold life preserver in one hand. Secure it to your belt with a short line.

When all other means of leaving the ship are being used to capacity or are out of order, jump, don’t dive, and look before you jump. Observe the following precautions in addition to those outlined in the section on “Jumping”:

(1) Take a deep breath before jumping.

(2) With the downward roll of the ship, step forward as though taking the next stride, and, springing from the other foot, bring the legs together in the air. Drop vertically into the water. When lower side of listing vessel also is windward side, take care to avoid being washed back against vessel.

(3) Do not look down. Keep your head up.

(4) Jump as far from the ship as you can.

(5) Do not try to break your fall with the hands or arms.

(6) Keep legs together. After entering the water open them to check depth of plunge.

(7) Use of arms.

(a) Without life preserver. Hold the nose and protect the face.

(b) With life preserver.

1. Jump, holding the jacket in one hand; if it is jerked from your hand when you hit the water, recover it when you come to the surface. (Pictured above, left.)

2. Secure jacket to your belt with a short length of line; enter water. Recover it when you come to the surface. (Pictured above, right.)

3. Secure jacket tightly to body by straps; with arms on top of it, press down hard with forearms, one hand holding the nose; exert plenty of muscular force to hold down jacket and prevent its striking your chin when you hit the water.

b. Shirt as support.

Jumping to use shirt as support in water. Button shirt before jumping; draw shirt front out of trousers and hold it down and forward to scoop up the air.

To use shirt as support in the water, button it completely before jumping. Draw the front out of the trousers, and hold it down and forward with arms fully extended, 6 to 10 inches from the body. This causes the shirt to fill with air, and it will aid in bringing your body rapidly to the surface. By assuming the breast-stroke position on the water, an air pocket is formed in the back of the shirt. This provides some support for a short time.

c. Trousers as support.

Jumping to use trousers as support in water. Tie knot at end of each trouser leg; button fly, flip trousers over head.

Remove and wet or dampen your trousers. Tie a knot at or near the end of each leg. Button the fly. Grasp the trousers by the waist, legs down, and hold in front of your body. Flip the trousers over and behind the head, arms extended, wrists flexed so that the backs of the hands are down.

As feet hit water wrists flip forward bringing knuckles up as body enters water.

Jump, and, as the feet hit the water, snap the hands forward from the wrists to get the waist of the trousers under water. The air which is trapped in the legs helps return you quickly to the surface.

Take prone position and place one leg of trousers under each arm pit.

For surface support, take a prone position and place a leg of the trousers on either side of your body, below the arm pits.

Jumping to use barracks bag as support in water. Wet or dampen bag and jump as with trousers. Hold bag to prevent its overturning.

d. Barracks bag or pillow case. Wet or dampen the bag and proceed as with trousers. After entering the water, hold the bag with both arms to prevent overturning. If sufficient air has not been trapped, take a big breath, submerge, exhale into the mouth of the bag, and rise to the surface.

e. When jumping with sheet, poncho, squares of canvas. Gather or knot the four corners to form a bag. Proceed as outlined above.

JUMPING INTO OIL OR FLAME.

a. General. Ships normally carry their fuel oil in tanks around the sides which may be burst by bombs or torpedoes, releasing the oil over the water. Oils are classified as thin oils and thick oils. Fuel oil for ships is heavy oil, but thin oil may be on board and be spread by the explosion. Thick oils generally are not inflammable, but are extremely difficult to move through, whether swimming or in a boat. Never jump into or try to swim through thick oil. Distance from the ship to which oil or flames spread depends upon the following:

(1) Speed of ship. If the ship is making headway the oil will stream off to the rear. If the ship is still, the oil may surround the ship.

(2) Wind. The wind may blow the oil or flame away from or back to the ship.

(3) Part of ship hit.

(4) State of sea. Whether smooth or rough.

(5) Temperature of water. In cold water the oil may congeal and remain in one area.

(6) Amount of oil on the water. As the oil layer spreads it gets thinner until it can no longer spread.

b. Precautions. When necessary to jump from a ship and there is surface oil or flame, observe the following precautions.

(1) Remove your life preserver and anything else which might carry you to the surface into oil or flame. Take off your shoes, but keep shirt, trousers, and socks. The carbon-dioxide life belt may be retained if it has not been inflated.

(2) To prevent trapping air under your clothing, fasten all buttons on shirt and trousers, and tuck trouser legs into the socks.

(3) If necessary to jump into oil or flame, jump to windward and swim to windward. The wind will tend to blow the oil or flame away from you, instead of driving them with you.

(4) Close your eyes and mouth before entering the water.

SWIMMING AWAY FROM THE SHIP.

Removing shoes in water. First take up the jellyfish float; draw one leg up and with both hands untie shoe lace; loosen lace and remove shoe.

a. Once in the water, immediately move away from the ship, using the elementary back stroke to protect against injury from explosions from the ship, torpedoes, or bombs. If there are no lifeboats or rafts to swim to, move at least 50 yards from the ship to escape the suction of the sinking ship. When you are beyond this danger zone, remember that buoyancy is the main thing; the distance you swim is relatively unimportant unless land is in sight. Use any debris or wreckage as support. Lash yourself to it if possible. Retain clothing and shoes as protection from the weather, salt, and oil.

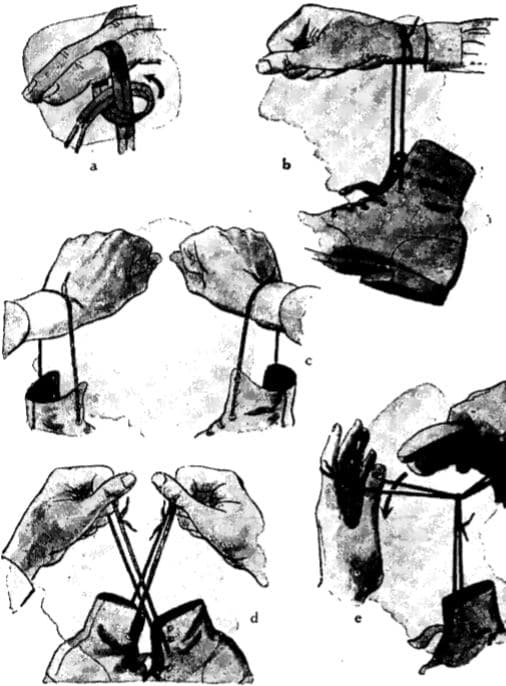

Removing shoes in water. a. Wind both ends of shoe lace once around index finger and draw ends through loop, forming a knot. b. If lace is short, slip hand through loop so shoe will hang from waist; this leaves hand free. With long lace, bend loop over itself to form a slip noose for wrist. c. Remove other shoe in the same way. d. Tread water and pass one shoe-lace loop through other. e. Pass either shoe through its own loop thus securing laces of both shoes. Hang shoes around neck and continue swimming.

b. It may be necessary to undress in the water either to remove the weight of clothing and equipment or to inflate the clothing as support. To undress, take a deep breath, assume the jellyfish float with the arms hanging relaxed, and proceed in a natural manner to remove equipment or clothing. When a fresh breath is needed a stroke or two, as in a modified breast stroke, will bring your mouth above the surface. Make all movements slow and deliberate. Do not discard any clothing unless forced to, as it may be useful later. Shoes can be tied together and hung around your neck.

SWIMMING THROUGH UNIGNITED OIL.

After entering the water, open your eyes and swim away from the ship. While under water, look for thin spots or breaks in the oil, indicated by lighter areas. If your breath becomes short before you have found a break, come to the surface with hands and arms preceding the head, and eyes closed. Scatter the oil by a pushing and sweeping arm motion as in a modified breast stroke. Kick your feet hard, to rise as far as possible above water before breathing. Open eyes and try to locate the nearest clear spot before again submerging. While above the surface, keep sweeping the oil aside. Close your eyes before submerging.

SWIMMING THROUGH FIRE.

Jump feet first to windward of ship or airplane. As you jump, cover your eyes, nose, and mouth with both hands. Take a deep breath. Hold breath until you rise to the surface.

a. Jump feet first to windward of ship or airplane. If jumping with life vest from a moderate height, as from an airplane, cover eyes, nose, and mouth with both hands. Take a deep breath; hold breath until you rise to the surface.

b. Before reaching the surface look for thin spots or breaks in the fire where a breath may be obtained. These spots can be recognized by their relative dullness; bright spots mean hot, strong fire. If a break is found, rise into it; if no break is found, rise into the thinnest spot available.

Just before you pop to surface, make a breathing hole in flames by swinging arms overhead, splashing flames away from head, face, and arms.

c. Just before breaking through the surface, cross your arms on forehead, palms up, and push upward with a strong kick. When breaking the surface, swing your arms overhead to splash flames away from head, face, and arms.

Swim into the wind. Use breast stroke. Splash water ahead and to side before taking each stroke. Keep your head cool by ducking underwater every third or fourth stroke.

d. Swim into the wind. Use the breast stroke. Before taking each stroke splash water ahead and to the sides. Keep mouth and nose close to the water. Duck your head every third or fourth stroke to keep it cool. If there are several men, swim single file. Let the strongest swimmer splash a path so the rest can follow safely in his wake.

SWIMMING UNDERWATER THROUGH FIRE.

Swimming underwater through fire. Splash flames away from body; hold head near water level; if wearing life vest, deflate it by releasing valves. Take a deep breath but do not inhale fumes; sink beneath surface, feet first. Swim upwind as far as possible. Splash away flames in coming to surface; take deep breath and resubmerge. Repeat procedure until beyond fire.

If the heat is too intense or flames too high, swim under water. To do this:

a. Splash flames away from body.

b. Hold head near water level.

c. If wearing life vest, deflate it by releasing valves.

d. Take a deep breath but do not inhale fumes.

e. Sink beneath the surface, feet first.

f. Swim upwind as far as possible.

g. Splash away the flames as you come to the surface. Take a deep breath and submerge again. Repeat procedure until you are beyond the fire.

h. If wearing life vest, reinflate it by mouth. If you cannot continue to swim under water, as a last resort come to the surface as described above, and use the breast stroke.

EMERGENCY FLOTATION IN WATER.

When in the water without a life preserver improvise expedients.

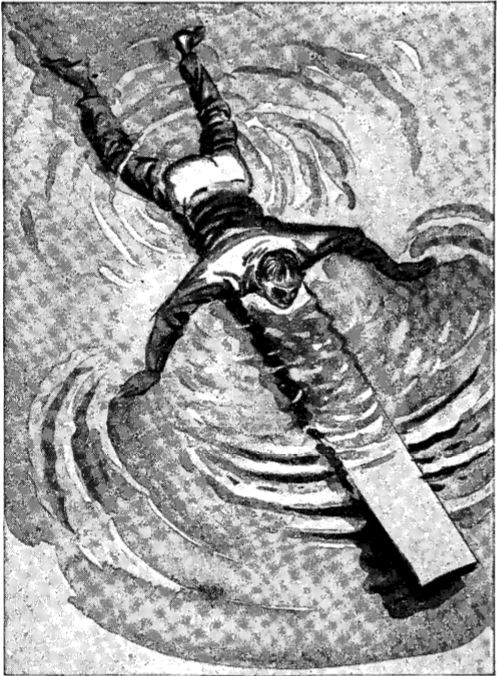

Lie on plank for flotation; use arms and legs for propulsion.

a. Use debris. Any floating debris and wreckage should be used, shared with the greatest number of men. It is better to cling to planks, boxes, and other floating articles than to climb upon them. Clinging to floating debris adds its buoyancy to that of your body. Lash yourself to debris if possible. Trying to climb up on an object often leads to frustration and rapid exhaustion. Only objects large enough for full support should be boarded. Resting the hands or elbows on an object or throwing the arms around it may provide sufficient support. A plank can be used as a surfboard by lying on it, spreading the legs for balance, and using the arms and legs for propulsion.

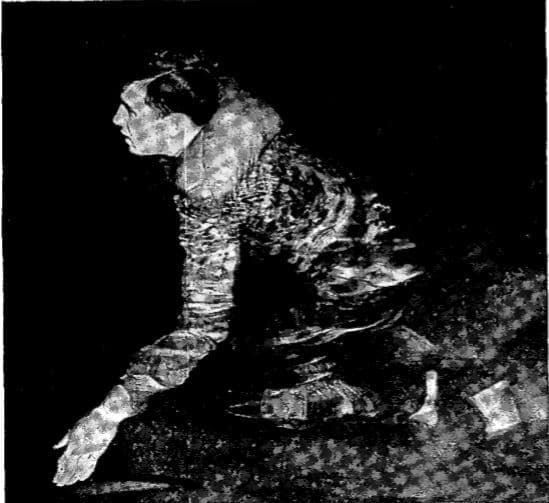

Use shirt for flotation. Fasten all buttons. Take deep breath and assume jellyfish float. Expel air into shirt between second and third buttons. Repeat procedure if necessary.

b. Use shirt. Fasten all shirt buttons, including those of collar and cuffs. Take a deep breath and assume the jelly-fish float. With the fingers, form an opening in the shirt front between the second and third buttons, bring the lips to the opening, and expel the air into the shirt. This action may be repeated. When the prone position is resumed, an air pocket forms at the back of the shirt.

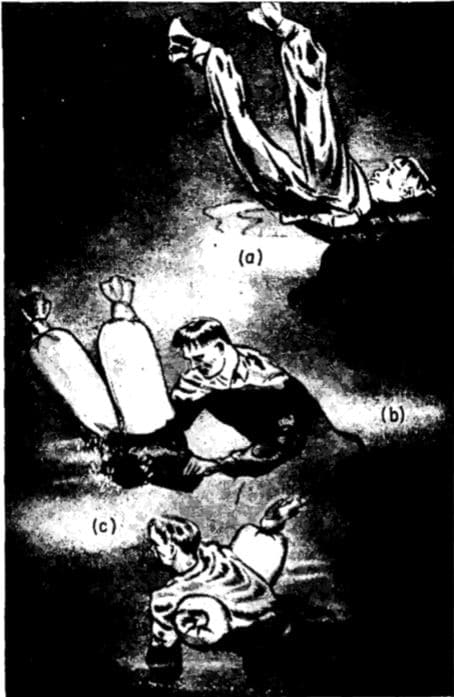

Use trousers for flotation. (a) Remove trousers, tie knot at end of each trouser leg, and button fly. Insert one arm in each leg while treading water. (b) Drop arms quickly pulling waist band under surface. If more air required, take deep breath and expel it into trousers. (c) Place one trouser leg on each side of body under arm pits.

c. Use trousers. Remove the trousers, tie a knot at or near the end of each leg, and button the fly. While treading water, hold the trousers above water by inserting one arm in each leg. This allows air to fill each leg. Drop the arms quickly, pulling the waist band under the surface. This traps air in each leg. The support can then be used in the prone position by placing one trouser leg on each side of the body under the arm pits. If enough air has not been trapped in the legs, take a deep breath, submerge holding the waist band below the surface, and expel the air into the trousers.

Read the Entire Series

Survival Swimming

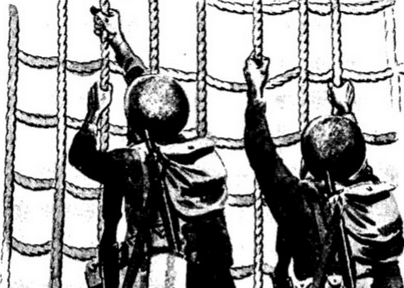

How to Climb Down a Ship’s Ropes and Cargo Nets

Surviving Aboard a Life Raft