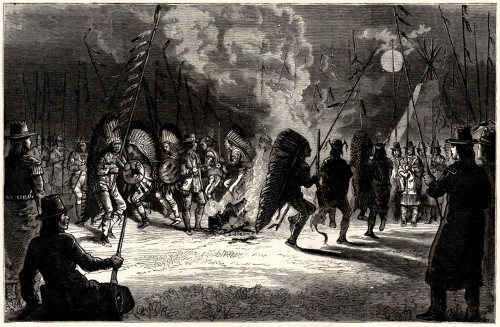

We’ve talked in the past about the importance of young men having a rite of passage or initiation into manhood. Throughout time and across cultures, societies have developed rituals to help usher young men from adolescence to maturity — from dependence to independence.

As has been noted by cultural anthropologists, rites of passage in the West have declined due to many factors, including suspicion of rituals and disintegration of communities. The resulting lack of transitions and pivot points may be a significant source of the ills plaguing men today. Without an initiatic experience into positive, grounded manhood, young men are left to be buffeted by the winds of anomie and nihilism. Instead of stepping into their roles and responsibilities, and gaining a sense of confidence, competence, and purpose, they feel stuck in limbo. Instead of being generative, their masculine energy becomes destructive.

Given the dearth of culturally-embedded rites of passage in the modern world, some fathers decide to create their own “DIY” coming-of-age challenges for their sons. But while this idea is very well-intentioned, fathers are in fact the wrong person for the job.

Why Fathers Shouldn’t Be the Ones Who Initiate Their Sons into Manhood

When we think about classic rites of passage, we often think of fathers initiating their sons into the mysteries of manhood.

But as Richard Rohr — a Franciscan friar who writes about male spirituality and leads rites of passage for men — notes in his book From Wild Man to Wise Man, in both mythology and in traditional cultures, it is rarely the father who directly guides the initiate. Instead, it’s an older male relative or friend of the father (or group of such relatives and friends) who takes the lead in coming-of-age rituals.

Jesus went to John the Baptist, an older male relative, for initiation into his ministry.

The poet Robert Bly notes that in the story of Iron John, it was the wild man, Iron John, that guided the young prince’s initiation into manhood, and not the prince’s father.

In the Odyssey, it wasn’t Odysseus who initiated his son Telemachus into manhood; Odysseus’ friend Mentor took on this task (it’s from this story that we get our English word “mentor”). Of course, Odysseus wasn’t available for the job, but the legend is also trading on an archetypal pattern that transcends the particular details of the poem.

You see this dynamic in modern stories too. English teacher John Keating and his students in Dead Poets Society; Obi-Wan Kenobi (and Yoda) and Luke Skywalker in Star Wars; Coach Eric Taylor and his players in Friday Night Lights; Mr. Miyagi and Daniel-san; great-uncles Hub and Garth and their nephew Walter in Secondhand Lions . . . in our cinematic tales, a boy gets mentored by someone other than his father, whether or not his father is around.

So too, in traditional real-life cultures all around the world, it was typically a boy’s uncles and relatives who taught him the secrets of manhood during his rite of passage.

Rohr argues that the relationship between a biological father and his son is too complex for the former to be the latter’s initiator. When a dad leads his son’s initiatic experience, his own identity and sense of self are on the line. This could result in a dad going too easy on his son or being overly harsh to ensure he passes the test. A father has too much invested to lead an initiation impartially.

And we have to remember that one part of an initiation into manhood is separation. A boy is trying to become less dependent and more independent. A father is likely wrapped up in his son’s sense of boyish self; he sees his son through the filter of having watched him grow from a baby. Becoming a man requires a boy to separate himself from that image and dynamic, and that requires separating himself from his father. But if Dad is the one leading the rite of passage, that process of separation could be stunted.

Further, a son is so familiar with his father, that he may be less likely to listen to him and more comfortable pushing back against his counsel and challenges. Young people are more apt to take advice from adults who are at a bit of a distance, than they are from those who are closest.

In a rite of passage, it’s ideal for the father to remain in a nurturing role, while someone outside of the boy’s most intimate circle is the one who pushes him. The former provides the sense of security that actually gives him the confidence to heed the latter’s challenge to launch out.

At the very bottom of it, a third-party initiator allows for an initiation to occur without the father-son tension getting in the way.

If I look back at my own life, I can see this pattern. My dad was always there for me and set an example for me, but other adult men helped usher me into manhood. Football coaches, professors, and church leaders all played roles in various rites of passage along my developmental journey.

While a father might not be the one exclusively guiding his son’s initiation into manhood, this doesn’t mean he doesn’t have any role in facilitating a rite of passage experience. A dad’s job is to ensure that his son has plenty of opportunities to be mentored and initiated by other men. A father should focus on building a community of men around himself that can serve as a pool of potential initiators; every boy needs three families to grow up well! Surround yourself with the kind of men you’d want to help guide and teach your son. If you want to set up a structured ritual for your son’s transition into manhood, that’s awesome, but ask your male friends and relatives to get involved with it too. Both you and your son will get more out of the experience.