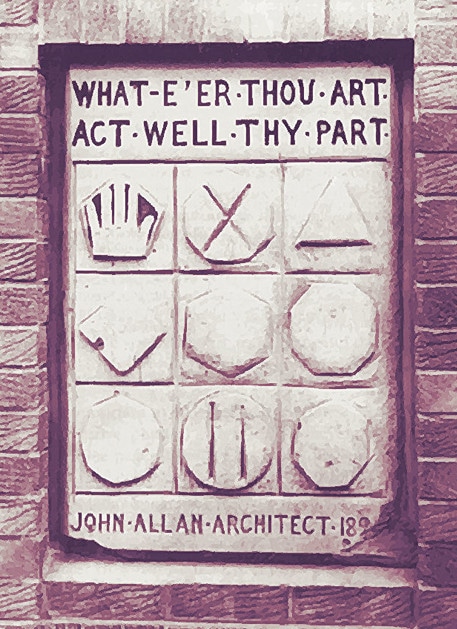

Over the door of a building that sits close to the Stirling Castle in southern Scotland, hangs a curious stone designed by John Allan, a 19th century architect known for his peculiar designs, as well as including inscriptions in his work.

At the top of this particular piece, Allan had carved a quote typically attributed to Shakespeare: “What e’er thou art, act well thy part.” Below the quotation sits a grid of nine squares, each bearing different symbols and shapes.

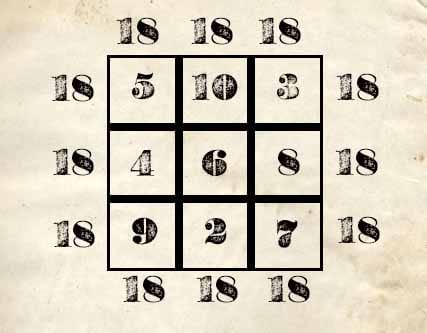

The design forms what is called a “magic square.” Each of the symbols represents a numerical value, and no matter which way you add the numbers up, they always total 18. If any of the numbers are moved or replaced with another, the tiles will no longer add up to 18, and the square will lose its “magic.” Each symbol has an irreplaceable part to play in contributing to the whole.

I have a replica of the Stirling stone sitting in my office. It reminds me that whatever part I have to play in my family, community, or work — whether it’s a big role or a seemingly minor one — it’s up to me to carry out my responsibilities the very best I can. The Stirling stone also reminds me that true happiness and fulfillment in life comes not from being recognized, but from being useful to the world around me.

For any group or culture to function as it was intended and reach its full potential, everyone must pull their own weight, from those doing the “grunt” work to those at the top of the pile. The idea that you should do your best – even in the small and obscure roles of life — isn’t a particularly sexy principle, but one much needed in our world.

All Good Work Is Important

“If a man is called to be a street sweeper, he should sweep streets even as a Michelangelo painted, or Beethoven composed music or Shakespeare wrote poetry. He should sweep streets so well that all the hosts of heaven and earth will pause to say, ‘Here lived a great street sweeper who did his job well.’” – Martin Luther King, Jr.

In our modern life, “acting well thy part” in whatever station life finds you in often takes a back seat to the idea of being “passionate” about what you do. According to this popular notion, to find true meaning and fulfillment, you need to work at something you were “made to do.” If your work doesn’t spring from your “deep inner truth” or if it isn’t fun, then it’s not a job worth doing. In general, the type of work that one can be passionate about is thought to be limited to creative, white-collar careers – tech, art, media, and the like. Leave the other boring and mindless work to the poor unenlightened saps, or so the thinking goes.

But as Dirty Jobs TV host Mike Rowe pointed out in a TED talk, all work has value. And any kind of work – even the “dirty” kind – can bring you happiness, even if you’re not passionate about it. The people he worked with on his show, from road kill retrievers to manure cultivators, were the happiest people he had ever met. Why were they so content? Because, as Rowe intoned before each episode, they earned “an honest living doing the kinds of jobs that make civilized life possible for the rest of us.”

The folks he interacted with didn’t do “sexy” jobs, but they were satisfied in knowing they had an absolutely essential role in keeping society humming along. Like removing a single tile from the magic square, if you take one of these “dirty” jobs out of the equation, things start to fall apart and society no longer “adds up.”

These folks were more concerned about being useful to society than having an “important,” passion-filled job.

The essential nature of work is not limited to those who use a shovel and a pickaxe. Every job big and small, unique or ordinary, when done well, can add to society and enrich the lives of other people. A waiter can think of himself as just someone who serves food to people, or he can think of himself as someone who gives a pair of harried parents welcome relief and enjoyment on their first date night out in a year. A nurse tech can see himself as just cleaning up after patients, or he can see himself as offering encouragement, positivity, and humor to those who are often in pain. We’ve all experienced the huge gap between those who simply do their job, and those who “act well their part.” The latter carry out their responsibilities, whatever they are, to the best of their ability.

American playwright Channing Pollock expounded on this principle 70 years ago:

“Naturally, all of us “want to do something important, but few of us realize that we are probably doing it in our everyday jobs. We have fallen into the habit of thinking that the only important jobs are the “glamor” jobs, or at least the white-collar jobs — the executive jobs. But the essential work of the world isn’t done by jazz-band leaders and radio and movie stars, or even by bond salesmen and our more than three hundred thousand doctors and lawyers. It is done by the man with the hoe and the hammer, by the women who care for those men and their children and their homes, and by millions of other men and women who range from the teacher’s desk to the more coveted desks littered with phones and push buttons.

We are all workmen, and it seems to me that almost any work well done is important. Our civilization is a complicated machine, and machines wouldn’t be worth much if they were made only of shiny gadgets. There must be grease cups and all sorts of “minor” parts. Take out the smallest of these and you’ll soon find that there’s no such thing as a minor part. In the same way, if your water pipes burst, or your telephone goes wrong, or, passing to still more urgent matters, if you found yourself without food or water, you’d discover the plumber, the lineman, the mechanic and the farmer to be just as important as the general manager or the president of the board. Each has his place, and it takes more than a silk hat or a spotlight or a name on the door to make that place vital.

What it takes chiefly, perhaps, is interest and pride in your work. The fellow with a future isn’t often the one who scorns what he is doing at present. He’s the man who thinks his job is important, and so goes on to ever more important jobs.

Few of us understand what a big job a little job may be. The schoolteacher who started Edison thinking about electricity, or laid the mental cornerstones of any other conspicuously or inconspicuously useful citizen, may have said, “What’s being a schoolma’am? I want to do something important.” My friend, Richard, the carpenter, thinks me a very superior person because I lecture and write articles, but we could do better without lectures and articles, perhaps, than without houses. The English poet, Owen Meredith, reminded us that “we may live without books, but civilized man cannot live without cooks” — and that takes in Mr. Richard.

All good work is important. And loyalty, and kindness, and small helpfulness is important, too. There used to be an elevator man at the Lamb’s Club, in New York, who went far out of his way to be pleasant and useful to its members. When he died, not long ago, one of them told me, “Pat’s funeral was our biggest demonstration of respect since the passing of Victor Herbert.” There’s Edgar, the soda-water clerk who used to be at our corner, and who was so full of neighborly advice and eagerness to be everybody’s friend and handyman that we really mourned him when he moved away. My own personal list of important people would include him, and dozens of other friends who are farmers, butchers, bakers, and candlestick makers.

It isn’t your job that counts, but what you do in your job…When President Roosevelt declared we needed fifty thousand planes for national defense, an authority said the problem was to supply ground crews. We all want to fly, but few of us want to tighten bolts. Yet without men to build and repair planes and men to bring fuel the flyer is as earthbound as they, and it isn’t important whether we have fifty thousand pilots or five.

That realization is vital to ourselves, and to progress and survival. I can ruin any morning’s work by asking, ‘What the use of this in a civilization that may be crumbling about our ears?’ I can make the morning glad, and the work good, by answering ‘Civilization won’t crumble while we all do our jobs. If I write as well and honestly as I can, how do I know whom it may help, or how many? How do I know that mine isn’t one of the most important jobs in the world?’

How do you know yours isn’t too?”

Aren’t I Just Settling If I “Act Well Thy Part”?

Some of you might be thinking, “This ‘acting well thy part’ business just sounds like a cop-out for settling. How can I expect to make something of myself if I’m content with my current position?”

“Acting well thy part” doesn’t mean that you must be content with whatever position you currently find yourself in. It doesn’t negate ambition and goal-setting. If you have a job you’re unhappy with, there’s nothing wrong with striving to achieve a better one.

Acting your part well simply means that wherever you are in the moment, you have the integrity to do your best and to be as useful as possible. Yes, you have goals and ambition for the future, but you don’t let them distract from doing a good job now.

Theodore Roosevelt was a living example of the “act well thy part” principle. When he was 36 and serving as a member of the New York City Police Board, he did his job with a gusto that was so uncharacteristic of the position that others wondered if he was already aiming to one day be President of the United States.

When journalist Jacob Riis put that question to TR, Roosevelt had a surprisingly virulent reaction, as a colleague of Riis’ remembered:

“TR leaped to his feet, ran around his desk, and fists clenched, teeth bared, he seemed about to strike or throttle Riis, who cowered away, amazed.

‘Don’t you dare ask me that,’ TR yelled at Riis. ‘Don’t you dare put such ideas into my head. No friend of mind would ever say a thing like that, you—you—’

Riis’ shocked face or TR’s recollection that he had few friends as devoted as Jake Riis halted him. He backed away, came up again to Riis, and put his arm around his shoulder. Then he beckoned me close and in an awed tone of voice explained.

‘Never, never, you must never either of you ever remind a man at work on a political job that he may be president. It almost always kills him politically. He loses his nerve; he can’t do his work; he gives up the very traits that are making him a possibility. I, for instance, I am going to do great things here, hard things that require all the courage, ability, work that I am capable of, and I can do them if I think of them alone.’”

This approach to life was one TR has decided on as a young New York assemblyman a decade earlier:

“At one period I began to believe that I had a future before me, and that it behooved me to be very farsighted and scan each action carefully with a view to its possible effect on that future. This speedily made me useless to the public and an object of aversion to myself; and I then made up my mind that I would not try to think of the future at all, but would proceed on the assumption that each office I held would be the last I ever should hold, and I would confine myself to trying to do my work as well as possible while I held that office.”

Oftentimes we say that once we get our dream position, then we’ll really start trying. But those who do half-ass work in lower level jobs tend to do half-ass work in the big, “important” jobs. If you can’t do simple, menial work and do it well, why would an employer or a client believe you’d be capable of more complex and important work?

I unfortunately know a few men who have failed to realize this principle. They’ve never “acted well their part” in any role they’ve had in work or in life. Consequently, they’ve never been able to achieve the goals or position they believe they truly “deserve.”

Acting Well Thy Part Usually Means Repetition – And That’s Okay

Mike Rowe argues that innovation and imitation are two sides of the same coin, and that the world needs both. We need the thrilling work of creating the new and novel. But we also need to duplicate the component parts of those innovations over and over again in order to keep them running.

We all want lives that allow for some innovation, and yet we all have roles that are mostly imitation – where we are required to do the same thing again and again, day in and day out. But as long as you’re “acting well thy” part you can still find meaning and fulfillment in it.

My dad is a good example of this. He worked as a special agent for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for over 30 years. His job didn’t change all that much over those three decades. Most of the time he was in the office writing memos and reports or preparing evidence for cases. During duck season he would spend his weekends freezing his butt off checking hunters. Despite being highly repetitious and often boring, my dad loved his job.

I asked him how he could do the same seemingly boring or unenjoyable things every day for 30 years and still enjoy it. His answer? “I just took one day at a time and strived to give my very best that day.”

He acted well his part. And it paid off. Not only did he find fulfillment in his work, but he excelled in his career and left a legacy at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as one of its best agents.

As it is in work, so it is in your family. Once you become a dad you quickly learn that parenting is a series of wake up, wash, rinse, and repeat. But you buck up and “act well thy part” as a dad because you’re an irreplaceable part of the “magic square” that is your family. If you fail in your role, your family as a whole will greatly suffer.

How Can You Act Well Thy Part?

My challenge to you today is to “act well thy part” wherever you are in life.

If you’re a young man aiming for the varsity football team, but right now you’re a lowly “scrub” on the scout team, you still have an important role to play in helping the team win by giving your best in practice.

If you’re in a low-level job that doesn’t seem very glamorous, look for the ways, even if they’re small, that you can contribute to and better the lives of those around you.

If you’re dad and husband, don’t let our culture’s emphasis on material and professional success blind you to the fact those are the two most important and fulfilling jobs a man can have. Sure, a lot of the tasks you’ll do aren’t very prestigious, but they’re important.

Finally, if you’re a man, are you acting the part of a true man? Men have a unique role to play in strengthening our society, but too many have shirked the mantle of manhood and we are all suffering for it.

The extent to which every man embraces every part he is given, the important and not so important, and does his best to magnify that role, is the extent to which our families, teams, and communities strengthen and thrive or wither and decay. The world we live in is one giant magic square, and each of has an irreplaceable role to play in contributing to a beautiful whole. In embracing your role in the present moment, no matter how small or mundane, and for however long it lasts, you’ll discover that life is much more meaningful and rewarding.

How will you act well thy part?