Charles Alexander Eastman was born in 1858 and raised as “Ohiyesa” to be a hunter and warrior in the traditional ways of the Santee Sioux. When he was almost 16 years old, he left tribal life to learn the culture of European-American civilization and earn his undergraduate and medical degrees. Eastman became a doctor, a tireless advocate for the rights of his people, and a writer of many works in which he sought to share the true ways of the American Indian. We previously shared Eastman’s insights on the Sioux ideal of manhood. After laying that foundational overview, we then offered edited collections of Eastman’s writing on situational awareness and physical and mental toughness. Today we conclude the series with Eastman’s thoughts on Sioux spirituality.

When Ohiyesa’s father — long presumed to be dead — returned to his native village after spending more than a decade in Canada, he wished to bring his son back to white civilization and teach him the new beliefs and ways of life he had adopted since being away. Ohiyesa was at first greatly apprehensive about leaving the only life he’d ever known, and the new sights and sounds of the towns and ports they traveled to were overwhelming. But there was one thing that duly intrigued the young man and ended up being “perhaps the strongest influence toward my change of heart and complete change of my purpose in life”: his father’s Christian faith. Ohiyesa would end up accepting that faith himself, and change his name to Charles Eastman.

Eastman at first evinced the earnestness and naivety common to converts, trusting his new neighbors and associates wholly, and accepting “civilization and Christianity at their face value.” Yet while he “continued to study the Christ philosophy and loved it for its essential truths,” he began to grow disillusioned with the gap between those truths and the degree they were acted upon. “Christianity is not practiced by the very people who vouch for that wonderful conception of exemplary living,” he ruefully observed. “It appears that they are anxious to pass on their religion to all races of men, but keep very little of it themselves.”

Eastman was disturbed to find that the poor of America lived in filthy urban slums, and that the well-off spent far more time thinking about how to amass more wealth than they did about service or spiritual matters. His faith was particularly challenged when he was called upon to tend to the victims of the massacre at Wounded Knee; the experience proved a “severe ordeal for one who had so lately put all his faith in the Christian love and lofty ideals of white men.”

Eastman eventually found peace in deciding that “Christianity is not at fault for the white man’s sins, but rather the lack of it.” But he also never let go of many of the beliefs and practices with which he’d been raised. In fact, he thought that the tenets of the Sioux religion — which constituted “the basis of all Indian training” — had much to teach Christians and all other citizens of modern civilization. Eastman felt that greed, materialism, and lack of contact with nature left the white man spiritually impoverished and cut off from the powers of wonder and intuition that emanated from the Great Mystery and pervaded all of creation.

Eastman himself, though he moved through the highest levels of civilized society, never lost that connection with spirit. When he wasn’t lecturing or petitioning members of government for the rights of his people, he could be found in a small, primitive cabin on the shores of Lake Huron. He lived out his days close to the divine energies that nourished his soul, and urged all to do likewise.

Below you will find Eastman’s description of the Sioux’s spiritual practices and beliefs. His words speak to men of every creed in our modern, fast-paced, tech-mediated, indoors world, offering inspiration to cultivate greater awe, live more simply, and rediscover the soul-stirring forces all around us.

The Sioux Guide to Spirituality

Worship of the Great Mystery

The original attitude of the American Indian toward the Eternal, the “Great Mystery” that surrounds and embraces us, was as simple as it was exalted. To him it was the supreme conception, bringing with it the fullest measure of joy and satisfaction possible in this life.

The worship of the “Great Mystery” was silent, solitary, free from all self-seeking. It was silent, because all speech is of necessity feeble and imperfect; therefore the souls of my ancestors ascended to God in wordless adoration. It was solitary, because they believed that He is nearer to us in solitude, and there were no priests authorized to come between a man and his Maker. None might exhort or confess or in any way meddle with the religious experience of another. Among us all men were created sons of God and stood erect, conscious of their divinity. Our faith might not be formulated in creeds, nor forced upon any who were unwilling to receive it; hence there was no preaching, proselyting, nor persecution, neither were there any scoffers or atheists.

There were no temples or shrines among us save those of nature. Being a natural man, the Indian was intensely poetical. He would deem it sacrilege to build a house for Him who may be met face to face in the mysterious, shadowy aisles of the primeval forest, or on the sunlit bosom of virgin prairies, upon dizzy spires and pinnacles of naked rock, and yonder in the jeweled vault of the night sky! He who enrobes Himself in filmy veils of cloud, there on the rim of the visible world where our Great-Grandfather Sun kindles his evening campfire, He who rides upon the rigorous wind of the north, or breathes forth His spirit upon aromatic southern airs, whose war-canoe is launched upon majestic rivers and inland seas—He needs no lesser cathedral!

An Evergreen Sense of Wonder and Awe

Naturally magnanimous and open-minded, the red man prefers to believe that the Spirit of God is not breathed into man alone, but that the whole created universe is a sharer in the immortal perfection of its Maker.

The elements and majestic forces in nature, Lightning, Wind, Water, Fire, and Frost, were regarded with awe as spiritual powers, but always secondary and intermediate in character. We believed that the spirit pervades all creation and that every creature possesses a soul in some degree, though not necessarily a soul conscious of itself. The tree, the waterfall, the grizzly bear, each is an embodied Force, and as such an object of reverence.

[The American Indian] saw miracles on every hand—the miracle of life in seed and egg, the miracle of death in lightning flash and in the swelling deep! Nothing of the marvelous could astonish him; as that a beast should speak, or the sun stand still. The virgin birth would appear scarcely more miraculous than is the birth of every child that comes into the world, or the miracle of the loaves and fishes excite more wonder than the harvest that springs from a single ear of corn.

If we are of the modern type of mind, that sees in natural law a majesty and grandeur far more impressive than any solitary infraction of it could possibly be, let us not forget that, after all, science has not explained everything. We have still to face the ultimate miracle—the origin and principle of life! Here is the supreme mystery that is the essence of worship, without which there can be no religion, and in the presence of this mystery our attitude cannot be very unlike that of the natural philosopher, who beholds with awe the Divine in all creation.

Now we see at once the root of the red man’s failure to approach even distantly the artistic standard of the civilized world. It lies not in the lack of creative imagination—for in this quality he is a born artist—it lies rather in his point of view. I once showed a party of Sioux chiefs the sights of Washington, and endeavored to impress them with the wonderful achievements of civilization. After visiting the Capitol and other famous buildings, we passed through the Corcoran Art Gallery, where I tried to explain how the white man valued this or that painting as a work of genius and a masterpiece of art. “Ah!” exclaimed an old man, “such is the strange philosophy of the white man! He hews down the forest that has stood for centuries in its pride and grandeur, tears up the bosom of mother earth, and causes the silvery watercourses to waste and vanish away. He ruthlessly disfigures God’s own pictures and monuments, and then daubs a flat surface with many colors, and praises his work as a masterpiece!”

The Indian did not paint nature, not because he did not feel it, but because it was sacred to him. He so loved the reality that he could not venture upon the imitation.

Kinship with Animals

The Indian loved to come into sympathy and spiritual communion with his brothers of the animal kingdom, whose inarticulate souls had for him something of the sinless purity that we attribute to the innocent and irresponsible child. He had faith in their instincts, as in a mysterious wisdom given from above; and while he humbly accepted the supposedly voluntary sacrifice of their bodies to preserve his own, he paid homage to their spirits in prescribed prayers and offerings.

In hunting songs, the leading animals are introduced; they come to the boy to offer their bodies for the sustenance of his tribe. The animals are regarded as his friends, and spoken of almost as tribes of people, or as his cousins, grandfathers and grandmothers.

Man’s spirit may live with the beasts before he is born a man. He will then know the animal language but he cannot tell it in human speech. He always retains his sympathy with them, and can converse with them in dreams.

Family as the Basic Unit of Religion

The American Indian was an individualist in religion as in war. He had neither a national army nor an organized church. There was no priest to assume responsibility for another’s soul. That is, we believed, the supreme duty of the parent, who only was permitted to claim in some degree the priestly office and function, since it is his creative and protecting power which alone approaches the solemn function of Deity.

The distinctive work of both grandparents is that of acquainting the youth with the national traditions and beliefs. It is reserved for them to repeat the time-hallowed tales with dignity and authority, so as to lead him into his inheritance in the stored-up wisdom and experience of the race. The old are dedicated to the service of the young, as their teachers and advisers, and the young in turn regard them with love and reverence.

A Young Man’s Religious Rite of Passage

That solitary communion with the Unseen which was the highest expression of our religious life is partly described in the word hambeday, literally “mysterious feeling,” which has been variously translated “fasting” and “dreaming.” It may better be interpreted as “consciousness of the divine.”

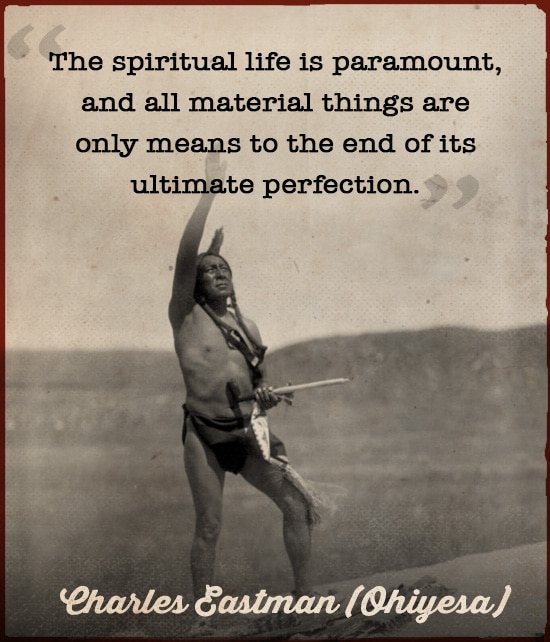

The first hambeday, or religious retreat, marked an epoch in the life of the youth, which may be compared to that of confirmation or conversion in Christian experience. Having first prepared himself by means of the purifying sweat lodge, and cast off as far as possible all human fleshly influences, the young man sought out the noblest height, the most commanding summit in all the surrounding region. Knowing that God sets no value upon material things, he took with him no offerings or sacrifices other than symbolic objects, such as paints and tobacco. Wishing to appear before Him in all humility, he wore no clothing save his moccasins and breechclout.

At the solemn hour of sunrise or sunset he took up his position, overlooking the glories of earth and facing the “Great Mystery,” and there he remained, naked, erect, silent, and motionless, exposed to the elements and forces of His arming, for a night and a day to two days and nights, but rarely longer. Sometimes he would chant a hymn without words, or offer the ceremonial “filled pipe.” In this holy trance or ecstasy the Indian mystic found his highest happiness and the motive power of his existence.

When he returned to the camp, he must remain at a distance until he had again entered the sweat lodge and prepared himself for intercourse with his fellows. Of the vision or sign vouchsafed to him he did not speak, unless it had included some commission which must be publicly fulfilled. Sometimes an old man, standing upon the brink of eternity, might reveal to a chosen few the oracle of his long-past youth.

Marriage as the Apotheosis of Spirituality

It appears that where marriage is solemnized by the church and blessed by the priest, it may at the same time be surrounded with customs and ideas of a frivolous, superficial, and even prurient character. We believed that two who love should be united in secret, before the public acknowledgment of their union, and should taste their apotheosis with nature. The betrothal might or might not be discussed and approved by the parents, but in either case it was customary for the young pair to disappear into the wilderness, there to pass some days or weeks in perfect seclusion and dual solitude, afterward returning to the village as man and wife. An exchange of presents and entertainments between the two families usually followed, but the nuptial blessing was given by the High Priest of God, the most reverend and holy Nature.

The Power of Solitude

I distinctly recall one occasion when [my grandmother] took me with her into the woods in search of certain medicinal roots.

“Why do you not use all kinds of roots for medicines?” said I.

“Because,” she replied, in her quick, characteristic manner, “the Great Mystery does not will us to find things too easily. In that case everybody would be a medicine-giver, and Ohiyesa must learn that there are many secrets which the Great Mystery will disclose only to the most worthy. Only those who seek him fasting and in solitude will receive his signs.”

With this and many similar explanations she wrought in my soul wonderful and lively conceptions of the “Great Mystery” and of the effects of prayer and solitude.

It was not, then, wholly from ignorance or improvidence that [American Indian] failed to establish permanent towns and to develop a material civilization. To the untutored sage, the concentration of population was the prolific mother of all evils, moral no less than physical. He argued that food is good, while surfeit kills; that love is good, but lust destroys; and not less dreaded than the pestilence following upon crowded and unsanitary dwellings was the loss of spiritual power inseparable from too close contact with one’s fellow-men. All who have lived much out of doors know that there is a magnetic and nervous [vigorous] force that accumulates in solitude and that is quickly dissipated by life in a crowd; and even his enemies have recognized the fact that for a certain innate power and self-poise, wholly independent of circumstances, the American Indian is unsurpassed among men.

The Necessity of Daily Prayer

In the life of the Indian there was only one inevitable duty—the duty of prayer—the daily recognition of the Unseen and Eternal. His daily devotions were more necessary to him than daily food. He wakes at daybreak, puts on his moccasins and steps down to the water’s edge. Here he throws handfuls of clear, cold water into his face, or plunges in bodily. After the bath, he stands erect before the advancing dawn, facing the sun as it dances upon the horizon, and offers his unspoken orison. His mate may precede or follow him in his devotions, but never accompanies him. Each soul must meet the morning sun, the new, sweet earth, and the Great Silence alone!

Whenever, in the course of the daily hunt, the red hunter comes upon a scene that is strikingly beautiful and sublime—a black thunder-cloud with the rainbow’s glowing arch above the mountain; a white waterfall in the heart of a green gorge; a vast prairie tinged with the blood-red of sunset—he pauses for an instant in the attitude of worship. He sees no need for setting apart one day in seven as a holy day, since to him all days are God’s. Every act of his life is, in a very real sense, a religious act. He recognizes the spirit in all creation, and believes that he draws from it spiritual power.

His respect for the immortal part of the animal, his brother, often leads him so far as to lay out the body of his game in state and decorate the head with symbolic paint or feathers. Then he stands before it in the prayer attitude, holding up the filled pipe, in token that he has freed with honor the spirit of his brother, whose body his need compelled him to take to sustain his own life. When food is taken, the woman murmurs a “grace” as she lowers the kettle; an act so softly and unobtrusively performed that one who does not know the custom usually fails to catch the whisper: “Spirit, partake!” As her husband receives the bowl or plate, he likewise murmurs his invocation to the spirit.

Simplicity and Generosity

The native American has been generally despised by his white conquerors for his poverty and simplicity. They forget, perhaps, that his religion forbade the accumulation of wealth and the enjoyment of luxury. To him, as to other single-minded men in every age and race, from Diogenes to the brothers of Saint Francis, from the Montanists to the Shakers, the love of possessions has appeared a snare, and the burdens of a complex society a source of needless peril and temptation. Furthermore, it was the rule of his life to share the fruits of his skill and success with his less fortunate brothers. Thus he kept his spirit free from the clog of pride, cupidity, or envy, and carried out, as he believed, the divine decree—a matter profoundly important to him.

The public or tribal position of the Indian is entirely dependent on his private virtue, and he is never permitted to forget that he does not live to himself alone, but to his tribe and his clan.

The public or tribal position of the Indian is entirely dependent on his private virtue, and he is never permitted to forget that he does not live to himself alone, but to his tribe and his clan.

The Indian, in his simple philosophy, was careful to avoid a centralized population, wherein lies civilization’s devil. He would not be forced to accept materialism as the basic principle of his life, but preferred to reduce existence to its simplest terms. His roving out-of-door life was more precarious, no doubt, than life reduced to a system, a mechanical routine; yet in his view it was and is infinitely happier. To be sure, this philosophy of his had its disadvantages and obvious defects, yet it was reasonably consistent with itself, which is more than can be said for our modern civilization. He knew that virtue is essential to the maintenance of physical excellence, and that strength, in the sense of endurance and vitality, underlies all genuine beauty. He was as a rule prepared to volunteer his services at any time in behalf of his fellows, at any cost of inconvenience and real hardship, and thus to grow in personality and soul-culture. Generous to the last mouthful of food, fearless of hunger, suffering, and death, he was surely something of a hero. Not “to have,” but “to be,” was his national motto.

The Indian, in his simple philosophy, was careful to avoid a centralized population, wherein lies civilization’s devil. He would not be forced to accept materialism as the basic principle of his life, but preferred to reduce existence to its simplest terms. His roving out-of-door life was more precarious, no doubt, than life reduced to a system, a mechanical routine; yet in his view it was and is infinitely happier. To be sure, this philosophy of his had its disadvantages and obvious defects, yet it was reasonably consistent with itself, which is more than can be said for our modern civilization. He knew that virtue is essential to the maintenance of physical excellence, and that strength, in the sense of endurance and vitality, underlies all genuine beauty. He was as a rule prepared to volunteer his services at any time in behalf of his fellows, at any cost of inconvenience and real hardship, and thus to grow in personality and soul-culture. Generous to the last mouthful of food, fearless of hunger, suffering, and death, he was surely something of a hero. Not “to have,” but “to be,” was his national motto.

The Legacy of the American Indian

In the mad rush for wealth we have too long overlooked the foundations of our national welfare. The contribution of the American Indian, though considerable from any point of view, is not to be measured by material acquirement. Its greatest worth is spiritual and philosophical. He will live, not only in the splendor of his past, the poetry of his legends and his art, not only in the interfusion of his blood with yours, and his faithful adherence to the new ideals of American citizenship, but in the living thought of the nation.

Read the Entire Series:

Lessons from the Sioux in How to Turn a Boy into a Man

The Sioux Guide to Situational Awareness

The Sioux Guide to Mental and Physical Toughness

__________________________________________

Sources and Further Reading: