Editor’s note: The following excerpt was taken from the chapter “How to Plan to Produce,” included in The Technique of Getting Things Done (1947) by Donald Laird.

“You taught me one of the most useful things I ever learned,” a former student, now vice-president of a nationwide corporation, told me.

I preened as I waited for him to return some of my own pearls of wisdom.

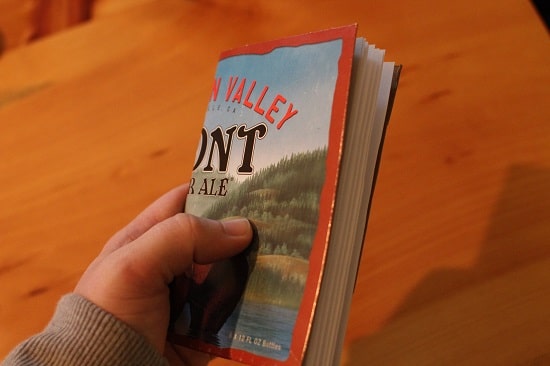

“I learned it by watching you,” he continued, pulling a 2-cent pad from his vest pocket. “We noticed that you often wrote something on one of these pads, then tore off the little sheet and filed it in a stack clipped to the back of the pad. Occasionally you would remove the top sheet, crumple it, and toss it into the wastebasket.

“The class was making bets about that pad. Someone even suggested you were writing poetry on it. I snooped in the wastebasket and found that the slips contained businesslike orders to yourself about things you had to do.

“I had forgotten about your pad until a few years ago. I was behind in my work and forgetting a lot of small but important things. So I bought a 2-cent pad and tried your scheme. I made notes the instant I found something needed to be done. Used a separate sheet for each thing and arranged them in the order in which they could be done quickest.

“Then I started getting things done.”

There is nothing original about this little arrangement, but it is extremely effective, for it is a written plan of one’s own activities.

Devotees of the Pad

Young Harry Heinz, of Pittsburgh, carried a pocket pad as he peddled his homemade horseradish. His ideas, his orders to himself, were jotted down as he went and organized later in the day. This planning was the backbone of his self-supervision; it enabled him to build up the food-packing business which became famous under the slogan “57 Varieties.” He had jotted that slogan down while riding on a New York City elevated train.

A canal-toll collector in Dayton knew the use of planning, too. He even kept a pad beside his bed. This young fellow, John H. Patterson, was one of the “gettingest-done” men of all time. He called his sheaf of notes “Things to Do Today.” He built up the gigantic National Cash Register Company from scratch.

Victor Hugo always supervised himself by a little pad of notes. He kept the pad beside him night and day.

Leonardo da Vinci started the note-pad habit in his youth and kept it up through his old age. He carried his pad in his belt.

Bismarck used blank sheets and kept them between the leaves of his prayer book.

Lord Bacon called his paper plans “Sudden Thoughts Set Down for Use.”

Beethoven was never without a planning pad; it was almost the only systematic thing about his life.

John Hunter, a carpenter, could barely read and write when he was twenty, but he became one of the world’s leading surgeons and anatomists. He used a note pad to plan his work, to jog himself into getting things done.

“My rule,” Hunter said, “is deliberately to consider, before I commence, whether it is practicable. If it be practicable, I can accomplish it if I give sufficient pains to it and having begun, I never stop until it is done.”

Use a pocket pad to write down the things you should do. Make a note the instant an idea hits you or an order is given. Organize your notes so that one job will logically follow another. Then you will not lose time wondering what to do next or waiting to be told.

Read More on Pocket Notebooks: