I love a good maxim.

The ability to encapsulate a profound truth or insight in as few words as possible is a talent I really admire. Such dense nuggets of wisdom are easy to digest and yet really get you thinking. For that reason, we’ve previously highlighted the maxims of 17th-century Jesuit priest Baltasar Gracián, the sayings of old Benjamin Franklin, and the time-worn aphorisms that have been taught and shared for so long, no one’s sure where they originated.

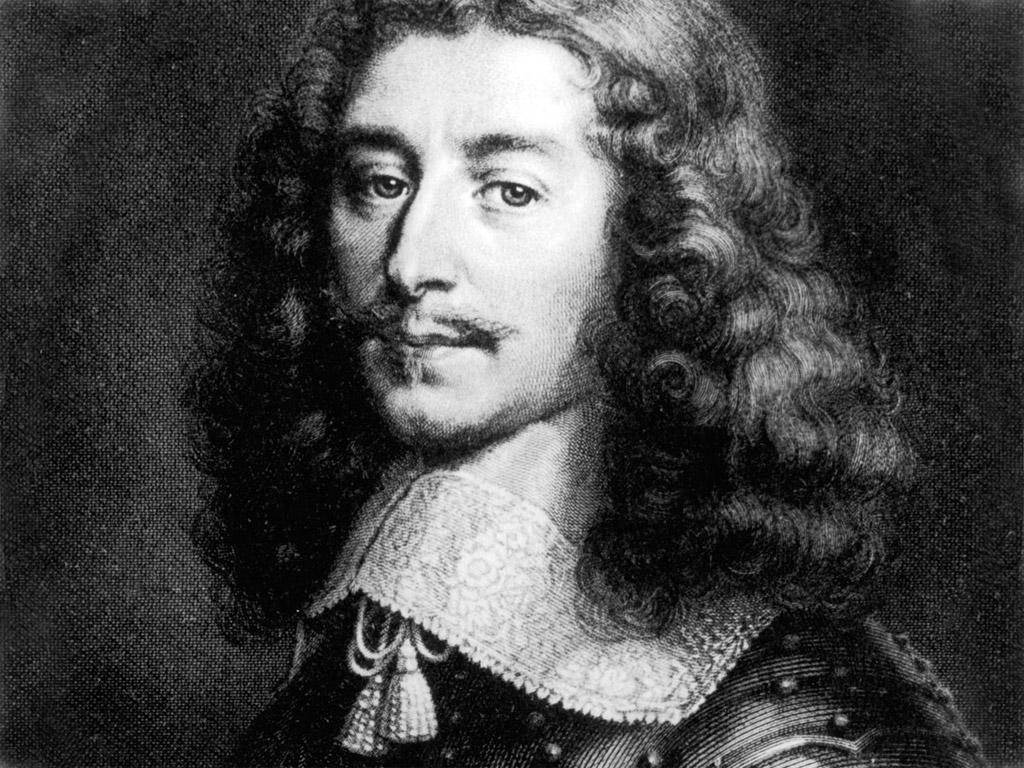

Another one of my favorite aphoristic writers was a contemporary of Gracián: French nobleman Francois de La Rochefoucauld.

The aristocratic La Rochefoucauld was born into wealth during a time in which the French royal court vacillated between aiding and threatening the noble class. During the mid-1640s, the French king (Louis XIV) was just a child, and his mother and other members of the royal court ruled in his stead. Oftentimes they executed policies that were in their own self-interest, and which reduced the power and independence of the nobility. In response, the nobility rebelled. From 1648 until 1653 France descended into a civil war between the noblemen and the bureaucrats of the royal court — battles that became known as the Fronde. La Rochefoucauld was one of the leading rebel noblemen during these wars. His father died fighting in the Fronde in 1650 and he himself was shot through the head. He was blinded from the headshot, but made a miraculous recovery and eventually regained full vision.

Despite their best efforts, the noblemen lost, and La Rochefoucauld retired to his country estate where he wrote and took part in the salon of Madeleine de Souvré, marquise de Sablé. Like many noblemen who fought in the Fronde, La Rochefoucauld wrote his memoirs. But he also spent a great deal of his time and energy on a collection of aphorisms that he entitled Maximes.

Maximes consists of hundreds of two- or three-line sentences in which La Rochefoucauld muses about honor, fate, friendship, love, and the human tendency for self-delusion. His experience with the royal court during the Fronde influenced his Maximes immensely. He saw firsthand the conniving and social duplicity that went on amongst members of the royal court and observed that often in life it isn’t the virtuous, but rather the cunning and lucky who succeeds. Like many French classical writers, La Rochefoucauld glorified strength of body and character, and despised weakness. It’s no surprise then that Nietzsche was highly influenced by him and tried to imitate his aphoristic style.

When you read La Rochefoucauld’s Maximes, you’re taken aback about how modern they seem. I sometimes forget I’m reading lines penned over 355 years ago. This is partly due to the fact that they are interlaced with a certain cynicism. In fact, Maximes offended some of La Rochefoucauld’s contemporaries who felt his cynicism was intended as a knock against traditional scruples and morality. But La Rochefoucauld himself was in fact an idealist who always led a very upright and virtuous life — sticking with his principles even when they got him into social and political trouble. His maxims were not then intended to inspire others to live in a strictly Machiavellian way, but rather to move readers towards greater self-awareness, and an understanding of the motives of others as to not be ensnared by their traps and temptations. In short, he was trying to figure out how to live one’s ideals in a backstabbing world where people are often not as they seem, and cannot even recognize their tendency to manipulate others and deceive themselves.

I like thumbing through the maxims of La Rochefoucauld every now and then when I feel like I’m getting too full of myself. His maxims remind me that oftentimes success in life comes through mere luck and that Lady Luck is a fickle dame. What’s more, his keen insights about human psychology remind me that the easiest person to fool is usually yourself, so always question the narratives you’re telling yourself, about yourself.

Below I offer a collection of my favorite maxims from the 504 that La Rochefoucauld penned. Hopefully they will give you a taste of his style, as well as insights on how to more deftly navigate a world that still remarkably resembles the machinations of a French royal court.

The Maxims of Francois de La Rochefoucauld

No one deserves to be praised for kindness if he does not have the strength to be bad; every other form of kindness is most often merely laziness or lack of willpower.

A man is truly honorable if he is willing to be perpetually exposed to the scrutiny of honorable people.

The person who lives without folly is not as wise as he thinks.

We receive less gratitude than we expect when we are gracious, because the giver’s pride and the recipient’s pride cannot agree on the value of the favor.

We often annoy other people when we think we could not possibly annoy them.

Fortunate people rarely correct their faults; they always think they are right while fortune is favoring their evil conduct.

Nothing is so contagious as example, and we never do very good deeds or very evil ones without producing imitations. We copy the good deeds in a spirit of emulation, and the bad ones because of the malignity of our nature — which shame used to hold under lock and key, but an example sets free.

It is more often pride than lack of enlightenment that makes us oppose so stubbornly the generally accepted view of something. We find the front seats already taken on the correct side, and we do not want any of the back ones.

Few things are impossible in themselves; we lack the diligence to make them succeed, rather than the means.

There are some people whose faults become them well, while other people, with all their good qualities, are lacking in charm.

Humility is often merely a pretense of submissiveness, which we use to make other people submit to us. It is an artifice by which pride debases itself in order to exalt itself; and though it can transform itself in thousands of ways, pride is never better disguised and more deceptive than when it is hidden behind the mask of humility.

Good taste is due more to judgement than to intelligence.

Politeness is a desire to receive it in return, and to be thought civil.

Small-mindedness leads to stubbornness; it is hard for us to believe anything that goes beyond what we see.

We are deceiving ourselves if we think that only the violent passions, such as ambition and love, can conquer the others. Laziness, sluggish though it is, often manages to dominate them; it wrests from us all of life’s plans and deeds, where it imperceptibly destroys and devours the passions and virtues alike.

We take exception to judges for the most trivial of interests, yet we are quite willing to let our reputation and glory depend on the judgement of men who are utterly opposed to us, because of either jealousy or self-absorption or lack of enlightenment; and it is merely to have them decide in our favor that we risk our peace of mind and our very life in so many ways.

Hardly any man is clever enough to know all the evil he does.

Honors won are down payments for those still to be won.

There are people who have the approval of society, though their only merits are the vices useful for the transactions of daily life.

Often, the pride that rouses so much envy also helps us to mitigate it.

Sometimes it takes as much cleverness to profit from good advice as to give ourselves good advice.

There are some wicked people who would be less dangerous if they had absolutely no goodness.

Some business matters and some illnesses can be aggravated by remedies, at certain times; the really clever thing is to know when it is dangerous to make use of them.

A pretense of simplicity is a subtle imposture.

There are more faults of temperament than of mind.

We always like those who admire us, and we do not always like those whom we admire.

We are very far from knowing all our wishes.

Some follies are catching, like contagious illnesses.

Plenty of people disdain possessions, but few know how to give them away.

It is usually only in matters of little interest that we take the risk of not believing in appearances.

Whatever good is said about us never teaches us anything new.

We often forgive those who bore us, but we cannot forgive those whom we bore.

Sometimes in life there are events that you need to be a little foolish to handle.

The reason why lovers are never bored with each other’s company is because they are always talking about themselves.

The extreme pleasure we take in talking about ourselves should make us afraid that we may scarcely be giving any to our listeners.

What usually prevents us from showing the depths of our hearts to our friends is not so much mistrust of them as mistrust of ourselves.

Weak people cannot be sincere.

We cannot long feel as we should toward our friends and benefactors if we allow ourselves the liberty of talking frequently about their faults.

Only those who deserve disdain are afraid of being treated with disdain.

We confess small faults only to convince people that we have no greater ones.

Envy is harder to appease than hatred.

We sometimes think we hate flattery, but what we hate is merely the way it is done.

When our hatred is too intense, it puts us on a lower level than those we hate.

We feel our good and ill fortune only in proportion to our self-love.

To be a great man, you must know how to take advantage of every turn of fortune.

Most men, like plants, have hidden characteristics that are revealed by chance.

We find very few sensible people except those who agree with our own opinion.

What makes us so bitter against people who act cunningly is the fact that they think they are cleverer than we are.

We are nearly always bored with the people whose company should not bore us.

Little minds are too easily wounded by little things; great minds see all such things without being wounded by them.

Humility is the true test of the Christian virtues: without it, we retain all our faults, and they are merely covered by pride, which hides them from other people and often from ourselves.

People are discredited much more, in our eyes, by the slight infidelities they do to us, than by the greater ones they do to other people.

Injuries done to us by others often cause us less pain than those that we do to ourselves.

However we may mistrust the sincerity of those who talk to us, we always think they are more truthful with us than with other people.

Very few cowards consistently know the full extent of their fears.

Most young people think they are being natural when they are merely uncivil and uncouth.

Average minds usually condemn whatever is beyond their grasp.

Fortune reveals our virtues and vices, just as light reveals objects.

Nobody is more often wrong than someone who cannot bear being wrong.

We ought to treat fortune like health: enjoy it when it is good, be patient when it is bad, and never use drastic remedies except in a case of absolute necessity.

The hardest task in a friendship is not to disclose our faults to our friend, but to make him see his own.

Nearly all of our faults are more forgivable than the means we use to hide them.

Whatever shame we may have earned, it is almost always in our power to re-establish our reputation.

We often think we are being constant in a time of misfortune when we are merely downcast and endure it without daring to face it.

Confidence contributes more to conversation than intelligence does.

Few people know how to be old.

We pride ourselves on faults that are opposite to those we really have; when we are weak, we boast that we are being stubborn.

We readily forgive our friends for faults that do not affect us.

Nothing prevents us from being natural as much as the wish to look natural.

We should not judge a man’s merit by his great qualities, but by the use he makes of them.

Weakness is more opposed to virtue than vice is.

When fortune catches us by surprise and gives us a position of greatness without having led us to it step by step, and without our having hoped for it, it is almost impossible to fill it well and seem worthy of holding it.

The same pride that makes us criticize the faults we think we do not have, also leads us to feel disdain for the good qualities we do not have.

There is often more pride than kindness in our pity for our enemies’ misfortunes; we show them signs of compassion in order to make them feel how superior to them we are.

We never desire passionately what we desire by reason alone.

However rare true love may be, true friendship is even rarer.

Our envy always lasts longer than the good fortune of those we envy.

We usually slander out of vanity rather than malice.

Quarrels would not last long if the fault was only on one side.

It is more vital to study men than books.

We criticize ourselves only to be praised.

Only people with some strength of character can be truly gentle: usually, what seems like gentleness is mere weakness, which readily turns to bitterness.

Virtues are lost in self-interest as rivers are lost in the sea.