This is the third part of a series on the archetypes of mature masculinity based on the book King, Warrior, Magician, Lover by Robert Moore and Douglas Gillette. If you haven’t already, I highly recommend reading the introduction to the series first. Also, keep in mind that these posts are a little more esoteric than our normal fare, and are meant to be contemplated and thoughtfully reflected upon.

As you may remember, the boyhood archetypes are positive but immature energies that, with proper masculine guidance, develop into the archetypes of mature manhood. Last time we talked about two of the four boyhood archetypes–the Divine Child and the Precocious Child–suggested by Moore and Gillette. Today we’ll talk the other two–the Oedipal Child and the Hero. Let’s just dive right into it.

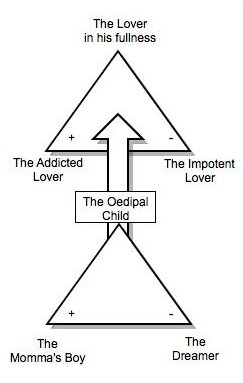

The Oedipal Child

Did you initially recoil a little when you read the name of this archetype? It’s easy to read “Oedipal Child” and think “Oedipus Complex.” You know, Freud’s idea that boys have a repressed sexual desire for their mothers. Yuck, right? Well, hold on a sec.

Did you initially recoil a little when you read the name of this archetype? It’s easy to read “Oedipal Child” and think “Oedipus Complex.” You know, Freud’s idea that boys have a repressed sexual desire for their mothers. Yuck, right? Well, hold on a sec.

True, Moore does argue that a boy’s yearning for “the nurturing, infinitely good, infinitely beautiful Mother,” is at the root of this archetype. But this longing is not for a boy’s actual mother, but rather for the feminine energy of the “Great Mother–the Goddess in her many forms in the myths and legends of many peoples and cultures.”

Okay, that probably doesn’t help very much either. This is one of those places where Moore and Gillette get a little too New Agey for me, and where their prose can put distance between their ideas and many modern men.

The way I think of the Oedipal Child archetype is to relate it to the philosophy of the Romantic period, which I really enjoy. Think Ralph Waldo Emerson. The Romantics explored their inner life, celebrating the power of imagination and intuition, seeking to feel and experience life deeply, and extolling the virtues of passion and free expression. They sought to tap into the energy that emanated from Mother Nature. The Oedipal Child archetype also gives a boy the desire to forge relationships with others and the affection and warmth to nurture those relationships. Thus at the heart of this archetypes is the desire for connection–a connection with oneself, with the deeper forces of life, with nature, and with other people. In this way, the Oedipal Child archetype contains the seeds of a man’s spirituality.

See? It’s a good thing! At least when it’s nurtured into the mature Lover archetype by masculine energy. If it’s not–these shadows are the result:

The Shadows of the Oedipal Child

The Mama’s Boy. Instead of tapping into the positive feminine energy associated with “the Great Mother,” the Mama’s Boy fixates on the energy as embodied by his real mother (and other women); he is too connected to his mom. Jung would argue that this shadow archetype takes control when there is no father, or a weak father in the home.

The Mama’s Boy shadow manifests itself in various ways. The most obvious is the boy (or man) who’s “tied to Mama’s apron strings.” He never wants to offend, hurt, or worry his mother. He lives to please dear old mom, even if that means putting her desires and wishes above his own. Nothing gives him more satisfaction than hearing his mom say, “That’s a good boy.”

Many men never break out from under the influence of the Mama’s Boy shadow. They always acquiesce to their mother’s wishes and put what mom wants ahead of what their wives want (and what they themselves want). These men never learn that man was made to leave his mother and father and cleave unto his wife only.

Other ways the Mama’s Boy shadow rears its ugly head in adult men is womanizing and excessive porn use. An overbearing desire for union with one’s mother and a failure to harness feminine energy in a healthy way will result in a man looking to fill that void and find that connection in mere mortal women. But of course mortal women can never fill that role as the Mother archetype. So a man under the power of the Mama’s Boy shadow moves from failed relationship to failed relationship or spends countless hours each week looking at porn in hopes that he’ll find a woman who’ll fulfill his need.

The Dreamer. The passive shadow of the Oedipal Child archetype is the Dreamer. Instead of seeking connection with others (especially with Mother), the Dreamer is aloof. While the positive Oedipal Child archetype fuels a boy’s spirituality, the Dreamer pushes this desire for other-worldliness to an extreme. He cuts himself off from human relationships because he would rather be alone with his thoughts. While there’s certainly nothing wrong with introspection and solitude, the boy under the influence of the Dreamer shadow too often has his head in the clouds and drifts away from reality. He spends too much time dreaming, and not enough time learning how to have relationships with other people, and thus developing the social skills needed to make his dreams comes true. He is stunted and unconnected.

Accessing the Oedipal Child Archetype as a Man

A man who has successfully integrated the Oedipal Child into his psyche understands the gentle part of being a gentleman. He can be warm, even “sweet” with others, and he can be introspective and spiritual while still keeping his feet on the ground. He isn’t afraid to tap into “feminine” energy, but he isn’t dominated by it either. He loves his mother, and has learned much from her, but he is decidedly his own man.

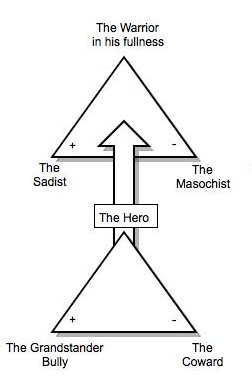

The Hero

Think back to when you were a teenager. Remember that feeling of expanding independence? Little by little you started to rely less and less on your parents for your basic needs. You clamored for more freedoms and for your parents to get off your back.

Think back to when you were a teenager. Remember that feeling of expanding independence? Little by little you started to rely less and less on your parents for your basic needs. You clamored for more freedoms and for your parents to get off your back.

Also, if you were like most teenage boys, you probably took part in activities (sometimes very risky activities) to test your mettle and your ability to overcome fear. You wanted to prove to your friends, and more importantly to yourself, that you were “man enough” to take on any challenge that came your way.

When I was in Vermont a few years ago, Kate and I went to this swimming hole in the woods. The water was cold and deep and was surrounded by sheer cliffs. It was perfect for cliff diving, but still pretty treacherous. While Kate and I swam, we watched a group of teenage boys dive from the highest point of the cliff into the water below. Every dive became more elaborate and dangerous.

Kate elbowed me and asked “So, are you going to jump?”

“Nope.”

I was suddenly struck with the feeling of being old. I thought back to the time when I was a teenager camping in New Mexico with some friends. We found a lake with 40 foot sheer cliffs and spent the afternoon jumping, flipping, and diving into the deep water below. We pushed ourselves to do ever more daring jumps. We wanted to test ourselves. Now here I was 13 years later and I was content just swimming along the edge, watching these young men hurtle themselves into the air and plummet into the water.

That desire for independence we all had as young men and that almost reckless abandon those boys in Vermont had are manifestations of the Hero archetype.

The Hero archetype is unarguably the most common figure found in myths. Joseph Campbell detailed the use of the Hero archetype in his seminal work, The Hero With a Thousand Faces. In that book, Campbell describes an archetypal journey that all mythological heroes must take. Star Wars is a perfect example of the Hero’s Journey. Luke Skywalker begins the story as a mere “farm boy” on the planet Tatooine. By the end of the first trilogy he has morphed into a Hero who saves the galaxy from evil.

While we’re accustomed to thinking of becoming a hero as the end-all of existence, Moore argues that the hero archetype is still an immature energy that must be further developed into the mature Warrior archetype. Unlike the mature Warrior who fights and battles for a cause bigger than himself, the immature Hero fights and battles mainly for himself. The Hero definitely has ideals–but these ideals are used for a self-serving purpose–to create an identity that facilitates the process of becoming his own man. When you were a teenager, you probably latched onto an identity like this–you were the super-liberal guy, or the super-Christian guy, or the non-comformist Goth guy, and so on. The Hero’s only goal is to win his personal independence, break free from the feminine influence of his mother, and enter fully into manhood. Moreover, while the mature Warrior knows his limitations, the Hero doesn’t have that sort of self-awareness which often results in physical or emotional ruin.

The Hero is usually the last of the boyhood archetypes to develop and is the peak of psychological development in boys. It is the last developmental stage before a boy transitions into manhood. According to Moore, this transformation from boy to man can only occur through the “death” of the Hero. Through initiation and rites of passage, the boy is symbolically killed only to be reborn as a man. Unfortunately, because many men in the modern West lack a rite of passage into manhood, they remain psychologically stuck in adolescence.

The Shadows of the Hero Archetype

The Grandstander Bully. The young man under the influence of the Grandstander Bully demands respect from others and will unleash his wrath both physically and verbally if he doesn’t get it. He has let the Hero’s sense of invulnerability mushroom into an arrogant and inflated sense of self. Thus the boy under the Bully shadow takes unnecessary and foolish risks, and his hubris oftentimes leads to his own destruction.

This shadow very often follows a boy into manhood. Do you know a grown man who suffers from intense road rage or blows up at the waitress who gets his order wrong? That’s the boyhood bully shadow at work. The man who is still haunted by this shadow believes he is superior to all others, and when his inflated sense of self is threatened–ie., when the world does not cater to his needs–he loses his temper and lashes out.

But underneath the Grandstander Bully’s posturing and false bravado lies an insecure coward, and he must fight to keep this fact hidden from everyone else. This insecurity makes the Grandstander Bully sensitive to any insinuation that he isn’t man enough, and so he lacks the confidence to incorporate any “feminine” energy into his life. This is the man who who scoffs at meditation or introspection as “sissy” stuff.

The Coward. The passive polar shadow of the Hero archetype is the Coward. Lacking the Hero’s courage, the boy under this shadow avoids confrontation; whether the conflict is physical or mental or moral, the Coward cannot stand up for himself. He is a conformist–a boy who always goes along with the crowd and does what others tell him to do. Even when fighting back is the right decision, he will walk away and rationalize his choice as the “manlier” thing to do.

But the boy possessed by the Coward cannot even convince himself of his own excuses, and he despises himself for his cowardice. He knows he is a doormat, and as people continue to walk over him, he gets angrier and angrier until he reaches a breaking point and lashes out in full Grandstander Bully fashion. It would have been far better for this boy to handle conflict in a healthier way.

Accessing the Hero Archetype as a Man

I believe the hero archetype is the most difficult for a man to successfully integrate.

On the one hand, teenagers see things as black and white, and despise the wishy-washy convictions and play-it-safe attitude of adults. Teenage Brett would have been disappointed with adult Brett’s decision not to jump off the cliff.

On the other hand, adults shake their heads at the foolish risks young men take and laugh at the unrealistic idealism of young people, telling them they’ll change their mind once they see how the world “really is.”

The complete man must walk the line between these two camps. He must come to understand his own limitations and the true nature of the obstacles in his way; otherwise, he cannot be effective in bringing about real change. At the same time, he cannot lose heart while pushing up against those challenges, and stumble into the kind of cynical apathy that makes seeking greatness seem an impossible task and an entirely worthless endeavor. He needs to be able to sometimes take youthful risks in order to achieve his goals. If a man can pilot his ship through this Charybdis and Scylla, he can become the heroic warrior.

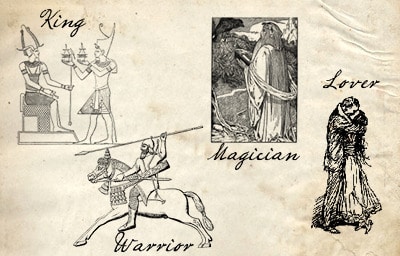

The Four Archetypes of the Mature Masculine:

Introduction

The Boyhood Archetypes – Part I

The Boyhood Archetypes – Part II

The Lover

The Warrior

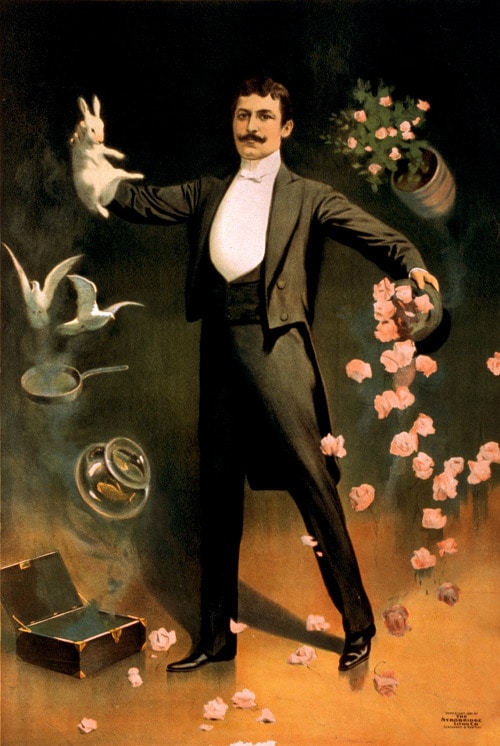

The Magician

The King