Welcome back to our series on the relationship between Christianity and masculinity, which aims to explore the historical and cultural factors that have made women statistically more likely to be committed to the religion than men.

In our last post, we weighed one of the more popular explanations for this gender gap: that the theology, story, and ethos of the Christian gospel was intrinsically feminine from the start, and thus naturally attracts more female than male adherents.

We ultimately dismissed this theory by showing that it’s possible to see both traditionally masculine and traditionally feminine traits in the religion. The fact that the softer, gentler side of Christianity has long been emphasized over its harder qualities, then suggests that factors above and beyond the faith’s intrinsic narrative and theology led to one side being privileged over the other.

Today we will explore theories as to what exactly those “feminizing” factors were, beginning with a discussion of when exactly they may have emerged.

3 Notes Before We Begin

- To trace the feminization of Christianity, this article largely focuses on factors related to church attendance. Obviously, there is an imperfect relationship between religious commitment and church attendance, in that someone may feel committed to their faith, but not attend services regularly. However, a belief in the viability of this disconnect (sometimes referred to as being “spiritual” rather than “religious”) is largely a very recent phenomenon; commitment and church attendance went hand-in-hand for most of Christianity’s history. Additionally, churches are and remain the epicenters from which the faith’s culture, and how it is perceived by society at large, emerges, and church attendance provides the best, most objective data and set of observations — the most viable entry point — with which to examine the more abstract issue of the religion’s overall feminization.

- This article also focuses on the culture of Christianity in the United States, as this provides a concentrated lens through which to explore the subject; Christian churches in nearly all countries have a gender gap, but they’ve all taken slightly different trajectories to arrive there, and it would be impossible to cover each in detail. Nonetheless, much of what is discussed here in regards to American Christianity, will also apply abroad.

- “Feminine” and “masculine” are used in this article to denote those qualities that, on average, tend to cluster most often in females and males, respectively, and have traditionally been associated with each sex. Feminization is not bad, nor masculinity inherently good; every human possesses both masculine and feminine qualities to greater and lesser extents. And Christians would say Jesus too embodied both. The question to be explored then is not why Christianity isn’t wholly masculine, but why a feminine ethos has come to predominate in the religion.

[aesop_chapter title=”When Did the Feminization of Christianity Begin?” bgtype=”img” full=”on” img=”https://content.artofmanliness.com/uploads//2016/08/1-1.jpg” bgcolor=”#888888″]

The simple presence of masculine elements within the Christian gospel is not the only evidence that the faith was not perceived as predominately feminine from its inception. There’s also the fact that the gender gap doesn’t seem to have existed within the religion originally.

Though it goes back much farther than most people realize.

It’s popularly believed that the disparity between men’s and women’s participation in the Christian faith began as a result of the feminist and countercultural movements of the 1960s.

But this isn’t even close to correct.

To find the origins of Christianity’s gender gap, you in fact have to go back not decades, but centuries. Maybe even close to a millennium.

Christianity is a two-thousand-year old religion, and for much of that history we don’t have detailed records and surveys as to the demographics of commitment and church attendance. This makes pinpointing the exact time that the gender gap emerged difficult. But we can assemble a general timeline with a certitude that gets increasing strong in the centuries that approach the modern day.

Having examined the evidence, Catholic scholar Dr. Leon J. Podles believes that men and women were about equally committed to Christianity for the first millennium of its existence. There is, at least, no evidence that a disparity in commitment existed; it was not remarked upon by early church fathers and observers, who would likely have noted the phenomenon, in the same way that, as we’ll see, was common in the religion’s second thousand years.

Podles speculates that the feminization of Christianity began in about the 13th century, for reasons we’ll detail in the next section.

Whether or not the gender gap can be traced back that far, we know with a surety that it began at least as early as the 17th century in America. In fact, the gap seems to have arrived right along with the country’s Puritan settlers. The rolls of early New England churches show more female than male members, despite the fact that there were about 150 men to 100 women in the population overall.

How high was the imbalance in early American church membership? In 1692, famous Puritan minister Cotton Mather shared this firsthand observation on the state of things around the Massachusetts Bay Colony:

“There are far more Godly Women in the World than Godly Men…I have seen it without going a Mile from home, That in a Church of Three or Four Hundred Communicants, there are but a few more than One Hundred Men, all the Rest are Women.”

Mather’s observation of a 4:1 female to male ratio of church attendance is all the more striking when you again consider that the colony had a male/female sex ratio of 3:2. Modern historians have confirmed Mather’s numbers; according to David Stannard, who analyzed church registers in New England, “throughout the colonies, beginning first at the close of the seventeenth and continuing on into the 18th century, the proportion of women to men in church memberships rose to at least two and often as high as three or four, to one.”

Indeed, the story of the 1800s was much the same. In The Church Impotent, Podles cites data from the research of another historian:

“In his study of Congregationalism, Richard D. Shields states that 59 percent of all new members from 1730 to 1769 were women. The figures for southern churches were the same. In 1792, ‘southern women outnumbered southern men in the churches (65 to 35) though men outnumbered women in the general population (51.5 to 48.5).’”

In the 19th century, the gender gap seems to have widened even further.

In 1899, New York-based minister Cortland Myers penned a piece entitled “Why Do Men Not Go to Church?” in which he observed that “Of the membership of the churches nearly three-fourths are women. Of the attendants in most places of worship nine-tenths are women. In one great church I counted two hundred women and ten men.” A survey conducted by The New York Times just a few years later confirmed Myers observation, finding that “69% of Manhattan worshippers were women.”

In a similarly themed piece written nine years previous, “Have We a Religion For Men?” Howard Allen Bridgman inquired into why he and his fellow clergymen’s message “falls upon so few masculine ears” and posed almost word-for-word the same questions we raised ourselves over a hundred years later in the introduction to this series:

“Is the genius of Christianity foreign to the masculine make-up? Have women always outnumbered and outweighed men in the church? Do other religions show a similar disproportion? If the predominance of women be an essentially modern feature of our faith, what causes operated to produce it?”

Bridgman reports the exact sex ratios that Myers did, observing that “three fourths of the Sabbath congregations and nine tenths of the mid-week assembly” were women. He further notes that according to the YMCA, “only one young man in twenty in this country is a church member, and that seventy-five out of every hundred never attend church.”

Declaring that “we must dare to hold the mirror up before the facts” concerning “this disparity of the sexes, as respect to their affection for the Christian faith,” Bridgman admits that “the mainstay of the modern church is its consecrated women,” and that from the outside “the world gets the idea that the church of God is, to a very great extent, an army of women.”

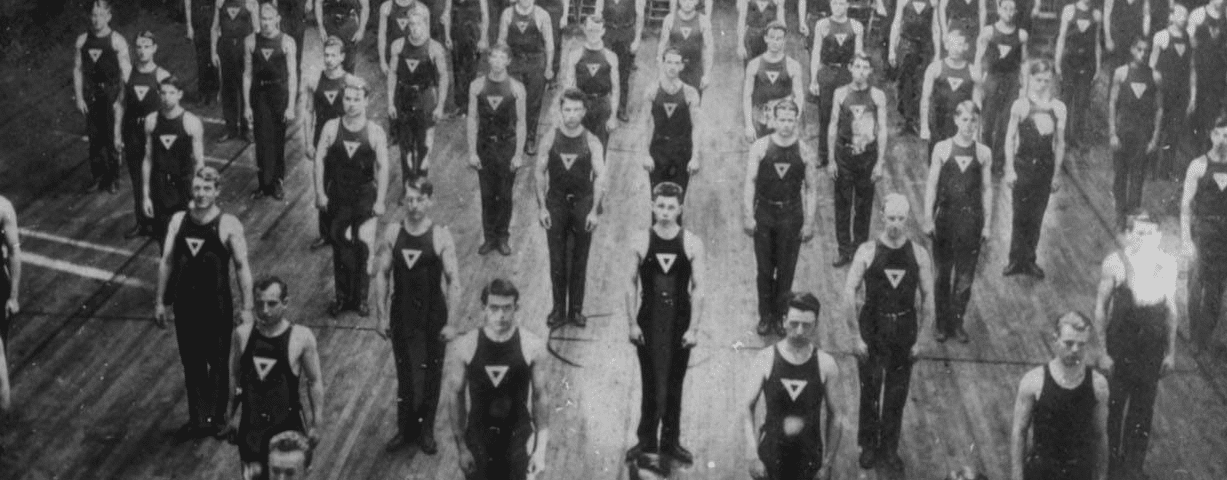

The gender gap persisted into the 20th century, with a survey conducted by the YMCA in 1910 finding that women made up 2/3 of church membership, and the bulk of those who participated and volunteered in congregations as well. By 1929, likely because of the efforts of the “muscular Christianity” movement, which we’ll discuss later in the series, the ratio had shrunk slightly to 59% women and 41% men.

The only time the sex ratio of church attendance was commensurate with the population at large was in the post-war period of the 1950s and 60s, when attending a mainline congregation became part of the fabric of suburban life for men and women alike.

Thereafter it opened back up, and now sits at 61% women/39% men. And therein lies the surprising takeaway: Christianity’s gender gap is actually smaller now than it was a century or two ago.

You might be wondering if the gender gap has to do with men traveling for jobs, or dying in war, or simply not living as long as women, but as it has persisted through times of agriculture and industrialization, from rural life to urbanization, through wartime and peacetime, and in societies where men outnumbered women in the general population, none of those reasons can adequately explain the magnitude of Christianity’s sex ratio disparity.

Beyond all that, one of the easiest ways to know that a “feminization” problem existed prior to the 20th century, lies in the fact that the “muscular Christianity” movement emerged to combat it and make Christianity more masculine in the late 19th. Had there not been a large gender imbalance that couldn’t be chalked up to “normal” demographic factors, such a movement would never have arisen.

Taken altogether, while we can’t pinpoint the exact start of Christianity’s gender gap, we can say with certainty that it has existed for at least several centuries, opening and closing to varying degrees, and perhaps hitting its peak around the turn of the 20th century.

What contributed to the creation of the gap? Let us now at last turn to various theories as to why it emerged, exploring a thesis that its seeds were sown in the High Middle Ages, came to full fruition in the 1800s, and were continuously compounded and entrenched in the 20th and 21st centuries.

[aesop_chapter title=”The Seeds of the Gender Gap ” subtitle=”Bridal Mysticism in the High Middle Ages” bgtype=”img” full=”on” img=”https://content.artofmanliness.com/uploads//2016/08/2-copy.jpg” bgcolor=”#888888″]

Podles points to several factors that emerged in the High Middle Ages that he believes kick-started the feminization of Christianity, the most notable of which is the rise of “bridal mysticism.”

In the New Testament, Jesus is compared to a bridegroom who’s going to come for his bride – his followers. The bride symbolizes the church as a whole.

But in the Middle Ages, female mystics, following the lead of Catholic thinkers like Bernard of Clairvaux, began developing an interpretation of the bridegroom/bride relationship as representing that which existed not only between Christ and the collective church, but Christ and the individual soul. Jesus became not only a global savior, but a personal lover, whose union with believers was described by Christian mystics with erotic imagery. Drawing on the Old Testament’s Song of Songs, but again, using it as an allegory to describe God’s relationship with an individual, rather than with his entire people (as it had traditionally been interpreted), they developed a new way for the Christian to relate to Christ – one marked by intimate longing.

For example, the German nun Margareta Ebna (1291-1351) described Jesus as piercing her “with a swift shot from His spear of love” and exulted in feeling his “wondrous powerful thrusts against my heart,” though she complained that “[s]ometimes I could not endure it when the strong thrusts came against me for they harmed my insides so that I became greatly swollen like a woman great with child.”

The idea of Christian-as-Bride-of-Christ would migrate from Catholicism to Protestantism, and be picked up even by the dour Puritans who journeyed to American shores. Mather himself declared that “Our SAVIOR does Marry Himself unto the Church in general, But He does also Marry Himself to every Individual Believer.” Mather’s fellow Puritan leader, Thomas Hooker, preached that:

“Every true believer . . . is so joined unto the Lord, that he becomes one spirit; as the adulterer and the adultresse is one flesh. . . . That which makes the love of a husband increase toward his wife is this, Hee is satisfied with her breasts at all times, and then hee comes to be ravished with her love . . . so the will chuseth Christ, and it is fully satisfied with him. . . . I say this is a total union, the whole nature of the Saviour, and the whole nature of a believer are knit together; the bond of matrimony knits these two together, . . . we feed upon Christ, and grow upon Christ, and are married to Christ.”

That which was present at the founding of the country, grew to become part and parcel of American Christianity, especially its evangelical strain, and continues to play a significant role in influencing the language and ethos of the faith today.

In Why Men Hate Going to Church, David Murrow points to examples of how the bridal imagery born in the Middle Ages continues into the modern age, citing books with titles like Falling in Love With Jesus: Abandoning Yourself to the Greatest Romance of Your Life, and authors who “vigorously encourage women to imagine Jesus as their personal lover”:

“One tells her readers to ‘develop an affair with the one and only Lover who will truly satisfy your innermost desires: Jesus Christ.’

Another offers this breathless description of God’s love: ‘This Someone entered your world and revealed to you that He is your true Husband. Then He dressed you in a wedding gown whiter than the whitest linen. You felt virginal again. And alive! He kissed you with grace and vowed never to leave you or forsake you. And you longed to go and be with Him.’”

While much of what Murrow calls “Jesus-is-my-boyfriend imagery” is directed at women, Murrow believes it has become suffused throughout the entire faith, and “migrate[d] to men as well.” “These days,” he writes, “it’s fairly common for pastors to describe a devout male as being ‘totally in love with Jesus.’ I’ve heard more than one men’s minister imploring a crowd of guys to fall deeply in love with the Savior.’”

The imagery and language of a romantic, intimate relationship is also very common in modern “praise and worship” songs that have lyrics that are sometimes almost indistinguishable from those that are heard on “secular” radio.

Murrow contends that the idea of individual-believer-as-bride is simply unbiblical, writing that “The Bible never describes our love for God in such erotic terms. The men of Scripture loved God, but they were never desperate for him or in love with him.” Podles believes that the rise of bridal imagery is part of what led men to start abandoning the faith during the late Middle Ages. Both feel that the ethos embodied in the bridal analogy continues to be a factor in why the Christian gospel attracts more women than men.

Podles and Murrow contend that making the goal of the Christian faith to, as the former puts it, develop a “rapturous love affair with Christ” just doesn’t resonate with most men, who struggle to relate to Deity as a blushing virginal bride. The idea of Jesus as committed companion and loving protector is more appealing to women, they say, while men are looking for a leader — a mighty, conquering king to suffer, rather than cuddle, with.

Under this theory, the rise of bridal imagery not only made the Christian narrative less compelling to men, it also pushed the faith’s overall ethos in a more feminine direction. The values associated with brides, especially in centuries past — love, protection, comfort, passivity, obedience, dependence, receptivity – came to dominate the ethos of the Christian gospel, and be privileged over its more masculine qualities of suffering, sacrifice, and conflict.

The rise of a narrative that centered on Jesus as a personal lover, also potentially helped transform the Christian gospel from a public pursuit to a private affair. Men are inherently outward-facing in their disposition – manhood in all cultures and times had to be pursued and proven in the public sphere – but the mysticism of the Middle Ages began to turn the Christian faith in an inward direction.

As Podles puts it, “The transfer of the role of bride from the community to the soul has helped bring about the pious individualism that has dissolved ecclesiastical community in the West.” When “the only real concern of Christianity is ‘Jesus and me’” you get the seeds of the possibility of being “spiritual” rather than “religious”; church attendance becomes more optional, and faith need not inform or intersect with domains like business or politics — all that matters is one’s personal relationship with Christ. Individual salvation is privileged over communal or global salvation; the kingdom of God can wait for the world to come, and needn’t be advanced on earth. Faith becomes transcendence, a matter of feeling and sentiment, rather than action.

If mystic movements in the late Middle Ages made Christianity an increasingly private rather than public faith, cultural and economic shifts in the centuries to come would magnify the idea that the former constituted the realm of women, while the latter was the proper domain of men.

[aesop_chapter title=”The Industrial Revolution ” subtitle=”Religion as the Sphere of Women” bgtype=”img” full=”on” img=”https://content.artofmanliness.com/uploads//2016/08/3-copy.jpg” bgcolor=”#888888″]

If the seeds of Christianity’s feminization were planted in the Middle Ages, those seeds came to full fruition in the 19th century. The fertilizer? The Industrial Revolution.

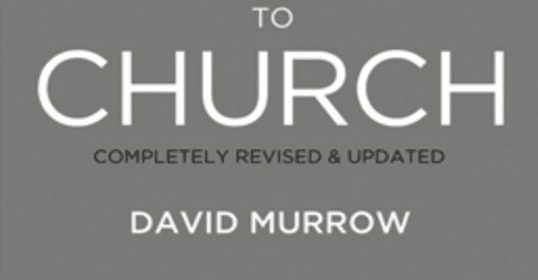

In agrarian societies, men and women worked together within the household economy – their labors and their lives greatly overlapped.

With the rise of industrialization, they began to move in increasingly separate spheres. Men went off to work in factories and emerging white collar jobs; women stayed home to tend to home and hearth. Of course, some women (and children) took jobs in the new industrial economy as well, but these were largely single women; in 1890, only 4.5% of all married women were “gainfully employed.”

A new value system emerged to explain and encourage this new economic structure. Called the “cult of domesticity” or the “cult of true womanhood” it posited that a woman’s greatest role was that of wife and mother, that her highest virtues centered on piety, purity, domesticity, and submissiveness, and that she was responsible for being “the light of the home.” While her disposition and abilities were seen as unfit for participation in the reason-demanding, rough ‘n’ tumble public sphere of commerce and government, her inherent purity and aptitude for nurturing gave her the equally important responsibility of acting as the guardian of virtue. Women were to teach their children moral principles, and cleanse their husbands of the dirt and grime – both literal and metaphorical – they accumulated in the arenas of work and politics.

As piety began to be associated more and more exclusively with women’s sphere of life, the proportion of female to male churchgoers naturally became increasing lopsided. Religiosity came to be seen as more of a feminine thing, in contrast to masculine endeavors of the public sphere. In order to spend more time on business, men could outsource their family’s faith, sort to speak, leaving to their wives the responsibility for nurturing it in their home and in their children. Men could venture into worldly pursuits, and rely on women to draw them back to the hearth and upwards to heaven with their personal piety.

With women making up as much as ¾ of congregations, ministers naturally began to play to their core audience, and a symbiotic relationship between women and their clergymen developed. Denied power and influence in the public sphere, women developed it within the church. The more women showed up, the more pastors created programs and positions for them and praised and tailored their messages and services to the “fairer sex”; men were base, broken creatures while women were angels — the preservers of faith and morality. Services came to resemble, as historian Ann Douglas puts it, “a sort of weekly Mother’s Day.”

The more feminine services became, the more men stayed away; and the more women outnumbered men in the congregation, the more ministers catered to their needs. And on the cycle went, compounding the feminization of Christianity that had begun centuries prior and continues into the modern day.

[aesop_chapter title=”Christianity’s Feminization Cycle ” subtitle=”Compounding Effects From the 19th Century to Today” bgtype=”img” full=”on” img=”https://content.artofmanliness.com/uploads//2016/08/jesus-1.jpg” bgcolor=”#888888″]

As the demographics of churches became lopsided towards women, and the ethos of church culture, and in turn the culture of Christianity as a whole, shifted towards the feminine, this further convinced men to stay away, creating a cycle of feminization that began in the late Middle Ages, and which produced effects that intensified during the 19th century and continue into the modern day.

Let’s take a look at what those effects were:

Lack of Masculine Pastors/Leaders

Ministers in the 19th century had a reputation for being sensitive, milquetoast mama’s boy types, who’d be more comfortable sipping tea with ladies than playing a game of rugby, and this reputation was not entirely unwarranted. As pastors spent the bulk of their time tending to their flock, and their flock was up to 75% women, these clergymen did not travel much in masculine circles. As one minister put it, a pastor “has sometimes spent the forenoons with his books, and his afternoons with the women and children of the parish in his pastoral work, with no adequate provision for personal contacts with the men of his community.”

This again became a compounding cycle, in which more feminine men felt more comfortable and were a better fit for pastoring a church, and enrolled in seminaries in greater numbers, while more masculine men felt that the pulpit wasn’t a place for fellows like themselves and sought other professions. As 19th century minister Thomas Wentworth Higginson explained, these dual tracks were encouraged even as boys were growing up:

“One of the most potent causes of the ill-concealed alienation between the clergy and the people, in our community, is the supposed deficiency, on the part of the former, of a vigorous, manly life. It must be confessed that our saints suffer greatly from this moral and physical anhaemia, this bloodlessness, which separates them, more effectually than a cloister, from the strong life of the age. What satirists upon religion are those parents who say of their pallid, puny, sedentary, lifeless, joyless little offspring, ‘He is born for a minister,’ while the ruddy, the brave, and the strong are as promptly assigned to a secular career!”

Beyond the subjective evaluation of a lack of virility amongst clergymen, there have also been objective measurements of such. Studies have shown that modern ministers have, on average, less testosterone than men in other careers. And according to personality tests cited by Murrow, “men entering the ordained ministry exhibit more ‘feminine’ personality characteristics than men in the population at large.” And of course, the ranks of the ministry are increasingly filled not by men who are more womanly, but by women, period.

While Christians of the past two centuries have complained of a lack of virility in their pastors, there’s also been a statistically certified lack of other kinds of male mentors in the church as well. For example, a survey done in 1920 found that 73% of Sunday School teachers were women, and still today women are around 56% more likely than men to participate in Sunday school and to hold a leadership position in a church (not including the role of pastor).

Does a lack of masculine role models at church negatively affect the recruitment and retention of masculine members? Edwin Starbuck, a prominent psychologist in the early 1900s thought so, positing that “the boy is a hero-worshipper, and his hero can not be found in a Sunday school which is manned by women.” Murrow agrees, citing the research of Dr. Michael Lindsay, who found that:

“the number one reason high-achieving men don’t go to church is they don’t respect the pastor. Those men who did go to church often chose a megachurch because they saw the pastor as their leadership peer. ‘Respecting the senior pastor is vital to predicting whether a man is actively involved,’ Lindsay says.”

“Men respect pastors who are properly masculine,” Murrow opines. “They are drawn to men who, like Jesus, embody both lion and lamb. They find macho men and sissies equally repulsive.”

Statistically speaking, those denominations which have opened doors to female clergy widest and earliest, are struggling more than those which have retained male-only clergy and leaderships boards. Murrow points out that “The ‘100 Largest and Fastest Growing Churches in America,’ compiled by Outreach magazine, all have a man at the helm,” and Podles cites the Church of England as an example of the effect of the pulpit’s feminization on the demographics of church membership:

“In 1994, the church welcomed its first female priests. Ten years later, the church ordained more women than men—a first for any denominational group. Over the same period, the female-male church attendance ratio went from 55–45 to 63–37.8 The Church of England is quickly becoming a church of women, by women, and for women.”

Podles further predicts that “The Protestant clergy will be a characteristically female occupation, like nursing, within a generation.”

Softer Theology/Messaging

“In today’s church, the gospel is no longer about saving the world against impossible odds. It’s about finding a happy relationship with a wonderful man.” –David Murrow

Research has shown that women are more likely to imagine God as characterized by love, forgiveness, and comfort, while men picture him in terms of power, planning, and control. With more women than men belonging to Christian churches, it’s not surprising that the religion’s theology, and the messages heard from the pulpit, have come to emphasize the former qualities over the latter.

Podles argues that men think in terms of dichotomies and conflicts — in or out, black or white. They tend to be more orthodoxic and privilege rules over relationships. Women (and more feminine men) tend do the opposite, and wish to overcome differences and assuage conflict, for the sake of greater acceptance and peaceable relationships.

Consequently, modern sermons tend to deemphasize the contrast between heaven and hell, sin and life, grace and justice, sheep and goats. There are less martial analogies, fewer calls for Christians to take up their cross and become soldiers for Christ. There is less emphasis on the need to suffer, struggle, and sacrifice for the gospel and for others, and more emphasis on how the gospel can be a tool towards greater self-realization and personal fulfillment. The gospel is presented not as heroic challenge, but therapy – the way to “your best life now.” The focus is on rewards over obstacles. All gain, no pain.

These changes in emphasis led one 19th century YMCA speaker to declare that the Christian gospel had become “too easy and too cheap,” where what men really longed for was the promise of “battles instead of feasts, swords instead of prizes, campaigns instead of comforts.”

Murrow observes that the modern tenor of the gospel turns the faith’s original message on its head: Whereas Jesus “promise[s] suffering, trial, and pain…today’s Christianity is marketed…[as] the antidote to suffering, trial, and pain.”

Indicative of these changes, Murrow says, is the way “the kingdom of God” has fallen into disuse in describing the church, in favor of the “family of God.” In the former, the ethos is more mission directed; in the latter it’s more’s relational. Each member of the “family of God” has a relationship with each other, and with Jesus Christ. And not just any kind of relationship with the savior — a “personal relationship” — a term whose popularity Murrow thinks contributes to the gospel’s lack of appeal to men:

“It’s almost impossible to attend an evangelical worship service these days without hearing this phrase [personal relationship with Jesus Christ] spoken at least once. Curious. While a number of Bible passages imply a relationship between God and man, the term ‘personal relationship with Jesus’ never appears in the Scriptures. Nor are individuals commanded to ‘enter into a relationship with God.’

Yet, despite its extrabiblical roots, personal relationship with Jesus Christ has become the number one term evangelicals use to describe the Christian walk. Why? Because it frames the gospel in terms of a woman’s deepest desire—a personal relationship with a man who loves her unconditionally. It’s imagery that delights women—and baffles men.

…

When Christ called disciples, he did not say, ‘Come, have a personal relationship with me.’ No, he simply said, ‘Follow me.’ Hear the difference? Follow me suggests a mission. A goal. But a personal relationship with Jesus suggests we’re headed to Starbucks for some couple time.”

One might think a softer, less strenuous and divisive message would be appealing to both men and women alike, and indeed the former will say they want a church that’s not judgmental or constricting. But as Murrow reports in his book, what men say they want is frequently at odds with how they vote with their feet, as “The National Congregations Study found that self-described liberal churches were 14 percent more likely to have a gender gap than conservative ones.” Even when they don’t know it, Murrow says, men “long for a harsh affection—the love of a coach who yells at his players to get every ounce of effort; the love of a drill sergeant who pushes his recruits to the limits of human endurance; the love of a teacher who demands the impossible from his students. As Western society feminizes, it’s getting harder for men to find this kind of love.”

Sentimental/Romantic Music

Victorian women like Harriet Beecher Stowe described the Christian religion as “comfortable,” “poetical,” “pretty,” “sweet,” and “dear,” and these qualities were reflected in the music 19th century churches used in their services. Here and there could be found a masculine tune like the martial “Onward Christian Soldiers,” but hymns tended most often to the feminine and sentimental — praising motherhood and domestic bliss, musing on the sorrow of death, and concentrating on the world to come rather than the here and now. In 1915, Charles H. Richards, the composer of many hymns himself, noted the overuse of “songs of vague and dreamy sentimentality” and “plaintive and melancholy songs, which imply that the harps are still to be hung upon the willows in a strange land.”

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries “praise and worship” music replaced hymns in many Christian churches. But while Murrow sees some good in this type of music, overall he thinks “P&W” may have even less appeal to men than the hymns of old, and “has harmed men’s worship more than it has helped”:

“the evidence seems to indicate that, while P&W is very appealing to some men, it’s a turnoff for many more. Before P&W, Christians sang hymns about God. But P&W songs are mostly sung to God. The difference may seem subtle, yet it completely changes how worshippers relate to the Almighty. P&W introduced a familiarity and intimacy with God that’s absent in many hymns.

With hymns, God is out there. He’s big. Powerful. Dangerous. He’s a leader.

With P&W, God is at my side. He’s close. Intimate. Safe. He’s a lover.

Most people assume this shift to greater intimacy in worship has been a good thing. On many levels, it has been. But it ignores a deep need in men.”

That need, Murrow says, is to reverence a God that’s “wholly other.”

Instead, men are to relate primarily to God as a lover, and Murrow observes that the kind of language used in praise and worship songs – “Your love is extravagant/Your friendship, it is intimate/ I feel I’m moving to the rhythm of Your grace/Your fragrance is intoxicating in this secret place” – “force[s] a man to express his affection to God using words he would never, ever, ever say to another guy. Even a guy he loves. Even a guy named Jesus.”

Since many men don’t find the language of praise songs very compelling or natural to mouth, those that attend churches with P&W music have stopped participating in one of the major components of worship services, ceasing to sing at all. Indeed, if you look around at the audience of a typical megachurch, most men are simply silently watching the praise band rock it out.

Feminine Aesthetics

The music and messages of church services were not the only things that became feminized over the last couple centuries. So did the overall atmosphere and aesthetic of Christian congregations, as well as the art of Christian culture as well.

A frilly, Victorian design sense took over churches in the 19th century, and still characterizes more traditional churches today. Murrow describes this aesthetic to a T:

“Quilted banners and silk flower arrangements adorn church lobbies. More quilts, banners, and ribbons cover the sanctuary walls, complemented with fresh flowers on the altar, a lace doily on the Communion table, and boxes of Kleenex under every pew. And don’t forget the framed Thomas Kinkade prints, pastel carpets, and paisley furniture.”

The industrial, mall/movie theater-like design of modern megachurches is an intentional attempt to throw off this staid, foo-fooey aesthetic, in favor of an atmosphere that, if not distinctly masculine, comes off as more gender neutral.

The artwork that adorns churches, as well as church materials, took a turn for the feminine during the 19th century as well. In 1925, author Bruce Barton wrote that the way popular culture typically presented Jesus was as “a frail man, undermuscled, with a soft face—a woman’s face covered by a beard—and a benign but baffled look, as though the problems of living were so grievous that death would be a welcome release.” Other critics of popular images of Christ argued that the weak, pallid, ethereal Jesus seen in many paintings bore little resemblance to the nomadic, rugged, whip-cracking carpenter depicted in the scriptures.

Still today, the most popular images of Jesus typically show him holding a lamb, surrounded by children, or talking to women. One rarely sees Jesus depicted as hanging out with men (unless it’s “The Last Supper”), overturning tables, or calling Pharisees vipers.

Lack of Risk & Innovation

Men, on average, are more inclined to take risks than women. This may be why the gender gap didn’t exist during the first centuries of Christianity’s history; before the faith became an established religion – the status quo – it was something revolutionary and even dangerous, requiring enormous sacrifice, even of one’s own life. Everything about being a Christian was being developed and tried out for the first time; everything had to be innovated from scratch.

But as Christianity became the dominant religion in many countries and cultures, it naturally lost its rebellious, risky ethos. It became more risky for one’s status and position in society not to be Christian and conform to a culture’s dominant norms. This increasing entrenchment may have ultimately made the religion less compelling for men.

The same thing that happened to the faith on a macro level, also occurs on a church by church basis. Murrow has found that men often outnumber women when a church is first “planted,” as starting something new requires the kind of risky, enterprising, action-taking men find satisfying. Uncertainty must be confidently navigated; innovation is welcome and encouraged.

Then, as the church becomes more settled, it also become more safe and predictable. Norms and traditions become more hardened, and practices become less open to change, challenge, and experimentation. The church becomes more institutionalized.

New ideas are met with much resistance, weighed on a scale rigged in favor of keeping the status quo, and debated with an eye towards avoiding contention and hurt feelings.

In such an environment, men may feel useless and frustrated. They want to employ their propensity for risk-taking and the abilities they’ve honed in their careers in improving their church; they want to help make things more efficient and effective. But as a Baptist minister explained in 1906, “Men do not find enough to do in the church of that which requires skill and courage. There is too great a contrast between the strenuous business life to which they are accustomed and the lifeless committee work upon petty things to which they are invited.”

Men express the same frustration today, telling Murrow that they “couldn’t stand the inefficiency of church meetings” and describing “local congregations as ‘unproductive’ and ‘focused on the wrong things.’” In churches where masculine strengths aren’t welcome and utilized, and are even seen as a threat to the status quo, men will simply decide to invest their valuable time and energy into other “worldly” pursuits instead.

Murrow muses that men’s bold, results-driven mindset may be why new, popular megachurches have less of a problem with a sex ratio disparity than older, more traditional churches. These large churches are innovative, willing to experiment, and have a clear mission and purpose; they give off “a buzz of success about them that men find attractive” and a palpable sense of “energy, forward movement, purpose, and drive”:

“Men see their values emphasized in big churches. These congregations speak the language of risk, productivity, and growth. They become known in the community. Big churches measure effectiveness, celebrate achievement, and are constantly launching new projects and initiatives to capture men’s hearts.”

While megachurches may be getting men to show up to their entertaining, hour-long services (which are actually often called “experiences”), Murrow observes that they seem to be participating to a lesser extent than who attend mainline churches, so that the megachurch model, while it has in some ways disrupted the feminization cycle and closed the gender gap in attendance, hasn’t solved the sex disparity in regards to commitment.

Emphasis on Emotion and Verbal Expression

For centuries now, church services of all kinds have largely revolved around the same set of components: sitting, standing, reading, listening, sharing, praying, and singing. Nowadays, many churches have done away with any standing, and as mentioned above, singing has frequently become spectating. So the church experience, from the Sunday service to the Sunday school, essentially involves only talking, reading, and listening.

The music and messages are designed to elicit emotion, and emotional utterances are not only supposed to be received, but also given in return; a good Christian should openly share what’s on his or her heart in order to stir the hearts of their fellow believers.

All the “action” of the faith thus happens internally, while the body remains inert. Spirituality is sedentary.

This kind of expressive, yet passive experience can be dull for both sexes, but may be less favorable to men who tend to be more kinetic, and more easily bored. It’s therefore harder for boys and men to be, as Murrow puts it, “good at church.” Consider a boy in Sunday school:

“The rules favor children who can sit quietly, read aloud, memorize verses, and look up passages in books. A star pupil is also compliant, empathetic, and sensitive. A long attention span and the ability to receive verbal input from a female teacher also help.”

With this kind of set-up, Murrow argues, “it’s very hard for boys to win.”

As is stated in a Biola Magazine article, because of the feminization of Christian worship, “many people think of church only as a nurturing place that addresses personal needs…Think: sitting in circles, sharing feelings, holding hands, singing softly, comforting members.”

[aesop_chapter title=”Conclusion” bgtype=”img” full=”on” img=”https://content.artofmanliness.com/uploads//2016/08/5_conclusion-copy.jpg” bgcolor=”#888888″]

Christianity’s feminization cycle was set in motion during the Middle Ages with the rise of bridal mysticism, picked up speed in the late 19th century because of the separation of male and female spheres and the association of religion with the latter, and continues to turn into the new millennium.

When women began to attend church in greater numbers than men, pastors began tailoring their messages and services to them. Men felt even less useful, welcome, and needed, and remained MIA. As a result, modern churches continue to focus the ethos of their culture and the cream of their attention on their most faithful demographic, with many more activities, ministries, and resources devoted to women and their children, than to men.

As most pastors and congregants alike have a limited view of the full history of Christianity’s gender gap, and the fact that it hasn’t always existed and can both widen and narrow, they believe the situation has always existed and cannot be altered. Ex post facto reasoning is used to explain it; women outnumber men in churches, ergo women are simply more inherently spiritual than men and are the religiously superior sex.

Women are thus taken to be the model for what spirituality should look like; if women participate more in Christianity because they’re more spiritual, and their spirituality is manifested in emotional, verbal, and relational ways, then that is spirituality. If men then fail to match this model — aren’t emotional about their faith, don’t cry out of the depths of their conviction, or aren’t comfortable sharing their feelings — it’s not because there are other ways to embody faith, but because they’re spiritually deficient, and aren’t trying hard enough to humble themselves and get their souls right before God.

The men who do fit into the system are those, as Murrow puts it, “who know how to function in an environment dominated by feminine gifts and values. Men who are verbal, studious, musical, and sensitive rise to the top. They get the ‘stage time,’ while average Joes who lack these soft virtues either leave the church or become passive pew sitters.” When men who don’t fit in critique the system as unwelcoming to their type of masculinity, those that do feel at home in the Christian church sometimes blame them, saying the problem is not the church, but that these men are stuck in an overly macho stereotype of what manliness is and are letting false ideas of masculinity become an obstacle to their salvation. Since the insiders don’t have a problem fitting in, they thus wonder why other men can’t get with the program.

Since it works for them, neither the women nor the men who happily attend Christian churches have the motivation to change the current system. And so the gender gap persists.

This theory of the origin and persistence of the gender gap, it should be noted, is just a theory. There are others. To another explanation, and the movement it engendered that attempted to turn back the feminization of Christianity, is where we’ll turn in the last piece in this series.

Read the Series

Christianity’s Manhood Problem: An Introduction

Is Christianity an Inherently Feminine Religion?

The Feminization of Christianity

When Christianity Was Muscular

[aesop_chapter title=”Sources” bgtype=”color” full=”on” img=”https://content.artofmanliness.com/uploads//2016/08/5_conclusion-copy.jpg” bgcolor=”#888888″]

The Church Impotent By Leon J. Podles

Why Met Hate Going to Church by David Murrow

Muscular Christianity by Clifford Putney