When the CDC reported a few months ago that suicide rates had risen over the last two decades in nearly every state in the U.S. — going up by a third in half of them — there was much discussion around literal and digital kitchen tables as to what exactly was behind such morbid statistics. Some posited that what we’re seeing is the result of a kind of existential crisis haunting our society.

The most common hypotheses forwarded as to what is causing this crisis are: 1) the decline of religion, 2) a lack of community, and 3) the scarcity of truly purposeful work.

All of these factors make for highly compelling, sensible narratives, and all have undoubtedly greatly contributed to modernity’s crisis of meaning.

Yet I have just one issue with assigning them full explanatory power: they don’t fit with my own personal experience.

I am religious — practicing a faith that gives me thorough, salient answers to the great questions of life. The church I belong to very much meets the definition of a true community, I have an extraordinarily happy family life, and I’ve got a decent group of friends — I can check the box for those bonds and face-to-face contacts so frequently touted as being vital for psychological health. So too, my work couldn’t be more satisfying and purposeful — I hear directly from people who share the tangible ways AoM’s content has improved and even outright changed their lives.

I should thus be the very model of living a meaningful life . . . and yet, I still experience great pangs of existential angst from time to time. I’m not talking about depression, or even unhappiness. Existential ennui can lead to depression and/or suicide, but it can also paradoxically co-exist with real happiness; indeed, the very fact of the latter can sharpen the intensity of the former: “I’m plenty happy . . . so why do I still feel this niggle of discontent?”

Existential angst can be found in the specter of questions like “What’s the meaning of this?” “What’s the point of it all?” “What’s it all about, man?” It’s the feeling of being a stranger in a strange land. Of feeling out of place, almost out of body. Of wondering what’s real in a world that can feel curiously fake.

If the decline of religion, community, and purpose doesn’t wholly explain these restive murmurings, then what does?

We have a few hypotheses which we’ll lay out below, and as visual metaphors can be the best prompts for grasping an idea, we’ve complemented the theories with symbolic illustrations as well.

Sources of Existential Angst

Porous Communities & Lifestyles

The reason that modern communities, rich with common values, traditions, and practices, aren’t a panacea to existential angst, is that they’re not hermetically sealed. They’re porous.

You may feel committed to the culture shared within your community, but you are never not aware that it isn’t shared with the millions of people outside of it. There are other options, other alternatives, other principles and beliefs to build your life around. Where there are choices, there is FOMO. Are you sure you’ve picked the right one?

When it comes to the decision of whether or not to belong to a religious community, we find ourselves in a “pluralized, pressurized moment,” writes James K.A. Smith, “where believers are beset by doubt and doubters, every once in a while, find themselves tempted by belief.”

Because the believer and non-believer alike inhabit porous communities, through which the fragrance of other modes of life and systems of beliefs continually waft, each group is constantly subjected to “cross-pressures.”

The religious are surrounded by peers who have no need for faith and the constrictions that come with belief, forcing them to wonder if these “heathens” really seem any less happy for having built their lives around projects of personal significance, rather than God. “Even as faith endures in our secular age,” Smith writes, “believing doesn’t come easy. Faith is fraught by an inescapable sense of its contestability. We don’t believe instead of doubting; we believe while doubting.”

The non-believing experience cross-currents as well. Even the committed atheist who lives a life of great secular significance can experience the occasional longing for a bit more transcendence. He may intellectually acknowledge some of the consolations of faith, without seeing any possibility of changing his mind in order to experience them. As a biographer said of a period of Ernest Hemingway’s unbelief, “he missed the ghostly comforts of institutionalized religion as a man who is cold and wet misses the consolations of good whiskey.”

Cross-pressures don’t just arise from the tension between faith and non-belief, of course. Social media exposes us, in full, stylized, living color, to every other lifestyle option as well. Should you do that workout or this one? Adopt this diet or that one? Live here or there? Be an entrepreneur or an employee? Settle down or stay single? No matter which path we choose, we’re confronted with signs beckoning towards a different way.

We are haunted by possibilities; by the question of whether we’re living life right, and whether other people are living it better. The grass is always greener on the other side, and in the modern age, we are surrounded in every direction by seemingly lush pasture.

Anomie & Weightlessness

At the turn of the 20th century, French sociologist Emile Durkheim did an exhaustive survey to try to figure out what factors most influenced a country’s rate of suicide. What he discovered was that this statistic was most impacted by the presence in society of something he called anomie.

Anomie, which literally means “without law” in German and French, was defined by Durkheim as a state of “normlessness” — the absence of shared rules, standards, values, etc. It’s a concept that well describes the landscape of modern society; for though one’s personal community may share a unified culture, the wider society shares little common code.

While the most serious consequence of a lack of shared norms may be suicide, it also afflicts the living with a pervasive sense of restlessness and emptiness.

There are two reasons for this.

Norms provide a kind of gravitational force that can keep you grounded. Personal freedom without any such guideposts, standards, or expectations feels like being adrift in deep space. The weightlessness is sometimes exhilarating, but you lack any frame of reference for where you are: up and down, left and right are meaningless.

As an existential astronaut, you are charged with the task of creating your own rules, values, and expectations — your own personal meaning for the world. Yet lending these self-created standards sufficient credence to let them guide your life — knowing their only source of authority is your own inclinations — is an insanely difficult task.

The absence of norms not only eliminates a set pattern to build your life around, it also eliminates a barrier to push against.

The norm-filled society not only provides existential meaning to those who conform to these shared expectations, it also provides meaning to those who reject them. There is great significance to be found in the friction of pushing back on society’s standards — in tweaking expectations, being unique, forming a secret, subversive underground culture, fighting “the man.”

Today, however, there is little mainstream culture to rebel against. There are still a few lingering expectations, but “live and let live” generally reigns. You can get married at 20 or 40 or never, live with someone for decades and never get hitched, have 9 kids or none, within wedlock or out, wear what you want without anyone batting an eye, date someone from a different race, get a tattoo on any part of your body, marry a lady, or a dude, be a corporate warrior or a stay-at-home dad. You can pretty much do whatever you want, short of breaking the law, and endure minimal social repercussions.

Nobody cares what you do.

And, of course, the flip side of that is, nobody cares what you do.

Molehills Into Mountains

This current period of modernity not only provides little “friction” in the form of social norms, but in the form of real existential challenges as well.

For the most part, life is peaceful and comfortable in the West. We’re not embroiled in a world war. Poverty still exists, but is not the grinding variety of even a century past. Many diseases have been eradicated. Crime is down. Technology has made it easier to connect than ever before, and provided tons of conveniences. As Stephen Pinker argues, the modern age has “has brought improvements in every measure of human flourishing.”

In this state of peace and prosperity, in which many big problems have been solved, we have the “luxury” to concentrate on smaller issues. And so you get a culture which picks apart people’s words to excise an offensive phrase, and guards vigilantly against microaggressions.

Even when engaging in problems that are smaller than a world war, but still constitute serious societal ills, a gap exists between how significant we want the fight to feel, and how significant it does feel. That is, we yearn to participate in some kind of epic quest, but ultimately find the underpinnings of our pursuits too flimsy to support the full weight of our longings. The stakes aren’t high enough to furnish the meaning we crave.

As a result, we try to gin up those stakes ourselves — distorting the contemporary landscape into something more threatening, more dangerous — more compelling — than it is. Hence you get the current popularity of dystopian books and films — fiction that supposedly hews uncomfortably close to our current reality — and the belief that we’re living through an unprecedented time of tumult — even though an objective survey of the past reveals periods that were just as, and often more, chaotic and troubled. For there is a perverse pleasure in believing one is living through the worst of times — it may be troubled, sure, but it is historic. To be living through a significant time seems to make one significant by association.

Yet this illusion still doesn’t generate sufficiently enduring meaning; like a distortion seen in a funhouse mirror, it distracts and entertains, but for a moment.

Morbid Self-Consciousness

“All the world’s a stage,” Shakespeare said centuries ago, and people have been aware since time immemorial that they are being watched by others.

But never before has that stage been so pervasive, nor its backdrop so readily managed.

It’s hard to remember now, but there was a time, in very recent memory, in which you saw only a relatively small slice of the lives of people in your social circle; outside of when you saw them at work, or at a get-together, their personal lives were something of a black box.

You never saw the vacation pictures of your co-workers, your acquaintances, your extended family. A very good friend might have showed you a slide show of them two generations ago, and a package of prints a generation ago. But not always; even among close friends you might have seen no visual evidence of their trips at all. Likewise, you never saw pictures of them at the end of a 5k or out with their kids or on an anniversary dinner with their spouse. A picture of mom and dad at the hospital with their newborn? Only the figures in the photo itself ever laid eyes on it.

Yes, it’s hard to remember now, but these snapshots of life’s highlights were tucked inside a personal photo album, and seen only by a handful of one’s closest intimates. They therefore had no reason to be posed and perfected (and of course you didn’t even know how they’d turn out until you got the prints back from the developer weeks and even months later).

Today, a very different story. One’s “personal photo album” is open to hundreds of onlookers via social media. There is more pressure to “perform” — to edit the “film” of one’s life to show only the best, most envy-inducing highlights. A mother has to primp and prep, shortly after giving birth, to prepare for the requisite newborn-in-arms, mom-in-hospital-bed shot she’ll share on Instagram.

Even if you don’t post such “best of” snapshots yourself, viewing those of others inevitably shifts the paradigm through which you see yourself. You can’t help but wonder how your own life measures up. You can’t help but think more about how it looks to an outside observer. More and more we see ourselves from outside ourselves. We become hyper aware of whether or not our life seems sufficiently cool, adventurous, and exciting to others. We develop what those at the turn of the 20th century (a time quite like our own), called “morbid self-consciousness.”

A Dismal Reflection in the Mirror

For most of human history, media of all kinds was controlled by “elite” gatekeepers. If you wanted to print a publicly consumed opinion, you had to score a position at a newspaper. If you wanted to be heard on radio or television, you had to be hired on a show. If you wanted to publish a book, you had to land a deal with a publishing house.

These channels weren’t always democratic, but they did ensure that media was somewhat vetted. “Trash” has most certainly been broadcast in all ages, but for the most part, filters ensured that what was seen, read, and heard was issued by those who had earned the privilege — through education, practice, experience — to disseminate their thoughts.

As a result, the contents of the public sphere gave one a fairly inspiring view of what human beings are capable of; even if you didn’t agree with someone’s positions, they were articulate, intelligent reminders of human potential.

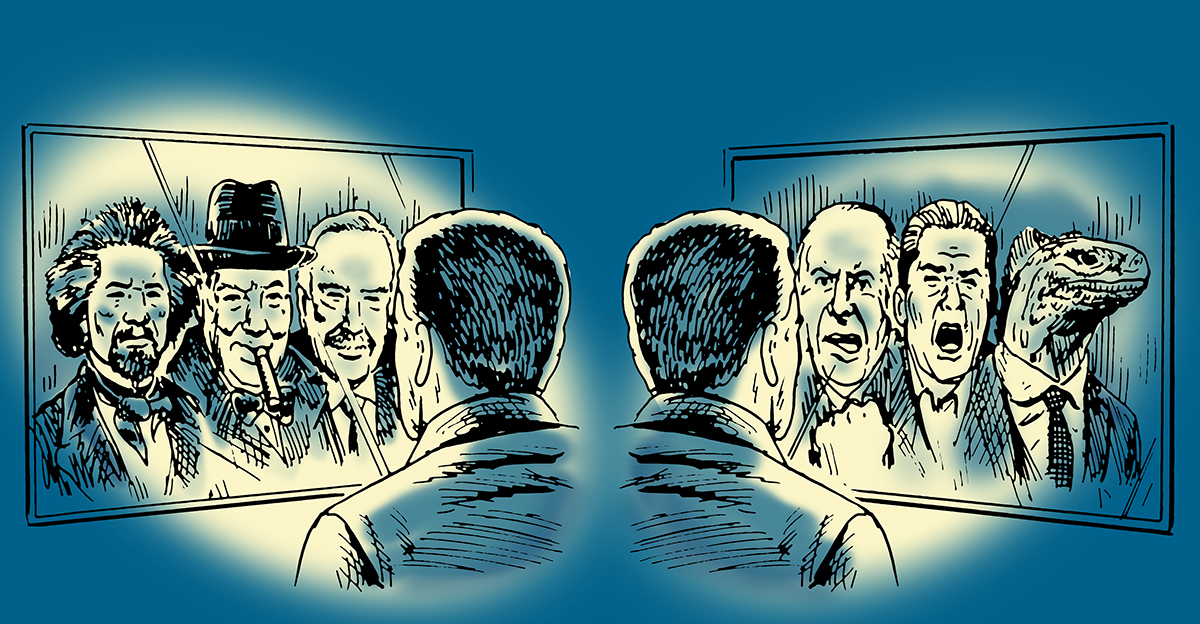

The mirror held up to society showed a flattering image of humankind. Such that Shakespeare could proclaim:

“What a piece of work is man! How noble in reason! How infinite in faculties! In form and moving, how express and admirable. In action, how like an angel! In apprehension, how like a god!”

And the British statesman William Gladstone could assert:

“Man himself is the crowning wonder of creation; the study of his nature the noblest study the world affords.”

And the minister Theodore Parker could say:

“Man is the highest product of his own history. The discoverer finds nothing so grand or tall as himself, nothing so valuable to him. The greatest star is at the small end of the telescope, the star that is looking, not looked after nor looked at.”

The digital age has removed any barrier to entry when it comes to making one’s voice heard. Consequently, we are surrounded by a jarring cacophony of comments, feedback, and opinions — little of which has been vetted, researched, or thoughtfully considered prior to being released. Instead it is the product of emotional responses and knee-jerk reactions. It is the product of our id, rather than our ego.

The current reflection of man in our societal mirror isn’t a pretty picture; it is instead an image from which we instinctively recoil. Rather than showing the heights to which he may soar, it shows the depths to which he can descend. Here is man at his most base and impulsive; here is man possessed of a reptilian brain.

“What a piece of work is man!” we still feel prompted to say. But we mean it in a very different sense.

A Deluge of Information, Without a Lever for Action

Another result of living in a filter-less world of media, is that the drip of information that used to dribble out of gatekeeper-managed faucets, has now become an unbridled deluge.

There has been, as we noted, a great surge of information on possible lifestyles — on where to travel, where to live, and every potential occupation. There are endless lists of pros and cons on this form of exercise, and that kind of diet. There are exhaustive arguments and counterarguments available for every set of beliefs.

There has been almost no accompanying uptick, however, in “levers” with which to take action on this information. You can find endless resources on endless options, but little that tells you how to choose among them. You can find seemingly infinite tips and hacks for how to improve your life, but far less on how to successfully put them into practice.

Indeed, while the availability of information has exponentially exploded, the problem of implementation — a problem of basic human nature — has remained stubbornly the same. There’s all this information, but it isn’t any easier than it’s always been to take action on it. Out of this mismatch between thought and action, grows FOMO and a terrible sense of restlessness.

Living With Existential Angst

None of the proposed sources of existential angst outlined above are wholly ill in nature; the factors that have given rise to them are in fact a mixture of the good and the bad. And they just are. Positive, negative, they have made answering the great existential questions — Who am I? Where am I going? Why am I here? — more difficult.

And so we have the great paradox of modern life in the West in which our quality of life is up, but our subjective well-being is down. Life is safer, healthier, easier — and yet depression, anxiety, and suicide are on the rise.

This seeming contradiction becomes less puzzling, however, once you realize people want more than comfort and convenience — they want lives of meaning and significance, qualities which have arguably become more elusive in our age.

So what to do?

Well, while I do not think things like religion, community, and purpose (professional and otherwise) hold the entire answer, they do act as a strong hedge against the full force of modernity’s existential emptiness. While the shield they form is not impenetrable against the corrosive effects of ennui, they are effective at blocking a broad spectrum of its “rays.” These existential building blocks still feel the most like something, in a world that often feels like nothing.

It helps too to engage in challenges, which, even if they don’t ultimately fulfill our desire for a truly heroic quest, nonetheless create a healthy kind of friction and resistance in our lives — a ballast in a landscape of weightlessness. It’s better to take action on anything than to be paralyzed into inertia by everything. (Shout out to our Strenuous Life program, which provides both a suggested direction, and a lever to actually take action on it.)

No matter what you do, there’s no mitigating all existential angst, though. And while it sometimes pushes people to quit this life altogether, what can seem like a dread-inducing problem, can also be viewed as a vitalizing challenge; the desire to know if you’re living right, to figure out who you are, and where you’re going, and what it’s all about, man, can really be considered one of the great privileges of being alive.