Ulysses S. Grant is a historical figure who’s often portrayed in a not-so-flattering light. Many Americans know him as a drunk, inept businessman who found himself thrust into generalship during the Civil War and led the Union to victory not because of his military genius, but simply because he happened to be on the side that had more men and weapons. The story then goes that Grant parlayed his military success into a career in politics where he led a failed presidential administration mired in corruption, and later died penniless.

That’s the story you often hear about Grant. But my guest today argues that this common portrayal doesn’t come close to capturing the complexity of this American leader. In fact, if you look at Grant more closely, you can find a shining example of courage, resilience, and quiet dignity.

My guest’s name is Ron Chernow, and he’s the author of several seminal, bestselling biographies, including ones on Alexander Hamilton, George Washington, and John D. Rockefeller. In his latest biography, Grant, he’s trained his lens on the life of Ulysses S. Grant. Ron and I begin our discussion talking about Grant’s upbringing and how it influenced his unflappable, yet passive personality. We then discuss the real extent of Grant’s alcoholism, how it hurt him throughout his career, and how he managed it throughout his life. Ron then explains how someone who had such a passive and tender personality developed an aggressive new military strategy that would serve as a template for modern warfare. From there we look at the lessons that can be learned from the way Grant handled Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House.

We then discuss Grant’s presidency, including whether Grant was to blame for the corruption in his administration and the oft-overlooked successes he had while president. We end our conversation with the argument that Grant’s quiet, dignified professionalism is a much needed example in today’s flashy and overly self-promotional world.

Show Highlights

- How does Chernow decide who to spend years researching and writing about?

- Why does Grant get overlooked as a president and a general?

- How did Grant come by his famously cool temperament?

- How the “S” of Ulysses S. Grant came about

- What was Grant like as a West Point cadet?

- Grant’s role in the Mexican-American War

- How Grant managed personal political differences with his family and friends

- Grant’s forays in the business world

- The truth about Grant’s drinking

- What did Grant do differently from other Union general?

- How Grant introduced modern warfare

- How Robert E. Lee and the South responded to Grant

- Did Grant really want to be president after the Civil War?

- The corruption in Grant’s White House

- What successes did Grant have as president?

- Where Grant ranks among “best presidents” lists

- Grant’s life after the presidency

- Why Grant decided to write his memoirs

- What remains compelling about Grant in our modern age?

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- Ron Chernow’s books

- The Lesson Grant Learned About Fear in the Civil War

- 43 Books About War Every Man Should Read

- The Mexican-American War

- The Best Presidents in History, Ranked

- Be Your Own Tyrant: Rockefeller’s Keys to Success (based largely on Chernow’s biography)

- The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant

Grant was an absolute pleasure to read. The narrative ability of Chernow shines throughout this biography. You learn so much about an important time in American history, yet you feel like you’re reading an engaging story. I highly recommend picking up a copy.

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

ZipRecruiter. Find the best job candidates by posting your job on over 100+ of the top job recruitment sites with just a click at ZipRecruiter. Get your first posting free by visiting ZipRecruiter.com/manliness.

Barbell Logic Online Coaching. For the past two years, I’ve worked with Starting Strength Coach Matt Reynolds in my barbell training. In those two years, I’ve gained 40lbs of muscle while taking an inch off of my waist and I’ve hit PRs that I never thought I’d hit at my age. If you want to get stronger and healthier, get started with Barbell Logic Online Coaching. Go to aom.is/startingstrength and use code AOMPODCAST at checkout to save $50 on your registration.

Health IQ. Health IQ uses science and data to secure lower rates on life insurance for health-conscious people. To see if you qualify, get your free quote today at healthiq.com/MANLINESS or mention the promo code MANLINESS when you talk to an agent.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Recorded with ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. Before we get started we’re going to a little soliloquy here, so bear with me. Yesterday January 3rd, marked the 10 year anniversary of when I started theartofmanliness.com. The very first article I published was How To Shave Like Your Grandpa, which is about safety razor shaving. I know that’s how a lot of you discovered this site. Didn’t think this was going to be my full-time job. I was a second year law student, 25 years old. I thought I’d be an oil and gas attorney, but here we are, 10 years later, been a wild and crazy ride. Since then, we’ve published some books based off the site, started the podcast, which has grown into this thing I never imagined it would grow into.

A lot of people to thank to get where we are today. First my wife, my partner in crime in this thing. Kate, thank you with the editing, the writing, just taking care of the administrative tasks. Also, Jeremy Andeberg, our managing editor, jack of all trades, podcast producer. And all the other people who have contributed to The Art of Manliness either via content or helping with the back end stuff, thank to all of you guys. Also, thank you, our audience, our readers, podcast listeners, thanks to you guys who’ve been with us since the very beginning. I know a lot of you, in fact I interact with you. Thank you for sticking with us. Thanks for all you who joined us along the way. You’ve got a million choices, places to check and get content, or read things, so it means a lot to us that you’ve decided that we’re one of those options, one of those things you do. Also, thanks for the letters of support you’ve given us over the years, and encouragement. It really means a lot. Thank you, and here’s to 10 more.

Let’s get started with today’s show because it’s a good one I’m excited about. Ulysses S. Grant is a historical figure who’s often portrayed in a not so flattering light. Many Americans know him as a drunk, and a businessman who found himself thrust into generalship during the Civil War, and led the Union to victory not because of his military genius, but simply because he happened to be on the side that had more men and more weapons. The story then goes that Grant parlayed his military success into a career in politics where he led a failed presidential administration mired in corruption and later died penniless. That’s the story you often hear about Grant. But my guest today argues that this common portrayal doesn’t come close to capturing the complexity of this American leader. In fact, if you look at Grant more closely, you can find a shining example of courage, resilience and quiet dignity.

My guest’s name is Ron Chernow, and he’s the author of several Seminole best-selling biographies including ones on Alexander Hamilton, that’s the one that that musical everyone’s talking about is based on, George Washington, and John D. Rockefeller. In his latest biography, he’s trained his lens on the life of Ulysses S. Grant. Ron and I began our discussion talking about Grant’s upbringing and how it influences unflappable, yet passive personality. We then discussed the real extent of Grant’s alcoholism and how it hurt him throughout his career, and how he managed throughout his life. Ron then explains how someone who had such a passive and tender personality developed an aggressive new military strategy that would serve as a template for modern warfare.

From there, we look at the lessons that can be learned from the way Grant handled Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse and reconstruction. We then discussed Grant’s presidency including whether Grant was to blame for the corruption in his administration, and the oft overlooked successes he had while president. We end our conversation with the argument that Grant’s quiet and dignified professionalism is a much needed example in today’s flashy and overly self-promotional world. Really great show. After the show’s over, check out the show notes at aom.is/grant.

Alright, Ron Chernow, welcome to the show.

Ron Chernow: It’s a pleasure to be here with you, Brett.

Brett McKay: You have written some of the most influential biographies in the 20th and 21st Century. Of course there’s Hamilton, which was adapted into the hit Broadway musical, biography about Washington, John D. Rockefeller, and your latest is about General Ulysses S. Grant. My first question’s a two parter. First, generally how you decide which figures you’re going to spend, I imagine years, researching and writing about.

Ron Chernow: I’ll spend about five or six years per book. I always say that for a biographer, there’s no more important question than the choice of subject because if you choose the wrong person, nothing can go right. If you choose the right person, nothing can go wrong. It’s gets a little bit like marriage in that respect. I think that I’ve been very, very lucky in the people that I’ve chosen. One of the things that I look for, I’m looking for more than just telling an interesting yarn, although I hope the person has had a fascinating life. I’ve kind of been looking for the people whom I felt were creating basic building blocks of American politics, and business, and society, and where I felt that their story was also the perfect vehicle for telling the story of an entire period of American history. This is a history lesson for the readers, but I hope that it’s so entertaining that they don’t notice that as they’re absorbing all of this information.

Brett McKay: Why Grant this time?

Ron Chernow: Well Grant, you know, I’d always had a fantasy about doing a big sweeping dramatic saga of the Civil War and reconstruction. Grant is the figure who really unites those two periods. Had Abraham Lincoln lived, he would’ve been the figure. But Grant is right in the center of everything happening in both the Civil War and reconstruction. I felt that while Americans tend to know a lot about the Civil War and sometimes in extraordinary detail, but it knew little or nothing about reconstruction. If you know everything about the Civil War and nothing about reconstruction, you have, as it were, walked out in the middle of the drama because the North wins the war militarily, but one could probably argue that the South then wins the war politically afterwards. Grant was a very, very important figure in terms of giving me that lens through which to look at all of these events.

Brett McKay: Well, and despite being such a central figure in both the Civil War and reconstruction, Grant often gets overlooked as a President, and even sometimes a military commander. A lot of the praise is given to some of the southern because, “Oh, they were the best at West Point,” like General Lee. Why do you think that is?

Ron Chernow: Well, one thing I should’ve mentioned in terms of how I choose subjects is I have a contrarian streak in my nature, so I love nothing more than to take a figure whom I feel has been forgotten, or neglected, or misunderstood in some way. I did this with Hamilton. People forget now that the musical is such a sensation. When I started working on Hamilton in 1998, people had forgotten who he was. He was fading into obscurity. I felt that with Grant, Grant had been one of the major Americans of the second half of the 19th Century, probably second only to Lincoln. You just have to look at the size of Grant’s tomb, which is largest mausoleum in North America, to realize how important he was considered at the time.

How did that get lost over the years? I think what happened after the Civil War, the South badly battered and defeated an attempt to restore its pride. A school of thought of historians and Confederate generals and politicians started called The Lost Cause, which really began in many ways, to rewrite the story of the Civil War. Instead of the Civil War being caused by slavery, they said the war had been caused by state’s rights. They really kind of wrapped the Confederacy in a rather romantic aura so that Robert E. Lee was considered not only the great general, but a perfect and Aristocratic figure as well. As part of that glorification of Lee, there was a corresponding denigration of Grant.

Then what happens after the Civil War when Grant is … after all it was during his two terms as President, he’s the President overseeing reconstruction, which much of the white south hated. They really had a vest interest in running down his presidency, which did have a lot of scandals. That was not an invention of southern historians at all. But I tried to show in the book that the scandals, while they happened and they were important, were not nearly as important as other things that happened in Grant’s presidency that had been forgotten such as his successful campaign to crush the Ku Klux Klan, which I think was one of the most farsighted and courageous actions undertaken by any American president. It was huge.

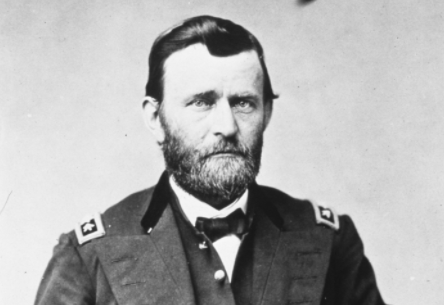

Brett McKay: Let’s get into Grant himself because after reading this book, I fell in love with Grant. He was just an interesting character, has his demons that he fought, but I think that made him stronger in the process. Grant was known throughout his life for his unflappable, cool temperament. Was that something he had to consciously develop, or was that just his genetics and due to his upbringing?

Ron Chernow: It’s a very good question because he grows up in southwestern corner of Ohio in a very strict Methodist household. He has these two completely dissimilar parents. His father, Jesse, was a kind of arrogant, pushing, thrusting kind of character. His mother, Hannah, was very prim and quiet and pious. Grant clearly seems to imitate his mother in that respect. Whether that was genetic, or whether that was an identification with her, it’s hard to say. I wish that we could put Ulysses on the couch, but we can’t.

One thing that we know both from his behavior as a child and his behavior as a adult, is that he had an aversion to the kind of bragging in which his father engaged. If there was a genetic component to this modesty, it was certainly something that was reinforced by his constantly reacting against his father who was always pushing him forward. Ulysses was always pushing back, and develops almost a kind of what we would call passive aggressive personality as a child. I think it also created that stubbornness that he became known for. You see that in terms of his resisting his father rather stubbornly throughout his childhood.

Brett McKay: That sort of passiveness, that’s how he got his name, Ulysses S. Grant.

Ron Chernow: Yes, that kind of says it all because he was born Hiram Ulysses Grant, which saddled him with the very unfortunate initials of HUG, or hug. Well, you can imagine the merciless teasing from the other boys. So he dropped the Hiram and he became Ulysses Grant. Then what happened, his father decided that he was going to go to West Point. Ulysses didn’t decide that he was going, his father decided for him and Ulysses went reluctantly. When the local congressman nominated Grant for the academy, he made a mistake and sent him the name as Ulysses S. Grant. That bureaucratic era stuck and Grant in later years would when asked what the S stood for, would tell people it stood for absolutely nothing. It kind of was a statement about him that has a symbolic quality that this name that we know him by was something imposed on him rather than something that he had fully chosen.

Brett McKay: Another paradox with Grant was, he was unflappable, cool, almost fearless. We’ll talk about in the war, like bombs would be going off by him, he just would ignore it. But at the same time, he had this aversion towards just death. Even when he ate food, the meat had to be charred to a charcoal briquette.

Ron Chernow: Yeah, that’s absolutely right. What happened when he was growing up in this small town in southwest Ohio, his father was a tanner. In the main town of his boyhood, Georgetown, the tannery was directly across the street from the two-story house. The fumes from the tannery would waft into Ulysses’ second floor bedroom and he found it revolting. There was nothing that he hated more than working in the tannery, not only because of the odors, there would be rats running around. It was a very vile atmosphere. This left him with a permanent squeamishness so that for the rest of his life he could never eat meat swimming in its own blood or juices. Every meat would have to be burnt to a crisp. He said he could never eat the flesh of anything that walked on two legs. He was extraordinarily finicky about food. Those were childhood aversions that he never overcame. Kind of funny for a man who was derided as this filthy butcher, that he was really so squeamish.

Brett McKay: That’s interesting. Let’s talk about Grant. He goes to West Point. What was he like as a cadet at West Point?

Ron Chernow: Well, it’s often said that he was a disaster. He was really, I would say, lackluster. He graduated in the middle of his class, 21 in a class of 39. He didn’t distinguish himself in terms of tactics or artillery or anything like that. His best subject was math. In fact, it’s very funny that his highest ambition when he graduated from the academy was to be an assistant math professor there, not a full math professor, an assistant math professor. That was the height of his ambition. But one quality that really stood out to me when I was examining his years at West Point was that the other cadets respected his quiet judgment. People would come to him to arbitrate disputes.

That’s kind of where I began to see the military leader. The person who is the calm center of the storm, someone who’s known for his fairness, for almost a kind of judicial temperament, and you see the way that the other cadets respected him. There’s certain boys who are respected because they’re very charismatic, or others because they’re great athletes, or very dynamic. That was not the case with Grant. It was sort of these quieter virtues that people picked up on. That really anticipates the way that his men reacted to him. There was no flash and strut about Grant as a general. It was just quiet competence and people respected his sense of honesty, and his sense of fairness.

Brett McKay: After he graduated from West Point, he went to go serve in the Mexican American War. What was his position there? What did he do?

Ron Chernow: That experience is … for four years he’s down in Texas, Louisiana, and then Mexico during the Mexican War. It was extremely important to his training as a general because he was the Quarter Master. Let me say a couple things about being the Quarter Master. The Quarter Master is the person, in other words, who’s coming up with all the provisions and the supplies. This is perfect training because he becomes a master of logistics, of moving supplies to the troops. When it comes to the Civil War, he’s going to be overseeing armies across a 1,500 mile area. The movement of troops and materiel, and the mastery of supplies is going to be a very important component to his success as a general. That’s one thing.

The other thing that I loved researching when he’s actually in the Mexican War itself was that as the Quarter Master, he was not obligated to be in any combat, that if he had a position behind the lines, which if he’d chosen to take it he could’ve avoided any danger. But he voluntarily chose to be in combat in every single battle. This is true bravery. There were moments that he did things that were extraordinarily daring. At one point they were low on ammunition and he got on horseback in this town and he rode along the side of the horse, his body slung on the side of the horse. The horse was kind of dashing across these intersections where it’s being fired at by the Mexicans. Grant almost kind of like a rodeo rider, is on the far side of the horse, sort of grabbing onto the top of the saddle.

I think it shows his bravery, and it also develops this nuts and bolts knowledge of the way that an army works. Grant was really someone who knew the Army from the top to the bottom.

Brett McKay: Did he have any interactions with any of the Confederate soldiers? How did that help him later on during the War?

Ron Chernow: It was absolutely important because what’s interesting for anyone who’s read about the Civil War, you read about the Mexican War, and it’s the same cast of characters. The same cast of characters both Union and Confederate generals, they all had their first military experience in the Mexican War. The only difference being the chief generals are people like Winfield Scott and Zachary Taylor who were … Well not Winfield Scott, was involved at the very beginning of the Civil War but not for long. But the people who would be the significant Union and Confederate generals in the Mexican War, their rank of Captain Major. Grant gets to know Robert E. Lee. Lee was already major, so Lee was a little bit older and higher up, and already doing very, very impressive things.

I think that that experience was absolutely crucial for Grant because he had a superb memory. He had an inventory of all of these generals who would later face him. During the war he would repeatedly make reference to having known these Confederate Generals during the Mexican War, and that he knew their strengths and weaknesses. There were quite a number of battles where his sense, particularly in certain cases, his sense of the perceived incompetence of Confederate Generals made him more sure of himself and certainly more aggressive. It was a very important experience.

Brett McKay: What I was struck by Grant was, people often complain about, “Oh, this year at Thanksgiving,” everyone was like, “Don’t talk about politics at Thanksgiving.” Grant, his best friend, his best man at his wedding was General Longstreet. His father was an ardent Democrat, which at the time they were pro-slavery. How did Grant manage those divisions, those schisms, politically in his personal life?

Ron Chernow: That’s a very good question because Grant is fighting long before the firing on Fort Sumpter. Grant is fighting his own private Civil War. He’s born into an abolitionist, strongly abolitionist family in Ohio. He marries into a slave owning family in Missouri. He’s caught in the crossfire between on the one hand, this overbearing abolitionist father and this no less overbearing slave owning father-in-law. Grant by his own admission did not start out as a raving abolitionist. After all, he did marry into a slave owning family. But I think that it gave Grant an understanding of the culture of both North and South. I think that one can plausibly argue that his behavior at Appomattox Courthouse where when Lee surrenders, Grant is very magnanimous, that he was someone who understood the psychology of the South as well as the North. It may have come from the fact that in his personal life, he had for many years, by the time of the war, had straddled that North/South, free labor/slave labor divide, so in a way he was the perfect person for that moment.

Brett McKay: So Grant had a … it wasn’t lackluster, but just nothing outstanding about his military career in the Mexican War. After the Mexican War, he becomes a civilian and tries to put his hand in business, but that didn’t go very well for him.

Ron Chernow: Yeah. Firstly, he still is in the regular Army. He’s posted through a series of frontier garrisons where he’s kind of lonely and depressed. He starts drinking. He can’t be with his wife and children because he can’t afford it. He’s drummed out of the Army in 1854 in a drinking episode, and then he returns to St. Louis. He and his wife Julia own property that they had received as a wedding gift from Colonel Dent, Grant’s slave owning father-in-law. Grant really tries to make a go of it at farming, but fails and not for lack of hard work. He’s reduced by, around 1857, he’s reduced to selling firewood on street corners in St. Louis when one of his old Army buddies runs into him and Grant looks all disheveled and depressed. He’s aghast and he says, “Grant, what are you doing?” Grant says, “I’m trying to settle the problem of poverty.” That Christmas Grant has to pawn his watch in order to buy gifts for his family. He’s really hitting bottom at that point. Grant was never, never lucky in business before the war.

Brett McKay: Yeah, well he wasn’t lucky afterwards either and we’ll talk about that.

Ron Chernow: Exactly, yeah, yeah.

Brett McKay: You brought up his alcoholism. That’s something he’s known for, that he was just a drunk. What was his relationship with alcohol really like? Were the rumors overblown or did he really have a problem with alcohol?

Ron Chernow: A number of recent biographies, admiring biographies of Grant have argued, “Oh, the reputation for drinking is all overblown and those were stories invented by malicious rival generals during the war.” I found, and I researched this in great detail, that Grant was a genuine alcoholic. He had all the earmarks of an alcoholic. By his own admission, he couldn’t take just one drink. It became then the second, the third, and the fourth. Also, by everyone’s description, even a single glass of alcohol he would begin to slur his words and stumble about. He would undergo this personality change from a very repressed character to a very jovial character.

I think that the reason there’s been so much confusion on this issue, is I discovered that Grant had a definite pattern of drinking. He was a periodic drinker. He was a binge drinker. He could go for even two or three months without touching a drop of alcohol, only to have a two or three day bender. When I discovered he never drank on the eve of a battle, certainly never drank during battle, but he had enough control over the problem that after a big battle, when the tension was off, he would then make a side trip to another town where his soldiers could not see him, and then he would indulge. According to Sherman, he could come back smelling fresh as a rose from this.

There were a lot of people who worked very, very closely with him who in all honesty said, “I never say him touch a drop of liquor.” I discovered why, because he had enough control that they did not see him in these episodes.

Brett McKay: It might’ve been like a psychological release. The guy was super buttoned up, right?

Ron Chernow: Very buttoned, yeah. It was a combination of someone … you’re absolutely right … someone who on the one hand was very tightly buttoned up and on the other hand is carrying unbearable pressure. It’s more than a figure of speech to say that Grant was carrying the weight of the nation on his shoulders, particularly the other Union generals. So many of them proved incompetent that it was all up to Grant. Before Lincoln brought Grant east in March 1864, in the eastern, in the Virginia theater of the war Grant had been preceded by five or six miserable failures as generals. He was facing tremendous pressure. Remember, these Civil War battles were gigantic and blood, could be as many as 100,000-150,000 men going into battle. The casualties could run up into the thousands, or even tens of thousands in certain cases.

Grant said later in the war, because people were impressed during battle, he would fire off these orders, but Grant after the war talked about the fact that he knew that every order he gave was going to, however successful it was, was going to lead to the deaths of hundreds or thousands of men, and how inwardly paralyzing that could feel. I can completely understand why someone with his drinking history, or even someone not with his drinking history would crave the release of that tension periodically.

Brett McKay: As you mentioned, when the Civil War started, the Union, they were actually having a hard time against the Confederacy despite out-manning and out-arming them. What did Grant do different from the generals that were in charge at the beginning that allowed him to start having these victories?

Ron Chernow: Yeah, it’s a very, very good question because I think that … First of all because of Grant’s pre-war failures. I think that he becomes very early in the war, Colonel and a Brigadier General. Within 10 or 12 months, he’s Major General. I think that Grant, because of his pre-war failure, he has nothing to lose and everything to gain in this war just from a personal standpoint. He shows speed, flexibility, daring. He is aggressive, and he’s confident in his aggression. Let me just give you a few things that William Tecumseh Sherman said about Grant. Of course Sherman was Grant’s Chief Commander and knew him best. He talked about Grant’s simple faith in success.

He said, “I can liken it to nothing other than a Christian’s faith in the Savior.” Grant always believed that he was going to win and that this gave him confidence, and gave him the confidence to be aggressive. Sherman also said that it gave him the confidence. There was always a moment in every battle, he said, where the outcome seemed to be hanging in the balance where the commander on either side, who had the confidence to take the offensive would win, and Grant was always that person. Sherman said that Grant seemed to know. He used the word, “Divine the hour,” when to strike back at the enemy.

You would think that this might be a trait common to generals. It was not. There were many generals, particularly in the Union army in the east, they were whining, they were procrastinating. They just wanted to drill and train and equip their army, but not lead them into battle. They always felt that the more training they had, the better they were going to be. Grant had a very different attitude because Grant realized that every day, every week that went by of his training his own armies, that the enemy was simultaneously strengthening their armies. The delay did not necessarily work in your favor. You’re not the only one who was reinforcing your army.

There are a lot of different things. I think also, we get into a different kind of discussion in terms of when Grant becomes General In Chief in March 1864. There, I think the answer is a few things. Number one, he decides that all of the various Union armies have been operating in separate theaters of war independently of each other. He decides that he’s going to coordinate them and simultaneously launch armies over a 1,500 mile area. He’s really supervising four distinct armies at the same time. You can do that, couldn’t have been done in any previous war, you could do that because of the telegraph and the railroad.

Again, very, very important his master of logistics goes back to what we were talking about before about Grant as Quarter Master. Sherman said, who contrasting Lee and Grant, Sherman said Lee would attack the front porch, Grant would attack the bedroom and the kitchen. I’m not sure what Sherman meant about the bedroom, but I know what he meant about the kitchen, which they would cut off your food supply so that when he has, during the last year of the war, he has Lee pinned down in Richmond, and Petersburg, and Virginia. Lee’s army is being fed by five railroads and one canal. Grant systematically cuts off all five of the railroads and the canal, starving Lee out, and then Lee is finally forced to give up Richmond and Petersburg and he flees out to Appomattox Courthouse where Grant and Sheridan had all surround Lee’s army and captured, and effectively end the war.

Brett McKay: There’s a lot of ways Grant introduced modern warfare that we see today.

Ron Chernow: Absolutely, modern warfare, yeah. He’s exploiting the technology of warfare. Interestingly enough, by the time he became General In Chief in 1864, a lot of Grant’s conclusions had become Lincoln’s conclusions as well. The North had a superiority in manpower and manufacturing, but it would only really work if there was simultaneous attacks along the very long front. What had been happening before that, since the South had a smaller population, was that if one place was attacked by Union army, the Confederate army would then rush all these reinforcements there. There was another attack, then they would rush the reinforcements there.

But Grant realizes that if you attack both of those places simultaneously, neither can reinforce the other, then suddenly the South would begin to feel the weakness that it had in terms of population and manufacturing ability. He was a very great strategist, and I think the image of him just as a butcher and he threw tens of thousands of young men against the enemy. It doesn’t hold up because if you look at Virginia, going back to Irvin McDowell and George McClellan, there had been Joe Hooker, Ambrose Burnside, George Gordon Meade. Who am I leaving out? John pope. They had the same advantage in terms of northern population manufacturing. They had not been able to defeat the Confederate army or Lee in Virginia.

It was Grant was able to do that. Something more was going on than simple northern superiority, and manpower, and materiel.

Brett McKay: You mentioned earlier Grant was magnanimous when Lee surrendered. It was unconditional, but he still allowed Lee and the Confederate soldiers to maintain some dignity and honor in the process. How did Lee and the South in general respond to Grant’s magnanimity?

Ron Chernow: Very positively. Grant allowed the Confederate soldiers to keep their horses and mules. He allowed the officers to keep their firearms. The Confederate army was really starving at that point. He issued 25,000 rations. Most importantly he did not allow his men to gloat, or even celebrate any way. He refused to enter Richmond after the fall of Richmond, even though it was the capital of the Confederacy. Said to his wife, Julia, he said, “Defeat is bitter enough for these people without my throwing it in their face.” He was really very, very high minded. He became, at least briefly heroic in the South for his generosity because he had been bogeyman of the South before then. Then people saw how gracious he could be in victory.

It didn’t last long, not because of Grant, but because of the situation that developed in the South as blacks were given citizenship, and under the 13th Amendment, equal rights into the 14th, and then voting rights under the 15th, which then provoke a very violent backlash in the whites.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about his presidency. Did he really want to be president, or was this another instance of Grant passively being carried into something against his will?

Ron Chernow: I think it was a little bit of both. I think that Grant was always more ambitious than he cared to admit. After all, Sherman was constantly warning him, Sherman thought the ways of Washington were evil and was always warning Grant not to go to Washington, not to be drawn into the political world. This was something that Grant did willingly. I think he also realized that his political attractiveness was greater if he seemed to be the bashful, modest hero, which had large element of reality to it. Grant is sort of swept along, but Grant has a way of being there to be swept along in a way that shows he is very much in sympathy with what is happening with him. He was the great hero of the war, so he occupied this special place. I think that’s something that he wanted. This happens with all presidents once in office, they got a taste of the power, they get accustomed to being in the White House, and they’re all very reluctant to give it up.

Brett McKay: What was his leadership style as President? Did he try to carry over that military style leadership, or was he able to adapt?

Ron Chernow: Yes interesting story, particularly since we have a President who also had never been elected to office before, although Grant had much more experience in the ways of Washington because he’d been General In Chief. He was General In Chief in the War Department in Washington after the war for a year. He was even acting Secretary of War for a time, so he wasn’t as much of a stranger as what, say Trump is to the White House. But still, he made a lot of mistakes by his own admission because his style during the war as commander had been very, very secretive. It has been kind of intuitive and impulsive. What he doesn’t do at first, to his later regret, he doesn’t really consult people enough, he doesn’t vet his appointees, he makes a lot of mistakes in terms of appointing people.

But I think that there was a learning curve. He certainly does better as time goes on. I think that one clear weakness of his presidency is in the appointment area, although there were some really outstanding people whom he picked, Hamilton Fish, who served all eight years as Secretary of State is, I think, one of the really great Secretary of States in American history. Amos Akerman, who is his Attorney General, and from Georgia and brings 3,000 indictments against the Ku Klux Klan and crushes the Klan in the South. There were other examples of really major achievements by his appointees.

It was not as sometimes caricatured that this was just completely crony ridden administration, although there was an element of that. But as I was saying earlier, it’s not the whole story of his presidency. As a result, in 1948, a historian in Virginia did a poll of American presidential historians and they ranked Grant second from the bottom. They said that only Warren Harding of the early 1920s was worse. The most recent poll, Grant has risen to number 22, which puts him exactly at the midway point. I think that it’s going to rise. I don’t think that he’s a great president of the caliber of a Washington or a Lincoln, but I just think that he’s a major president, even despite the flaws in his administration.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about some of his successes as President. We talked about the corruption. I think you make a good point in the book that if there was another person besides Grant, there probably would’ve been corruption anyways because it was the gilded age, government had expanded, et cetera.

Ron Chernow: Yeah, it was a corrupt era, and also there had been enormous expansion of the federal government because of the war. There were numberless opportunities for grab, and god knows people took advantage of it. There’d been a lot of corruption in the previous administration of Andrew Johnson. There’d been a lot of corruption under Abraham Lincoln as well. The federal government greatly expanded after the war, an enormous amount of corruption going on in Washington, and also in state and local level. Grant, rightly or wrongly becomes associated with that. I’d say wrongly to the extent that Grant himself was not personally corrupt. He never condoned the corruption. In fact, he quite vigorously prosecuted the corruption most of the cases. As happens when something is on your watch, you get stuck with it.

There is one case, this so-called Whiskey Ring investigation where whiskey brewers were cheating the government on revenues they owed. One of the Confederates of this conspiracy was a man named Orville Babcock who’d worked for Grant for 14 years, who was effectively his Chief of Staff. Grant just completely blind, to how unscrupulous this guy is to the point where … a major mistake, Grant offers to sit for a deposition in Babcock’s behalf. It’s taken and Babcock is acquitted. That’s kind of the place where Grant clearly crosses the line.

But even there, he ended up bringing … the administration brought 350 indictments against the Whiskey Ring. Grant would prosecute. In fact, he had said early in that investigation, he made this famous statement that no guilty man escape. Grant’s record with scandals is not a great one, but there are some redeeming features there.

Brett McKay: What do you think his successes are? What do you think people should know about his presidency?

Ron Chernow: Well, I think that in terms of the issues lingering from the Civil War, there are successes. He feels the successes of the war are preservation of the Union, abolition of slavery. I think his great achievement is that he feels a personal responsibility for safeguarding the four million African Americans who’d been enslaved, who are now not only free but are full fledged American citizens. Thousands of them were murdered in the south by the Klan. Grant crushes the Klan. I think that’s the great achievement of his administration.

But there are others less known. There’s a major, major dispute with England that could easily have led to war over something called the Alabama Claim. The Alabama was a ship during the Civil War, outfitted in Union shipyards, and it had preyed on Union shipping throughout the war. After the war, the federal government wants major compensation from the British government for the raids. Instead of going to war over the issue, Grant and his Secretary of State, Hamilton Fish, pioneering something that’s brand new. They submitted to International Arbitration. Not only does the United States get a lot of money in the International Arbitration, war is avoided and they have established a new mode of dealing with international conflict. Kind of a major achievement.

Grant takes really the first halting steps, he should’ve gone farther, but he takes the first halting steps towards civil service reform. Makes major effort to clean up corruption on the Indian reservations, although the whole story of what happens to Native Americans during Grant’s administration is not a pretty one at the end, even though Grant’s intentions were very good. Major, major achievement that I was really amazed at, Grant appoints hundreds and hundreds of blacks to public office, including we have a black ambassador to Haiti and to Liberia, first black diplomats. Even though he, from the war had a reputation of being anti-Sematic, he appoints probably more Jews to public office than all the other 19th Century presidents combined.

Even his first commissioner of Indian affairs, Eli Parker, is a full blooded Seneca Sachem Indian. We talk about diversity now, Grant seems to have been almost the one who invented it. In fact, Fredrick Douglas, who was a regular visitor to the White House, said during the 1872 election, said Grant had been the “firm, wise, vigilant, and partial protector of my race,” and he counted in one department alone Grant had appointed 250 blacks to office. His appointment record was really outstanding in terms of groups that had been excluded from federal jobs before.

Brett McKay: What was Grant’s life like after the presidency? Still stoic and cool as ever, or did he become more expressive? What did he do in his later years?

Ron Chernow: Well, he did. He did something very, very interesting. He always had wanderlust, and so he did an around the world trip that lasted for two years and four months. He met with every head of state, every King, Queen, Emperor, President, Prime Minister, you name it, Grant met them. He really pioneers a brand new role for the post-presidency because he is meeting with these heads of states, and he’s having serious political discussions. He begins to engage in a certain freelance to his diplomacy actually, arbitrates an offshore island dispute between Japan and China. No ex president had ever done anything like that. We’re much more accustomed today, of ex presidents going to the Middle East to monitor elections or things like that.

When Grant was doing these things, it was completely unheard of. Grant had always been very, very shy about public speaking. His typical speech was like a 60 second speech. He would get up and make some jokes how he couldn’t give a speech, and then sit down. Well, he suddenly, his first stop on the tours in England, and Liverpool, Manchester, and other places, 100-200,000 people turn out. Grant suddenly is forced to make speeches, and turns out he’s a very good speaker, like everything he put his mind to. He ended up doing it well and enjoying it more.

The around the world trip was a great triumph for him, and it was widely reported in the press what was going on. Americans felt very proud as he went around the world meeting these heads of state. His reputation keeps rising during the trip to the point when he returns to the United States, he decides that he’s going to make a run to be nominated a third time by the Republican party in Chicago. He almost does it. He loses rather narrowly to James Garfield. But he very nearly got it.

Brett McKay: Just as he experienced business failure early in his life, he also had just a serious business setback later in his life.

Ron Chernow: Oh god yeah. He was the victim of a pyramid scheme and Grant’s unbelievable naivete never deserts him. About three or four years before he dies, he enters into a partnership on Wall Street with a young man named Ferdinand Ward, who was lionized as the young Napoleon of finance. Grant imagined that thanks to Ward’s financial wizardry that he, Grant, is worth several million dollars, which would be many million dollars today. Then he wakes up one morning in 1884, and discovers that instead of being worth several million dollars, he’s worth exactly $80, that all the profits had been fictitious, and Ward, like Bernie Madoff had been running a big Ponzi scheme. All the profits were fictitious.

Around the same time, Grant is diagnosed with cancer of the throat and tongue, which is a very excruciating way to die. He had always said that he would never write his memoirs of the Civil War. He thought it was pretentious. But now he’s afraid, he’s dying of cancer, when he dies he was afraid that his wife Julia would be left destitute so he agrees to write his memoirs. They become the great bestseller of the 19th Century, and considered the classic military memoir in American letters.

Brett McKay: Mark Twain was the publisher of that.

Ron Chernow: Yeah, Mark Twain finds out that Grant was about to sign a contract with the Century Publishers. Twain finds out about this and finds out that the Century people have offered Grant 10% in royalty, which Twain feels is criminal. He goes to Grant and says that he will give Grant a 20% royalty, or 70% of the profits. Grant ends up getting 70% of the profits and Twain is not his … Twain is really his publisher. Twain said that his involvement revolved around relatively trivial matters of grammar and punctuation. The memoirs are so brilliantly written that people to this day are convinced that Mark Twain must’ve been the ghostwriter, that surely Ulysses S. Grant could not have written that.

I went down to the Library of Congress when I was doing the research, and I demanded that I be allowed to look at every page of the manuscript. Just about all of it is indeed in Grant’s handwriting, except at the very end you could see that there’s some paragraphs that Grant had dictated, and they’re in the hands of Grant’s son or his stenographer. But Twain did not write it, and frankly Twain could no more have imitated Grant’s style than Grant could’ve imitated Twain’s style. Grant had always prided himself on his writing. He prided himself on writing all his own war time orders. He prided on writing all his own speeches and papers as President. For the people who knew him, the literary triumph of the memoirs was not as great a surprise as it might’ve been for the public in general.

Brett McKay: You describe, just as he stoically faced battle and more, Grant did this stoically. He was in a lot of pain with this throat cancer. There’s a picture in the book of him sitting in a wicker chair, bundled in a blanket, and you can tell he’s probably in a lot of pain but he knows he has to get this done before he dies.

Ron Chernow: Oh absolutely yeah. He’s sitting there all … wool cap on his head, and he has a scarf over his neck. People said the tumor bulging on the side of his neck was the size of a baseball or a grapefruit. The man is in excruciating pain. He said that simply swallowing a glass of water, the sensation was like swallowing a glass of molten lead. This is a gruesome way to die. What he ended up doing, it was great bravery, was that he found that every time he drank a glass of water or he had any food, that the pain would be terrible and he would need to take painkillers, opiates. They would fog his brain. Every day he would try to go for four or five hours without eating or drinking anything just so that his mind would be completely clear for the writing.

He wrote this during the final year of his life, in great pain, knew he was dying and managed to produce a book with more than 300,000 words of sparkling prose. It’s an extraordinary achievement. The lovely thing about writing about Grant, and I hope for people reading the book, is that he just continues to surprise you with what he’s done. Sometimes he surprised you that he keeps on making certain blunders over and over again, but he does keep growing into a much bigger and richer figure throughout his life.

Brett McKay: What remains compelling about Grant in our modern day? As you mentioned, at one point he was listed near the bottom of the Presidents, now he’s kind of rising. What do you think is going on there?

Ron Chernow: I think what’s going on is … I love a line that Walt Whitman said about Grant. He said, “Nothing heroic and yet the greatest hero.” I think that what he meant by that was that Grant was the type of hero who is not trying to be heroic. He was just keeping his head down. In his quiet determined fashion, doing his patriotic duty. In the course of doing that, he became heroic, but he was not driven, as many great figures in history are, he was not driven by a lust for fame, or power, or fortune, or any of those things. The fame, the power, the fortune, those things were kind of a byproduct of doing his military duty of doing his patriotic duty.

This is kind of a sense of honor, and modesty, and integrity, and patriotism, unfortunately was in very short supply in the modern political world, which is a world of salesmanship and self-promotion, all the time. We get it from the White House, but it’s not limited to the White House at all. It’s kind of the style of the world that we live in. I think that there’s something very, very compelling. That story of Ulysses S. Grant, came from a small town, modest, understated man who’s creed was essentially, “I’ll let my deeds speak for themselves. I’m not going to be promoting myself all the time.” He always, from the time he was a young man, he wanted to be recognized for himself, rather than his telling you how wonderful he was. He wanted you to see how wonderful he was, and just let his actions speak for themselves.

Brett McKay: He was an antidote to the world of social media. Well, Ron this has been a great conversation. Thank you so much for your time. It’s been an absolute pleasure.

Ron Chernow: Oh, my pleasure. Thank you so much for inviting me onto your podcast.

Brett McKay: My guest’s name is Ron Chernow. He is the author of some of the most influential biographies. His latest is Grant. It’s available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can also find our show notes at aom.is/grant, where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out The Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoyed this show, you got something out of it, I’d appreciate it if you take one minute to give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. It helps out a lot. You’ve done that already? Thank you, please share the show with your friends. Word of mouth is how this show grows. As always, thank you for your continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.