With our archives now 3,500+ articles deep, we’ve decided to republish a classic piece each Sunday to help our newer readers discover some of the best, evergreen gems from the past. This article was originally published in October 2016.

You’ve probably been to an army surplus store.

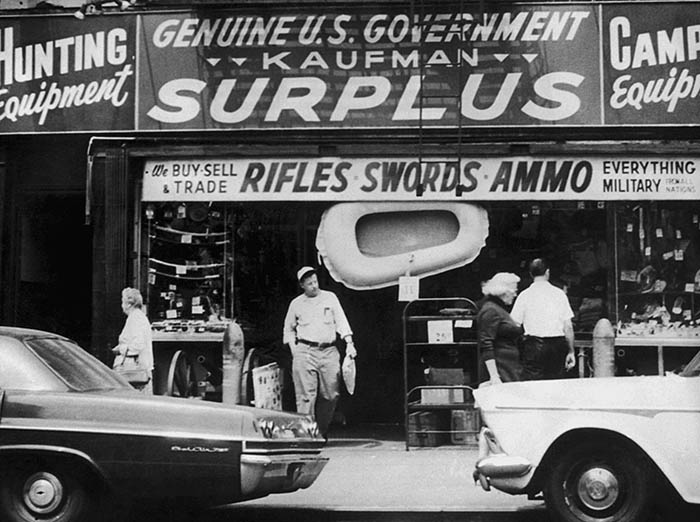

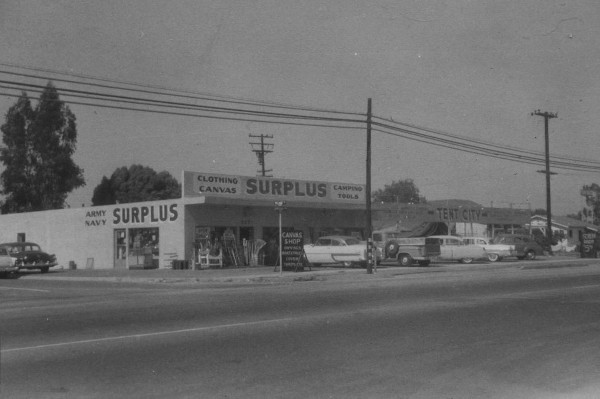

They all look pretty much the same wherever you live. Surplus stores can be found in strip malls in the rough part of town or as stand-alone warehouse-style buildings with corrugated metal roofing and very few windows. They’re easy to miss while driving because they typically only announce themselves with a small yellow sign emblazoned with “Army Surplus” in black lettering.

When you walk in, your nose is met with that distinct army surplus smell: musty canvas mixed with metal and rubber. Flags hang from the ceiling — an American flag, flags from the different branches of the military, a “Don’t Tread on Me” flag. Every conceivable space in the store is filled with product. You’ll see bins scattered throughout the floor filled with gas masks, canvas duffle bags, canteens, and nylon combat belts. Shelves are jam-packed with combat boots, cargo pants, and helmets. And the coat racks are stuffed with pea coats and camo as far as the eye can see. Inside the glass case of the front counter, you’re likely to find antique military items like Nazi paraphernalia, guns used during WWI, and a plethora of knives.

For decades, the army-navy surplus store was the go-to place for individuals looking to find a good deal on products to outfit themselves for camping or hunting, prepare for the apocalypse on the cheap, or simply pick up a stylish pea coat at a bargain price.

There was such a glut of military surplus clothing and gear in the United States during the 20th century you could practically throw a rock in any direction and hit an army surplus store. They were prolific and played a vital role in distributing an over-abundance of government-issued supplies that accumulated during the last century’s wars.

But if you’ve visited an army surplus store lately, you probably noticed they just aren’t what they used to be — that the quality and quantity of the selection of products isn’t the same.

What happened to the once venerable tradition of the army surplus store?

Today we’ll chart its rise and fall.

The Rise of the Army Surplus Store

The army-navy surplus store as we know it today got its start after the Civil War. Up until then, the U.S. government didn’t need to buy supplies in mass quantities for its troops, as it used a militia system for defense. Individual states and militia members themselves were responsible for getting outfitted for battle.

That changed with the War Between the States. War-making became more centralized and industrialized. Instead of relying on states and individuals to provide the gear needed to fight, both the Confederacy and the Union leveraged mass production to equip their troops (the latter having the industrial advantage in this area).

At the end of the war, there was a huge surplus of arms, uniforms, and horse tack sitting on shelves and in warehouses collecting dust. To recoup some of the costs of these leftovers, the U.S. government began auctioning off the supplies in bulk to civilians at heavily discounted prices. While small storeowners from around the country took advantage of these deals, one man in particular turned military surplus into a giant business empire, ultimately creating the business model of the army surplus store we recognize today. His name was Francis Bannerman.

The Bannerman Army-Navy Surplus Empire

Francis Bannerman was born in Scotland in 1851 but immigrated to New York with his family as a child. His father made a living selling goods acquired at auctions, and a young Francis often accompanied him to these sales where he’d pick up big lots of various knick-knacks himself, and then sell them in smaller lots to stores. It was the 19th-century version of eBay-esque arbitrage. On top of this little side hustle, Bannerman created a profitable business selling scrap metal and abandoned ships that he found in the harbor near Brooklyn, New York. All while he was still in primary school.

At the end of the Civil War in 1865, Francis (who, let’s keep in mind, was only 14 years old) used profits from his scrap metal business to acquire large lots of military surplus at government auctions. One particularly successful acquisition netted him over 11,000 captured Confederate guns. Because the teenage entrepreneur bought this gear at such heavily discounted prices, he was able to mark it up so the products remained a bargain for the customer, while still netting himself a nice profit.

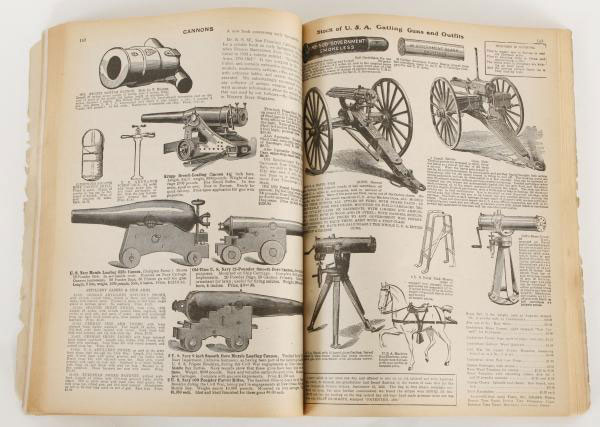

Francis kept all his military surplus inventory in various places around New York City, but eventually consolidated it all in one store on Broadway in Manhattan: the world famous Bannerman’s Army & Navy Outfitters. Known simply as “Bannerman’s,” the store eventually grew to cover a block in length and seven floors in height, encompassing over 40,000 square feet of floor space. It also issued a 350+ page Sears-Roebuck-like catalog from which subscribers around the globe could mail-order horse saddles, swords, African spears, Civil War rifles, and even cannons if they fancied.

Explorers, military commanders, and adventurers of all kinds were some of Bannerman’s biggest clients. Admiral Matthew C. Perry and Frederick Cook outfitted their expeditions using Bannerman’s catalog. Mercenary soldiers fighting in the Spanish-American War and conflicts in the British empire would go to Bannerman’s to get the arms and gear they needed before heading to battlefields abroad.

In the latter quarter of the 19th century, Bannerman continued his prolific military surplus buying. The Spanish-American War was a particular boon to Bannerman’s business, as he won several bids on thousands of captured Spanish rifles and millions of rounds of ammunition, and ended up acquiring 90% of the war’s surplus.

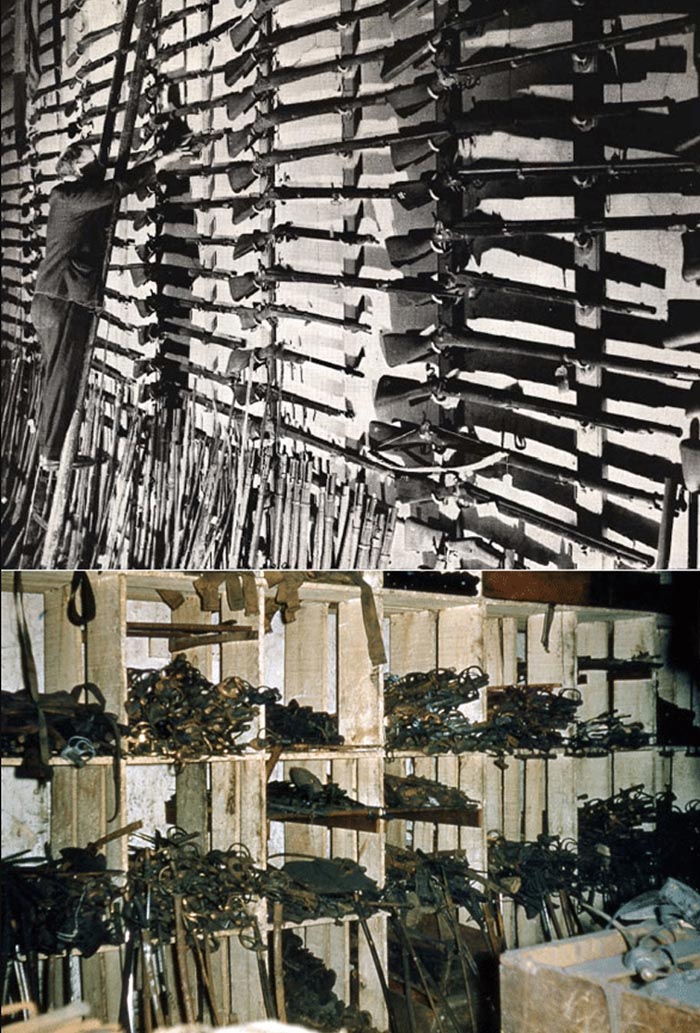

Whenever the military switched to a new kind of uniform, weapon, or equipment, Bannerman was there to scoop up the discarded models and bring them back to NY. By 1900, he had run out of space in his colossal Army & Navy Outfitters store, and didn’t deem it safe to store his cache of thirty million surplus munitions cartridges in the city. So, he bought an island on the Hudson River upon which to build a large storage facility. Styled like a Scottish castle, the surplus warehouse was constructed out of cement (that he acquired at auction, of course) and was accompanied on the island by a residence for Bannerman and his family.

As global conflict increased in the early 20th century, Bannerman’s was there to supply the armies of nations around the world. For example, the Japanese military shopped at the surplus store to stockpile arms and munitions during the Russo-Japanese War. African and South American countries engaging in wars of independence were also big customers for Bannerman. When the United States found itself in WWI and short of supplies, he gave the military the guns and munitions needed to help bootstrap the war effort.

After Bannerman died in 1918, his surplus empire began to crumble, both literally and figuratively. Huge piles and stacks of firearms, bullets, artillery shells, swords, and uniforms began to molder and gather dust in his Manhattan store and island arsenal. The cache was not only disorganized, but dangerous; in 1920, 200 tons of shells and powder exploded inside a building on the island’s storage complex.

While his family continued the Bannerman business, mail-order and retail sales began to dwindle in the 1930s. Unlike the Civil War, there wasn’t much military surplus after WWI, due to the United States’ comparatively limited, short-term involvement in the conflict. So Bannerman’s was relegated to continuing to primarily sell their 19th-century wares, for which there was naturally diminishing demand.

What’s more, federal and state firearms acts passed in the 1930s prevented Bannerman’s from selling military weapons to civilians, as well as to foreign countries. Consequently, the enormous arsenal of weaponry Francis Bannerman had accumulated during his lifetime became useless.

In its heyday, this wall of the Bannerman castle served as a billboard to those passing by boat and train. After decades of fire, collapse, and neglect, only the exterior of the castle remains today. Image from Sometimes Interesting.

While Bannerman’s family continued to use and periodically visit their island, it was all but abandoned in 1950 when the only ferry which serviced its shores sunk in a storm. Interest in the business waned at the same time. None of Bannerman’s descendants wanted to continue running the Broadway store, so the decision was made in 1959 to sell the famous institution and move the remaining inventory to a warehouse on Long Island where it was still sold through the catalog. By the 1970s, even Bannerman’s catalog sales ceased.

The Golden Age of Army Surplus Stores

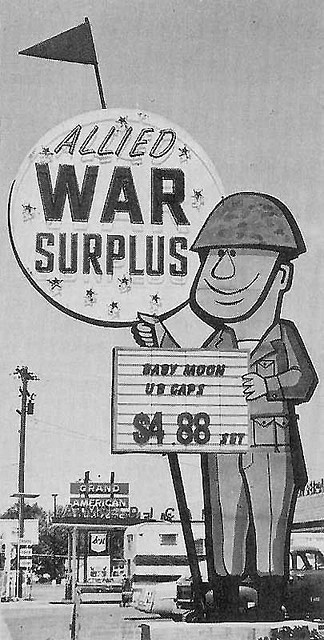

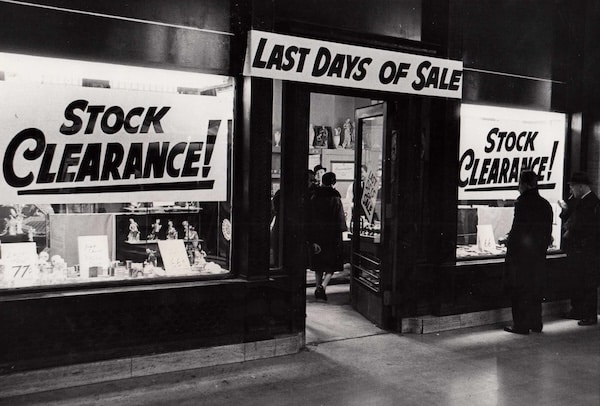

While Bannerman’s Army & Navy Outfitters faded into obscurity, it provided the blueprint for the thriving military surplus industry that sprung up after World War II. Rationing on the home front and the enormous amount of excess government-issued equipment produced by America’s “arsenal of democracy” combined to explode the growth and popularity of surplus stores in the aftermath of the Big One; huge amounts of wartime leftovers flooded the market, and after years of deprivation, the public was eager to get its hands on it.

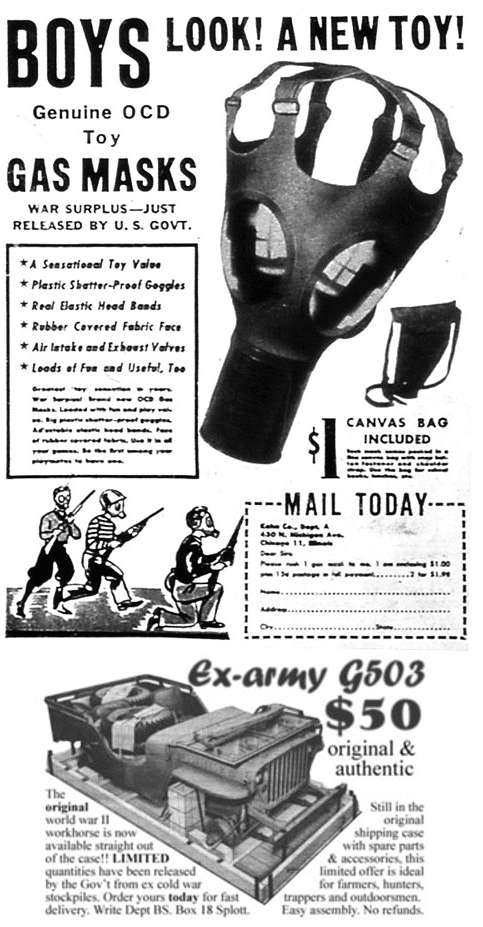

Like Bannerman’s, surplus stores after WWII not only offered products through brick and mortar stores but by mail-order as well. Even a jeep. Surplus companies often placed ads in boys’ magazines; young men, who idolized returning GIs, prized anything and everything they had used — even gas masks, which were marketed as “A sensational toy value” and “Loads of fun and useful, too.”

Enterprising businessmen from around the country followed the example Bannerman set after the Civil War by buying massive lots of the surplus military gear that existed in the aftermath of WWII. At a single auction, a buyer could get all the inventory he needed to outfit an entire army surplus store. There was so much stuff — uniforms, canteens, flashlights, radios, even jeeps — that it would take years for the U.S. government to dole it out to these middlemen, and even decades before these buyers could sell it off in their shops.

Thanks to the United States’ significant involvement in the Vietnam War, army surplus stores were able to restock their dwindling WWII inventory with updated military surplus. If you visited a surplus store as a kid in the 1980s or early ‘90s, a lot of the stuff you saw was probably from Vietnam.

While no single establishment was able to duplicate the enormity of Bannerman’s Army & Navy Outfitters, the period from after WWII and until the early 1990s could be considered the “Golden Age of Army Surplus Stores.” There was just so much stuff available, and it was so widely dispersed and easily accessible to the public. Instead of ordering something from a catalog, you just had to drive a few miles to one of the many surplus stores in your city.

But just as Bannerman’s military surplus business slowly faded away due to changing circumstances, so too has the large and thriving army surplus industry that existed in America for half a century. How that decline happened, we turn to next.

The Fall of the Army Surplus Store

Army surplus stores still exist. You probably have one in your city. But it’s probably not the same kind of army surplus store you may have visited back when you were a kid. If you’ve been to one recently, you likely noticed that fewer of the products they carried were actually “military surplus.” Sure, the stuff might look military-ish, but it was likely bought from a foreign company that manufactures military-ish products instead of from the U.S government, or even a foreign government. You’ll also see product in the store that you probably wouldn’t consider “military surplus” like work pants and shirts, consumer camping gear, etc. Basically, in today’s army surplus stores there’s less army surplus.

Two big factors are contributing to the decline of true military surplus products in the marketplace: the changing nature of war in the late 20th century and online shopping.

War has changed dramatically since Vietnam. Instead of engaging in large-scale conflicts that require a draft and many millions of boots on the ground, the U.S. military has shifted to a much more streamlined and surgical approach to battle — one that involves a smaller, all-volunteer force. For example, there were over 10 million American soldiers who served in Vietnam, while only 2.5 million served in the most recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Because our most recent conflicts have required fewer soldiers, the military has required less equipment. Because the army requires less equipment, there’s less military surplus to go around to all the army surplus stores around the country.

Compounding the shortage due to smaller, more limited military engagements is that — thanks to the internet — army surplus stores now have to compete with the government itself in selling surplus military inventory. The U.S. government has an online store where the public can buy military surplus direct, thus cutting out the army surplus middleman and saving the buyer some money. Thanks to competition from the government’s direct-to-consumer sales, army surplus storeowners have had to slash retail markups on their products from a stellar 100% to a ho-hum 30-50%.

Because of these two changes — streamlined wars and the internet — the once robust army surplus store industry has taken a hit. There’s just less inventory to go around, and less money to be made in the business.

To keep shelves stocked with military goods, even though there’s less government-issued military surplus available, stores have taken to importing military surplus “knockoff” products — stuff that looks like military surplus, but really isn’t. While these imported knockoffs have helped surplus stores stay alive, as Dr. Frank Arian, owner of Surplus Today, notes, this increase of imported military surplus knockoffs has hurt the brand cache of army-navy stores: “Imports have negatively affected business by diluting, to a large degree, the very foundation upon which these stores were built: genuine government military surplus. Imports are not government, not military and not surplus. Can you still call a store ‘surplus’ if it has 85% imported copies?”

Like any other industry that’s been disrupted, army surplus stores have made innovations to keep themselves afloat. For example, some stores have become airsoft gun dealers and even have airsoft courses inside or near their facilities. This business move has worked well for many of the stores who’ve done it. Diehard airsoft competitors can pick up a new gun and extra pellets while picking up cargo pants, gloves, and camo for their next competition too.

Other surplus stores have taken to offering various classes in their stores like workshops on wilderness or urban survival. These classes provide two sources of revenue. First, there’s the income from the class itself. Second is the revenue that comes from people buying stuff in the store when the classes are held.

Still other stores have shifted their focus from being military surplus dealers to antique military dealers. 20th-century military gear — once considered ordinary surplus — is now considered “vintage,” and collectors are willing to pay top dollar for these antiques. Army surplus stores that have been in business for awhile have used their networks developed over the years to become savvy peddlers of 20th-century military collectibles.

Stores that have made changes like these will likely survive and even thrive in today’s market; the stores that don’t, won’t. Army surplus stores will probably be with us for decades to come. They just won’t look like your grandpa’s surplus store, though they might still smell like it.