With our archives now 3,500+ articles deep, we’ve decided to republish a classic piece each Friday to help our newer readers discover some of the best, evergreen gems from the past. This article was originally published in November 2014.

“Consider the reality of today’s job market. We have a massive skills gap. Even with record unemployment, millions of skilled jobs are unfilled because no one is trained or willing to do them. Meanwhile unemployment among college graduates is at an all-time high, and the majority of those graduates with jobs are not even working in their field of study. Plus, they owe a trillion dollars in student loans. A trillion! And still, we push a four-year college degree as the best way for the most people to find a successful career?” -Mike Rowe

For better or for worse, what we do for a living often defines us. It’s one of the first questions we ask people when we meet them for the first time. It’s where we will end up spending 90,000 hours of our life, over the course of 40-some years. Unfortunately, most people count themselves as unhappy with their work (by two to one worldwide!). Pop culture endlessly makes fun of the drone-like office employee, and yet that’s where most of us are.

Is there a better way? Are there careers that would engage us, provide for us, and make us happier? The answer is a resounding yes, but with an important caveat: young men should expand their search for such a career beyond the white collar gigs that are pitched to most of us from our first day of secondary ed. For modern high school students, the default path is graduating from high school, going on to a four-year college, and then finding work in an office (in fact, there are nearly twice as many business degrees handed out as any other single degree). But college simply isn’t for everyone. And neither is a lifetime of sitting at a desk. Luckily, there’s a world of satisfying, good paying jobs beyond the cubicle wall.

Today we will begin a 3-part series encouraging young men (or older men looking for a career change) to consider learning a trade. In this first article, I’ll point out four of the common myths and stereotypes surrounding the trades. In the second article, I’ll get into the benefits of being in the trades (of which there are many). After that, we’ll get into the nitty-gritty about how to find careers in skilled labor. Then once the series is done, we’ll do a bunch of So You Want My Job interviews with skilled laborers in order to get a personal, inside look at what it’s really like to work as a tradesman.

Let’s get started by exploring the myths that have made the path of blue collar work something most young men don’t even contemplate taking.

The 4 Myths of Skilled Labor

Welders, plumbers, electricians, machinists — they’re in higher demand now, and have greater benefits, than they ever have. While our nation endures record unemployment for young people, there are literally thousands upon thousands of trades jobs available (very good jobs, mind you) that go untaken because there aren’t skilled laborers to take them.

This wasn’t always the case, though. A century ago, the nation’s workforce looked much different. In 1900, 38% of all workers were farmers, with another 31% in other trades such as mining, manufacturing, construction, etc. Only about 30% of the workforce labored in service industries (defined as providing intangible goods). Fast forward 100 years, and you see almost the exact reverse. In 1999, over 75% of the labor pool worked in the service industry (most often in an office), and farming saw a precipitous decline to a mere 3%, and other trades down to 19%.

While the number of laborers in the skilled trades has sharply declined, there’s still a great need for this type of work. These blue collar men and women literally keep our nation’s infrastructure intact – from our electrical systems, to our plumbing, and even the nuts and bolts that keep our buildings together. There is an ever-widening skills gap occurring in our nation because of the fact that young people aren’t considering those careers. This means there are good jobs available, but no talent to fill them. It’s for this reason that Mike Rowe, former host of the popular show Dirty Jobs, is advocating for a return to blue collar work through his foundation and scholarship fund. And it’s not just him; high schools across the country have begun to recognize the need for skilled work, and are becoming career training centers rather than simply liberal arts institutions that exist solely to prepare students for college. State politicians are campaigning and recruiting on behalf of construction companies, because state-funded projects simply can’t find tradesmen to weld or to install elevators.

There is good work and good money to be had in the trades, so why aren’t more young people picking up their hard hats? I talked with Kevin Simpson from Pickens Technical College, as well as a couple folks from Emily Griffith Technical College (both here in the Denver area), to find out their take. What do these colleges see as the main culprit? Stereotypes. Our nation’s workers are holding on to stereotypes about blue collar work and about trades that may have been true fifty years ago, but simply aren’t the case anymore. There are a number of myths that folks hold about skilled trades careers; let’s take a look and get to work dismantling them:

Myth #1: Blue-collar work is “beneath” white-collar work.

“Blue collar and white collar are two sides of the same coin, and as soon as we view one as more valuable than the other, we’ll have infrastructure that falls down, we’ll have a skills gap.” -Mike Rowe

Since ancient times, manual labor has been looked upon as a job for slaves; for the lesser. The upper classes did their work with their minds — philosophized, ran cities and nations, sold goods (though for a long time even merchants were looked down upon, since in handling money they were inferior to those who made their living purely through cognition). Egyptians, Greeks, white Americans in the 1800s — these groups of people spurned physical labor, and forced others to do it for them. It was hard, and as our human tendency is to seek comfort where we can, it was a mark of status to be above it.

During the industrialization period at the turn of the 20th century, manual labor lost some of its stigma. It was where the economy was going, it was where most of the jobs were, and there was the sense of it being absolutely essential to the building up of the country’s quickly expanding roads and cities. As learning a trade was a definite step up from being a cog in the factory system that had arisen in the 1800s, skilled craftsmen gained a greater measure of respect.

After WWII, however, more and more folks began enrolling in 4-year colleges, spurred on in large part by vets getting their tuition taken care of by the US government through the GI Bill. Virtually unlimited free education? Who wouldn’t take that deal? If you could make a living with your mind and not have to physically work hard, all the better.

As the 4-year education trend gained steam, teachers and administrators began to play more of an advisory role towards students, helping them decide where to go, which colleges they could get into, etc. These counselors guided their best and brightest students towards prestigious 4-year institutions, while shuttling poorer performing students towards tech or vocational schools. Learning a trade became thought of as the career track for those who couldn’t hack it in college, and no young man wanted to think of himself as second-rate.

The increasing number of college graduates coincided with an economy that was shifting from manufacturing and agriculture to a more intellectual and service-oriented market. Today, over three-quarters of Americans work in some kind of white collar position.

Thus, with the image of blue collar work diminishing and the market for white collar jobs expanding, it began to be cultural dogma that if a young person wanted a good, respectable, well-paying job, the only option was to go to college. More education was always seen as better, the assumption being that the more education someone has, the smarter they are, and the better job or life they’ll have later on. Trades, on the other hand, often require less schooling (by about half, in most cases, but sometimes as little as a third or quarter as much), and so this career path became associated with lesser prospects for success.

Thus, by the latter third of the 20th century, both the respectability and desirability of learning a trade had greatly diminished, while the distance between white and blue collar workers had exponentially grown.

Yet this belief that different work means lesser work, is hardly inviolable. And it’s about time we questioned it, and asked, “What defines ‘better’ anyway, in terms of a career?” Trades jobs have in many cases become better paying and more stable than most office jobs. In the past, it was a sign of cultural status to be a businessman rather than a lowly factory worker. As our economy shifted to the service sector, the difference between wages and quality of life was great enough that being a businessman really was a better job. But today, in many trades or blue collar professions, those gaps are simply no longer present based on how we define good jobs — largely in terms of pay, stability, autonomy, benefits, work-life balance, etc.

Further, learning a trade need not mean that you’re not cut out for college, or that your mind is second-rate. You can be quite smart and still choose to make your living with your hands. The idea that you can either be an intelligent white-collar worker, or a dumb blue collar brute, is an extremely false dichotomy. You could easily be an electrician during the day, and a devourer of the great books by night.

So too, it simply isn’t the case that your day-to-day work in the trades won’t engage your mind:

Myth #2: Blue-collar work isn’t creative or intellectually stimulating.

Another barrier to the trades is that there is a false notion that the work is mindless and tedious. Young people today want to be intellectually stimulated by what they do; they want to be creative and innovative, like Steve Jobs or Mark Zuckerberg. The desire to create is a worthy one and is actually a defining marker of maturity. The issue is that we limit ourselves in how we think we can attain those qualities in our workplace. Surely it can only happen in a modern, minimalist office with a Mac and iPhone at hand, a big whiteboard on the wall, and fancy coffee at the ready, right? How on earth could creativity happen in a blue uniform with an auger in hand, getting to intimately know the inside a toilet?

The reality is that any job in the world includes mindless and tedious tasks. That’s just how it goes. In fact, a lot of office jobs are more tedious than you’d expect. A recent study showed that a staggering 90% of office workers waste time during the day on non-work-related activities — largely, surfing the web. Makes sense, though, doesn’t it? Nobody can be fully productive over the course of an 8-hour workday. Perhaps what’s more surprising is that over 60% are wasting at least an hour at work, and 30% are wasting 2+ hours. Why is this? The vast majority state that they’re either unchallenged, unsatisfied with their work, or are plain bored. Does that sound like an invigorating, stimulating workplace?

It could pretty easily be argued that the trades offer more intellectual stimulation than the majority of office or even entrepreneurial jobs out there. Think about the residential plumber or electrician. He’s out and about all day, seeing new places, meeting new people, and grappling with new problems. There could be any number of issues as to why a toilet isn’t unclogging or why a particular outlet isn’t working. The tradesman will start off testing the standard issues and fixes, and if that doesn’t work he’ll utilize increasingly complex troubleshooting procedures to determine the root cause of a problem. He’s executing problem solving skills and quick thinking in a way that many of us in white collar jobs never have to. The skilled trades simply offer a different type of creative outlet than a job with a startup in a trendy office. That’s what Matthew Crawford, author of Shop Class as Soulcraft, found to be the case. After going to college and taking a mind-numbing white collar job, he discovered that being a motorcycle mechanic actually provided him far more stimulation and satisfaction than he had ever gotten working behind a desk:

“The satisfactions of manifesting oneself concretely in the world through manual competence have been known to make a man quiet and easy. They seem to relieve him of the felt need to offer chattering interpretations of himself to vindicate his worth. He can simply point: the building stands, the car now runs, the lights are on. Boasting is what a boy does, because he has no real effect in the world. But the tradesman must reckon with the infallible judgment of reality, where one’s failures or shortcomings cannot be interpreted away. His well-founded pride is far from the gratuitous ‘self-esteem’ that educators would impart to students, as though by magic.”

Listen to my podcast with Mike Rowe about the trades:

Myth #3: You have to follow your passion, and welding isn’t your passion.

“Follow your dreams!” is a phrase that our culture is in love with these days. The idea is that in high school or college you’ll realize what you love to do, and then get an education that follows so that you can have your “dream job.” What this actually ends up doing though is simply filling teens and twentysomethings with a whole lot of angst about what to do with their lives. When options are seemingly limitless, we have a really hard time choosing. We end up thinking that our lives are ruined if we don’t find that one thing we really love doing.

Thankfully, and although this is extremely hard to realize sometimes, your life isn’t limitless. The reality is that most people, especially in their late teens and early twenties, have no idea what they actually want to do. But because of the stereotypes that surround blue collar work, they go to business or law school by default, because having an office job is better than being an elevator technician. How could anyone possibly be passionate about fixing elevators? The answer to that might surprise you.

There’s a lot of work being done to show that passion or fulfillment in your workplace doesn’t come through “following your dreams,” but a whole host of factors that are very different from that outdated advice. In fact, research is finding that passion follows hard work and being good at what you do, rather than precedes it. What this means practically is that if you grease your elbows and master the trade of being a plumber, you’ll actually come to enjoy your work.

The truth is that our “passion” ends up being a combination of what we’re good at and what we work hard at. Fulfillment at work is more about mastery and autonomy and balance than about a pre-existing passion. Love for your work rarely springs from fulfilling a built-in burning desire in your heart to do that one thing in the world and that one thing only. In fact, turning a hobby you’re passionate about into a job is often a surefire way to kill that burning desire good and dead.

To learn more about the myth of finding your passion, I cannot suggest strongly enough that you listen to Brett’s podcast with author Cal Newport. It’s one of my favorite AoM podcasts of all time, and one I think every teenager and twentysomething (and beyond, really) should listen to.

Myth #4: Dirty, hard work is undesirable work.

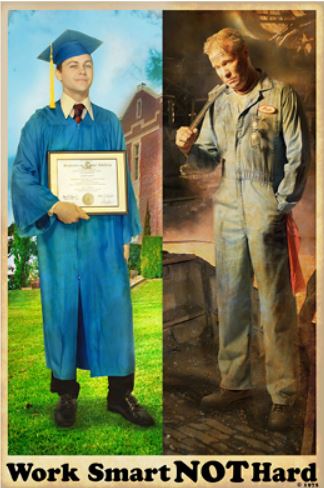

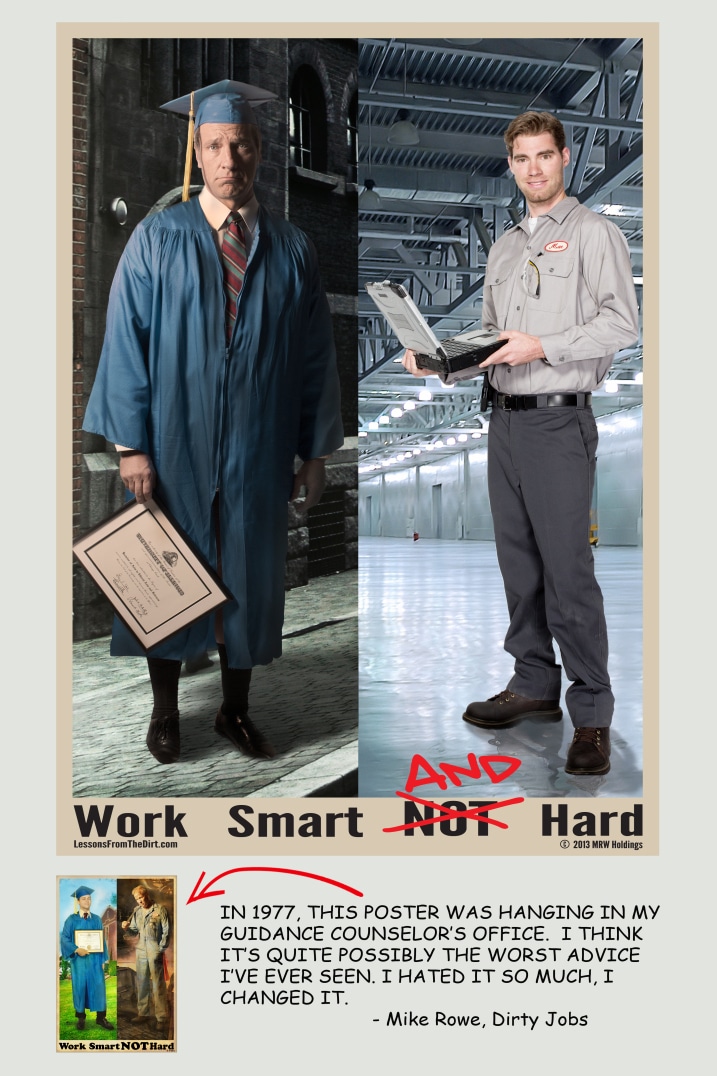

In Mike Rowe’s book, Profoundly Disconnected, he tells the story of being in his high school guidance counselor’s office in the late 1970s and seeing the above poster. “Work smart, not hard.” While the sentiment may have been more akin to “Hard work alone is good, but being smart is important, too!” the high school student probably read it as, “Yes! I don’t have to work hard if I’m smart!” The students who saw these posters in the late 70s and early 80s are now running companies and passing that belief onto younger generations, even if in subconscious ways. Beyond those CEOs, there are authors, podcasters, “lifehackers” — all advocating working smarter rather than harder, thereby bypassing the menial, boring stuff. Heck, you can work a 4-hour week and make millions! (Or so is claimed.)

Thankfully, with Mike Rowe’s help, that message is being put in its rightful place: the garbage. He’s replacing it with a new message: “Work smart AND hard.”

The truth is that the world belongs to those who hustle. Ambition without elbow grease won’t get you anywhere. Even this generation’s career heroes — the late Steve Jobs, Zuck, Richard Branson — work(ed) insanely hard at their jobs. You only see glitz, but they’ve burned more than their fair share of midnight oil.

Yeah, you think, but working hard with your brain sounds better than working hard with your brawn. It’s true that there are different kinds of hard work, but they’re both hard in their own way. Each type of hard has its own pros and cons, and the hardness of physical labor doesn’t automatically make anyone less happy than the difficulty in typing at a computer all day.

Over the course of Mike Rowe’s stint as host of Dirty Jobs, he came to discover something very interesting about hard, dirty work. Before he started that job, when he was in the brainstorming phase of the show, he expected the people he ran into to really hate their work. But one after another, almost without fail, they loved it. He in fact called them the happiest group of people he’s ever seen. I’ll repeat: passion for your work will follow your working hard at something and achieving mastery in it. Swinging a hammer every day is never going to be as hard as filing TPS reports from 9-5, if you’re hating every single minute of it.

Beyond hard work, many trades are also simply dirty and grimy. We’ve recently highlighted our culture’s obsession with being clean. Antibacterial soaps and boiling stuff rule the day. This attitude carries over into how we view work. We want things to be neat and tidy and minimalist, just like that clean and beautiful Apple laptop sitting on your clean desk.

When we grow up uber-clean as children, we end up with an aversion to stuff that’s dirty or gross. And the reality is that a lot of tradesmen end the day with dirty hands. While there are some trades that don’t get grimy, Kevin Simpson estimates that about 90% do. Plumbers, electricians, construction workers — these are jobs where you shower at the end of your day, not the beginning.

In a sterile society, dirty jobs become undesirable. Perhaps that’s why their pay is increasing and job demand in the trades is higher than ever before. Mike Rowe believes that our culture is heading to a point where an hour of plumbing is going to cost more than an hour with the psychologist. If you can get over your fear of dirt, grime, and sweat, you have the potential to make a far better living than your office-dwelling peers. And you may even discover that it feels good to be using your body and hands every day, that it’s satisfying to be in touch with the elements, even when those elements are grimy, and that nothing feels better than taking a well-earned shower when you actually have dirt to clean off.

We’ve now covered the myths of working in the trades. In a couple weeks, we’ll get into the benefits and why every young man, or anyone considering a career move, should look at skilled labor. For now, I’ll leave you with a beautiful ode to manual labor in the form of an excerpt from a speech given by Luciano Palogan to the Philippine School of Arts and Trades in 1910:

Nothing great or good can be accomplished without labor and toil.

The days when manual labor was looked upon as a disgrace and the time when it was considered as the occupation of the degraded man have passed away. The days have disappeared when the student walked a block to call a “muchacho” to carry his books to school. And the unsoiled, soft, and cushion-like hands, the pride of the young man a few years ago, have gone out of fashion.

The Filipino has turned over a new leaf. He now realizes that manual labor is not a disgrace but an honor; that it is not manual labor that places the man in a low rank among men in society, but it is manual labor that raises him to a higher standard of life.

Manual labor squeezes the sweat out of the muscles and roughens the hands, but in turn it restores strength and increases their size. Roughness of the hands and scorchings of the sun on the face are the truest badge that a man can wear to show that he belongs to the great society of the workers and not of drones.

Read the Entire Series

4 Myths About the Skilled Trades

5 Benefits of Working in the Skilled Trades

How to Start a Career in the Trades