“Oratory is the parent of liberty. By the constitution of things it was ordained that eloquence should be the last stay and support of liberty, and that with her she is ever destined to live, to flourish, and to die. It is to the interest of tyrants to cripple and debilitate every species of eloquence. They have no other safety. It is then, the duty of free states to foster oratory.”

-Henry Hardwicke

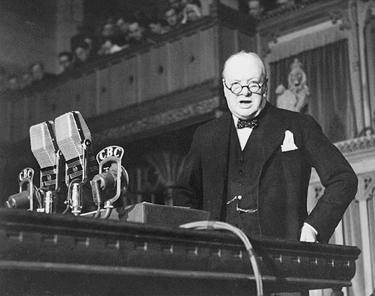

The power of the spoken word is undeniable. At all the great crisis and hinges in history, we find great speeches which swayed the outcome. Great speeches have motivated citizens to fight injustice, throw off tyranny, and lay down their life for a worthy cause. Words have drawn meaning out of tragedy, comforted those who mourn, and memorialized events with the dignity and solemnity they deserved. Words can move people to risk life and limb, shed tears, laugh out loud, recommit to virtue, change their life, or feel patriotic. By weaving and spinning words into great tapestries of art, a man can wield an almost god-like power. Of course, even the most malicious leaders have known this and sought diligently to hone this skill for nefarious purposes. The power of speech can be used for good or evil and comes with great responsibility. Those who uphold virtue and goodness must be prepared to speak as masterfully as those who seductively and smoothly seek to convince the public to abandon its values and principles.

What is oratory?

“Not until human nature is other than what it is, will the function of the living voice-the greatest force on earth among men-cease. . . I advocate, therefore, in its full extent, and for every reason of humanity, of patriotism, and of religion, a more through culture of oratory and I define oratory to be the art of influencing conduct with the truth set home by all the resources of the living man.”

-Henry Ward Beecher

All oratory is public speaking, but not all public speaking is oratory. A teacher’s lecture, the best man’s speech, a political candidate’s stump speech, all of these things are not necessarily oratory, but they can be elevated to that status.

If public speaking is fast food, oratory is a gourmet meal. Not in pretentiousness or inaccessibility, but in the fact that oratory exists above the ordinary; it is prepared with passion, infused with creativity, and masterfully crafted to offer a sublime experience. Oratory seeks to convince the listener of something, whether that is to accept a certain definition of freedom or simply of the fact that the recently deceased was a person worthy to be mourned.

Oratory has been called the highest art for it encompasses all other disciplines. It requires a knowledge of literature, the ability to construct prose, and an ear for rhythm, harmony and musicality. Oratory is not mere speaking, but speech that appeals to our noblest sentiments, animates our souls, stirs passions and emotions, and inspires virtuous action. It is often at its finest when fostered during times of tragedy, pain, crisis, fear, and turmoil. In these situations it serves as a light, a guide to those who cannot themselves make sense of the chaos and look to a leader to point the way.

The history of oratory

Oratory in Greece

While the spoken word has been central to humanity since our species began to vocalize, it was in ancient Greece that speech would be raised to an art and true oratory would be born. A “golden age of eloquence” was ushered in by the statesman, general, and master orator Pericles. His funeral oration was perhaps the first great speech to be written and prepared for the public, and set the standard for all orations to come. Yet it is Demosthenes who is remembered as the greatest orator of Greece and perhaps all time. His speaking ability roused an Athenian people, deep in an apathetic slumber, to fight the threat Philip of Macedon posed to their liberty.

Yet the practice of oratory was not confined to the elites of Athenian society. Oratory was considered one of the highest arts, even a virtue. It was an essential part of every man’s education, the foundation upon which all other academic pursuits and disciplines were built. The mastery of oratory was considered an essential part of being a well-rounded man.

Oratory blossomed so splendidly and reached such an apex in ancient Greece because of its central function in public life. Athens’ democratic government marshaled every male citizen into politics. Any citizen could be called upon or inspired to sway others to the merits or criticisms of a particular piece of legislation. Laws were few and simple, giving judges considerable latitude in applying justice and lawyers great flexibility in making their case. The assembly, council, and courts were thus filled with vigorous debate and brilliant oratory.

Oratory in Rome

The art of oratory was slow in coming to Rome, but began to flourish when that empire conquered Greece and began to be influenced by its traditions. Roman oratory thrived in the courts, Comitia (assemblies where people debated the passing of laws), and Senate. Roman oratory borrowed much of its style from Greece, although there were differences. The Romans were less intellectual than the Greeks, their speeches less meaty and studded with more stylistic flourishes, stories, and metaphors. Nevertheless, Roman oratory was still a vibrant art and produced its own virtuoso: Cicero. Cicero’s “Catiline Orations” exposed a plot to overthrow the Roman government and did so with masterful eloquence and skill.

Great forensic oratory passed away with the fall of the Roman empire for “eloquence cannot exist under a despotic form of government. It can only be found in countries where free institutions flourish.” Tacitus, a century after Cicero’s death, lamented in the “Causes of the Corruption of Eloquence” that “the speakers of the present day are called pleaders, and advocates, and barristers, and anything rather than orators.” Lawyers began to hire claquers to attend their speeches and applaud generously, leading Pliny to note, “You may rest assured that he is the worst speaker who has the loudest applause.”

Modern Oratory

As democracy waned, so did great oratory. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, oratory was largely confined to the religious sphere. But it would be revived in the 18th centuries as France, England, and America created parliamentary bodies of government and the issues of liberty and freedom burned brightly in debates.

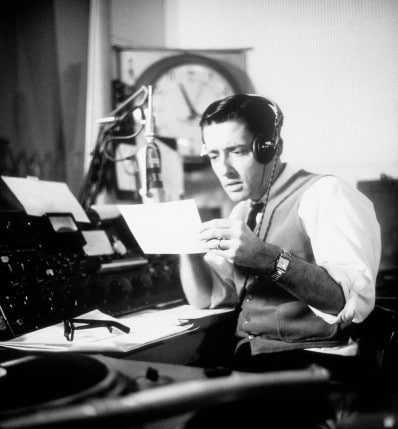

Great oratory began its current decline with the administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Taking office during the Great Depression, FDR soon began his famous fireside chats. The country was demoralized and frightened, and Roosevelt’s warm, grandfatherly voice poured into millions of Americans homes, bringing a sense of comfort and security.

After FDR, Americans expected the same “folksy” speaking approach from all their presidents. Grand, eloquent speeches were considered a bit suspect, smacking of pretension and the lack of a common touch. Yet the reception and praise given to Barack Obama’s speeches suggest that there has been an untapped hunger among citizens for oratory that will inspire them and touch on their ideals (although the ancient Greeks would have criticized Obama’s speeches for sometimes emphasizing style over substance).

While a few great orators exist today, the art has generally fallen into disregard. When a man is called upon to speak, he often hems and haws, boring his audience to tears. It should not be so, gentlemen. It is time to resurrect and cultivate the art of oration.

Becoming a great orator

“Oratory is the masculine of music.”

-John Atgeld

While most men will never summon troops into battle or debate a Congressional bill, every man should strive to be a great orator. Whether it is giving the best man speech, arguing against a policy at a city council, making a proposal at work, or giving a eulogy, you will be asked to publicly speak at least a few times in your life. Don’t be a man that shakes and shudders at that thought. Be a man who welcomes, nay, relishes the opportunity to move and inspire people with the power of his words. When a speaking opportunity arises, be the guy everyone thinks of first.

Being a great orator takes work. You must do the following thing if you wish to master the craft:

Practice, practice, practice:

“The history of the world is full of testimony to prove how much depends upon industry. Not an eminent orator has lived but is an example of it. Yet, in contradiction to all this, the almost universal feeling appears to be, that industry can affect nothing, that eminence is the result of accident, and that everyone must be content to remain just what he may happen to be. . . For any other art they would have served an apprenticeship and would be ashamed to practice it in public before they had learned it. . . But the extempore speaker, who is to invent as well as to utter, to carry on an operation of the mind, as well as to produce sound enters upon the work without preparatory discipline, and then wonders why he fails!”

-Henry Hardwicke

The great myth perpetuated about public speaking is that talent in this area is inherent and inborn and cannot be learned. But our manly forbearers knew better. The great orators of the world from Cicero to Rockne practiced the art of oratory with resolute single-mindedness. Demosthenes exemplified this drive particularly well. As he was a child he was weak and awkward in both body and speech. But he determined that he would become a great oratory. Like TR, he built up his body with vigorous exercise. And he did a series of unusual tactics to hone his speaking skills. He would go to the ocean and attempt to recite orations louder than the waves. He then isolated himself in a cave to put full focus on the attainment of his goal. In order to avoid being tempted to leave the cave before he had mastered the art of oratory, he shaved half his head bald, knowing he would be subjected to ridicule were he to show his face in that state. In an attempt to improve his enunciation, he recited speeches while his mouth was filled with pebbles. He daily practiced his speaking in front of a mirror, improving any defect in his delivery or bodily movements. Finally, he had a nervous tic of raising one shoulder while he spoke. So to correct this, he hung a sword above that shoulder which would cut him were he to raise the shoulder. His work paid off handsomely; he became the one of the greatest orators of all time.

“The speech of one who knows what he is talking about and means what he says-it is thought on fire.” -William Jennings Bryan

No grammatical garnish or oratorical flourish can add as much to a speech as good character. The very hint of hypocrisy will doom even the most eloquent speech. Conversely, when you are virtuous, honest, and earnestly committed to that which you speak of, this inner-commitment will tinge each word you utter with sincerity. The audience will feel the depth of your commitment and will listen far more intently then when they know it is mere claptrap.

Study all the arts

“In an orator, the acuteness of the logicians, the wisdom of the philosophers, the language almost of poetry, the memory of lawyers, the voice of tragedians, the gesture almost of the best actors, is required. Nothing therefore is more rarely found among mankind than a consummate orator.” -Cicero

In order to appeal to noblest and finest sentiments within your audience, your speeches must be filled with allusions to the greatest characters, events, and artistic expressions of history. Oratory thus combines all of the arts into one expression. You must keep abreast of current events and study human nature, religion, science, literature, and poetry. Read the newspaper. Watch great films. Read a least a paragraph of great literature each day. Do not simply frequent blogs and media sources that flatter your pre-existing view points! A great orator must be aware of the counterarguments your critics will raise and deftly address and defuse them before anyone else has the chance to.

Immerse yourself in great oratory

Take as your coaches and mentors all the great orators of the past. Read their speeches. Study the way in which they constructed their sentences, how the placement and arrangement of words builds rhythm, how the choice of words and stories creates vivid imagery. Examine how each line flows into the next, how the lines are distinct and yet together compose a cohesive, unified whole. Listen to great speeches. Listen to where the orators pause for effect, where their voice rises and falls. Ponder what makes certain sections electrifying and other parts captivating.

For more tips on being a great orator, listen to this episode of the AoM podcast:

Sources

Atgeld, John P. Oratory: Its Requirements and Rewards. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr and Co., 1901.

Buehler, E.C, and Richard L. Johannesen. Building the Contest Oration. New York: The H.W. Wilson Co., 1965.

Hardwicke, Henry. History of Oratory and Orators. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, The Knickerbocker Press, 1896.

Tags: Speeches