The Roman army hires a former legionnaire to hunt down a courier and intercept a letter he is carrying from the apostle Paul. But when this mercenary overtakes the courier, something happens that neither he nor the empire could have predicted.

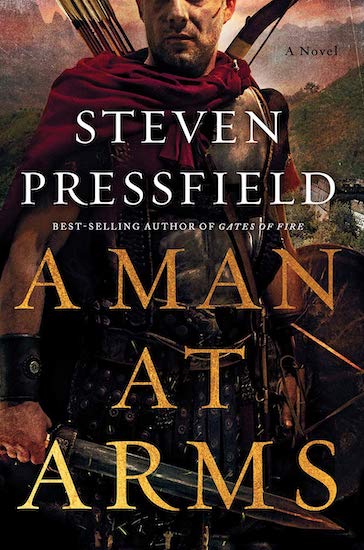

This is the plot of the latest novel from writer Steven Pressfield, entitled A Man at Arms. Pressfield is the author of numerous works of both fiction, including Gates of Fire and Tides of War, and non-fiction, including The War of Art and The Warrior Ethos. On today’s show, Steven explains why he decided to return to writing a novel set in the ancient world after a 13-year hiatus from doing so, and why he chose to center it around one of Paul’s epistles and the threat the Roman empire perceived in the growing movement of Christianity. We discuss how the protagonist of A Man at Arms, Telamon, embodies the archetype of the warrior and a philosophy of “dust and strife,” and yet has exhausted the archetype and is ready to integrate something else into it — a philosophy of love. Steven explains how the journey Telamon is on applies to all artists, entrepreneurs, and individuals, and the transition we all must make from the first half of life in which we’re discovering our gifts and honing our skills, to the second half of life, in which we figure out what those gifts and skills are for.

If reading this in an email, click the title of the post to listen to the show.

Show Highlights

- How did the idea for this book come about?

- What was the research process like for digging into early Christianity?

- Why is Telamon an un-aged character across Steven’s books?

- Telamon’s code

- What is the “dust and strife” way of life?

- Why does Telamon take on a mentee?

- Why every hero needs to save the cat

- The transition from mercenary values to a philosophy guided by love

- What does that philosophy really look like?

- Can the hero’s journey be taken out of order?

- Moving beyond the intellectual and rational way of living

Resources/Articles/People Mentioned in Podcast

- My first interview with Steven about the warrior ethos

- My second interview with Steven on overcoming the Resistance

- The Seasons of a Man’s Life

- Journeying From the First to the Second Half of Life

- Finding an Existential Second Wind

- The Quest for a Moral Life

- 21 Western Novels Every Man Should Read

- Seven Samurai

- Save the Cat

- Love Endures

- Love Is All You Need

- My interview with Richard Rohr

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

If you appreciate the full text transcript, please consider donating to AoM. It will help cover the costs of transcription and allow other to enjoy it. Thank you!

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. The Roman Army hires a former legionnaire to hunt down a courier, intercept the letter he’s carrying from the Apostle Paul. But when this mercenary overtakes the courier, something happens that neither he nor the empire could have predicted. This is the plot of the latest novel from writer Steven Pressfield, entitled A Man at Arms. Pressfield is the author of numerous works of both fiction, including Gates of Fire and the Tides of War, and non-fiction, including The War of Art and The Warrior Ethos.

On today’s show, Steven explains why he decided to return to writing a novel set in the ancient world after a 13-year hiatus from doing so, and why he chose to center around one of Paul’s epistles and the threat the Roman empire perceived in the growing movement of Christianity. We discuss how the protagonist of A Man at Arms, named Telamon, embodies the archetype of the warrior and a philosophy of dust and strife, and yet, has exhausted the archetype, and is ready to integrate something else into it, a philosophy of love. Steven explains how the journey Telamon is on applies to all artists, entrepreneurs and individuals, and the transition we all must make from the first half of life in which we’re discovering our gifts and honing our skills, to the second half of life, in which we figure out what those gifts and skills are for. After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/manatarms. Steven joins you now via clearcast.io.

Alright, Steven Pressfield, welcome back to the show.

Steven Pressfield: Hey, Brett, it’s a pleasure to be here, thanks for having me.

Brett McKay: So you got a new novel out, A Man at Arms. And what makes this novel unique, it’s your first novel set in the ancient world, so we’ve… I’m sure a lot of our listeners read Gates of Fire, The Virtues of War. This is your first novel set in the ancient world in over 13 years. So my first question is: Why has it been so long since you have written a book set in ancient Rome or ancient Greece? And what was it about this story that made you decide, “This is it, I gotta write another novel set in the ancient world”?

Steven Pressfield: Well, it’s a… I was having a coffee with a friend of mine about 13 years ago, whenever it was, another writer, and he was making fun of me. [chuckle] Well, he was saying, “How are you gonna kill the next person in your book? Are you going home to worry… Is it a spear, is it a sword? Is it, do you knife them?” Whatever it is. And I sorta got, I said to myself, “You know, maybe I’ve been too long in this area and I should get into the modern world a little bit.” So I decided, “Okay, I’m gonna shift and write stuff that’s more contemporary for a while,” ’cause I didn’t… I also didn’t wanna get sort of typecast as only being in the ancient world. But I missed it, and I missed the effects that you can produce when you use, let’s say more noble language that you can do when you’re writing in the ancient world. And I wanted to tell a story of this one character, Telamon, that’s a recurring character in three of my other books. And I was just… It takes a long time, Brett, to find a story, sometimes. You try and you try and try, you don’t… You just can’t find one. Then finally, a couple years ago, I did find it, and it was great fun to do a book that was only about this one character, a favorite character of mine, Telamon, and also, to get back into the ancient world.

Brett McKay: Well, so how do… The basic story is that Telamon, he’s a former Roman legionnaire, and this is around the time when the early Christian movement was just starting.

Steven Pressfield: Right.

Brett McKay: And he decides to team up… That’s how it ends up, but teaming up with some Christian messengers who were carrying epistles for the Apostle Paul. How did, where did that come from? That’s just, it seems out of left field.

Steven Pressfield: It’s a… The long backstory is my niece got married a couple of years ago, and she asked me to be the officiant at the ceremony. Actually, my brother had already secretly married them and I was gonna be the public face of this. So I went to the Book of Common Prayer to try to find, put together my own little traditional type of whatever you wanted to call it, a service, whatever. And everything that I fell in love with came out of Paul’s letter to the Corinthians, 1 Corinthians, “Through, we see through a glass darkly, and faith, hope and charity,” and all those wonderful, great quotes. And that just sorta stuck in my mind. And things percolate, and as a writer, you’re always looking for some hook to hang a story on, and I thought, “This is a great thing. This letter, that it actually was a real letter that had to be delivered, and that the Romans were trying to stop it.” And they made perfect bad guys for a kind of an action chase story that would have real depth to it, that would really be about things on the soul level, and not just on the action level. So that’s how the story came together, Brett.

Brett McKay: And I’m curious, how’d you go about researching the book? Because writing about Christianity can be tricky ’cause it’s so part of our culture. If you grew up in the West, you know the story, basically. So it’s hard to get at it in a different angle. But what I liked about reading the Man at Arms is that oftentimes, I felt like I wasn’t reading a book about Christianity. I was like reading a work of political fiction where I was… I’m able to see how the Romans or even the Jews looked at or viewed this early movement. So first, how did you research that? And was that what you’re trying to convey? You’re trying to look at the Christian movement from a different perspective?

Steven Pressfield: Yes, I certainly do not consider this a book about Christianity, by any means. If anything, I would say it was a kind of a political thriller or an action story. It really is more about the movement of early Christianity as seen through the eyes of Rome, of the Empire of Rome, and as seen as a threat, as something that they have to deal with, which it really was. And rather than, until the very end of the story, which I don’t wanna give anything away, only then does it really get into the spiritual aspects. But I definitely felt like I was selling a political story of a movement that was a threat to an empire, and the empire’s moves to crush that movement.

Brett McKay: And can you give us a taste of what that world looked like, the way you describe in your book?

Steven Pressfield: Well, one of the things that I thought was really interesting was that early Christianity was a threat not just to the Roman Empire, but to the Jewish community, to the Kingdom of Israel at the time, Judea, because it threatened to split and weaken the Jewish community under… Which was under tremendous oppression from Rome, and needed to be as united as it possibly could. So that there were a number of elements, bad guys, trying to stop this growing faith. And at that time, the story is set maybe 20 years after the crucifixion, so it’s really about the primary engine of fledgling Christianity at this point, was the Apostle Paul, who was sort of the, I don’t know, the paramount proselytizer, the paramount push behind expanding it into the various communities around the world.

Brett McKay: And I like the way you described that from the Roman perspective. Oftentimes, the generals, when they talked about the Christians, they didn’t even call them Christians; they just called them the Messianic Jews. They were just a crazy branch of Judaism.

Steven Pressfield: Yes, yes ’cause I think that’s exactly what it was. It wasn’t thought of as this new thing called Christianity; it was just sort of these crazy Jews, this crazy offshoot of Jews that believed in another world, and that had tremendous faith, and that really had the type of belief and the type of passion that could threaten an empire.

Brett McKay: What was threatening about it? Can they just be like, “Well, these are kinda wackadoos, just ignore them.” What do you think the threat was?

Steven Pressfield: Well, the threat was that it was so expansionist that its home was really not in this world. Its home was in the Kingdom of Heaven, and so anybody that… You can see it in passionate movements today, too, where someone or the group, the collective breaks mentally and emotionally, breaks out of the concerns of the material world and is concerned with another world, a world beyond this world and so, is willing to undergo sacrifices and give up their lives, and etcetera, etcetera.

And also, at the time, I think early Christianity, among the people who were following it, was an absolute sensation in terms of the passion that it aroused. And I think that Rome felt, and I say this in the book, I put this in the mouths of one of the tribunes, that the emperor’s sleep was not troubled by other armies, but rather a new faith, something that people could believe in beyond this world; that was a real threat. And in fact, that’s what did bring down the Roman Empire, so that the Vatican is now in Rome, right? It became the seat of Christianity, very heart of the empire.

Brett McKay: And the other, if you think about the Christian movement, they were using the empire to further their aims. Paul, they were able to, they’re able to… The reason why Paul is able to connect with all these different groups ’cause Rome, the empire built all these roads and shipping lines, and they were using that to spread their message.

Steven Pressfield: Yes, that was a delicious irony of the thing, that the very modern inventions that Rome had brought, see the roads that they built, the mail, this was what the apostle used to further his message and get it out there. So Rome was complicit in its own demise, in that sense.

Brett McKay: Well, let’s talk about Telamon. So you mentioned this was a character from previous books. What other books did he make an appearance in?

Steven Pressfield: He was in Tides of War, which was set during the Peloponnesian War. Then he came back unchanged and un-aged 100 years later as a mentor to Alexander in my book, The Virtues of War. And then I even set him at… I gave him a cameo in a book called The Profession that’s actually set in our contemporary future, about 20 years in the future, but that was a little tiny thing. But he was in two books where 70, 80 years apart, where he had not aged a day. And then in this new one, in A Man at Arms, it’s another few hundred years later, and he hasn’t aged a day either.

Brett McKay: And what’s going on, though? What do you… I think that’s interesting, you’d have a character who’s the same guy, but he just, he shows up in different time periods.

Steven Pressfield: To me, this… Brett, it’s kind of interesting because this is, it’s nothing I particularly planned. I didn’t say, “Oh, I’m gonna have this character in one book and again and again.” But once I sort of started doing that, it seemed to really make great sense to me. To me, Telamon is sort of the supreme archetype of the warrior. But he is also the universal soldier in the sense that he appears in century after century unchanged, just like war is a universal constant in the human race, and warriors don’t change, either. So he is one of these, he’s the universal soldier to me who appears over and over again. And of course, the next question is: Why? Did he commit some terrible crime in the past that he has to pay for by doing this? And I don’t even know the answer to that. But I just see him as stuck in this archetype and sort of condemned to live it over and over.

Brett McKay: And what’s interesting about Telamon in this, in A Man at Arms is that okay, he’s a former legionnaire. And in the Roman army, they’re, a legionnaire, you had a career. You serve a certain amount of time, then you got some land, you basically are able to take it easy. But he doesn’t do that once his service is up. He decides to become a mercenary. What do you think is going on there? Why didn’t he follow… Is it just ’cause he’s that archetypical warrior, he has to keep fighting?

Steven Pressfield: I think that’s exactly it, that his… As he says in A Man at Arms, he was in the legions, but he was not of them. And that he never really, he never embraced the eagle or the idea of Roman citizenship, or the three-part name that Romans always took, or that… People might volunteer for legions in Spain, let’s say, or in Gaul, they would not be Romans, they would be natives of that country. And they would, in essence, take on a Roman identity. They would change their name like in the French Foreign Legion, and they would take a Roman name, and they would achieve Roman citizenship, and they would essentially be full Romans or artificial Romans. And in their mind, of course, they were full-fledged Romans. And then they would go through their service, and as you said, they’d get maybe some land or they would have various bounties that they achieved over time and have some money.

But Telamon is a guy who, from the previous two books of mine, is beyond all that. He doesn’t care who he serves for. He doesn’t care what the flag is. He is a… His goddess, the only goddess he worships is Aries, the Greek goddess of strife. And he is one of these guys who is a rare bird that he said, as he says, “I fight for the fight alone, I serve for the serving alone, I tramp for the tramping alone.” So he was definitely not a part of the legions in any emotional way. He was beyond that in his own mind. So when he got out, it was never a question that he would settle down and have a farm. He’s continuing to serve the god of strife and moving on in his own way as a solitary individual. To me, he’s kinda like a samurai that you see in the rōnin movies where they were masterless samurai that were cut loose from the collective, and were just on their own, like a western gunslinger in an American Western.

Brett McKay: Yeah, or he’s like a private eye, he’s like a Humphrey Bogart type. He has his own code; it’s not the code of the state, but he’s got his own code that he’s gonna follow no matter what.

Steven Pressfield: Exactly, which is what makes him so interesting to me, and what makes him, I think, a very modern character. He’s like a private eye, he’s like a Clint Eastwood man with no name type of gunslinger. He’s like the Humphrey Bogart character in Casablanca, an individual who has cut himself free from any collective beliefs, any flag, any cause, any leader. And he’s trying to navigate his way just as an individual by his own code, which is constantly evolving as he has his various adventures.

Brett McKay: And as you said, it’s primarily, like he’s just drawn to fighting. He calls it, his philosophy is dust and strife. And as I was reading this, it’s hard not to bring in some of the other stuff you’ve written about in your non-fiction about being an artist, being a writer, being a business person, entrepreneur. Do you see any connection there? What you’ve written about in, say like The War of Art to Telamon’s dust-and-strife anti-hero philosophy?

Steven Pressfield: Yes. [chuckle] Yes, absolutely. I always, I feel like I have sort of two types of books that I write. [chuckle] One is a kind of a inner war type of book like The War of Art that’s really about the mental and emotional world that an artist or an entrepreneur deals with. And the other are these novels that are usually set in the ancient world and they’re about the outer war, where the warfare becomes a metaphor, external warfare becomes a metaphor for the internal war.

And one of the things that’s really interesting to me about the character of Telamon is that he is fighting both. He is a physical warrior for whom violence is a way of life, but he’s also a philosopher, and he’s trying to fight his own internal wall. This, as strong a character as he is as a warrior, he feels frustrated in that. He’s like up against the wall, like he’s exhausted that archetype. And much like, say the Humphrey Bogart character in Casablanca, or the Clint Eastwood character in various westerns, or a lot of samurais. They can do their thing, they can win these fights, they can endure adversity, but they know in their hearts that something is missing, that they’re stuck. And this story, like Westerns or like samurai movies, is about bringing the warrior beyond that to the next level, which involves a step into love. And that’s where the the Apostle Paul’s letter comes into this whole story.

Brett McKay: In tying this back into your work with artists and entrepreneurs, do you see a lot of artists and entrepreneurs, like that’s their philosophy? They take that sort of dust-and-strife philosophy when they first start out?

Steven Pressfield: I think absolutely, and I think that you almost have to. If you’re an entrepreneur and you’re launching a new business or a start-up or something, or if you’re an artist and you’re writing a book or a movie, or you’re a musician, or whatever, you’re alone, and the world is a hard, cruel world. And if you’re gonna break through that world, you have to have an aggressive mindset, a warrior mindset. And it’s also very much of an eagle ego mindset, it’s really an us-against-the-world-type of environment system or mindset just to break through. But once you do break through, once you have established yourself somewhere, then the next question becomes: What am I gonna do with this identity that I have, with this platform that I’ve achieved? Am I just… Is it just about my own ego and pushing forward for more money or whatever? Or is it actually about something? Do I really have some gift that I wanna give to the world or some message that I’d like to bring?

Brett McKay: And one of the ways you flesh out the character of Telamon is he has an apprentice… Or and I’d say like I don’t… Telamon is the kind of guy like he’s a lone gun, so of course, he wouldn’t want an apprentice, but so rather this kid basically decided, “Telamon, you’re gonna be my mentor, whether you like it or not.” Tell us about this boy, and like what can we learn about Telamon because of the boy’s like attract… Like him wanting to be mentored by Telamon.

Steven Pressfield: That’s a great question, Brett. And this was almost an instinctive choice as a writer. I had the character of Telamon, and something made me say to myself, he needs an apprentice, he needs somebody that idolizes him, and also somebody that we can see the story through his eyes. And I was thinking… Have you seen the movie Seven Samurai?

Brett McKay: Yes.

Steven Pressfield: You know, the lead samurai at the very start of the movie has a young samurai attach himself to him. Do you remember that character?

Brett McKay: Right, right. Who goes all the way through that he… He bows down to him, he says, “Please, sir, make me your apprentice, I wanna learn from you.” And I thought that that was just a great way of getting into Telamon’s character, because the way he teaches the apprentice is he never says anything, he just allows him to watch, or he says very few things. And of course, what was clear to me as a writer was that in the end, it was gonna be the apprentice who winds up teaching the master and that things would turn by the end. So that was the reason for the character of David, the young boy who follows Telamon.

And, to give you some context, David, he comes from, I guess, a really religious… His religion, Jewish family, so what… Going the warrior path was like, ‘Yeah, that’s not what you’re supposed to do’, but he still wanted to do that.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah, he was definitely some… He came from an impoverished family, he’s illiterate, but very much felt the oppression of the Roman Empire on them, and very much felt that the Jewish community as it stood at that time was not strong enough to resist this thing. And so he himself, just kind of seeking manhood, seeking masculinity, if you wanna use that word, which I do, sought out the most masculine character that he could find and attached himself to him, ’cause he wanted to learn to stand up for himself and to stand up for the community.

Brett McKay: And Telamon, he could have just told this kid to take a hike or even killed him, like, “God, you’re just annoying me,” but he doesn’t. Why do you think that is? Have you figured that out or is it… Was Telamon just opening himself up to change or… What do you think?

Steven Pressfield: That’s a great question, Brett. It’s sort of like… Have you ever read a book called Save the Cat?

Brett McKay: I have not.

Steven Pressfield: By Blake Snyder. It’s a wonderful book. There’s like three or four of these books. It’s about screenwriting, it’s about writing movies, and Blake Snyder is a screenwriter, or was, he died tragically at a young age, but one of the things that… The idea behind Save the Cat is that any hero in a story needs to do something early in the story that makes us in the audience think that he’s a good guy or a good gal, and the Save the Cat is Blake Snyder’s way of doing that. The hero should save a cat or something like that, do something nice, because most heroes in stories, if you think about gunslingers or samurais or private eyes or any of these kind of classic hard-bitten heroes, most of them are really tough hombres, they’re just hard to like. And a lot of them, violence is their first gesture in anything, their first option. So to let us, the viewer, into the story, you sort of need to have a little bit of a something that shows, “Ah, this guy has a little bit of a soft spot anywhere.”

But also more important than that I knew with Telamon, at the start of the story, that he was gonna seem to be the all-time hardcore badass guy, but by the end of the story, he was going to have switch and come all the way over to a position of love. So I wanted along the way, for us to see that even beneath his crusty hard exterior, he does have compassion and he can feel for somebody and take on this young boy… To do that was really a real gesture of empathy and a real kind gesture, and I think that made a lot of sense that that would then come out later in the story as we got to know Telamon completely.

Brett McKay: I’m curious, in your own life, have there been situations where you were David, the boy, looking for that mentor, or when you were Telamon, and you’ve had a young person like, “Show me the ways.” Have you experienced that personally?

Steven Pressfield: That’s another great question, Brett. I definitely have had both, and if I would say one was more predominant it’s that I’ve had mentors, and I’ve had many mentors where I was in the position of being the apprentice, and that had been absolutely invaluable to me, could not have done anything that I’ve done without them. So yeah, I think that’s a huge part of our evolution. I’m sure it’s true for you too, that you find yourself taking people under your wing from time to time, and also reaching out to mentors that can guide you and give you some feedback along the journey that we’re all on.

Brett McKay: Did you have a mentor that stood out to you that was really kind of that Telamon, really crusty and grouchy, but you learned a lot from them?

Steven Pressfield: I’ve had many, but I’ll tell you one. In my 20s, I drove trucks for a while, and I had a mentor, a guy named Hugh Reeves, who was a dispatcher at this trucking company in North Carolina that I worked for, and he took me in when he had no real reason to do so. I was really clearly kind of lost in my own weird journey, and there was one moment that he… That was… Really made a pretty deep impression on me, I was on my own sort of hero’s journey, my own odyssey, I was lost, whatever, and I kept screwing up. I would deliver loads late and I would get into accidents and stuff like that. And at one point Hugh called me into his office and he sat me down and he said, “Son, I don’t know what sort of journey you’re on in your own mind here, but this is a business. We are in business here and you are a representative of this business. Our job is to deliver loads and deliver them on time and not to screw up, and you cannot afford to be going through whatever emotional stuff you are in your head. You gotta get it together, because this is a business designed to make money.” And that was like one of those moments of a slap in the face, “thanks, I needed that” type of thing. So he was a great mentor to me, and I’m grateful to him to this day.

Brett McKay: Oh yeah, he taught you how to be professional. Gotta be a professional.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah, he certainly gave me that idea, anyway. It took me a long, long time to actually become a professional.

Brett McKay: Alright, so Telamon, former legionnaire, he gets basically voluntold by the Roman army to hunt down a courier who’s carrying a letter from the Apostle Paul, because again, the Romans are freaking out that this movement is gonna spread and bring down the Empire. He meets the courier, and instead of turning the courier in, he has some sort of conversion and we’re not gonna talk about what that conversion looked like, that’s the book, that’s… We don’t wanna… We don’t wanna do that, but I’d like to use that, his conversion, whatever that is, as a starting off point to discuss that… What you’re talking about, that switch from mercenary values, that philosophy of strife and dust, to a philosophy guided by love. What is… For you, what does that… What does a philosophy guided by love look like in an artist’s life or a business person’s life or just a man’s life, and I’m guessing does Telamon completely leave this philosophy of strife and dust behind and embrace this love philosophy?

Steven Pressfield: He doesn’t really. I think he integrates it, and there’s a character that is central to this that we haven’t mentioned, and it’s a young girl who is a nine-year-old mute feral girl, who is the daughter, or at least we think she’s the daughter of this suspected courier that’s carrying the letter. We don’t know where the letter is, it’s all a mystery. And a bond begins to form between Telamon and this girl, and it’s sort of a mysterious bond that they just seemed to be simpatico with each other, and in essence, she proves to be, of all the warriors in the story, and there’s a bunch of them, she is sort of the supreme warrior of in terms of dedication and of ability to rise to an occasion. And so what happens with him, without giving away too much of the story of Telamon, is that he finds his heart opening to this girl, sort of like it did to David, to the boy who he takes on as his apprentice. And the story as it goes along, this girl kind of proves herself over and over to him in one way or another, and he begins to not so much care for any message or any spiritual doctrine as he cares for her, and that’s kind of what… Where love kind of enters the picture, but he remains a warrior throughout the whole thing, and his warrior skills are set in the service of this love.

And when the Apostle Paul talks about love in his letter to the Corinthians, he’s not really talking about romantic love or the love that we feel for a brother, or the love that we feel for a wife or for our family, he’s talking about true Christian love at the highest level; love for the entire human race, and for anyone who was is suffering, anyone who is vulnerable and love for the kingdom of heaven, the highest form of love, agape really in Greek, all these elements of come together as the story progresses, the letter, the girl, the bad guys, etcetera.

Brett McKay: Well, let’s tie it back into your previous non-fiction writing. Have you seen this sort of theme play out in your non-fiction writing as well?

Steven Pressfield: Yes, I think that what… If we ask ourselves, let’s say we wanna be a writer, or we wanna be an entrepreneur, or we wanna be a songwriter, or a filmmaker, or whatever, the first step is to learn how to do that, to be a professional at that, to acquire those skills. But the next step, sort of the second half of our adventure is what are we gonna use those skills for? What… And in essence, if we think about… This is maybe getting a little too deep, Brett, but what the hell.

Brett McKay: Let’s do it.

Steven Pressfield: If you think about the hero’s journey in the Joseph Campbell sense, which is kind of a self-initiation that an individual goes through through whatever suffering they have or whatever journeys they undergo, it always ends kind of like Odysseus coming back home to Ithaca. It always ends with a return home, kind of like Dorothy comes back to Kansas, or any heroes returns to where they started, but they return as a different person, and they return… This is according to the legend, with “a gift for the people,” which comes from what they’ve learned on this journey, what their solitary suffering has brought them to.

So the question then becomes, if you’re an entrepreneur, if you’re an artist or whatever, what is my gift? That’s the question that we all have to ask ourselves, What… If you’re writing, you say, “Well, what kind of books was I put here to write?” If you’re a songwriter, you say, “What kind of music was I put here to produce?” And when you get to that, the question really is, it’s really a gift for the world, it’s a gift for others. Whatever your… The song you’re writing is meant maybe to bring somebody up from a depressed place, maybe to tell them that they’re not alone in a situation, a broken heart or a frustrated life, whatever, but it is a gift, and it’s a gift that’s given out of love and that’s… I believe that is the whole meaning of our existence on this planet, that we kind of start off as children, as infants, where it’s all me, me, me, give me my food, whatever. And even as we become adults, it’s still a kind of a me, me, me thing. I wanna achieve my goals, I wanna make money, I wanna establish an identity, I wanna have a family.

But at some point, the question becomes, “What am I doing all this for?” And the answer, if we’re going to evolve and not be stuck in some case of arrested development, is that we’re giving something from our heart to the rest of the world. And if you’re an artist, that’s your art, that’s your books, that’s your music, whatever; if you’re an entrepreneur, it’s whatever business that you’re putting forward. So I think that’s how, if we are gonna evolve, we evolve from fear to love or from ego to love.

Brett McKay: No, I like this ’cause this ties in nicely with some other guests we’ve had on the podcast, like David Brooks has that book, The Second Mountain, and then there’s Richard Rohr, he’s this Franciscan monk.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah, Richard Rohr, yeah, David Brooks too, you’re absolutely right. Those are definitely guys that I am tuned into and I read all their stuff.

Brett McKay: Right, so this idea is first you… The first part of life is like you’re there to construct yourself, and it’s very practical hands-on, so what you’re talking about, you have to learn your craft, learn how to be a good writer, be a professional. And then at a certain point, you have to figure out, well, what’s this for. And I’m curious, what do you think happens if you reverse those? What if you try to get that more higher level idea first before getting the practical level? What happens if you are Telamon who’s guided by love before you are Telamon, the mercenary man at arms?

Steven Pressfield: That’s a great question. I’m not sure I really have a real answer to that. I’ve never even thought about it. What were you gonna say Brett?

Brett McKay: I don’t know either. I was thinking as I was… As you were just talking. I was like, “What have you flipped the script?”

Steven Pressfield: It seems to be unnatural to do that, in that I don’t know if that actually would work. I think sometimes someone at a young age might think that they are doing something purely out of love, but I’m not… I would be skeptical if I met that person, not to say that it doesn’t happen or it isn’t true, but I really don’t know what the answer to that is, it just doesn’t seem like things work that way.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I’m just riffing off the cuff here. It probably would be ineffective, ’cause you wouldn’t have the skills. You have this idea of what you want and what… But you don’t have any skills to make it come to pass, to make it manifest itself, and so you just become… You’re sort of impotent in a way.

Steven Pressfield: Or even I would say beyond the idea of skill. I mean, I have a theory. In one of my books, one of my non-fiction books, I’m sure you know about it, it’s called The Artist’s Journey, and the theory of the… The thesis of that book is that we have… It’s kind of like Richard Rohr, first half of life and second half of life where that we have two lives, and the first is our hero’s journey. And when that’s done, we go to our artist’s journey, which is just like what Richard Rohr says, first, you establish the vessel that is yourself, and in the second half, you ask yourself, “Oh, well, what do I fill the vessel with?” But going back, what I meant to say was, in that first half of life, in that hero’s journey, it’s not just about the acquisition of skills, I don’t think. I think it’s also about a humbling, a deep humbling that happens to us. I think almost always the hero’s journey ends with or hits a point of what they would call in Hollywood an all-is-lost moment, a moment where we really hit bottom, and then turn around from there. And it seems to me, if we… Going back to the Apostle Paul, it’s the moment of his conversion on the road to Damascus.

But… So in other words, I think the first half of life is not just about acquisition of skills, but it’s about being broken. It’s about coming to a place where we say, from our ego, “I can’t handle it. My ego is not enough. Living out of the rational mind, out of the ego is not enough.” And we, at that point, and this becomes kind of religious, or at least spiritual, we surrender, we give up. If the analogy would be to say an alcoholic, they would say, “In that moment that I have no control over alcohol and I have to call on a higher power, I give up, I can’t do this by myself.”

So that, I think the key to that is that once we’re humbled in that way, then we’re truly capable of love, then we have empathy, not just for ourselves, because we’ve been broken and we’ve seen how broken we can be, but it immediately applies to others. And we start to have compassion, “Well, if I can fall apart like I’ve fallen apart, or if I’ve seen in my deepest self and I see how broken I am, then everybody else is on that same path, and my only real honorable way of dealing with others is with compassion and empathy and to try to help.” And that’s love. So I don’t mean to get too deep here Brett, but I think that’s what it’s about.

Brett McKay: And then you see that play out with Telamon. He has a moment where he’s broken.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah, definitely. He has that moment. Yes.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and then also what I liked about the way you do with the book is you show how that figuring out that second half of life stuff typically happens. And again, I don’t wanna give it away, you gotta read in the papers, if you wanna see how that happens. But it’s not the way people typically think it happens, it’s not intellectual, it’s not rational, it’s something else.

Steven Pressfield: No, it’s definitely not, it’s definitely happening on the soul level and not on the behavioral level or the psychological level for all of us, when we come to that change. And if you think of a lot of stories have that same pattern, books or movies, where the hero hits a point of no… A dead end. If… I’m thinking of a movie, Cool Hand Luke, I don’t know if you remember that, with Paul Newman.

Brett McKay: Oh, yeah, of course.

Steven Pressfield: Where he’s on the chain gang ride and they finally break him, where he hits that moment where things turn around for him. So it’s a common, I think, for all of us.

Brett McKay: And I’m curious, have you already thought about like what happens to Telamon next, did he escape this eternal recurrence of being a warrior?

Steven Pressfield: No, I haven’t. In fact, I know I’ve got to but I’m kind of scared to death of it. I know I haven’t taken it all the way yet, so I’m waiting for the muse to touch down and help me on that one.

Brett McKay: Well Steven, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book and your work?

Steven Pressfield: Just my website, which is just my name, Steven Pressfield with a Steven with a V, and that’s got all of the various stuff about it, but the book is on sale at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, bookstores, indies, everywhere.

Brett McKay: Alright, well, Steven Pressfield, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Steven Pressfield: Hey, Brett, thank you very much. I’d do it again any time on any subject.

Brett McKay: Alright, thank you. My guest today was Steven Pressfield, he’s the author of the book, A Man at Arms, available on Amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find out more information about his work at his website StevenPressfield.com. Also check out our show notes at AOM.is/ManAtArms, where you can find links to resources where he delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of The AoM podcast. Check out out website at Artofmanliness.com, where you can find our podcast archives as well as thousands of articles written over the years. And if you’d like to enjoy ad-free episodes of the AoM podcast, you can do so on Stitcher Premium. Head over to Stitcher Premium, sign up, use code MANLINESS at checkout for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the Stitcher app on Android or IOS and you can start enjoying ad-free episodes of The AoM podcast. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate it if you take one minute to give us a review on Apple Podcasts or Stitcher, it helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you.

Please consider sharing the show with a friend or a family member who you would think would get something out of it. As always, thank you for you continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay reminding you all to not only listen to the AoM podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.