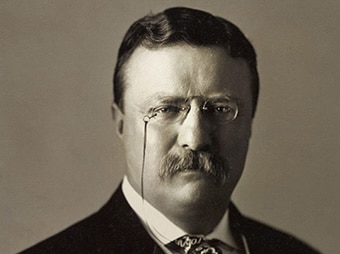

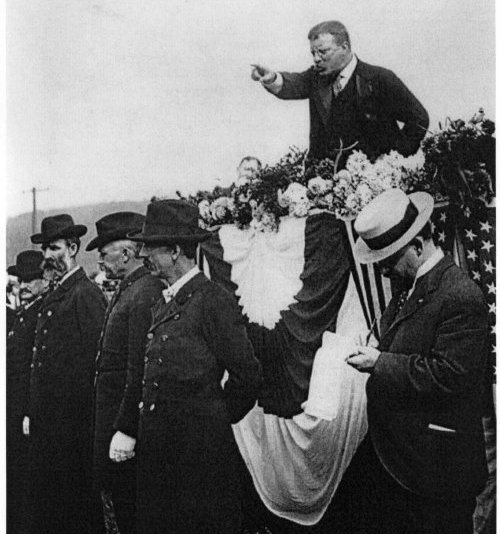

If you’ve been following The Art of Manliness for awhile, you know we’re big fans of Theodore Roosevelt. The man embodied the Strenuous Life. He was a rancher, a soldier, a hunter, a statesman, and a practitioner of boxing and judo. But what many people don’t know about Roosevelt was that he was also an accomplished man of letters. He wrote over forty books himself and read thousands of others over the course of his lifetime. And as my guests on the show point out, TR’s literary life was tightly interwoven with his mighty deeds.

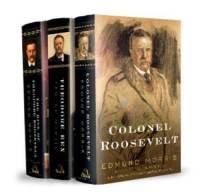

Today on the show, historians (and husband and wife team) Thomas Bailey and Katherine Joslin discuss their book Theodore Roosevelt: A Literary Life. We discuss how Roosevelt began the writing habit as a 7-year-old boy and how he wrote one of America’s greatest military histories when he was just 24 years old. We then discuss TR’s greatest literary successes, including The Rough Riders, The Winning of the West, and African Game Trails. Thomas and Katherine share how Roosevelt’s penchant for action influenced his writing and how his writing inspired him to take action, and how John Wayne and Western movies wouldn’t exist without TR’s literary work.

We then get into Roosevelt’s reading habits, including his opinion of compiling lists of must-read books.

You’re going to gain new insights about one of America’s larger-than-life characters listening to this show.

Show Highlights

- Why TR is overlooked as one of the great American writers

- When did he start showing a penchant for writing?

- How TR’s reading as a child influenced his Romantic outlook

- What was his guiding ethos with his writing?

- Roosevelt’s relationship with language and his writing process

- Did Roosevelt have an influence on the literary scene in America?

- Why Roosevelt paved the way for John Wayne

- TR’s most famous book and how much he actually made for his writing

- Roosevelt’s voracious reading life

- A few books Roosevelt didn’t like (which wasn’t many)

- What Roosevelt thought about education and autodidactic, lifelong learning

- How his reading as an adult influenced his policy ideas and political decisions

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- The Field Notes of Theodore Roosevelt

- TR’s Rules for Reading

- The Library of Theodore Roosevelt

- Quentin Durward by Walter Scott

- Theodore Roosevelt Center

- The Naval War of 1812

- The Rough Riders

- The Battle of Plattsburgh

- How to Speed Read Like TR

- The Man in the Arena

- The River of Doubt by Candice Millard

- 21 Western Novels Every Man Should Read

- Lonesome Dove by Larry McMurtry

- Why and How to Become a Lifelong Learner

- The Jungle by Upton Sinclair

- Strong as a Bull Moose

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Citizen. Their Promaster collection makes watches for men who push their boundaries. And, with Citizen’s Echo Drive technology, your watch is powered by ANY light and will never need a battery. Go to CitizenWatch.com/podcast to learn more.

The Great Courses Plus. Better yourself this year by learning new things. I’m doing that by watching and listening to The Great Courses Plus. Get one month free by visiting thegreatcoursesplus.com/manliness.

Michelin. Whether your tires are new or worn, you should have the confidence to get where you need to be. That’s why Michelin designed the MICHELIN Premier tires, with worn performance in mind. Visit michelinman.com/longlastingperformance for more info.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Recorded with ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. If you’ve been following The Art of Manliness for a while, you know we’re big fans of Theodore Roosevelt. The man embodied the strenuous life. He was a rancher, a soldier, a hunter, a statesman, and a practitioner of boxing and judo, but what many people don’t know about Roosevelt was that he was also an accomplished man of letters. He wrote over 40 books himself and read thousands of others over the course of his lifetime, and as my guests on the show point out, TR’s literary life was tightly interwoven with his mighty deeds.

Today on the show, historians and husband and wife team, Thomas Bailey and Katherine Joslin discuss their book, Theodore Roosevelt: A Literary Life. We discuss how Roosevelt began the writing habit as a seven year old boy and how he wrote one of America’s greatest military histories when he was just 24 years old.

We then discuss TR’s great literary successes, including The Rough Riders, The Winning of the West, and African Game Trails. Thomas and Katherine share how Roosevelt’s pension for action influenced his writing and how his writing inspired him to take action and how John Wayne and western movies wouldn’t exist without TR’s literary work.

We then get into TR’s reading habits, including his opinion on compiling a list of must read books. You’re going to gain new insights about one of America’s larger than life characters listening to the show. After it’s over, check out the show notes at AOM.is/TRwriter.

Tom Bailey, Katherine Joslin, welcome to the show.

Katherine Joslin: Thanks for having us.

Thomas Bailey: Thanks for having us. We’re glad to be here.

Brett McKay: You two collaborated on an intellectual biography of Teddy Roosevelt. There’s been so many biographies written about him. You guys wrote just, it’s a very thorough long biography just about what he wrote and what he read. One of the main takeaways I got from your book is that Roosevelt is often overlooked as one of the great American writers. Why do you think that has happened to him? He’s written over four dozen books, and on top of that, he wrote all these magazine articles. Why has he been overlooked amongst American writers?

Katherine Joslin: I think it’s overwhelmed by his political presence because he is that major figure of that 20th century. I think we’re thrilled and captivated by the myth of him. It’s not that his writing’s been abandoned quite, but I think it’s ripe for the picking now for people to go back and read it, especially people who admire him as much as your listeners do.

Brett McKay: Okay. Let’s talk about when his writing career began. When did Roosevelt start showing a penchant for writing? Was it a very early age?

Katherine Joslin: Oh. He started writing as soon as he could pick up a pencil, and he wrote. He wrote letters. He wrote journals. I worked on the early Ted. He’s such a wonderful character right from the start. When he would write letters, he’d write a different kind of letter to his father, a different one to his mother, a different one to his siblings.

He then wrote these journals about what he was doing and he wrote them almost like plays and his siblings all were characters in it. You don’t even know quite who he was writing for. He was writing at seven and at nine, these very early ages. Maybe he was writing for us.

Thomas Bailey: He was fascinated by reading at the same time. The Roosevelt children were home schooled and they were given free reign of the library and free reign of the New York Public Library, and they simply read and read and read. They read classic novels. They read boy’s stories. They read stories for little girls. They read everything. He was completely fascinated by the world of language and he always was until pretty much the very day he died. He was still writing and reading.

Katherine Joslin: I just want to add that as I was reading through this journals and such, they were reading things as children, like the Mayne Reid or John James Audubon and certainly Longfellow and Sir Walter Scott and Dickens and such, but he was also reading with his sisters books like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Little Pussy Willow where she talks about how we all want to grow up to be good girls, and Louisa May Alcott’s An Old-Fashioned Girl. He grew up without prejudice about writing. He read anything he could get his hands on. He always did all his life.

Brett McKay: I’m curious. Do you think his reading as a young child influenced his, I don’t know, his romantic view towards life later on that we would see in his speeches about … He was a jingoist. He glamorized war. He was all about the outdoors. Did his reading as a child influence that?

Thomas Bailey: Well, I think it probably did. He loved the novels of Sir Walter Scott, which are pretty intensely romantic, and his favorite boy, don’t forget, was named Quentin for Scott’s novel, Quentin Durward, which is one of his most romantic and intensely romantic medieval novels that was written in the middle of Scott’s career. He adored that novel and he adored Quentin. Yes, I suppose that his intense romanticism partly grows out of his reading, but it also grows out of his nationalism and it grows out of his intense love of the outdoors.

Brett McKay: As a child, Tom, going back to your interest in nature writing, as a child, he thought of himself as a natural historian. He felt he was doing good work. He wrote about birds and animals and his area. His career as a naturalist began as an eight year old or a nine year old.

Katherine Joslin: That’s right. I did the early kid, so I can jump in here. He meant to be ornithologist and he was near-sighted and the family didn’t know it until he was 14, so he would go out and listen to birdsong and there are these wonderful descriptions where he’s not very musical, but he tries to get the music right, and then he spends a lot of time.

He’s supposed to be a kind of manic kid, but he spends hours just observing and then writing intricate notes about the bird. Of course, then he’d kill the bird and slit it open and he’d measure everything, but he meant to be a scientist. When he went to Harvard, he had hoped to do that, but didn’t turn out that way.

Thomas Bailey: He found when he got to Harvard that under the influence of Louis Adiziz, the science at Harvard had become science of the laboratory, and he wanted to do science out in the woods. When he was a kid, he was extraordinarily patient along with his hyperactivity, of course, and his sketches of the mice and the birds and the things that he saw in the natural world are really touching in their emotional intensity and their skill. He was quite a wonderful sketcher.

Pretty much, we could say this for sure about Roosevelt in all of his guises, whatever he turned his head to, he did very well. He turned his head to an awful lot of things, not just writing and drawing and reading, but all kinds of other things, as well, as you and your listeners well know.

Brett McKay: Sure. I’m curious, is there someplace people can go online to see his journals from when he was seven or nine years old?

Katherine Joslin: Well, what’s interesting about working with a figure like Theodore Roosevelt is everybody wants to read him. When we started to work, we were working at Harvard and we were working with things that weren’t online, but now there’s a Theodore Roosevelt Center. They’re looking to put all of this stuff that we were looking at in a privileged way is now in a democratic way available to your listeners, that’s right. You can pretty much call up all of this, or not everything, but the childhood material is available. It’s available at Harvard too, but also at the Dickinson State site.

Thomas Bailey: Right. Well, it’s not all digitalized yet because there’s way too much to digitalize very fast, but it’s coming online gradually and it’s coming online steadily and it’s a fully funded research program. Within probably a decade, all of his writings, well, all of them, the letters, the journals, the articles, everything, will be available online and it’ll be a wonderful national treasure.

Brett McKay: As a child, Roosevelt started writing journals, letters, rudimentary scientific papers about natural history or the environment. What was Roosevelt’s first big breakthrough as a professional writer? When did that happen?

Katherine Joslin: The breakthrough, the really breakthrough book is Rough Riders, and that comes later. After he left college, he was studying for law, and he was working on two pieces of writing. One is a hunting story called South South Southerly. That’s the name of the ducks that he was hunting, and they very nearly died in the hunt. If he had developed that part of himself, that more creative part, he probably would be a very different writer today.

You can see elements of that writing as you move through his career, but then he got a hold of his naval war of 1812 and he wanted to be an historian. Remember that after he was president of the United States, he was president of the American Historical Association, so he wanted to be known as an historian.

He worked on this naval war, which was really about the battle between the United States and Britain in the Great Lakes, and then they wind up in Plattsburg in this little arena on Lake Champlain and they just blow the guts out of each other. He tells that story. That’s still an interesting story. In fact, the British liked it so well that they wanted their own story and they wanted him to write the chapters about the Great Lakes. It’s still an interesting book to read.

Thomas Bailey: It was well-reviewed. It was accepted. The reviewers of The New York Times and like newspapers were astonished that this young man, he was 22 years old at the time, had written such a scholarly, mature, thoroughly researched book. Well, there’s Theodore Roosevelt for you, right?

Katherine Joslin: Right. The reason he wrote that book is because as a boy, he had traveled with his daddy, because they had real life experiences and that’s what kids need to have. He went to Plattsburg once and somebody gave him a cannonball from that battle on Lake Champlain and it just sparked his excitement about this military adventure.

His mother was from the south and lived on a plantation, and her brothers were confederate heroes, naval heroes, in the Civil War. He then visited them. After the war, they lived in Liverpool in England, and he would visit them and talk to them about the boats. He was just fascinated. Whatever he picked up fascinated him, but all of that stuff was poured into this book which started his career as an historian.

Brett McKay: I’m curious, throughout all of his work, and even beginning with the naval battles of the war of 1812, what was Roosevelt’s guiding ethos when it came to writing? Did he have an ethic or an aim he was shooting for with his writing?

Katherine Joslin: Yes, yes. He meant to tell the truth, mainly.

Thomas Bailey: He told the truth and he wanted the narrative of American history and American life to be presented as vividly as it could be presented. He wanted that in politics and he wanted that in art and he wanted that in all public life. One of the persons who was maybe most fascinated by him and in that notion of the national ethos was Walt Whitman, who said, “He’s got a little bit of the Dude, but he tells it like it is. It’s good. I like that stuff by Roosevelt.”

Brett McKay: That was another thing I thought was really fascinating about this time period was this sense of nationalism, not just politically, but culturally. Roosevelt and even Whitman, and you see it with Thoreau and Emerson, they were very self-conscious about, “We’re trying to create American literature, American art that rivals European literature or European art.” They had a chip on their shoulder.

Katherine Joslin: That’s right.

Thomas Bailey: There is a kind of national defensiveness. You’re right about that.

Katherine Joslin: What he thought, and he wrote about what the national literature should look like. He wrote an essay like that, and what he said about American writing is it ought to smack of the soil. Edith Wharton’s novel, her first novel was a historical novel about Italy, he wrote to her and said, “No, write about New York. We want to create our own writers here.” He was part of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, which is part of that whole movement, as you say, to give ourselves a national art and a national voice.

He was voted into that group, that very intimate group, in the second round in 1905 along with Henry James and Henry Adams. The people who voted for him were people like Mark Twain. He said, “You can study literature and ideas from other places,” he sounds like Emerson in this way, “But that doesn’t mean that we have ideas here.” He was full-throated in his notion that we should have a national literature.

Thomas Bailey: Right, and he wanted to find himself as an American American writer.

Katherine Joslin: That’s right.

Thomas Bailey: He really was intent on the national voice and the national experience.

Brett McKay: Another ethic that you highlight throughout the book, I love this line. I’m going to read it here. It’s from his autobiography about his writing. He said, “I have always have a horror of words that are not translated into deeds, of speech that does not result in action. In other words, I believe in realizable ideals and in realizing them, in preaching what can be practiced and then in practicing it.”

Katherine Joslin: That’s really at the heart of what he thinks about language. I think that’s true. That’s an American ideal. That first book of essays, or second book of essays that he writes when he’s fairly young, and even later in his life, he says, “Go back and read that. Those are the words that matter to me.”

Thomas Bailey: That’s interesting how that goes both ways. You can take language and turn it into action, but then you can take action after you’ve taken the action and go back into language with it and it becomes his books, and then his books become the source for law, which is a different kind of language, and a different kind of bringing action into language, which then shapes subsequent action.

He sees this as an ongoing continuum that moves back and forth, and then you read and you get new ideas and you consult with writers. You consult with John Burroughs. You consult with John Muir, and you come up with the idea for Yellowstone Park and Yosemite Park and the idea of the national preservation and conservation of land, but that starts in language and it starts an idea and then it comes back into law, and then you make it real. He’s always not content just to think about things, but to do things. I’m sure we’re going to get to the man.

Brett McKay: For sure. I was going to say, he did all these larger than life things, big hunts. He fought in Cuba. I was reading. I was like, “I wonder if he did those things so he could have something to write about.”

Katherine Joslin: Well, that is an interesting question. No, I don’t think he got up in the morning and thought, “Well, I’ll go out on a hunt because I can write about it later.” I think that’s the whole point is that action and writing come together. He went on the hunt. All those first hunts he went to in Dakota was because he came home one day and his wife and his mother on a Valentine’s Day died of separate things utterly by surprise, and he had to restore himself, and he went to his ranch in Dakota and started killing animals and trying to deal I think with the specter of death, and from that, he started to write. He said, “Well, I’ll have plenty of time writing out here,” and it was a way of mending himself.

I don’t think he meant to go out there to write, no, but once he got there, he took the pen with him and the pad and he did what he always did as a child. He continued to write about the adventure, and then of course he got better and better at that, so by the time he went to Cuba, he could come back in that very militaristic and full-throated way and become a hero and so overwhelmed people that they make him the governor of New York.

Thomas Bailey: By the time he goes to Africa and then later to Brazil, he’s invented for himself a much more daring kind of literary form, which is to write about it as it’s happening. He’d go out and hunt all day long or work or explore all day long, and when everybody else came home exhausted at night, he’d set up his desk and his lamp and he’d write about what happened that day and send it to the publisher without really any editing. The publisher would strike it into short stories and publish them in Scribner’s. Both books were published in Scribner’s Magazine, and then the chapters were collected into a book, and that’s a very risky kind of literary form. Almost all writers like to look over what they’ve written before they publish it.

Brett McKay: But not when you’re as confident as Roosevelt.

Katherine Joslin: Well, the idea of being confident and confident in the first draft probably comes from the fact that he started writing as a child and he was always comfortable in language, but you can look at manuscripts. They’re wonderful to look at. He would come in and he had pretty much the whole story in his head and he would run down the page very quickly, and then he’d go back and look at it and if he had anything else, if there’s anything he wanted to do, sometimes he would improve on a verb or something, but then he would do these balloons where he’d put more and more information in. He always added what he had to say, but there is a confidence in a writer that maybe you get from having written every day.

Thomas Bailey: I think there’s no doubt about that. He is sure of his own chops. He was sure of his own chops in all aspects of his life. I don’t think he ever thought he was wrong once, ever.

Brett McKay: No, yes, that’s true.

Thomas Bailey: He was self-assured and self-assertive in a way that really smacks of the 19th century. I don’t think males in the 21st century get to have that sense of assurance anymore.

Brett McKay: No, definitely. I’m curious, the way he approached writing, this first person account, mixing observation and history, did Roosevelt in a way fashion a new form of writing that influenced how other Americans wrote? Did he have an influence on the literary scene is I guess what I’m asking?

Katherine Joslin: Well, he knew writers of course and worked with writers all the time, but one of the contributions I think you could talk about, he meant to write an epic of the west. He wanted to do something where he put faunal nature together with hunting and he wanted to tell this story of what was going on in the west, and his friend, really close friend, was Owen Wister, who wrote The Virginian, and another was Frederick Remington.

If you put Frederick Remington’s sculptures together with Owen Wister’s novel, together with those stories about faunal nature and hunting, you could say that in that bundle, you really have the notion of how we talk about the west. The western comes out. I think he’s influential in that way.

Thomas Bailey: Yes, and what you end up with with Louis L’Amour is a kind of washed out western vision, a popularized and really over-romantic. Roosevelt would’ve been bemused, probably amused by the contemporary western novel, a Louis L’Amour kind of thing. No, he was at the heart of the invention of the west, our concept of the west, including the movies I think, probably.

Brett McKay: Without Roosevelt, we wouldn’t have John Wayne, maybe.

Thomas Bailey: You’re right.

Katherine Joslin: My mother would like that line.

Brett McKay: I’m curious what he would think of, my favorite western novel is Lonesome Dove.

Thomas Bailey: I think he and Larry McMurtry would’ve hit it off almost instantly, don’t you? Yes, and that was one of Roosevelt’s most endearing habits. He’d get into a book and he’d say, “I like this book and I like this author,” and he’d sit down and he’d write him and he’d invite him to dinner and then he’d corner him and they would just talk. He’d have had Larry McMurtry to the White House over and over.

Brett McKay: We’ve talked a lot about his writing life. Before we move onto his reading life, what was Roosevelt’s most popular book? A lot of people don’t realize this. That’s how he made his living. That’s how he supported his family. Even though he came from wealth, he lost a lot of it in the Dakotas on the ranch, so he had to write to feed his family and give them a comfortable life.

Katherine Joslin: That’s right, and remember, he’s a writer before he’s a politician. He’s a writer after he’s a politician, and it is his business to be a writer.

Brett McKay: Do we know how much he made as a writer?

Katherine Joslin: It’s really tricky to know. His finances were hidden, almost hidden.

Thomas Bailey: Yes. He wasn’t good with money. He was good negotiating a contract upfront, but he turned all the money over to Edith. She was a Victorian lady, and you can see at Sagamore Hill, you can see the budgets that she kept and they’re all budgets of expenses and not budgets of income. She kept that hidden, and he was quiet about it, too.

Apparently, and this is hard to get at, and you have to get at it indirectly and by implication rather than explicitly, the sales of Rough Riders were so expensive and so successful that it reestablished him and the Roosevelt family as a wealthy family. It was estimated in one article that I found in The Washington Post from 1901 that he had made $400000 of The Rough Riders, which in 1901, which was just a huge sum of money. He restored his fortune and he always was scrupulous about making money. He wanted to be paid for his work.

Katherine Joslin: He wrote three books while he was governor of New York. He said, “Once I get this office in the groove, I’ll give you my other books,” he said to his editors. They were living off the money that he was making as a writer at that time.

Brett McKay: Rough Riders, his story of his charging San Juan Hill in Cuba, that was his most popular book?

Katherine Joslin: Yes.

Thomas Bailey: Very popular, yes. That was a bestseller, for sure.

Katherine Joslin: Still is.

Thomas Bailey: It still is. It’s fun to read.

Brett McKay: No, yes, and then after that, I guess, what would be the second one? Would it be his African hunting book or the story about the River of Doubt?

Thomas Bailey: No, it was the African hunting book. The story of the travels through the Brazilian wilderness didn’t sell nearly as … It wasn’t disappointing exactly, but it didn’t sell as much as he had hoped, because he was out of the public sight and he had disappointed people by running on the Bull Moose ticket. While the sales were robust, they weren’t anything like the sales of the African book. The two bestsellers would have been The Rough Riders and Travels Through Africa.

Katherine Joslin: In terms of the retrieval work that we’re interested in doing, I think going back and reading those ranch stories, Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail is rather wonderful from 1888, or if you wanted to know about his politics and really understand him, he would say you should read American Ideals, which comes in 1897, a collection of essays and speeches, and then of course, The Rough Riders.

Many people read his autobiography, and we would say that the place to start in the autobiography, because he was so crabby by that time, is after he had lost at the Bull Moose and as he was angry about the resistance of Americans to be involved in World War I. In his autobiography, there’s a chapter called Indoors and Outdoors, which is just marvelous to read. Of course, we’re literature people. He has a book called History is Literature. It’s that essay about history is literature that I think is also quite good, and then, Tom, you would add, what, you think Through the Brazilian Wilderness, right?

Thomas Bailey: I think maybe Through the Brazilian Wilderness is a compelling read, and then when he was an old man in 1916, he published one last kind of nature book, book of essays, a kind of gathering of writing that he had done before and he had some later. It has a really wonderful title. It’s called A Book Lover’s Holiday in the Open, 1916. His introduction to that collection of essays is one of his really touching late pieces of writing. That’s very much worth going back to read.

Katherine Joslin: He even goes back and judges himself as a young man and trying to be a scientist and such, and he gives him a drubbing for not being any better than he was. You have this strange thing of the old man passing judgment on the young man. It’s wonderful.

Brett McKay: We’ve talked a lot about his writing life, but besides being just a prolific writer, Roosevelt was, as you said, even as a child, a voracious reader. Do we know how many books Roosevelt read in a given week? Did he have any preferences on what he read?

Thomas Bailey: First of all, no preferences. He would read anything. One of the charming things about him when he was in the White House was that he used the librarian of the Library of Congress as his personal librarian, and he would write him a letter and he’d say, “Send me 10 books on Hungarian history and I want to know something about the Irish Celtic myths and I want to know about the Nibelungen. I want to know this. I want to know that. Send me a stack of books.” The guy would send him a stack of books. He’d read them. He’d send them back and say, “Send me another.” He read by some estimates 300 books a year.

Katherine Joslin: What’s interesting I think about Roosevelt’s reading is it’s part of the myth of Roosevelt that he always read fast. He certainly didn’t want to be disturbed when he was reading, but he read, we discovered reading more closely in his letters and such, he read at different speeds. He read some things slowly and savored them.

He would sit with his wife in the evening and they’d read aloud from books that they liked, maybe from Vanity Fair or something like that, and they’d maybe just read the chapters that they liked or just the conversations, the way you might listen to music where you listen to parts of it and things that you enjoy. He liked poems, but he read certain poems over and over again. His reading was much more various and much more like the lives we all lead suppose in that there wasn’t any standard way to talk about him as a reader. He wasn’t picky at all.

Thomas Bailey: No. He loved certain classical writers. He loved Greek myths. He didn’t much like Shakespeare. He didn’t like Hamlet. He thought that Hamlet was kind of a disgusting character. Well, and that makes sense, doesn’t it?

Katherine Joslin: He used to joke that when he finished Jane Austen, he thought he had done something good for his soul.

Brett McKay: The other thing that impressed me about him is he read magazines, like trashy magazines of the time. I loved how you described how he read them, like he would hold them and then he’d just tear the pages out and throw them on the floor when he was done reading it.

Katherine Joslin: While he was waiting for the train, this is what people say about him, he would just go up to the magazine rack and he didn’t look through to see which ones he was going to do and always read the same thing. He bought all of them, and then he’d sit there while he was waiting and he was bored. He would tear the pages out of newspapers, too, because those were ephemeral. If you’re writing within a newspaper or a magazine, it wasn’t meant to last, and so you’d see the pages underneath his feet when he got done.

The reason he wanted his articles to go from magazines to books is that books are then treated in an entirely different way, and so that’s where the permanence in writing comes. He’d get really mad and he’s write to them. He was irritated with a Gibson Girl because what were women doing wanting to ride bicycles and not have babies. He thought they should have five babies. He’d get really concerned about all the aspects of life.

Brett McKay: Going back to this idea that he had no preferences about reading, I think a few times in his career, people would ask him, “Give us a reading list,” and he would basically say, “Just read what you want. I don’t have any preferences.”

Thomas Bailey: The president of Harvard, Charles Elliot Norton, had his five foot bookshelf with the classics and whatnot lined up, and if you read these, you’d be a well-educated man and somebody asked Roosevelt about that and man, did he tee off on that one. He said, “That’s a ridiculous idea. You can’t possibly prescribe to anybody how you read because reading is contingent. You start here and then you think, ‘Oh, that’s an interesting time in history. I want to read more,’ and you go there and then you branch off into the poetry and then you see what was happening in Spain at the same time, and then maybe you skip over to Hungary and try to find that out, too. You just read.

Katherine Joslin: The idea of formula, that you could have an education by formula, Edith Wharton found that just an appalling idea, as well. Education doesn’t come in a course and it doesn’t come in a course pack and it doesn’t come in a reading list. An education comes over the course of your life that you travel and talk with people and you read and you write and you’re engaged with living. That’s what education is.

Thomas Bailey: It’s certainly what education was to Theodore Roosevelt, who was an enormously well-educated man. He could speak in Spanish. He could speak in French. He didn’t think his French was very good. He didn’t have very good Greek, but he had pretty good Latin. He could speak German. He was broadly and deeply educated.

Brett McKay: I’m curious, how did Roosevelt’s reading influence his thinking about, let’s say public policy? Did that have an influence?

Katherine Joslin: Okay. When he’s reading, and this goes back to that whole idea of words into action and actions into deeds and such, but when he was police commissioner in New York, he met Jacob Riis, who had written How the Other Half Lives, and then they traveled through the slums to see what was going on. From that reading and from knowing Jacob Riis, he later thought of him, they thought of each other as almost family. They so adored each other.

When he became governor of New York, he knew about child labor, about the safety of women in the workplace, the safety of the workplace, the limited hours of work. He got interested in the purity in foods. He thought it shouldn’t say something on the label that wasn’t in a food. Later, when he was president and Upton Sinclair had written The Jungle, he worked with the publisher. Everybody was trying to get text into line because there were so many outrageous things that were in the book, but then he worked to pass the Pure Food and Drug Act. When he had these more imaginative pieces that he was reading, he could see the social betterment that could come from that, and then he did work in fact to turn those kinds of ideas into law.

Thomas Bailey: His ideas about government came from his fellow politicians more than they came from his reading, because he had the ideas, but he did consult with his political advisors and his political friends and he’d say, “I’m going to give this speech and I’m going to give it in Pottawatomie, Kansas and I want you to go through”-

Katherine Joslin: Osawatomie.

Thomas Bailey: Osawatomie, I’m sorry.

Katherine Joslin: Pottawatomie is in Kalamazoo.

Thomas Bailey: Yes, those were the Indians we got here. “I’m going to give this. Please take this part of the speech and rewrite it and put the stuff in there. Put the ideas in you think that I’m leaving out or approve them, and then give it back to me,” and then he would take this document and he would very carefully rewrite it, and then hand it over to his secretary and she would, he, whoever it was, would type it up and then he would read it. He pretty much stuck to his texts when he was giving a speech. The Osawatomie speech, it can be read.

Katherine Joslin: It’s a wonderful speech. By the time he collected these ideas together and he ran as the Bull Moose candidate in the progressive candidate third party in 1912, he had this packet, this very large speech that he had all folded up in his pocket and people probably know the story, but his glasses case was also in the pocket, so that when he was shot by a would be assassin in Milwaukee, the bullet lodged in his chest but it didn’t kill him. It could be that that long speech, it may in fact have saved his life.

Thomas Bailey: Of course, your listeners know this, but it’s worth repeating. That speech in Milwaukee is one of the primary examples of manliness on TR’s heart, right? There was the speech. He had folded it. He got up on the podium and he read it for 45 minutes. It was going to last another 45.

Katherine Joslin: Until he fainted.

Thomas Bailey: He was fainting. He was fainting from loss of blood, and they took him and they put him in the hospital very much against his will.

Katherine Joslin: His wife was so angry, yes. He checked his mouth to see if there was blood there and he thought, “If there’s blood there, I’ll die right here,” and he didn’t mind dying in a battle. That was heroic for him, but when he didn’t see the blood, he decided he’d go and give the speech. It was perfect for him. He loved the crowd and here he was with a bullet in his chest.

Brett McKay: Right. No, that’s awesome.

Thomas Bailey: It is awesome, and you know what? Like with so many things with Roosevelt, there’s another side to that, which virtually foolhardy that he didn’t take himself right straight to the doctor and get plugged up or something, but if he had done that, he wouldn’t be nearly as interesting a human being to us as he is.

Katherine Joslin: Even as he was dying in 1919, he was planning to run for president in 1920.

Brett McKay: Yes. He never stopped. He was always trying to turn words into actions.

Katherine Joslin: No, no, he never stopped.

Thomas Bailey: That’s one of the most compelling and astounding things about him is his absolutely insistence on plunging into the future. He just simply goes ahead and he goes ahead at high speed. It’s a remarkable thing about him as you read his life and think about it, how profoundly energetic he was and how profoundly committed to the future of the country and of himself and of his family.

Katherine Joslin: It doesn’t matter where you are on the political spectrum. I read this study recently, that he’s considered the number four president in quality and importance if you’re a republican, if you’re a democrat, or if you’re an independent, across the way.

Brett McKay: Right. He embodied the ideal of America that I think a lot of people have, energetic, forward-thinking, bold, adventurous, et cetera.

Katherine Joslin: I think he’s a figure that I say he’s ripe for a retrieval right now, because I think we live in a world where no matter who we are, we want to find this kind of model in history. What we have for him and we don’t have for other presidents is we have what we count as four dozen books, but 42 that he wrote on his own, and we can go back and have this much closer relationship with him through language.

Brett McKay: Well, this has been a great conversation. I’m curious, is there some place people go to learn more about your work and the book, or should they just go to Amazon or their local bookstore to go pick up a copy?

Katherine Joslin: Well, we are going to make the suggestion that they go to their local library and ask them to order the book if they’ve not done it. We believe very much in the local bookstore. We just had a book launch at a bookstore in Kalamazoo and I think that bookstores are back in fashion again. We’re at Barnes and Noble also and of course, at Amazon. We’re not hard to find. You can Google us.

Thomas Bailey: You can Google us and we pop right up, but if people are interested in buying the book, we really support the burgeoning market at local bookstores.

Brett McKay: No, yes, one just opened up here in Tulsa.

Thomas Bailey: Yes, terrific.

Katherine Joslin: The beauty of going to the local place, the library and the bookstore, of course, is that you can get our book, and then you can look around and you can find so many other things that interest you.

Brett McKay: Right. What’s great about our bookstore, it was started by the nonprofit reading foundation here in Tulsa, Book Smart Tulsa, which is very Roosevelt. Roosevelt would approve, right?

Katherine Joslin: Yes.

Thomas Bailey: Yes, yes, that’s cool.

Katherine Joslin: Absolutely, yes.

Brett McKay: All right. Well, Tom, Katherine, this has been a great conversation. Thank you so much for your time.

Katherine Joslin: A wonderful conversation. Thank you.

Thomas Bailey: Thank you, Brett. We’ve enjoyed it so much.

Katherine Joslin: This is wonderful. Thank you.

Brett McKay: Our guests were Thomas Bailey and Katherine Joslin. They’re the authors of the book, Theodore Roosevelt: A Literary Life. It’s available on Amazon.com or as they recommended, go check out your public library, recommend they pick it up, or check out your local bookstore. Also, you can find our show notes at AOM.is/TRwriter where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out The Art of Manliness website at ArtOfManliness.com, and if you’re interested in living TR’s strenuous life or at least something like it, check out our program, The Strenuous Life. It’s at StrenuousLife.co. You can sign up for updates when we open up enrollment. It’s pretty cool. We basically try to help you take action on things we’ve been writing about on The Art of Manliness for the past 10 years, so go check it out, StrenuousLife.co. As always, thank you for your continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.