Back in 2015, I had Starting Strength coach Matt Reynolds on the podcast to talk about barbell training. At about the same time, I started getting online coaching from Matt for my own barbell training. A year and half later, I’ve made some incredible gains with my strength and hit personal records that I never thought I’d be able to attain. Thanks to Matt, I was inspired to have recently entered my first barbell competition, and deadlifted 533 lbs, squatted 420 lbs, and shoulder pressed 201 lbs at the event. And perhaps best of all, my body has stayed healthy and I haven’t been injured in the process.

Because guys frequently ask me about my training, I’ve brought Matt back on the podcast to walk listeners through the programming and nutrition plan I’ve been following for the past 18 months. We discuss how Matt customized my programming, and why he started me with the novice Starting Strength program even though I had been barbell training for a few years. We also dig into my setbacks and how Matt adjusted things to help me break through plateaus.

If you’ve been thinking about barbell training or are currently training and are confused about how to program, you’re going to get a lot out of this episode. Consider me your human guinea pig.

Show Highlights

- Why Matt decided to sell his gym and do online coaching full-time

- How online strength coaching differs from in-person coaching

- The surprising benefits of online coaching vs. in-person

- What to look for in a good online coach, no matter your fitness domain and interests

- My own experience with online strength coaching — from novice to now entering competitions

- Why you want to stay as a weightlifting novice for as long as possible

- Why gains are harder to come by as you are able to lift more

- The stress-recovery-adaptation cycle

- The downsides of lifting more weight

- How my diet changed as my lifting programming changed

- What is DUP programming? And how it helped my up my game

- How signing up for a powerlifting competition changed my programming

- My post-competition programming and recovery period

- What “work capacity” is and how it’s worked into coaching strategies

- My unlikely hamstring injury

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- Barbell Logic Online Coaching

- My first podcast with Matt Reynolds

- My podcast with Mark Rippetoe: Part I & Part II

- My barbell videos with Mark Rippetoe

- Know Your Lifts series

- AoM Instagram — check out videos of my lifts here, here, and here

- My podcast with the Doctor of Gains

- Daily Undulating Periodization

- DOMS — Delayed Onset Muscular Soreness

If you’re looking to get stronger than you ever thought possible, check out Barbell Logic Online Coaching. If you’re not ready to jump into online coaching just yet, at least pick up a copy of Starting Strength by Mark Rippetoe.

Connect With Matt Reynolds

Starting Strength on Instagram

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Shari’s Berries. Get Mom an amazing Mother’s Day treat starting at just $19.99. Visit Berries.com, click on the microphone in the top right corner, and use my code “Manliness.”

Dollar Shave Club. New members get their 1st month for $5 with free shipping. You can only get this offer exclusively at DollarShaveClub.com/manliness.

Recorded on ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. Well, back in 2015 I had Starting Strength coach Matt Reynolds on the podcast to talk about barbell training. About the same time I started getting online coached by Matt for my own barbell training. A year and a half later I’ve made some incredible gains with my strength, and hit PR’s I never thought I’d be able to attain. Thanks to Matt I was inspired to enter into my first barbell competition back in April, and I deadlifted 533 lbs, squatted 420, and shoulder-pressed 201 at the event.

And, perhaps best of all, my body’s stayed healthy and I haven’t been injured in the process. Well, except for one injury that was not barbell training related. We’ll talk about that in the show.

Because guys frequently ask me about my training, because I’ve been posting my progress on Instagram every now and then, I’ve brought Matt back on the podcast to walk listeners through the programming and nutrition plan I’ve been following for the past 18 months. We discuss how Matt’s customized my programming throughout this time, and why he started me out with the novice Starting Strength program, even though I’ve been barbell training for a few years. We also dig into my setbacks and how Matt adjusted things to help me break through plateaus.

If you’ve been thinking about barbell training or currently barbell training and are confused about how to program, you’re going to get a lot out of this episode. Consider me your human guinea pig. After the show’s over, make sure you check out the show notes at a1-is/reynolds where you can find links to resources. We’re going to delve deeper into this topic.

Matt Reynolds, welcome back to the show.

Matt Reynolds: Thanks for having me again, man. We’ve upgraded out of your closet.

Brett McKay: Yeah, we’re not in my closet today. You are starting a podcast so you’re in Tulsa, and you’re doing a podcast yourself, and you have this pretty fancy studio here with fancy equipment, so we are not in my closet like last time. Like, you’re a big dude, I’m kind of a big dude.

Matt Reynolds: You’re a big dude now.

Brett McKay: I’m bigger now.

Matt Reynolds: Yup.

Brett McKay: So, it was a tight squeeze, but great to have you back.

Matt Reynolds: Thanks for having me.

Brett McKay: I’d like to talk a little bit about where we picked up from last time. Last time we talked, you owned a gym, like an actual, physical gym, in Springfield, Missouri, one of the largest barbell strength gyms in the country. You no longer are an owner, and you’ve transitioned completely to online coaching. Can you talk a little bit about… you know you don’t have to go into any details about the specific transition. What was the transition like from coaching in person to coaching online?

Matt Reynolds: Sure. Yeah so I sold my gym at the end of 2015, in December of 2015, and started online coaching full time. I honestly didn’t know how well it was going to go in the beginning, so it was one of those deals where I had made enough money from the sell of the gym that I had at least a handful of months that I could do this online thing and see if it worked. And, so I had a pretty good number of clients already, you know I had been working with you since, I think, October of 15. So, I had maybe 30 or 40 clients at the turn of the year, so in January 2016, and had enough capital in the bank to basically just put my time and devotion into this full time.

So, wanted to see how it would go, and I poured into the online coaching and started doing that full time. I had certain issues with online coaching. Online coaching’s different, right? And so in-person coaching allows you to make changes, or fixes, or cues, in realtime with your clients. And, online coaching doesn’t allow you to do that. The degradation with in-person coaching versus online coaching is that it occurs… I can make changes to your form in session-to-session, from one session to the next, rather than from rep-to-rep. And, so there is a little degradation there so I wanted to try and do it better than I thought it was being done, and really provide the best service I could.

So, I poured into the full time and it started to grow, and it grew well. One of the downsides of online coaching was the platform. So, most people that use online coaching, online coaching to this day is, right now, a big, really, probably multi-billion dollar industry, and one of the problems is that most people use a platform that is some combination of email with probably spreadsheets, Google Docs, or Excel-type sheets. And, I did that, and did it for awhile. But, as it grew, I realized that I would wake up in the morning and have 125 emails that all needed responding to, and videos to break down and what not.

So, I recognized that the platform wasn’t very scalable, and so in April of last year, April of 2016, I started to work on a platform that would be scalable so we can go from 60, or 70, or 80 clients, to 200 or 300 or 500 clients without any loss of service. I wanted service to increase and as the business grew I wanted the personal back and forth between myself and my clients to continue to get better while the administrative duties for both coach and client got less. So, that’s really what I focused on and that’s really been the source of our growth over the last year.

Brett McKay: All right let’s talk a little briefly now about online coaching a bit and how it’s different from in-person. You mentioned a little bit with in-person coaching, you’re a Starting Strength coach, barbells, and form is really key part of the Starting Strength philosophy. You want to make sure you’re doing the list correctly so it’s efficient, you can lift as much weight as possible without injuring yourself. And Rippetoe, himself, has always kind of bashed online coaching, because as you said you can’t get that in-person coaching where people can, you can get cues in real-time saying you need to lift with your butt more, shove your knees out.

So, how do you get around that with online coaching when you’re not there with your client? How do you do that form breakdown and give those cues they need?

Matt Reynolds: Yeah, it’s a great question. So, first, we’ll even back up one step further. Most people who do online coaching, what they call online coaching, is in fact not online coaching. It’s online programming. You pay a fee and you get a printout of an Excel document. And, that’s not really coaching, that’s just programming. And, maybe there’s even diet attached or whatnot, but for us the thing that we really wanted to bring to the table was the actual coaching portion. Which, when we define coaching through Starting Strength we say, “Coaching is getting a lifter or an athlete to move the way I want them to move based on a specific model.”

So, I’ve got a model that Starting Strength has set up. We know the correct way to squat, the correct way to deadlift and to bench press and to press. How do I get my online clients to perform those lifts, as close to that model as possible, with the obvious drawback that I’m not standing there in the room to get them to do that. And, so what we do is we teach people, one, how to video themselves on their cellphones. So, for all of our clients, all they need to do online coaching is an iPhone or an Android, we teach them to angle the video themselves at. So, for example, for videoing the squat, we video at about hip height, and kind of equal between the back and the side. So, really where a coach would stand.

And then they video their lifts, so they get their programming on a very clean, beautiful app called Fitbot that we love, and then they get their programming there and they can upload their video and send it to their coach. So, they video themself squatting, and then the coach has ways to look at… we look at those on our computer, we break those down with different photo-editing apps, we can screenshot it, we can point, you know, “Your knees are here, they should go forward.”

So, there’s certainly a difference. The difference is that I can’t do it in realtime. That is a consequence of online coaching, but a benefit of online coaching is that I can pause your lifts. I can watch your lifts at 25% speed. Things that the human eye can’t see in realtime because it’s too fast, something like a power clean, or something that’s fast where there’s just a little bit of knee sliding forward in the bottom of the squat. That somebody might miss in realtime, I can watch your squat over, and over, and over again 10 times, 15 times, if I need to pause it, slow it down, screenshot it, show you what I’m seeing. And, so the visual cues become actually far more important in online coaching than they are in in-person coaching.

In-person coaching is primarily an auditory experience. I’m telling you to do this and I utilize things like cues, which are short reminders of something I’ve already taught you. So, hip drive, middle of the foot, knees out, eyes down, things like that I will say in online coaching. Or, I will say in in-person coaching. But in online coaching I can actually use visual cues. I can show you when your knees come forward, I can’t do that in realtime in-person coaching. So, there are both advantages and disadvantages to both. And, it’s worked really, really well.

It slows down the form fixes. Online coaching will slow that down a little bit from what you get in realtime, so if you come and see me, you drive to Springfield, Missouri, and get a session with me in person, I can really clean up your squat, or your deadlift, or any of your lifts quickly in an hour session. In online coaching that’s going to be slowed down over the course of several sessions, you know from the before five, six, ten sessions, but what we’ve seen from our experiences is that people, after they’ve worked with us for several weeks, have tremendous form in their lifts just based on, you know, you just take nice, clean easy cues. You give them something that’s still assertive and easy to remember. Something that’s not a lot of text, so they can walk into the gym, on the next session, and remember, “This is what I’m trying to do. This is what my coach told me.”

So, that’s the difference, really, between in-person and online.

Brett McKay: Right, so it just takes longer to clean up stuff.

Matt Reynolds: Yeah, it takes a little longer to clean up. But it’s a fraction of the cost.

Brett McKay: Well, yeah. Yeah it is because you’re not giving that in-person session. That’s another benefit of online coaching.

Matt Reynolds: Yeah, correct. I mean, good coaches are expensive, and depending where you are in the country, a Starting Strength coach is going to run anywhere from $100 an hour to $200 an hour, depending on where you are in the country. And, online coaching for us, costs around $200 a month. So, for what you would get only two hours of in-person coaching for, you get an entire month worth of coaching through Barbell Logic Online Coaching. So, it works very well.

Brett McKay: All right. How many clients do you guys have now?

Matt Reynolds: So, we’re running between three and four hundred, so over three hundred and under four, and we’re growing quickly so we grew about 20% last month. We’re up about 13% this month. So, it continues to grow quickly. We have 35 Starting Strength coaches that work for us now, all over the country. And, one of the other great advantages of online coaching, at it’s most basic foundational point here, is that if you don’t have access to a great coach in your town, and most people don’t, you have access to a great coach online. We have about 30% of our clientele is international.

And, so, we only have three or four international Starting Strength coaches, so for these clients who are all over the world, that have never had access to an in-person Starting Strength coach, they now have access to a Starting Strength coach from the privacy of their own home, from their own gym, from their garage gym. They can have access to a Starting Strength coach at a fraction of the cost that it would be for in-person coaching.

So, you have a coach in Tulsa for the first time in ever, and so just this year you’ve got a coach in Tulsa. But, before that you didn’t have access to a coach. Oklahoma City doesn’t have access to a coach. Cheyenne, Wyoming, didn’t have access to a coach. Nashville doesn’t have a coach. You’ve got some major cities in the United States that don’t have a Starting Strength coach. And, so these people now have access to a coach wherever they are, and certainly people who living rural areas, who would never have access to a Starting Strength coach now can.

Brett McKay: Right. So, besides the form checks, you do programming, but it isn’t just an Excel sheet. I mean, just based on my work with you it’s very customized. You take a look at the videos, I give feedback like how that session felt, and then you adjust things, oftentimes, on the fly for my next session. Right?

Matt Reynolds: Yeah, correct. So one of the things, you know, we wanted to move away from cookie cutter anything and so for us when you sign up for our service you fill out a pretty in depth questionnaire, it’s going to take 20 minutes or so to fill out that questionnaire. You send that in and then I really pour over that questionnaire and try to pair you with the best coach possible for you. So, I look at demographic, and geography, and what your goals are, and how advanced of a lifter you are. And, I pair you with a Starting Strength coach that’s going to work really well with you. And then they start to work with you.

You’ll do a test workout for us, so we usually just have you do a basic test workout of working up to a moderately heavy set of five on the major lifts. We break down those videos. And, then, your coach will start to program for you. That program is done, again, on an app called Fitbot that runs on your phone. You can take your phone into the gym with you. You can see your own program, again, it’s specifically tailored to you, your needs, your advancement. So, we have clients from absolute beginners, who have literally never touched a barbell before, all the way through advanced power lifters. We’ve got a guy that squatted 850 lbs raw, you know has over 500 lb bench pressers. So we have the entire gambit of advancement of lifters.

You go in the gym, you pull up your app, you see what the program is. So, it might say, “Brett, you’re going to squat today. You’re going to squat 365 lbs for two sets of five”, and you go and you squat your 365 lbs for two sets of five. You respond back on the app how it went. So, “I squatted my first set was easy, second set was harder than I thought it would be. First three reps was easy, next two reps were hard”, and you complete that squat.

When you do, when you complete the lift and then when you complete the complete workout, then it pings my phone and it tells me, “Brett McKay has finished his workout.” And now, I can go on a see what your workout looks like. I can watch the videos from the workout, and within 24 hours of your workout, your coach, which for you is me, will break down your videos completely within 24 hours so that by the next time you train you have things to go into to work on in the gym. So, it’s a really nice, it’s a really nice service.

So, yeah we do complete programming, complete video break down, form coaching. And, then we also do a fair amount of nutrition work with our clients as well. So, it’s really a complete package.

Brett McKay: Yep. Let’s talk about just online coaching in general, because some people who are listening might not be interested in barbell training.

Matt Reynolds: Sure.

Brett McKay: Besides being an online coach yourself, you also consult other individuals who want to be online coaches in other fitness domains.

Matt Reynolds: True.

Brett McKay: What do you… what should… if someone’s looking for online coaching for, say, long distance running, crossfit, obstacle course racing, whatever it is, what should they look for in a good online coach?

Matt Reynolds: Sure. Well, the first thing I would do is I would figure out who the best coach is in general. Like, I would just… the best in-person coaches are still going to be the best online coaches if the platform is there for them to do that. And, so, one of the nice things about the online world is that it’s opened up the opportunity for people to have access to great coaches who wouldn’t already have it. So, if you’ve got a great triathlon coach who lives completely across the country on the opposite coast, you potentially could hire this person to be your online coach. That would be first. I would look for people who just are generally known as the best coaches in the sport.

And then, two, does that person offer true personalized coaching? Or, what they do… 80% of online coaching out there is just cookie cutter programs. So, here’s a program for power lifting. Here’s a program for half marathons. Here’s a program for whatever it is.

I guess for some people who are looking for a really cheap price point, an entry point of maybe $30, or $50, you just have to recognize that’s not online coaching. What you’re doing is you’re buying a program.

And, then, I think ultimately coaching is, at whatever sport you’re doing, whatever thing you’re training for, has to come down to form. So, if I were going to hire somebody to do triathlon coaching, I actually want to be able to have someone who can watch me run, swim, bike. I want someone who could actually walk me through what the form looks like. If I want to do distance running and somebody’s trying to teach me how to do pose running, I want to make sure that… I ought to be sending videos of what my feet, what my ground striking looks like.

And, so really that’s what I’m looking for, is not something that’s an Excel document, or a Google docs, or a sheet for $50 or even an auto-pay of 25 or 30 bucks a month. I want coaching. So, as long as we understand that coaching is different than programming and just getting that cookie cutter program, the reality is if you want to train for a half marathon, that’s very different than a 19 year old kid training for a half marathon, that’s run cross country at a school for the last four years, and it’s even further different from a 45 year old overweight mom, who’s trying to train for a marathon or half marathon just to try to get in shape.

So, a beginner marathon, or training for a marathon program is not going to work. It just doesn’t work across all fields. And, so one of the things we try to do at Starting Strength is we very much differentiate between beginners, novices, intermediates, and advanced. The program looks totally different. We want the programming to be simple, what I say is simple, hard, and effective. It’s as simple as it can possibly be for that advancement, and then we’re going to get a little more complicated as we grow.

And, so that would go across all sports. If I’m hiring somebody to be a swim coach, or run coach, or bike coach, or whatever those things are, or movement coach, I want somebody who’s going to actually coach the movement patterns, not just the program.

Brett McKay: Right. Well, that’s awesome. I thought it would be useful to talk about my experience with you, with online coaching because I think it’s a very indicative so I get a lot of questions about it as well, people asking me. I’ve been posting stuff on Instagram, and people ask me about my training, and they’re, like… I did a deadlift, the Starting Strength challenge, whatever it was, like 533 lbs, and I always get questions, like, “What was the program you used to do that?”

Because, I think people think, “If Brett did that, if I did exactly what he did I will deadlift 533 lbs too”, but that’s, as you said, a difference between novice, intermediate, and advanced. So, let’s talk about how I got to that point.

Matt Reynolds: Sure.

Brett McKay: So, I started working with you in October of 2015.

Matt Reynolds: Yeah, correct.

Brett McKay: And, what was the strategy? What kind of program was I doing at the very, very beginning?

Matt Reynolds: Well, you did the novice Starting Strength linear progression program.

Brett McKay: And why did I start out with it? Because, I had been lifting, like, I mean, I think that’s another thing people need to understand is there’s a novice, intermediate, advanced. I think a lot of people think when they see novice they think well, it’s just a ranked beginner, “I’ve been lifting for five years. I don’t need to do that”. So, I’ve been doing barbell training for awhile but you still started me with that. Why is that?

Matt Reynolds: Barbell training is the one place where you want to be at Novice as long as you can. All right, it’s ingrained in our instinct to not want to be at novice. “I don’t want to be a novice guitar player, I want to be an advanced guitar player.”

The problem is that in barbell training, novices make the greatest gains. The very, the simple thing that novices can do that nobody else can do, is they can add weight to the barbell every single time. And, so when I first go you I knew your form was decent but not great, we had some things we had to clean up in your form. So, what I did was I just backed off your weight a little bit from where you were, so I took some of the weights that you were lifting for maybe one set of five, I backed it off maybe 10, 15%, I made you start doing weights for three sets of five, and we just added weight every single time. So, you squatted three days a week, you alternated your benches and presses, and you deadlifted three times a week.

And, we did that as long as we could, which wasn’t that long, but as long as you can add weight every single workout, why would you do anything else? So, the person that makes the most gains is the person who is able to stay at a novice linear progression program, like Starting Strength, for as long as possible. So, you know, we have people we see stay on this for four, five, six months. For you it took two months. So, after two months, you couldn’t add weight every single workout. Right? You started out, and most people will do this, you started to crap out on the press first, so you weren’t able to continue to add two and a half pounds, or five pounds to the press. We couldn’t go up anymore on the press. And, then the bench press died out and then eventually the squat and the deadlift did.

Which was great. So, we got you to a point where you continued to make progress, adding weight every single workout. Every single workout. I mean, you literally you would do it on Monday, you would go up on Wednesday, you would go up again on Friday, you would go up again the following Monday, and so on and so forth for two months. And when that slowed down we had to spread out your progression to weekly progression. And that’s when we introduced the concept of Texas method, so you did kind of what I would say a little bit of a Texas method bastardization.

You’re old enough that doing things like Texas method utilizes five sets of five squats, and I thought that was too much for the volume for you, especially compared to, you know I look at the amount of work that you do on a daily basis, and I’ve come out and visited with you at your house. You know, like you’re a high stress guy, you’ve got lots of work to do, and you’re an ambitious guy, you’re running the website, and entrepreneur, and business owner, and so I knew that five sets of five for a guy your age and with your recovery ability was probably going to crush you. And, so we backed it off a little bit and we did three sets of five. One time we started alternating, after a few weeks, between upper body and lower body, and we still made slow, progressive progress.

And, we did that for several months. We did that for most of the first half of 2016, making progress there. So, that was the first two programs.

Brett McKay: Right, so what was that… what would happen if someone, if they were a novice, they went to an intermediate or an advanced program? So, I think some people would see, like, 5-3-1, and it’s really popular, it’s a great program, and they’re, like, “I want to do that. It sounds awesome.”

Like, why… what would happen if they did that? What would they be missing out on if they went immediately to an advanced or an intermediate program?

Matt Reynolds: That’s an easy… so, 5-3-1 is an excellent program, it’s a program that you make progress on. You basically hit fives the first week, threes the second week, singles the third week, and a de-load the fourth week. So a backed off weight the fourth week. And, it’s essentially a one month long program. So, you’re making progress, essentially you’re hitting new maxes once a month. And, so the problem with that is that if you go in and say your squat is 175 lbs, which we would consider for a normal weight male, somebody who weighs around 200 lbs, that’d be an under body weight squat. 175 for a single. You are still a novice, almost for sure.

If you’re in the 5-3-1 program, by the end of the 5-3-1 program, you might actually squat 185. So, you might’ve put 10 lbs on your squat in a month, which is progress. The difference be tween that and linear progression is I could’ve had you squat 175 on Monday the first week, and 180 on Wednesday, and 185 on Friday. So, by Friday, you could’ve had the same progress. And then, 190, 195, 200. By the time you get to the end of a linear progression, in the same month, you’re probably squatting 225, 235, as opposed to 185. So, an intermediate program slows down the progress.

Now, to put things in perspective, I deadlifted 700 lbs for the first time in 2005. My current max on deadlift is 725. It’s 2017. So, in 12 years, I’ve put on 25 lbs on my deadlift. And, if I had to eat dog poop every day for the next year to deadlift 730, I would. That’s the difference between an advanced lifter and a novice. Like, a novice adds five pounds to his deadlift in two days. And advanced lifter adds five pounds to his deadlift in two years, or longer sometimes.

Brett McKay: Well, why is that? What’s going on there with the physiology? Why can’t you, as you get more advanced, why can’t you… why does it take longer to increase your max?

Matt Reynolds: Well there’s several reasons. One is you develop an efficiency of your motor pattern. So, in the beginning as a novice, you’re not super efficient. And, so while you are certainly gaining contractual hypertrophy, like you’re actually, your muscles, the contractual portions of your muscles, are actually getting bigger and stronger, and you’re able to adapt to that and get bigger and stronger. You think about how long it takes to recover from deadlifting 225 lbs. Not that long. How long does it take to recovery from 700 lb deadlifts? Seemingly longer. How much muscle mass does it take to pull 700 lbs? What does it do to your central nervous system? You know, you just did a meet. You competed for the first time, you felt like you were run over by a truck for the first week. Why? Because you did nine really heavy lifts at the meet that most people don’t do that every day.

So, as you become more advanced it becomes far harder to recover. We look at this cycle, we call it the stress, recovery, adaptation cycle. I stressed the body with the workout, with the training, I recover from that, and my body then adapts so that it can handle something bigger, and greater, and tougher next time.

Well, when I’m in novice, that entire cycle essentially takes two days. On Monday I can squat, I can press, and I can deadlift, and it’s hard for me but it’s ultimately not that heavy. On Tuesday I basically recover from that workout and by Wednesday I have adapted to that workout, and now I can handle more weight than I did on Monday.

As an advanced lifter, that stress, recovery, adaptation cycle might literally take 12 weeks to truly build up the fatigue and stress needed to be able to then recover from an intense amount of stress and fatigue, and then adapt to something that’s going to take me from a 725 deadlift to a 735 deadlift. So, a ten pound jump at that level is going to take a tremendous more stress, which then it’s going to take more time to recover from to elicit a very small adaptation of only a 10 lb increase. It’s very, very difficult to do. But, for novices it occurs in a two day period.

Brett McKay: Right. So, this is why if you see some really super, strong dude on Instagram, pulling 700 lbs like you, following their program, saying, “Hey, what program did you use to do that?” Like, it’s not going to be really useful for that person.

Matt Reynolds: As a matter of fact, most strong athletes get strong in spite of their programming, and in spite of their form, not because of it. The reality is that genetics are incredible for some of these guys. Sometimes performance enhancing drugs are incredible for these guys. And, the combination of genetics and potentially drugs, are something that most 35 year old listeners of Art of Manliness, don’t want to do and can’t do. And, rightly so.

I’m trying to get normal people generally strong. So, there’s also a difference between… like, where you’re at right now, when you came to me you were not very strong and you weren’t in very good shape, and I wouldn’t say you were necessarily unhealthy but as we’ve worked over the last year and half you are now very strong and healthier than you’ve ever been. You can tackle anything that life throws at you but you’re also at a point where now you have to start to make a decision.

You are strong enough today to tackle anything that life throws at you. And, so you’re healthy, you haven’t dealt with hardly any injuries over the last year and a half, but now you have to make a decision. You deadlift 535. To deadlift 600 lbs, to get even stronger, now it’s going to push more towards the competitive side and less towards the health side. So, you might have to risk the potential of injury, of whatever, in order to reach 600 lbs. So, there’s a difference there as well.

For most of your listeners, they just need to get generally strong, and generally strong is strong enough. At that point they can decide, “Do I want to keep getting stronger and potentially risk injury, or even health decline?”

So, deadlifting 800 lbs, your body’s not really made to do that. But you should be able to deadlift more than 200 lbs if you’re an adult male. Like, that’s not a… my wife deadlifts 400 lbs and you’ve seen her, she’s a totally, totally normal-looking soccer mom. She’s not big, she’s not strong. I mean she’s strong, she’s not muscular, she’s not even that into it. But, she deadlifts 400 lbs. So, a normal guy would be able to deadlift 400 lbs, that’s not a hard thing to accomplish for anybody.

Brett McKay: So, what say you reach that point. You make that decision, “Okay, I’m strong, generally”, what say you decide you don’t want to lift anymore. You don’t want to… what would be the program for that? You gain a basic level of strength, what do you do after that?

Matt Reynolds: So, when you say you don’t want to lift anymore, what you really mean is you don’t want to continue to get stronger with the barbell.

Brett McKay: Exactly, so you don’t want to lift, you don’t want to deadlift 700 lbs. You’re happy deadlifting 500.

Matt Reynolds: Yeah that’s totally fine. We can just do a maintenance program that holds your strength where it is. Maybe that’s two times a week training, two times a week for most people will maintain. It’s difficult to make progress at two times a week. We have some of our older athletes, so guys that are maybe 50 years old and over. That’s a really blanketed statement, but depending on what your recover ability is, most of our adult males who are 50 and over will only train twice a week because they just don’t… they don’t have the hormonal capacity, and just the wear and tear on their bodies, the shoulders, the hips, and the knees, can’t recover to be able to train three times a week so they might train twice a week.

But, for most guys, twice a week will maintain. So, we’re still going to lift relatively heavy twice a week in order to maintain your strength, and what we’re going to do is add other stuff in that you want to do. So, if at that point you want to do mud runs, or you want to play tennis, or play golf, you have more time to do those things if you want to now that you’ve established this base of strength.

One of the interesting things about strength is, to me one of the most interesting things about strength, is of all the physical abilities… so if you think about all the physical abilities that you can have, power, and speed, and agility, and mobility, and cardiovascular conditioning, and all those sorts of things. Strength is the slowest to build. It takes the longest to build, but it also takes the longest to lose. So, you can get really strong.

You know, it took you the last 18 months to work with me to get pretty dang strong. It takes a long time. You can’t get this in a month. But, if you didn’t lift a thing, if you went on vacation for the next month, you went down to Mexico with your family, didn’t touch a barbell and came back a month later, you’re still pretty strong. Like, you might only end up with, say, a degradation of eight or ten percent in your total strength, which would still leave you far stronger than the average American male.

But, cardiovascular conditioning is very quickly built and very quickly lost. So, if I want to get in really good condition for, let’s say, you’re going to go do a mud run, or adventure race with your wife, you can get in pretty good condition for that in two or three weeks, but then if you also go down to Mexico for a month, and you go hang out on the beach and you don’t really do any exercise at all, you’re going to come back to be really, completely what we call shape, for cardiovascular conditioning. So, very quickly gained, very quickly lost.

So, because of that issue with strength, because strength is so slowly lost, that it’s pretty easy to maintain strength and hold it, especially as we get into our older years, and we get into our 50s and our 60s, it’s not that difficult to hold onto the strength that you have. You might not be able to continue to gain strength at 62 years old, especially if you’ve been lifting for the last 20 or 30 years, but it’s not that hard to maintain.

Brett McKay: All right, so let’s… I’ll start off, I think it’s important to say before I started training with you, my body weight was, like, 180, 185. A year and a half later I’m at… like, I peaked at the competition, I was 226, I weighed in at. So, that’s, like, 40 pounds of weight and I haven’t really gotten fat. I mean, there was times where I did get fatter, let me talk about the diet component of this part.

The diet changed. Sometimes you’d reduce my calories, sometimes you’d increase them, like, I think at one time I was eating 3500 calories a day. So, how do you, as a coach, determine whether a client should increase or reduce calories?

Matt Reynolds: That’s a great question. It comes back to the stress, recovery, adaptation cycle. If I can stress you enough that you can recover, and adapt, and make strength gains, then you’re eating enough calories. At the point that that stops, not stops for one day, I mean, every body has a bad workout or two, but stop for a week or two, you’re struggling to hit your numbers, then we’ve got to increase your calories. Your recovery is not enough.

One of the hardest things about a coach is I can control your workouts and if you’re honest with me, my clients are honest with me, I can have a fair control of their diet. But, things like outside stress, family stress, work stress, lack of sleep, sickness, we’ve been through all of those things with you over the last 18 months, that adds to that stress and the stress, recovery, adaptation cycles. When I say stress, what I’m specifically talking about is the stress we put on the body during the workouts. But, the body doesn’t really understand the difference between the stress of a 400 lb squat and the additional stress that’s added to your life in those two days, between, “Hey, I didn’t sleep very well. Hey, I’ve got a sinus infection. Hey, my kids were sick and they kept me up last night because they were sick.”

Whatever those things are, I can’t plan for those. So, I have to start looking at the stress. Is the stress, recovery, adaptation cycle working? Am I stressing Brett enough so that he can recover and adapt? Or, am I stressing him too much and I have to back off on the stress? Or, is he recovering too little and we’ve got to increase the recovery?

Some of those things are in my control and some of them are not. And, so, we started to look at your training, and while you making progress we kept you at a pretty solid maintenance calories. When you stopped making progress and you started to get achy, and you’d get lethargic, and you would lose some interest, and, “I really don’t feel like training today, my joints are hurting, my elbows are…”

Okay, we’ve got to bump up our calories a little bit, and we need to actually focus on making sure you get enough sleep so that we can continue to drive the progress and the adaptation.

However, when things are going very well, and you say, “Hey, I keep checking my waist measurement, and my waist measurement is up an inch and a half,” a lot of people think that Starting Strength is a way to get you fat. It’s not.

Brett McKay: That’s what everyone says, that you’re going to get fat.

Matt Reynolds: Yeah, of course.

Brett McKay: You’re going to look like Rippetoe, he has a belly.

Matt Reynolds: Rip is 60. And, Rip likes whiskey. So, the thing is, and here’s the other thing, Rip’s not really that fat. Like, his belly is as hard as rock. That’s a guy who’s lifted his entire life, he’s just got a… he’s built an enormous amount of muscle. But, it also, when Rippetoe talks about a gallon of milk a day sort of diets, this was made for a 19 year old kid that weighed 155. Not a 37 year old 210 lb listener of Art of Manliness. That’s not who needs to drink a gallon of milk a day.

I’ve never had you drink a gallon of milk a day, and you’ve still gained 40 lbs… you’ve probably gained, of the 40 lbs or so that you’ve gained, you’ve probably gained 28, 30 lbs of muscle and 10 lbs of fat. Now, if you think about it, if you gain 30 lbs of muscle and 10 lbs of fat, your body fat percentage still went down. So, it’s still because we added so much more lean mass.

So we just look at the stress, recovery, adaptation cycle. As long as we’re making progress we stay the course. When you get the point where you feel uncomfortable with the waist size, you say, “Well, my waist was here, it’s up an inch and a half”, okay let’s back this off a little bit. Let’s back off your carbs, especially back off your carbs on non-training days. That’s why macros count, you know you hear the podcast with Jordan good buddy of mine, Dr. Gains, it really walks through all those details in the previous podcast you did with him, and that’s really what…

It’s the same thing, it’s the same concept that I use for nutrition is the same thing that Jordan does.

Brett McKay: So, we talked about what we did for the first few months of my training. We did Starting Strength linear progression, we moved onto a modified Texas method, then you switched me to this thing called “DUP”, and I hated that.

Matt Reynolds: It worked real well, though.

Brett McKay: It worked well but I hated it, especially deadlift day. That was the worst. So, what is DUP and what’s the thinking behind it? Is it an intermediate or an advanced?

Matt Reynolds: That’s a good question. So, DUP stands for Daily Undulating Periodization. You can find lots… I did not invent Daily Undulating Periodization. This is a type of program that’s been around for awhile. It essentially, anytime we’re laying out programming, we can modify one of several variables. We can modify the intensity.

Now, most people think of intensity as how hard was it, that’s not what intensity means. Intensity means how close to, in percentage, to my one rep max was. So, really, intensity asks, “How heavy?”

So, we can modify how heavy it is, we can modify how much volume you do, and we can modify your frequency, how often you do it.

DUP, Daily Undulating Periodization is a program that’s very high-frequency, relatively moderate intensity, or starts at kind of moderate intensity and works heavy over the course of the program, and the volume is just moderate every day. But, when you consider the amount of frequency that you’re doing, it’s a lot. And, so, I’ll break it down. It’s real simple.

If we look at the four main lifts that we used for you, which is the squat, the deadlift, the bench press, and the press, I essentially had you doing all four of those lifts three times a week. You were squatting three times a week, you were deadlifting three times a week, you were benching three times a week, and you were pressing at least twice a week. That’s because at the time we were trying to drive up your bench press.

And, what we’ll do, the way we break each one of those down is one day you’ll do those very heavy for low reps. So your heavy day is what we call power. So, you might do squat power work, and that’s things like eight sets of two, six sets of one, five sets of one. We’ve got your strength work, which for squat would be, like, three sets of five, three sets of six, somewhere in that ball park. Then we have your hypertrophy work, so that for squat, and it could be a variation of the squat or maybe even it’s a leg press, or front squat, or whatever. And, that would be things like two sets of eight, three sets of eight. So, we’re going to utilize different rep ranges to get different adaptations throughout the system.

Now, to answer your question about is it intermediate or is it advanced? It’s kind of between. It’s late intermediate, early advanced programming. Because, the program takes about 12 weeks to complete, it’s kind of a long three month program, which would make it feel like an advanced program, but really what we’re doing in DUP is we’re actually bringing up all facets of physical attributes that we want to bring up in the gym at the same time. So, we’re actually trying to increase strength, and power, and hypertrophy with all these different rep ranges at the same time. And, that can be done as a late intermediate.

But, when someone is a world champion power lifter, it would be very hard for them to do frequency that’s that high. And, even for you, as we got towards the end of the program, the amount of fatigue you built up on DUP was a lot. And, we had to start backing off. Okay, let’s get rid of the deadlift hypertrophy this week. Let’s back off your squat strength, instead of three sets let’s do two sets, to just manage that fatigue to make sure you can recover and adapt.

Brett McKay: And, this is where a coach would come in handy, because if I were to try and do this by myself I’d have no clue what I was doing. Like, I would just be trying to either do too much or do too little. So, a coach is sort of there to let you know. Try to aim you for the sweet spot.

Matt Reynolds: Exactly. One of the things that we use, a lot of coaches use, is a concept called RPE, or Ratings of Perceived Exertion. And, what that is, basically, so I ask you every day, “Brett, how hard was it? On a scale of one to ten.” You can look these up, I won’t go through the details. But on a scale of one to ten how hard was it? One, being ridiculously easy, like I’m sleeping in my bed easy, and ten was I either missed it or is the absolute worst thing I’ve ever done, I wanted to die. I potentially pooped my pants in the middle of it. That’s RPE 10, that’s the scale.

And, I use that not to program, so some coaches actually use RPE to program. I use RPE as a communication tool between my client and myself to make sure we’re on the same page. So, you do a set of squats, let’s say you do a set of five, and you do your set of five at 385, which would be a heavy, heavy set of five for you. And, you come back and say, “That was an RPE 10.”

And, I watch the video and watch the bar speed of your squat, and I say, “Actually, Brett, it wasn’t an RPE 10. It was an RPE 9. Or RPE 8 and a half.” It’s my way of communicating with them. It actually, theoretically could’ve been harder.

Or, I have clients do the opposite and they undershoot it every time, “It’s an RPE 7 and a half or 8.”

And, I go, “No, no, no. You might’ve had one more rep and it might’ve killed you, so that was and RPE 9.” So, we can use those.

And, again, what we’re looking at there is not the fatigue that is built up on a single workout. This is why a coach is so important because you would go into a workout after having, say, three weeks of loading, heavy fatigue, that you’re continuing… your fatigue is actually building up in your system over the course of not one day, or two days, or five days, but multiple weeks of fatigue, before I allow the fatigue to dissipate.

So, you would go in on a Thursday and you’ve got squat and deadlift, and you already don’t feel very… you’re, like, “Man, I already feel beat up and I’ve got to hit these numbers,” and you’re, like, “Coach, do I?”

And, I go, “Yep, you’ve still got to do it.”

And, then we get to a de-load week where I would actually incorporate an entire week of recovery-based training, and during that week, all of that fatigue would go away and recovery would kick in. And, then you would adapt. So, remember we go back to that stress, recovery, adaptation cycle as not a one day cycle, or a two day cycle for you anymore. It’s multiple weeks at a time. So, it might take three entire weeks to build up your fatigue before I would give you a de-load week and let it dissipate so that you could recover and then hit new numbers.

Brett McKay: I always liked those de-load weeks.

Matt Reynolds: Yeah, everybody loves de-load weeks.

Brett McKay: So, after DUP, why did you decide to transition me from DUP? If I was, you know, having so much progress with it, I made some incredible gains with that. Why did we transition to something else?

Matt Reynolds: Because you signed up for a meet. The best thing anybody can do for their own lifting is sign up for a competition. Or, even if it’s not a barbell lift or something. If you sign up for a triathlon or sign up for a mud run, you’re training gets better that day, because you’re thinking… and, also, rightly so. You’re Brett McKay, and people who know you in the community, and you know, “Man, I don’t want to go and, like, ruin this, and ruin my name and my reputation”, and ultimately probably do care.

But, like it may sit better that when you get to lift in front of other people it makes your training get better.

Brett McKay: Right, performance. Performance helps improve performance.

Matt Reynolds: Absolutely. Right? So, what I did was I put you on an eight week program, after DUP, before your competition. It’s a program that we just call the high-low, and it really stands for it’s a high-intensity, low-volume program. So, you’ve done all of this frequency and volume on DUP, and built up a tremendous amount of work capacity, and then all of a sudden I dropped your volume to the floor and we go really, really heavy. Because, I needed you to get used to heavy weight on your back for squats, heavy weight in your hands for deadlifts, and press. And, we prepared you for the meet which is a day where you’re basically the competition. You had three attempts at your squat, three attempts at press, and three attempts at deadlift, and they take the heaviest one of each and combine it for a total, and that’s how they determine winners, and your totals, and whatnot.

So, I knew that I needed you to get used to, on that Saturday, you were going to have to do three heavy squats, three heavy presses, and three heavy deadlifts in the same day, and that’s difficult. And, you remember it’s a long day. It’s an eight, nine, ten hour day, and a lot of people will do fine through the squats, and then they get to the press and they go, “Oh, man. I’m getting tired”, and by the time they get to the deadlift it’s, like, “I don’t care anymore, I just want the day to be over”, and so a lot of it is mental toughness and the ability to be used to handling heavy weight over, and over, and over again.

So, that’s why I transitioned you out of DUP and into, kind of, a very heavy max effort sort of program.

Brett McKay: So, I was doing things like one heavy rep on shoulder press, and then I would back off with sort of a… I don’t know how much weight, like you backed me off…

Matt Reynolds: So you might drop 10 to 15% and do some drop sets for AMRAPS or a couple different drop sets. And, then we also started to work supplemental lifts. So, we started to look at where you would miss your lifts. For example on the press, we would do things like press starts, where you would take… I only say press for your listeners. We’re talking about, like, a military press, what most of your listeners would think of as a military press. So, you would do a press, and you’re pressing around 200 lbs, at the time, 185, 190, 195, somewhere in there. I would make you put 210, 215 on the bar to get out of the rack and attempt to press it, so that you could get used to handling heavier weight in your hands, and you were used to actually pressing. And, you would press it up and it would stop about your forehead, and you would grind on it for a second or two and it would come back down and rack it.

So, that would work the bottom of the press. And, then, we would also do lifts on a press, where we would put the bar in the squat rack at the safety pins, maybe an inch or two above your head, where it started there, and you would do press lockouts. You would just lock out the press. We also worked the top end of the press. Now, again, this is an advanced or late intermediate sort of thing we would do. I would never do this with a novice. There’s not reason to introduce the concept of a supplemental lift, which is a lift that looks like the main lifts but attacks at just a certain range in the lift. And, so we’d start to do that.

We’d do that with all the different lifts. We’d do things like pause squats, and box squats, and rack pulls, and deficit deadlifts, and things like that, to attack your specific weaknesses, which again is another reason why a cookie cutter program doesn’t work. Because, on a deadlift, some guys have no problem pulling the bar off the ground and then they struggle at the top. And then, some guys are the exact opposite. That’s you, right? You can pull the weight off the ground and then the lockout is slow, so we’ve got to get you better, and better-

Brett McKay: Gotcha. So, now after the competition was over, did the competition, now I’m trying… my goal now is to lose some body fat because I gained a lot during that, because I was eating a ton, wasn’t really doing any cardio during that time, so was just really working on recovery. What sort of programming are we doing now?

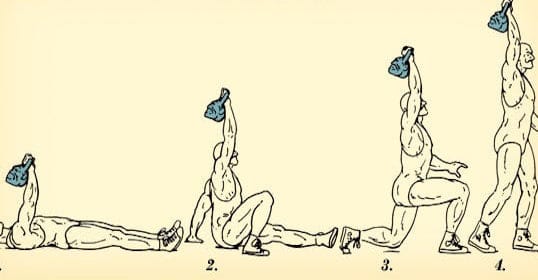

Matt Reynolds: So, really it’s a program that’s just going to allow you to fully recover. So, even though you were peaked for the meet, the meet itself is a tremendously stressful day on you, and it took a week or ten days to even feel back to normal after the meet. And, so we incorporate… right now we’re doing a four week program that’s really a hypertrophy-specific program, higher reps, lighter volume, building up work capacity, doing more circuits. So, you know, I’m not a big fan in kind of traditional cardio, I mean if you like that stuff and you enjoy it, there’s nothing wrong with it. But, as far as accomplishing the goals we’re set out to accomplish, which is to continue to get stronger and to lose some body fat, I’m not ever going to put you on a treadmill for 45 minutes. It just doesn’t work very well.

So, instead, we’re going to do barbell lifts, we’re still going to stick with the main barbell lifts and some dumbbells and kettlebells, and we’re going to do lighter weight stuff for four weeks, and higher reps, and allow you to just recover, and feel better, and full range of motion movements.

And, then we’re going to take your accessory movements and we’re going to put those in a circuit. So, for upper body that might be pull ups, and dips, and curls. And, rather than doing all of your pull ups and move into dips, and then doing all your dips then your curls, we’ll do a set of pull ups, or chin ups, a set of dips, a set of curls, and back to a set of pull ups, or chin ups, dips, curls. And, we’ll do that three or four times through and that’s going to get your heart rate going really good, and that’s going to accomplish both the accessory work that I need to accomplish and conditioning. And, it’s going to do it in a far shorter time because there’s no rest.

Because, ultimately what I’m trying to do here is burn some fat, allow you to recovery, build some muscle, some hypertrophy, and prepare you from a work capacity stand point for your next actual strength program, as we move into… and you know we’ll pick your next meet, and we’ll start to push that direction.

Brett McKay: What do you mean by work capacity? What is that exactly?

Matt Reynolds: Just the amount of work you’re able to do in a given day, week, month, et cetera. So, a lot of power lifters, one of the reason power lifters will get a bad rap, especially power lifters in, say, like the 90s when power lifters all weighed 370 lbs, were big fat guys that nobody wanted to look like. They would get to the point where they just lifted really, really heavy, but they didn’t do a lot of additional work, and so a lot of times they would just go in… there’s a famous power lifter saying from Mark Chalet, he’s famous for basically going in, and his workout, his deadlift workout, would be go in, deadlift for a max, leave. That’s the whole workout. One rep, work up to one rep.

Now, he could deadlift over 800 lbs, so he was really strong, and then he would do squat day and it would be the same thing, work on one squat to one heavy single. Well, how much work capacity does this guy have? I would’ve love to have seen Mark Chalet, and I could be wrong, but I would love to have seen him at a meet that took 12 or 13 hours to get through. That’s a long day for a guy that doesn’t have much work capacity.

So, what I’m trying to do for you is build up the total amount of work you’re able to do and do it in a way that doesn’t super stress you out. So, if I do a lot of volume, which is really what work capacity is, and I do it really heavy, so it’s heavy plus volume, it’s going to beat you up. Your joints, your elbows are going to hurt, your shoulders are going to hurt, and you’re not going to be able to do all of that. Instead, I want to lay the foundation of you being able to do a tremendous amount of total work, and then as I start to transition you into a power program, into a strength sort of program, I’m going to pull some of that volume and let the intensity go up. And, you’ve already built this foundation of, “I can accomplish a lot of work and it doesn’t beat me up anymore.”

So, you can adapt to work capacity. And, so, a lot of our coaches for Barbell Logic Online Coaching that worked with advanced lifters… we’ve got a coach, his name is Austin, he’s a doctor of internal medicine. Super smart guy. The primary metric he uses for his clients, and mostly he works with advanced lifters, is tonnage. Total tonnage. So, you take the amount of weight that you’re going to do, times the reps, times the sets, and you get your total tonnage. And, you can get high tonnage from high volume, or you can get total tonnage from high weight and a little less volume. And, they can both come after the same tonnage. And, we’re just trying to figure out what adaptation are we trying to get right now? Are we trying to build strength, or are we trying to build recovery and work capacity?

For you, right now, we’re trying to build recovery and work capacity.

Brett McKay: But, even with… okay, it’s supposed to be recover and work capacity, like my squat sessions, I hate my squat sessions right now because even though it’s, like, you know I did 420 at the meet, we’re doing things like my last one was 310 lbs. It’s, like, three sets of eight, and I seriously, I wanted to die. And I had-

Matt Reynolds: You’re sore.

Brett McKay: I’m sore, and I had DOMS, you know Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness, for the first time in, like, I think a year. So, what’s going on there? It’s supposed to be recovery but I want, I don’t like it.

Matt Reynolds: So, here’s the difference. The difference is recovery between… we have to pick and choose our battles, which one do we want to beat up. Do we want to beat up muscle and get muscle fatigue, which is what we’re doing right now. And, what’s funny is that you’ve done this now for two weeks, and your second week of squatting three sets of eight you didn’t get DOMS, right? So, it just hit you this first week. Because, DOMS comes in when it’s something you haven’t done before. I don’t know if you’ve even been rollerskating with your kids, have you ever gone rollerskating?

Brett McKay: I’ve been rollerblading.

Matt Reynolds: Okay, never… and you do it rarely I assume, right?

Brett McKay: Right.

Matt Reynolds: So, and when you do, and you do it for awhile, you get real so, like your adductors, your groin gets sore because you’re trying to keep your feet from “whoop” sliding apart because you have wheels on your feet. Why did you get DOMS from rollerblading? Well, because it’s just something you’re not used to.

Why do people get DOMS when they do straight-leg deadlifts? Because they’re not used to stretching their hamstrings. So, you’re not used to doing three sets of eight, that’s a bunch of reps for you after coming out of a high-intensity low-volume. However, the muscular fatigue that you’re receiving from the workout now are not really contributing to systemic fatigue. It’s not fatiguing your, I hate the term, central nervous system, that’s kind of a buzz word we use for people when they… but sometimes it doesn’t beat up your joints, it doesn’t make you feel like you were in a car accident like all these…

It just, in the first week or ten days it creates some muscle soreness just because you’re not used to it, and by three weeks in you’re going to be knocking this stuff out. You’re, like, “This isn’t that hard” and even when you were doing the workouts anyway, you weren’t hitting that first week, you weren’t hitting RPE 9, RPE 10. You weren’t grinding out your squats at three sets of eight. You were, like, “Man, this is a lot of reps, but…”

Brett McKay: I was, like, winded. Like, I was winded. It was conditioning, yeah. Exactly. Yeah, that was not good, but it did get better last… or this week, much better, even though the weight was heavier.

Matt Reynolds: Sure.

Brett McKay: So, we’ll do this for four weeks, what will we move to next?

Matt Reynolds: Well, it depends on prop. So, what we have found with you is that you tend to do better a little heavier weight and little less volume.

Brett McKay: I like less volume.

Matt Reynolds: Yeah, I know, that’s what I figured. So, my plan for you is I have another, I don’t even want to say it, I have another style of DUP, sort of, training, it’s less reps, it’s a lower amount of volume, total volume. It’s a little bit less frequency, but it’s heavier, and I think that will work better for you. And, so, it’s just a variation on the kind of standard DUP. So, to put that in perspective we won’t ever do hypertrophy work and DUP in the eight to twelve rep range.

We’ll do your hypertrophy work in the five to six range, we’ll do your strength work in the three to four range, and then we’ll do lots of singles and doubles for your heavy stuff. And, so, in order to get volume it would be more sets and less reps. So, you think about you could do two sets of eight or you could do eight sets of two, and have the total amount of volume. So, it would be more like eight sets of two for you, six sets of three, rather than two sets of eight.

Because, I think you’ll just recover better that way.

Brett McKay: Okay. And, so I’m at the point now, too, I have to make the decision, do I want to get stronger, and or just kind of maintain.

Matt Reynolds: Correct.

Brett McKay: I think I want to get stronger.

Matt Reynolds: Yeah, and that’s what everybody wants to do.

Brett McKay: I’m young.

Matt Reynolds: It’s addicting.

Brett McKay: Yeah, it’s addicting, it’s enjoyable to be, like, “I deadlifted that much”, it’s fun.

Matt Reynolds: And, you’ve got a coach to watch your form to make sure… you know, one of the reasons is for the last 18 months you haven’t injured yourself. You’ve had almost no injuries. Probably the only time you injured yourself is when you did sprints.

Brett McKay: Yeah, on Thanksgiving Day. So, yeah, okay I was doing some, like, for those of you we are trying to watch this thing called The Strenuous Life and I had to do… there’s a sprinting challenge, there’s like a badge we’ll talk more about it later on, but there’s a badge that requires you to sprint 50 yards, then 100 yards, in a certain amount of time. I hadn’t sprinted in years, and I just went out there, did a little bit of warmup-

Matt Reynolds: Not on your program from me.

Brett McKay: Right, no I was, like, I didn’t even tell Matt I was doing this.

Matt Reynolds: Til after you had hurt yourself.

Brett McKay: And, I jacked up my hamstring. It’s, like, I think it’s I did something to my tendon and it still hurts. It’s still bothering me, I didn’t have that problem until now.

Matt Reynolds: Yeah. As a coach, what I told him was, “Look, man, if…” I am not in the business of dream crushing, so I told Brent, I said, “Had you come to me three weeks ago and said, ‘Hey, I’d like to do some test sprints for this Strenuous Life thing we have coming up’, I’d be, no problem. I can get you there where you can sprint three weeks from now and you’re not going to tear up your hamstring.”

The problem is you went from cold and untrained, and because you were actually testing times, you sprinted at 100% intensity on the very first day you had sprinted in 20 years. So that’s just asking for an injury.

Brett McKay: Right. But, here’s the thing, though. I ran as fast as I did in high school, maybe a little bit faster. It’s barbell training.

Matt Reynolds: Because you’re stronger.

Brett McKay: I’m stronger, right. People, like, yeah… strength leads to power, and power can lead to speed.

Matt Reynolds: Yeah. I was a big 5A high school strength coach for ten years. If I had a sprinter kid come to me and he wanted to get, like, his 40 yard dash time down, or football player sprinter, in the first two weeks I can clean up his form, on his sprint form, where he’s 90% of correct. So that his Charlie Francis sort of stuff, so I’ve got good 90 degree angles at his elbows, his face is relaxed, I can teach him exactly how to set up on the line to make sure he takes the least amount of steps possible for the 40 yard dash. That’s about a two week system.

And, then might actually make his 40 yard dash two tenths of a second faster. And then what? Now I’ve fixed his form, a vertical jump’s the same there, and teach you how to do a vertical jump and clean up your form on a vertical jump. And, maybe get some benefit out of that. I mean I would get some benefit out of that. But, then how do I get any benefit? The only way possible is to make your stronger.

So, here you are, you know a decade later, having not sprinted in many years, at significantly high body weight, I’m assuming. What did you weigh in high school?

Brett McKay: Actually I weighed more in… about the same. Yeah, I was a lineman. I was a fast-

Matt Reynolds: Yeah, you were in good shape. And, so, now you’re years, and years later.

Brett McKay: I’m 35, yes.

Matt Reynolds: And, much stronger, so you’re able to run just as fast as you did in high school, which most 35 year old guys can’t say.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that was enjoyable. But now I’m still struggling with this sort of, I think it’s a tendon in my hamstring that’s jacked up.

Well, Matt, this has been a great conversation. Where can people learn more about you and your work?

Matt Reynolds: Sure. Our website is startingstrengthonlinecoaching.com. You can also find us through Google, it’s pretty easy. We’ve got a great website there. You learn all about Starting Strength online coaches and see the team, and read all about what we do, that we’ve got a great FAQ, and of course anybody has any questions feel free to find me, I’m on the website. Shoot me an email. I do lots of Skype calls and just answering questions for people if they have any questions at all.

Brett McKay: Cool. Matt Reynolds, thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Matt Reynolds: Thanks for having me.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Matt Reynolds, he is my online barbell coach. He’s also the head coach at startingstrengthonlinecoaching.com. You can find out more information about the training program there, and the coaching there. And, also, Matt has offered a exclusive discount for podcast listeners, if you use AOM at checkout you get $50 off your first month. Also make sure to check out our links on the show notes at aom.is/reynolds where you can delve deeper into this topic and find out more.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoy this show and have gotten something out of it over the years I’d really appreciate if you give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. That helps that a lot.

As always, thank you for continued support, and until next time this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.