“In School and Out of School”

From The Successful Man in His Manifold Relations to Life, 1886

By J. Clinton Ransom

Graduation day is a great turning point in the lives of our young people. From childhood they have been at their books and exercises. They have pursued their studies with unwearied diligence, and have gone through many grades of promotion up to the last milepost of their school life. They have been crammed and dosed with language, numbers, science, and literature until they are glad to shake off the incubus of school work and step out into life with some of the rights and privileges of freeborn citizens. Fond parents and admiring friends talk of the finished education, and when the great day of graduation is over, the students of yesterday become the intellectual idlers of tomorrow. The boys go to their vocations, the girls to the idleness of home life or the frivolities of society, but neither of them ever study any more. They have done their books, received their diplomas and are through with their education. Rarely in later life do the “graduates” return to the studies of their youth. Still more rarely do they keep up their studies, after the last bouquets have fallen around the incipient orators of commencement day. There seems to be a surfeit of intellectual work in school and almost an entire absence of it out of school.

This tendency, we think, is all wrong and does much to bring discredit upon our present system of education. At present there is a pressing need of intellectual activity in our American homes. And I mean by this something more than reading novels and newspapers, magazines and continued stories. These may have their place and proper use; but they are very poor pabulum to nourish one’s intellectual life. There is a need of the continuation of the studies of our school-days. If the study of books is beneficial before graduation, it will be equally so afterward. If Political Economy, Botany, and History have a salutary effect upon the mind and life of the student this week, they will have the same effect upon him under the changed conditions of next week or next year. If the work of the senior year has been the most delightful and interesting part of your educational career, might not the same delights be extended indefinitely into the passing years? If the pursuit of knowledge had a charm for you under the guiding inspiration of the grand man whom you respect as teacher, can they be any the less so when you are permitted to wander at will into the rich regions of knowledge beyond you?

Graduation is but an imaginary line that ought to be regarded in no sense as a boundary. It should be only the beginning of a life-time devoted to pleasurable intellectual pursuits. It is hard to maintain an argument for sending a girl or boy to school for a decade of years, with the fact before us that he is justified in shutting his books at graduation and never opening them again. If Latin or Greek is worth studying in school, it is worth while to keep them up after we are done with school. If it is worth while to begin the study of history or literature, it is worth while to pursue them in the leisure hours of life, until we become well versed, in the knowledge and truth which they contain. We think it is unfortunate to make graduation day a “thus far and no farther” of literary culture and attainment.

One of the chief results of a true education is the cultivation of correct intellectual habits. Among these is a habit or taste for reading, that leads one continually to enlarge his fund of knowledge and traverse for himself the most delightful fields of literature. Another habit is that of reflection, by which the mind assimilates its knowledge and grows greater and greater as the years go by. With such habits formed, our education is only begun at graduation day. We hold then only the keys that are to unlock a vast treasure-house stored with the accumulations of ages.

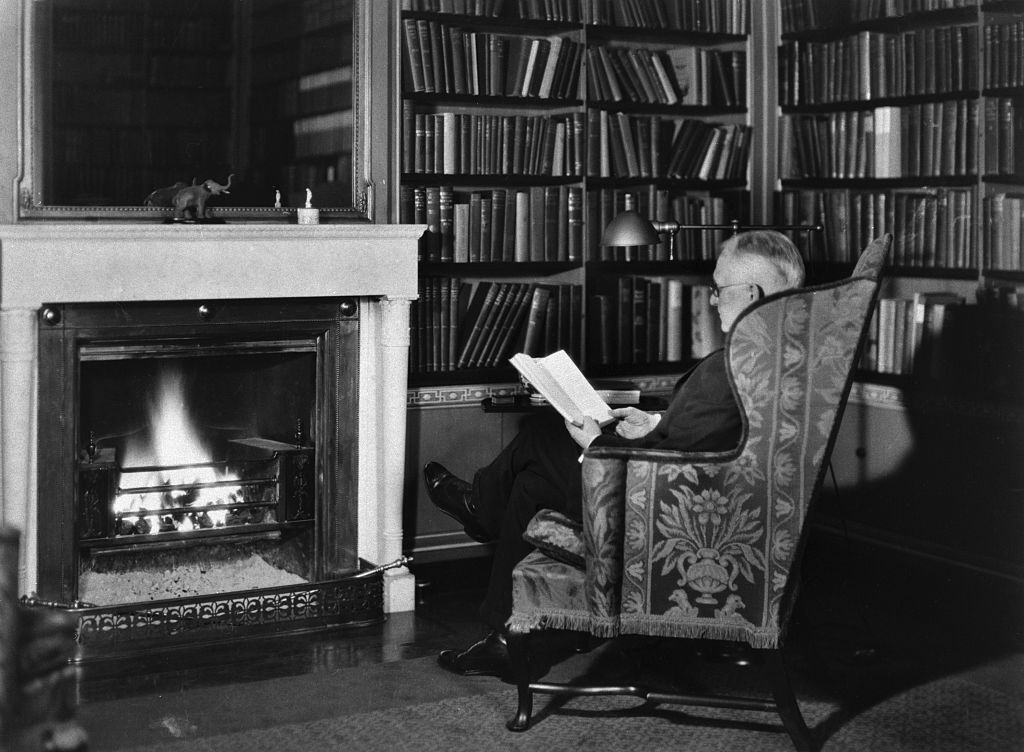

But, says one, our busy lives leave no time for study and reading. Our energies are exhausted and our time consumed in the harrowing duties of daily toil. We have no time for your ideal of continuous study. In reply I have only to point you to some of the world’s great workers to show the utter falsity of such a position. William Cullen Bryant edited a New York daily for many years; but even under the pressure of such great responsibility he managed to write poems and translate the Iliad of Homer into matchless English verse. Mr. Gladstone has been three times Prime Minister of England, and, with the weight of English State upon him, he is one of the most profound Greek scholars of the world, and has published numerous volumes written with most creditable literary skill. Every man wastes more than time enough to make him famous. Half an hour a day saved from the wasted moments of your life and devoted to any field of inquiry will make you master of it in a dozen years. Take the half hour that you wait for breakfast, save an hour in the evening and devote it to well-directed work and you will be astonished at the progress you will make in a single month. The achievements of a well-stocked mind, thoroughly conversant with one or more departments of knowledge, are like a fortune; they are saved and accumulated by slow accretions. Broad intelligence, sound learning, extensive reading, clear thought, lie within the reach of any man who has the will and patience to make the most of his opportunities and devote a leisure hour to reading and study. Such a man is more capable, put him where you will. He will succeed where the empty-headed man that threw his books aside at graduation will fail. The education of the school should thus be followed by the education of mature years.