Habitual watchfulness destroys every frivolity of mind and action. They seldom smile: the expression of their countenances is watchful, solemn, and determined. They ride and walk like men whose breasts have been so long exposed to the bullet and the arrow, that fear finds within them no resting place. —Thomas J. Farnham

The pages of history are filled with masculine archetypes of every sort. Tales of cowboys, explorers, and adventurers take us back to a world that now survives only in history books and the legends fathers pass on to sons. No image of the men of times past stirs a man’s desire for adventure and danger more than that of the mountain man of the early 19th century. Clad in furs and leathers, rifle at his side and knife in his belt, the popular image of the mountain man is the picture of quintessential masculinity, an image which readily symbolizes the virtues of self-reliance, solitude, and bravery. As with all of history’s larger than life characters, the legend of the mountain man has only grown with time. As the decades go by, fact continues to mix with fiction, leading to the popular conceptions of these men that we have today. As we will see however, little embellishment is needed to make the tales of these daring men any more interesting than they already are.

Common Misconceptions

The popular image of the mountain man or trapper is similar to that of Robert Redford’s “Jeremiah Johnson” or Dan Haggerty’s “Grizzly Adams.” While these stereotypical images are rooted in fact, the life of mountain men varied person to person, and there are several notable exceptions to the commonly accepted notion of how mountain men lived. Perhaps the most common misconception about mountain men was that they were loners, wandering the wilderness completely detached from the outside world. Mountain men were not simply wandering the wild in search of adventure and solitude; they were there to make money. The fur trade was booming, and trapping could be a very profitable venture for someone with the proper know-how and equipment. Beaver, one of the most high demand pelts, fetched as much as $6 per pound, a sizeable sum at the time. Trapping was not easy, however, nor was it cheap. The initial investment in gear and supplies was more than most men could part with, leaving trappers of meager means only one option: joining a fur trading company.

Company Men vs Free Trappers

As “company men,” trappers would be outfitted with the gear necessary to properly harvest pelts in exchange for a contractual obligation to sell their harvest only to their company. The equipment provided to them was not free, but was slowly repaid by the trapper through his toils. It was only when a company man had fulfilled his contractual obligations and repaid the costs of his equipment that he had the option to go it alone as a free trapper.

Company men lived a life of contradiction. While the solitude of a life apart from civilization in the wilds of nature was a defining theme of their lifestyle, they also depended on the camaraderie of their fellow company men, whom they were rarely apart from. As a company, trappers could be much more effective than they could as individuals. More importantly, there was safety in numbers. While free trappers enjoyed the independence of working alone and for themselves, there was much more risk inherent to the job.

Yet many trappers of this era, usually gritty, hardened men, often shrugged off these hazards, as the payoff of not having company obligations was substantially higher for the successful trapper. The pelts these men harvested were not sold back to a parent company, but were instead often traded at the next rendezvous, a regular business gathering of trappers and traders. Initially, mountain men transported their furs out of the wilds themselves, but quick thinking traders realized that they could barter better trade deals if they went to the trappers, instead of the trappers coming to them. The mountain man rendezvous quickly became the norm, allowing trappers to forgo the dreaded trip back to civilization to sell off their goods.

A Life of Danger

The life of a mountain man was constantly at risk, with new dangers arising from every direction and at any moment. Every change of season brought with it new dangers, and mountain men had to be prepared for any situation. The spring season was the most profitable, as harvesting was easier and the animals still retained their winter coats. Yet these men plied their trade year round, forced to remain mobile as game moved between hunting grounds. The wilds of the Northwest offered little shelter from the bitter cold of a harsh winter storm, and summer droughts constantly tested their will to survive. Yet it was not only weather that threatened the life of a mountain man. Grizzly bears and rattlesnakes remained a constant threat, as did the indigenous population in the area. As a result of limited supplies that ran out all too quickly, mountain men were forced to trade with local Native American tribes in order to attain necessities. This left the mountain man to weigh the need to approach a tribe with trade goods with the risk that the tribe might be hostile, a common occurrence. With the possibility of death literally around every corner, it becomes clear that the defining characteristic of a mountain man was not solitude, but preparation.

Always Ready

The special thing that Carson had couldn’t be boiled down to any one skill; it was a panoply of talents. He was a fine hunter, an adroit horseman, an excellent shot. He was shrewd as a negotiator. He knew how to select a good campsite and could set it up or strike it in minutes, taking to the trail at lightning speed . . . He knew what to do when a horse foundered. He could dress and cure meat, and he was a fair cook. Out of necessity, he was also a passable gunsmith, blacksmith, liveryman, angler, forager, farrier, wheelwright, mountain climber, and a decent paddler by raft or canoe. As a tracker he was unequalled. He knew from experience how to read the watersheds, where to find grazing grass, what to do when encountering a grizzly. He could locate water in the driest arroyo and strain it into potability. In a crisis he knew little tricks for staving off thirst — such as opening the fruit of a cactus or clipping a mule’s ear and drinking its blood. He had a landscape painter’s eye and a cautious ear and astute judgment about people and situations. He knew all about hitches and rope knots. He knew how to make a good set of snowshoes. He knew how to tan hides with a glutinous emulsion made from the brains of the animal. He knew how to cache food and hides in the ground to prevent theft and spoilage. He knew how to break a mustang. He knew which species of wood would burn well, and how to split logs on the grain, even when an axe was not handy. —Hampton Sides in Blood and Thunder: An Epic of the American West, speaking about legendary mountain man and adventurer Kit Carson.

If a mountain man was not properly prepared, he was dead. As the above excerpt illustrates, the average trapper had to be more than just skilled in trapping and skinning. He essentially had to be a tradesman of every sort, because he had no town full of vendors, smiths, and other craftsmen to rely on when things went south. A wealth of knowledge in skilled trades and survival tactics was essential, but it was not all a mountain man needed to survive. The proper equipment often meant not only the difference between success and failure, but life and death.

In order to be considered properly outfitted, trappers needed to haul an inventory of weapons including rifles, pistols, knives suited for various purposes, and hatchets for wood harvesting. The weight of these items, along with that of the traps, food, clothing, and other items made necessary a trapper’s most vital piece of equipment: horses and mules. Without these beasts of burden, trappers would never have been able to haul the necessary amenities to stay alive in the wild. Additionally, mountain men needed several critical items on their person at all times, which brings us to a staple of mountain man gear, the possibles bag.

The possibles bag is perhaps most comparable to the bug out bags common among modern day survivalists and other well prepared types. In it, your average trapper would store any small items he may have needed for any possible scenario. While several items were common to all possibles bags, every bag had its own unique contents and character reflective of its owner. Essential contents included black powder and a powder measurer, flint and steel, lead balls and patch, a patch knife, and a skinning knife. Other items might include tools for trap repair, tobacco, sugar, and various other objects intended for trade with native tribes. To be certain, a trapper was not a mountain man without a possibles bag slung over his shoulder.

Be sure to listen to our podcast with Hampton Sides about the epic exploits of Kit Carson:

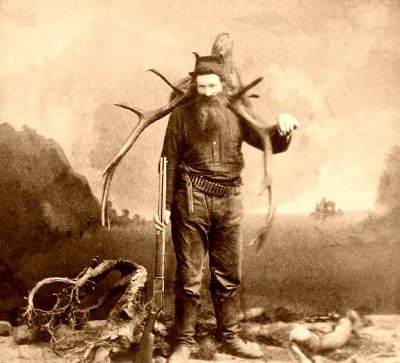

Profile of a Mountain Man: John “Liver-Eating” Johnson

While any true mountain man’s life can be classified as extraordinary, the life of John Johnson was infamous even among such larger than life company. Make no mistake, the actions of Liver-Eating Johnson were not always honorable, as his name may imply, but he was certainly one interesting character (Redford’s Jeremiah Johnson was loosely based on his life). Few confirmed facts are known about Johnson; he was believed to have possibly been a soldier in the Mexican-American War and later during the Civil War, and it is believed he was dismissed from service on the Union side after a physical confrontation with an officer. The legends associated with the man would seem to confirm a violent streak running deep within him, with one particular tale which won him his namesake standing out from the rest.

Following his dismissal from the military, Johnson was rumored to have taken a Native American woman as his bride. This was fairly common practice for mountain men of the time, with the trappers usually leaving their new families at home while they went to harvest pelts. Legend holds that after returning from the wilds, Johnson found the bones of his wife along with the skull of the child she was carrying piled in the doorway of his cabin. Overcome with rage, Johnson immediately fingered a Crow hunting party as the perpetrators of this terrible act, and set out for revenge against the tribe. Over the next twenty years, Johnson killed untold numbers of the Crow tribe in an attempt to satisfy his bloodlust, leaving the bodies maimed and with their livers missing. Rumor held that he ate the liver as an insult to the tribe, a play on the Crow tradition of eating the livers of the animals they hunted in order to ingest the energy and lifeblood of their prey.

Perhaps Johnson’s most notable exploit involved his escape from the brink of death at the hands of the Crow. Johnson, on his way to trade with a friendly tribe, was captured by a hunting party from the Blackfoot tribe. Bound with leather cords and left under the watchful eye of a Blackfoot guard, Johnson knew the inevitable: His reputation, and more notably his vendetta against the Crow, had preceded him, and the Blackfoot planned to sell him to the Crow for a sizable ransom. Faced with certain death at the hands of the Crow, he had only one option . . . escape. Managing to chew through the leather straps binding him, Johnson seized the guard and knocked him unconscious. Once again confirming his brutal nature, he scalped the man and cut off one of his legs, which he then used as nourishment on the 200 plus mile journey to the nearest safe haven, the cabin of a fellow trapper.

Liver-Eating Johnson: Honorable man? Certainly not. Badass? You bet.

___________________

Sources:

Blood and Thunder: An Epic of the American West by Hampton Sides

The West: An Illustrated History by Geoffrey C. Ward