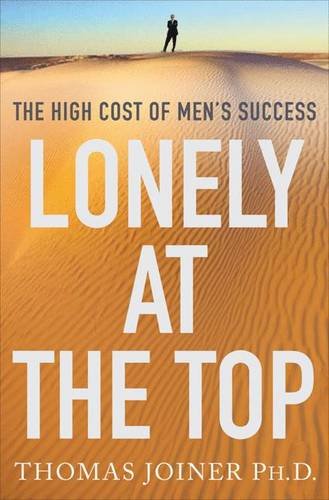

Many men prioritize the pursuit of status, power, and autonomy, which can have its advantages in moving them towards financial security and up society’s ladder. But as my guest lays out in his book, Lonely at the Top: The High Cost of Men’s Success, a focus on work over relationships can also come with significant, even tragic costs.

His name is Thomas Joiner and he’s a clinical psychologist, a professor of psychology, and an investigator with the Military Suicide Research Consortium. Thomas and I begin our conversation with his work around suicide, why men commit suicide at a rate 4X higher than women, and how loneliness is a primary factor in what drives men to take their own lives. From there we talk about the problem of male loneliness in general and how it can begin in a man’s thirties and get worse as he advances through middle age. We unpack the difference between subjective and objective loneliness and how you can feel alone in a crowd, as well as be something Thomas calls “alone but oblivious.” We discuss how everyone is “spoiled” by relationships in their youth, and why men struggle more than women to learn to take the initiative in this regard later in life. We end our discussion with why therapy isn’t the right solution for many men who struggle with depression and loneliness, and how equally effective solutions can be found in simply making more of an effort to balance a focus on work and family with socializing and reaching out to others, and particularly, Thomas argues, in reconnecting with your friends from high school and college.

If reading this in an email, click the title of the post to listen to the show.

Show Highlights

- Men and suicide — unique risk factors and why men have higher rates of death by suicide

- How Dr. Joiner defines loneliness

- What does it mean to be alone but oblivious?

- The value of social redundancy

- The biological detriments of being lonely

- Is the feeling of loneliness rising in America?

- Social media’s double-edged sword

- How are young people spoiled when it comes to relationships?

- Why relationship maintenance is more valuable than new relationships

- Why you should reconnect with friends from high school and college

- Is therapy the right solution for men struggling with loneliness?

- What can men do start investing more in relationships today?

- How does this work in the age of COVID?

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- Inflammation, Saunas, and the New Science of Depression

- The Evolutionary Origins of Depression

- AoM series on male depression

- Finding Connection in a Lonely World

- How exercise can help us find connection

- Understanding the Wonderful, Frustrating Dynamic of Friendship

- Understanding Male Friendships

- How Solitude and Friendship Make You a Better Leader

- The Power of Conversation

- Reclaiming Conversation

- How Face-to-Face Contact Makes You Healthier and Happier

- Fighting FOMO

- Be a Scrooge This Year

Connect With Dr. Joiner

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

If you appreciate the full text transcript, please consider donating to AoM. It will help cover the costs of transcription and allow other to enjoy it. Thank you!

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. Many men prioritize the pursuit of status, power, and autonomy, which can have its advantages in moving towards financial security and up society’s ladder. But as my guest lays out in his book, Lonely at the Top: The High Cost of Men’s Success, a focus on work over relationships can also come with significant, even tragic costs.

His name is Thomas Joiner, and he’s a clinical psychologist, professor of psychology, and an investigator with the Military Suicide Research Consortium. Thomas and I began our conversation with his work around suicide, why men are more likely to die by suicide at a rate four times higher than women, and how loneliness is a primary factor in what drives men to take their own lives. From there, we talk about the problem of male loneliness in general, and how it can begin in a man’s 30s, and get worse as he advances through middle age.

We unpack the difference between subjective and objective loneliness, and how you can feel alone in a crowd, as well as be something Thomas calls “alone but oblivious”. We discuss how everyone is “spoiled” by relationships in their youth, and why men struggle more than women to learn to take the initiative in this regard later in life.

We end our discussion with why therapy isn’t the right solution for many men who struggle with depression and loneliness, and how equally effective solutions can be found in simply making more of an effort to balance a focus on work and family with socializing and reaching out to others, and particularly, Thomas argues, in reconnecting with your friends from high school and college. After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/lonely.

Thomas Joiner, welcome to the show.

Dr. Thomas Joiner: Thank you for having me. Glad to be with you.

Brett McKay: So you are a psychologist who is an expert on suicide, a leading expert on suicide. I’m curious, what led you down the path of exploring why people want to die by suicide, and then also helping people who have suicidal thoughts?

Dr. Thomas Joiner: I guess I’d point to two main drivers of that. One is an intellectual driver. I think it’s a fascinating question, how it is that a creature wired for self-interest and self-preservation, most of whom go to great lengths to enhance themselves and take care of themselves, how can a creature like that come to the point of self-destruction? I think that’s a very profound question, not just about suicidal behavior, but about human nature.

So intellectually, I think it’s profound and fascinating in a window on human nature. As I was starting to delve into it, a personal tragedy occurred, namely the death of my father by suicide. And so quickly, of course, needless to say, it became very personal, very urgent. And it’s largely through, well, both windows I think that I’ve turned to… And part of my work is helping people out of suicidal crises.

I know from my dad’s experience, the misery and the agony, certainly for the person going through the crisis, but also for the family members. And the family members, if there are bereaves like we were, the pain is intense. And so any help, any alleviation of that kind of misery and suffering I think is to the greater human good.

Brett McKay: We’re gonna talk about a book that you wrote called Lonely at the Top, which is, it’s sort of an out… It’s related to your work in suicide, it’s about male loneliness. But before we do, can we talk about, you have this theory, I think it’s called the interpersonal theory of suicide. ‘Cause I think that’ll explain why you think loneliness plays a key role in suicide. Can you walk us through your theory of suicide, and lay a groundwork for what we’ll be talking about here today?

Dr. Thomas Joiner: It starts with one distinction that ends up being kind of an organizing distinction between desire for suicide, or just having ideas about suicide, thoughts about suicide, that kind of thing. That’s a fairly common experience in the general population. But what’s not common at all is taking those thoughts and desires and putting them into action.

It’s certainly very rare for people to put those kind of thoughts into lethal action. Thinking about suicide? Fairly common. Actually dying by suicide? Pretty rare. And that asymmetry always impressed me. It just occurred to me over the years that there must be a variable that explains why it is that most people don’t progress to action, certainly not lethal action, but some people do.

And so that distinction between desire for suicide, and then the ability or the capability to enact it, viewing those as separate processes, I think was very fruitful. Within those two domains of desire and capability, we’ve gotten a little more specific. Desire, we think is made up of two main variables or states of mind. One having to do with the idea that you’re hopelessly cut off and hopelessly alienated from others.

And the second one having to do with the thought that you’re a burden on society, loved ones, family. You might even view yourself as a burden on yourself in the sense that carrying on is just too much. And so in those two states of alienation, loneliness and burdensomeness come together. We think that’s what produces desire.

And then capability is made up of things like fearlessness, fearlessness specifically of physical matters. Things like injury, pain, death itself. Fearlessness of those things we think is a major driver of capability, along with things like pain tolerance, and familiarity, and knowledge having to do with suicidal means.

For instance, if you don’t know anything about firearms, if you don’t know the first thing about how to load one or shoot one, well, then it’s pretty unlikely that you’d die by that method. So practical capability is that. When all those things come together in the same individual, that’s when we predict that these disastrous tragedies happen.

Brett McKay: So along that desire component, it sounds like a big part of the desire is you feel it’s a social alienation, it’s a social problem, a part of it, big part of it.

Dr. Thomas Joiner: Indeed. Yeah, indeed. We’ve named the theory the “interpersonal theory”, because so much of it is social or interpersonal. So much of human nature is social and interpersonal, so most definitely.

Brett McKay: Well, this leads us to Lonely at the Top. And one of the things you highlight in the book is that while men are seen as living at the top of the social totem pole in terms of enjoying money, status, they also are at the top of the totem pole when it comes to the share of death by suicide. Can you highlight, what are the recent statistics about that show the gender breakdown on suicide?

Dr. Thomas Joiner: Well, death by suicide is very male-linked. That’s really clear. The United States is a pretty representative example of the world in general. In the US, for every one woman who dies by suicide, as many as four men do. That’s very skewed towards male-linked mortality or lethality. That’s just for starters.

Men do tend to be less social than women, they tend to be less… Or more lonely. That does seem to be in the cards from early on in the sense that even six-month-old baby boys and baby girls tend to relate to social things differently already at that stage. So these have early roots.

But then over the course of development, certainly into middle adulthood and older adulthood, I think on average… These are just average trends, of course. There are exceptions to the rules, but these are general trends or rules. On average, men become a lot lonelier than women do. Women are better at sustaining cultivating relationships over the course of the lifespan, and men are not.

When you’re 20 or 30, that’s not maybe such a big deal. Maybe relationships are provided to you by college, or school, or work, or what have you. But in the 30s and 40s and 50s and beyond, cultivation and nurturance of these relationships is key. And men by and large aren’t great at that, and it’s very much to their detriment.

Brett McKay: Well, that’s probably that idea that as you get older… People have seen those articles that there’s been this uptick in the number of men in America who are dying by suicide, and you’re like, “Oh, they’re probably in their 20s or 30s.” But no, it’s like they’re in their 50s or 60s.

Dr. Thomas Joiner: Right. It’s a very… Suicide is very linear with regard to age. Generally speaking, it’s linear, in that the older you get, the more at risk you get. It certainly occurs in young people, teenagers, people in their 20s. And that’s noteworthy, and it’s tragic, and also it’s on the increase in those age groups.

But nevertheless, the trend still holds that the older you are, the more vulnerable you are. Obviously, that’s true of a lot of things having to do with health. It’s definitely true with regard to suicide, too.

Brett McKay: Well, so let’s… This idea, your idea in the interpersonal theory of suicide, the desire to want to die by suicide is a sense of alienation, social alienation or loneliness. And so this kind of segues nicely into what we’re gonna talk about today, about male loneliness. How do you define… In your work, how do you… What is loneliness? How would you define it?

Dr. Thomas Joiner: I think there are at least two facets that can be useful to draw out, although they’re very related to one another. And it has to do with the difference between an interior experience, what somebody feels like inside, versus what you might call an exterior experience or what things are like objectively.

In other words, there could be a person, for instance, who objectively, in terms of their exterior experience, they have a lot of connections. They have family members around, they have friends, etcetera. But on the inside, on the interior, they feel desperately alienated and lonely nonetheless. The idea I guess I’d put it is that having people around is no guarantee to prevent loneliness. It helps certainly, but it’s no guarantee.

So I think that distinction between subjective and objective experiences of how peopled one’s experiences are. I think that’s a useful distinction. And it solves some mysteries, because you can talk to families of bereaved people who are bereaved by suicide, and they’ll often say things like, “But we were there for him on that very day. How could he have felt lonely?”

And the answer I’m afraid is that there’s a difference between what’s going on on the exterior, and what’s going on in the interior. On the interior, I think people in that situation feel desperately lonely no matter how many people are around.

Brett McKay: Well, I think in the book, you call that, whenever you’re surrounded by people, family, friends, but you still feel lonely, you call that “alone in a crowd”.

Dr. Thomas Joiner: Right. Yeah. And I think it’s a phenomenon that most people are immediately recognized. It’s happened to most if not all of us, that you just… There can be people around, there can be people who really seem together in something, maybe it’s their belief in a religion or in a political idea, and you don’t feel it, and it can be very lonely. Or even though you’re objectively obviously not lonely in a literal sense, because there’s a crowd around you, it can still be quite lonely despite that.

Brett McKay: Why do you think that happens? Why do you think you can be surrounded by people, yet still subjectively feel lonely? When you talk to people, what do you think is going on there?

Dr. Thomas Joiner: It’s a deep question actually. I don’t know the answer to that, if anyone really does to the depths of the question. The main thing that occurs to me is that that interior world, it’s certainly influenced by the exterior world, but it’s got many other internal influences. When things go awry internally, like if somebody’s in the midst of a major depressive episode, that illness can be so powerful that it just un-peoples the interior world, even if the exterior world is full of love and care.

It’s a very puzzling paradox. But the illnesses, like major depressive disorder, can be so powerful that they unpeople the interior world, even of a very peopled person’s experience.

Brett McKay: So that’s one type of loneliness where objectively, you’re not lonely ’cause there’s people around you, but you feel lonely subjectively in the interior. But you also talk about there’s another type of loneliness, and you call this “alone but oblivious”. So these are… And this happens oftentimes with men.

Men who they don’t have a lot of people around them, no friends, hardly any other social contacts outside maybe their wife and their kids, and they don’t feel… So objectively, they look lonely, but they don’t feel lonely.

Dr. Thomas Joiner: That’s right. That can be dangerous because it can surprise usually men, but anyone, a person, but usually men. It can surprise them because their obliviousness can lift in their late 50s, 60s or 70s. But by then, a lot of the architecture or the machinery that’s needed to initiate and cultivate and sustain relationships, a lot of that is just atrophied. And so people are left in a pretty tragic dilemma of now recognizing how alone one feels, and being unable or feeling unable to do much about it.

That can especially be the case if someone has invested most of their adulthood not in relationships, but into work. I would be the last to counsel against investment in work, I think it’s crucial and key, but it can be overdone. And if it’s overdone to the exclusion of relationships, once that work starts to end or recede, people can be left in a very painful dilemma, stuck in a very painful dilemma.

A lot of men are stuck that way, and then what’s left is their spouse. And then if something happens to her or if there’s a separation, divorce, that’s a very precarious situation. And it pertains to both sexes, but a little bit moreso than men overall.

Brett McKay: So it sounds like this alone but oblivious, so you’re, subjectively you don’t feel lonely, but objectively you are. You might not have any problems, but whenever they become a problem, they become a problem really fast. Like you kind of delay the problem, and then it just hits you really hard once you suddenly realize, “Oh boy, I am really lonely. This is a problem.”

Dr. Thomas Joiner: Yeah, it’s a brittle state, because the reality is that the person’s relationships are atrophying around them, as is the ability to initiate those relationships in the first place. And then it’s sustainable for a while, even decades via connection to work or to a main relationship like that with a spouse.

But I guess the point that I was trying to drive at in that book, at least one of them, is that to have one connection or even two, to say, work and to a spouse, it’s like being in space. And if you’ve just got one connection and a brittle one at that to the spaceship, if you’re on a space walk, that’s precarious. You need backup, you need redundancy.

And that’s the thing, one thing that women are much better at on average than men, they have that redundancy, they work on building up that redundancy and their connections to life via relationships with family, and friends, and work too, and their spouse too. That multiple connection just builds in safeguards and redundancies that can be life-saving when one of the initial connection frays.

Brett McKay: Well, short of construing the desire to want to die by suicide, this isolation, this alienation, social… This feeling of loneliness, what other bad effects does loneliness have on men?

Dr. Thomas Joiner: It has some of the most profound health effects of anything on men and women too. It’s even… There are studies documenting that the effects of loneliness on physical health and on mortality, those effects for loneliness are even stronger than what they are for things like smoking, or obesity, or other plainly medical or biologically relevant threats.

The idea that I take away from that is that loneliness is a biological threat too, and at least as powerful as something like smoking in terms of rendering people at risk for physical health problems and psychological problems too for sure. So I think one of the arguments that I made in that book, and that many others have made too, is that the toxic effects, that the physical biological toxic effects of loneliness are underestimated. They’re at least as strong as something like smoking, daily, regular, pack-a-day smoking.

Brett McKay: So I think we’ve all read articles in the past, I would say decade, where you’d see things that, like Increasing Loneliness in America. Do you know when they do these studies on loneliness, are they talking about that subjective feeling of loneliness? Are they talking about that objective loneliness?

Dr. Thomas Joiner: I think they’re probably talking about both. I think the point does apply pretty well to both. And that stands to reason, I think, because these two things are correlated with one another. One of my points is that they’re not perfectly correlated with one another, and so people can feel alone in a crowd, or alone but oblivious. But mostly people who are lonely know it and feel it and are by themselves, that’s mostly what happens. And so I think those studies are probably with regard to both.

Many of the measures in the loneliness area, especially the brief ones that can be easily administered to hundreds of thousands of people, they tend to focus a little more on subjective loneliness, how it felt and experienced aloneness, than they do on objective, but I think they’re probably targeting both.

Brett McKay: And what’s your take? What do you think is causing the increase of loneliness in America and other Western countries?

Dr. Thomas Joiner: It’s a complicated question. I’m not really one to castigate something like social media use. I have colleagues who do and others who don’t. It’s actually an interesting subject of controversy, but I just see it as a two-edged thing, social media, that is, where I think it can be alienating. I think I can pull people into screens and away from actual relationships. Including relationships, by the way, with the world around like nature and exercise and sunlight and things like that.

But on the other hand, I think it can be good. I think it can bring people together, social media. I think it really does connect people socially. So I just think it’s a little bit of a draw in terms of its negative and positive consequences. That may be a small contributor to increases in loneliness. You can make the same argument about technology in general, is that it’s got a lot to it that’s positive and even connecting, but it can be alienating. I think that’s fairly part of it.

In the United States, the opioid epidemic is relevant. I think that lifestyle alienates people. I think we have a culture in the US of rugged individualism. I think there’s a whole lot to admire about that, and I think there’s a dark side. And that dark side is always there, and it ebbs and flows depending on what’s going on with the rest of the culture.

So those are some of my thoughts about it. Economic factors are certainly relevant, but those have gone up and down. I don’t see those as a clear driver. Fragmentation processes of communities, neighborhoods, families, that’s certainly a relevant factor too.

Brett McKay: So yeah, complex. A lot of factors going on here. But in the book, you highlight a few theories or ideas of what you think is contributing to male loneliness, particularly that loneliness that happens to men when they get to their 50s or 60s, where we see that increase in death by suicide, ’cause they could get so lonely. And the first idea you have is that male loneliness is caused by men being spoiled when it comes to relationships. What do you mean by that?

Dr. Thomas Joiner: I think the way the society is structured, and rightly so actually, is that young people in general, tend to be spoiled about relationships, in the sense that you can be passive as a young child, an infant certainly, but as a very young child, and then into adolescence, you can be a pretty passive and yet relationships for… Or sorry. Opportunities for relationships happen anyway.

They’re just kind of provided for you via family reaching out, being very active via school and related groups of people, just being there for kids. Obviously, there are some kids who are exceptions, but generally speaking, that’s true. And then into adolescence, whether it’s a work force or something like a university setting, or college setting or community college setting, same processes.

And then that serving up of relationship starts to go away, on average into the 20s and 30s. And it’s at that point that an active stance towards really reaching out for new relationships and reaching back to sustain old relationships, that becomes crucial. And I just think men more than women are spoiled out of doing that, and they can cruise on it and coast on it for a while, but often it catches up with them in time, and in time ends up often being in the 60s and 70s.

Brett McKay: Alright. So men are spoilt, so everyone’s spoilt. Men and women are equally spoiled. You make this point, if you look at kids, young kids in their seven or eight or nine, boys and girls, they have the same number of friends basically. Both of them are great ’cause they’re in school, they got their friends at school, they got sports.

But if you ask those same boys and girls, when they’re 60 or 70, how many friends you have, there’s a disparity. The women are gonna have more friends, but the men aren’t gonna have as many friends because they stop taking… Well, they took relationships for granted. They just thought they just happened, but they reached a certain point in their life where you had to actually be active about your friendships.

Dr. Thomas Joiner: Exactly. And making new ones. I think being active about relationships can take at least two forms, and one is being open and even eager for new relationships, new friendships, and that requires effort. For instance, on university campus, the way that the incentive structure is these days, in most US universities at any rate, one is encouraged to drill down into sub-sub-specialties. And so you’re not incentivized to relate to people on other quarters of the campus.

I’m in a Department of Psychology, we’re not incentivized to show up to functions of the Departments of English or Religion or Biology or Physics. I’ve done that. I’ve taken active steps to do that, and it’s been very rewarding because intellectually, you occasionally pick up a new idea, but socially, you’re just introduced to a whole new group of people, people who are really a delight. Whom you’d never have met if you just stayed on autopilot and did the passive thing.

So that’s one aspect of being open to friendships is openness to new relationships, but arguably more important is the reaching back to re-kindle or to maintain relationships that were really important back in the day. I think there’s a special power to the friendships that are forged in the age between the ages of, say, 10 and 20.

A lot of people can think of people who were really important to them back then, I mean crucially important to them back then, whom they haven’t reached out to in decades. Years at least, sometimes decades. And it’s not that hard to just pick up a the phone, especially these days with the internet, and reconnect with those people.

And the other thing I can say from personal experience is when you do that, I guess some people fear that it’ll be awkward, it won’t be the same like it was, it’ll be just be a waste of time. My experience has been completely contrary, where sometimes over the course of 30 years, with no contact over 30 years, immediately one just clicks back into that same rhythm or that same familiarity, that same comfort.

I think there’s a special power to friendships like that, so that’s the other form of relationship maintenance, I guess would be the word, that I think is arguably even more important than being open to new relationships.

Brett McKay: I actually had that experience of reconnecting with an old friend. A few weeks ago, out of the blue, my old college roommate texted me, he’s like, Is this Brett’s phone number still? And I was, “Oh, hey. It’s great to hear from you.” And then I was like, “Let’s talk.” And we got on the phone and we talked for about 45 minutes, and it was, I felt great.

I felt great for a few days after that, just having that conversation and reconnecting with him. I hadn’t talked to him in 15, 20 years. It’s been a long time.

Dr. Thomas Joiner: It’s remarkable. I’ve had many times myself, similar experiences also, I’ve just made a real point, this is not for everybody, of course, but I’ve just made a real point of showing up to high school and college reunions. And that’s where you really see it, is there are people there who you haven’t seen in 20 years, 25 years and 30 years. I’ve just been amazed at how it doesn’t matter, it just you just pick up that same easy rhythm and rapport, just like when you’re 15.

It’s very pleasant and fun, and it does improve your mood. And then if you do that serially and maintain that across the different relationships, I think it maintains mood. You said it maintained your mood, for that one example, for days. But I think if you do this serially, you start to multiply that and it becomes. It maintains mood for weeks and months and years. So I heartily recommend it. I can’t think of one example where I’ve reached out and it backfired.

I guess these days, things are fraught with politics and such, but I would counsel putting all that aside and just focusing on the friendship and the comfort and the easy rhythm and familiarity of the friendship back in the day, and trusting that at least some of that will revive if you just take the effort to reach out.

Brett McKay: Well, one of the reasons you hypothesize that women tend to be better than men at maintaining relationships in adulthood, is that men, if you’re speaking to generalities, tend to take a more instrumental approach to the relationships.

Dr. Thomas Joiner: I think that’s fair, and it’s also fair to continually emphasize that generalizations are always subject to criticism. That’s fair. But the data also… What’s also fair is to face the objective data, and they’re very clear that, yeah, these are true trends where men tend to be more like that than women. To their benefit sometimes, being instrumental pays off, can pay off.

I actually encourage it. I think it’s a good thing, I just don’t think it’s a good thing in extreme excess to the degree that you neglect other things like the relational aspect of humans. That’s dangerous, and that’s gonna catch up with you sooner or later in my view.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that instrumental approach to life. That’s what allows men to get a good job, buy a home, establish themselves. You have to… You’re just thinking about what you gotta do to get those things. And those are all good things, but I think the case you made is that you have to temper that.

You can’t just make your whole pursuit in life, money and status and work, ’cause if you do, you’re gonna end up alone in the… Have that alone in the crowd, or that alone but oblivious thing going on.

Dr. Thomas Joiner: That’s right. Moreover, if you do overdo it with the instrumental kind of approach, in the best case, you’ll be financially successful or professionally successful and lonely. But that’s the best case, and that’s kind of rare overall, especially if you’re talking about very, very high levels of achievement or of wealth.

What’s a little more common is for it not to work out on the instrumental side and you’re lonely there too. That’s a witches brew, that’s disastrous for health hell in the last half of life. Men are just making that bet more than women, and it’s a risky bet, and there’s no need for it, especially when our natures are such that it’s just natural to relate to one another. It’s an unsafe, risky, unnecessary bet in my view, and men make it more frequently than women. Women make it too, but men, men definitely make it more frequently.

Brett McKay: I was thinking about that idea of instrumentality coming at the expense of relations. We’re coming up on Christmas, made me think of Scrooge, Ebenezer Scrooge. I think he’s like the epitome of that. He just focused on money, money, money, and then he sees his future self and no one comes to the funeral and people were just stealing the bed curtains from his bed. [chuckle] And he had no friends at the end. Of course, he changes himself at the end, he realized, “Oh, relationships are important too.”

Dr. Thomas Joiner: Yeah. That’s a good image or a good symbol of these processes, ’cause… Yeah, that’s right. The other thing that I might add here is that it can seem a little bit pollyannaish or a clichéd or naive maybe to say, “Don’t worry about work or achievement or money. Don’t worry about that. Relationships are everything.” That’s not really what I’m saying though. What I’m saying is, go ahead and work 10 hours a day and keep that up. But as you do that, you can weave in relationships.

You can work a 10-hour day and then go home and text your best friend from college or high school. That takes one minute, if that. So I’m just talking about little doses of this. At a minimum, it’s not hard to do. It’s not naive or clichéd or pollyannaish. It’s balanced.

And that’s what I’m going for, is I think things get out of balance for some people who end up in crisis or even in the disastrous situation of suicide death, very out of balance. And to get that balance back is not all that hard. It doesn’t have to be 50-50. It just can’t be 100-0.

Brett McKay: Well, another type of loneliness or cause of loneliness that could happen to some men is men who they make their focus money and status, climb the corporate ladder, and they find themselves at the top of the ladder, of the pile, the pyramid. And you think, “Oh man,” you look at these people, “Oh man, that guy’s got it all.” He’s got people surrounding him, they wanna… Men wanna be him, women want to be with him. But you ask him, “How you’re feeling?” he’s like, “I feel terrible, I’m completely lonely.”

What’s going on? Have you counseled people like CEOs or anything like that, where they’ve… They’re at the pinnacle of success, but they just feel completely miserable ’cause they’re incredibly lonely?

Dr. Thomas Joiner: Most definitely. Think one of the things that feeds into that is that when you get to those levels of achievement in terms of whatever it may be, creative endeavors or professional achievement or wealth or whatever, you start to elevate yourself out of social circles. There are people who just don’t think they can relate to you because of… You’re just elevated beyond that. That’s a danger of a very high achievement.

But there’s a remedy for that. One is signaling to people that despite the fact of the achievement or the fact of the wealth, it’s just not true. It’s just not true of who you are. I think you can signal that in your demeanor and comportment. But I also think that that’s yet another reason to reach back to the friends in college, ’cause they knew you back then when weren’t whatever, a CEO or a great artist or any of that. They knew you when you were just some guy.

I think that there’s great value in that, underestimated value. I haven’t studied it rigorously, but in talking with my own social circles, I’ve been impressed by how few of the people that I know remain in contact with their best friend from when they were 15, for example. Pretty common not to be in contact with that person.

The idea, I guess, being that you’ve grown apart or grown out of that. I suppose that can happen, but I’ve seen it too many times where despite differences, despite growing in different directions, there’s still that easy, familiar, knowing, understanding, rapport that just kicks right back in. And it’s, I think it can be vital to thriving and flourishing.

Brett McKay: So we’ve talked to some reasons why, what causes male loneliness. Men are spoiled. And by “spoiled” you mean they just, they take relations for granted. They don’t learn how to actively foster or maintain relationships until it’s too late, or they get distracted with good things like work and money and status. Those things can be good, but they focus on that only at the detriment of the relationships.

So when men, once they start experiencing that emotional loneliness, the subjective feeling of loneliness, in your research, how do men typically cope with loneliness? I imagine women probably reach out to people. What do men tend to do?

Dr. Thomas Joiner: It depends on… There’s a healthy reaction and an unhealthy reaction, and unfortunately, men tend towards the unhealthy reactions of turning to alternative sources of seeming support or seeming connection. Things like alcohol, alcohol and drug abuse. Things like sexual contact, absent real relationships. Or sexual contact that damage existing relationships. And any number of other kind of distractions.

That’s how I view all those things is as distractions from what really is our life-blood, and that’s true relationships with people who are part of us, family, friends, friends from back in the day. And so that’s an unhealthy move in response to this growing awareness of loneliness. A good way to use loneliness is just like you use physical pain. Physical pain is signal, “Hey, something’s wrong. Something’s the matter with my knee or my hip,” or whatever the case might be.

And you can take that signal of knee pain or hip pain and try to drink it away, or you can go to the doctor and get it fixed. With loneliness that signal, same thing, you can try to drink it away or what have you, or you can turn to the effort… It’s not that hard of an effort, but it’s an effort to build new relationships and sustain or rekindle old ones.

So I would use it like a pain signal of, “Hey, things are going wrong and I gotta right them,” and there’s a way to right them and it’s not that hard, and that’s the better choice. The other choices just have too many risks to them, and they lead to ruin pretty regularly.

Brett McKay: Yeah, it’s not that hard. I think you mentioned this in the book, oftentimes a response to male loneliness, we think about, “Well, you just need to get these guys into therapy, and they’ll start talking about their emotions and opening up and that will solve it.” You’re kind of dubious about that solution. Why so?

Dr. Thomas Joiner: You’re right, I am skeptical of that. It’s interesting, because I am a therapist and I am a psychologist, and that’s kind of the stuff that we do. I don’t have disrespect for it at all. It actually works really well if the person is ready to take it, and if they’re ready for it, it works great. That kind of stuff.

That’s a problem though, because not everyone is motivated to do it, it doesn’t fit everyone. Men, I think can be, on average, a pretty bad fit for traditional forms of psychotherapy. And so I think we need to be creative to engage in just kinda small behavioral fixes along the lines of what we’ve been discussing. Or at least as powerful as traditional… As trying to convince men to stick with traditional psychotherapy.

That’s not for everybody, and I, unlike most psychologists, I think that’s completely obvious as to why that’s not for everybody. I guess unlike most psychologists, I’m not willing to throw my hands up and say, “Well, we’ll just focus on the ones who are interested in what we do.”

I don’t think that’s good enough, because it leaves out a whole segment of the population who do need help and who we can help with our research and with our work and our clinical techniques. We’ve just gotta be thoughtful about adapting them culturally, so to speak, to the culture or to the mindset of different subgroups in this case men.

Brett McKay: So what are some things… We talked about a few, like things that people who are feeling lonely, they can do, like just reach out, connect to an old friend. But what are some other things that men can do to start reducing loneliness and investing in relationships more? That don’t involve having to go to therapy, if that’s not something they wanna do or feel comfortable with.

Dr. Thomas Joiner: Right, the easiest place to start is just… And we do this within the clinic that I direct here in Tallahassee, Florida, we bargain. We make simple bargains with patients that they’ll just show up to a gathering of some sort, a gathering that they had not planned to show up to, but they bargain that they now will. That’s all they have to start with. All they got to do is show up.

It could be anything, any gathering, it can be at a whatever, a classroom or a museum or something else on campus, or some sort of sporting event, or a community organizing event, religious event, political, it doesn’t matter, just as long as there are people there together. The idea being that there is a natural human tendency to reach out and socialize, and if you put a particular human with other humans in a group, sooner or later, that natural tendency is gonna spark.

However, if you isolate that human from other ones, that won’t spark. So a simple idea is that at least get exposure to other people, so that the chance that that natural tendency will spark is enhanced. If people will agree just to do those kinds of things on a regular basis, that alone goes a long way. It doesn’t immediately cure something like a major depressive disorder or a suicidal crisis.

But what it does start to do is turn the tide over the course of time and repetition to where a bad major depressive, for example, has become less bad, less severe. A suicidal crisis has gone from potentially lethal down to still quite distressed, but now non-lethal, that’s a huge distinction. So I would start there, with just the idea of the basic idea and the simple idea of showing up.

Brett McKay: How do you do that? We’re still in the pandemic here, where a lot of communities are starting to clamp down with stay at home orders and things. How do you do that during a pandemic?

Dr. Thomas Joiner: The fix there is the same fix that we… Most all of us have seen with regard to work and meetings and things like that, and it’s gotta be at a distance or remote or virtual. In my own view, that’s just not the same, quite the same dose as in-person gatherings, but that’s where we are for the foreseeable X number of months. Until then you take what is available, and it would be virtual kinds of analogs of the showing up.

I’ve shown up myself to colloquia, seminars and the like around the campus on FSU, but it’s been from my home via Zoom and similar kinds of technologies. It’s a peopled experience, but it’s not quite the same, but it’s better than nothing. And I’ve also done some distanced sort of socializing, small groups outside, sitting six or seven feet apart, that kind of thing. We’re coping temporarily, but the same principles apply, of showing up and reaching out a little bit.

Again, it doesn’t have to be that big of an effort but just the start of showing up and getting those natural processes of connection sparked. I think that’s… It’s a starting point, let’s put it that way. At any rate, at least it’s an initial step.

Brett McKay: We got this membership program called the Strenuous Life, and members can get together in their geographic areas for meet-ups. And it’s been interesting to see what people do during the pandemic. They’ve done some virtual stuff, but an activity just doing stuff outside in nature, where it’s relatively COVID-safe, you can social distance and you’re outside.

So rucking, so basically hiking with a backpack, that’s been a popular activity. Or just doing stuff… And I think you even write this in your book, nature can be of a part of the process of alleviating or combating loneliness in men.

Dr. Thomas Joiner: Absolutely. I’m very, very drawn to ancestral evolutionary explanations of why our nature is what it is. Human nature has these features because of our evolutionary ancestral past. And one was small group, deep dependence for survival itself, dependence on each other. Another was our close intuitive, regular daily relationship with nature, with plants, with trees, with animals, with all elements of nature, with water, swimming in water, fishing in it, boating in it, all of these things.

In a modern technological world, those things can recede, and I don’t think that’s in our natures. Technology, I’m not a anti-technology kind of person, on the contrary, if anything. But again, it’s a similar theme of everything in moderation, and technology in moderation, the neglect of nature needs to be moderated too. It’s essential to who we were, and therefore, I think essential to who we are.

Brett McKay: Well, Thomas, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about your work? Is there some place people can go?

Dr. Thomas Joiner: Probably the main site would be via the Department of Psychology at Florida State University. If you just Google my name and FSU, I think that’ll get you immediately there. The books I’ve written on topics like loneliness, explaining why people die by suicide, things like that, are available too. At all the usual places, Amazon, etcetera.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well, Tomas Joiner, thanks for your time, it’s been a pleasure.

Dr. Thomas Joiner: My pleasure, thank you for having me.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Thomas Joiner, he’s the author of the book, Lonely at the Top. It’s available on Amazon.com. Check out our show notes at AOM.is/lonely, where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AoM podcast. Check out our website at artofmanliness.com where you can find our podcast archive, as well as thousands of articles we’ve written over the years about pretty much anything you can think of. And if you’d like to enjoy ad-free episodes of the AoM podcast, you can do so on Stitcher Premium.

Head over to stitcherpremium.com, sign up, use code MANLINESS at checkout for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the Stitcher app on Android or iOS and you can start enjoying ad-free episodes of the AoM podcast. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate it if you take one minute to give us a review on Apple Podcasts or Stitcher. It helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you.

Please consider sharing the show with a friend or a family member who you would think would get something out of it. As always, thank for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding you all to not only listen to the AoM podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.

Tags: Friendship